Neil Sheehan, the legendary reporter who obtained the Pentagon Papers for the @nytimes, died Thursday. This WaPo obituary has a great photo of Sheehan, then of UPI, chatting with other reporters in Vietnam in the 1960s. https://twitter.com/washingtonpost/status/1347293454808862721

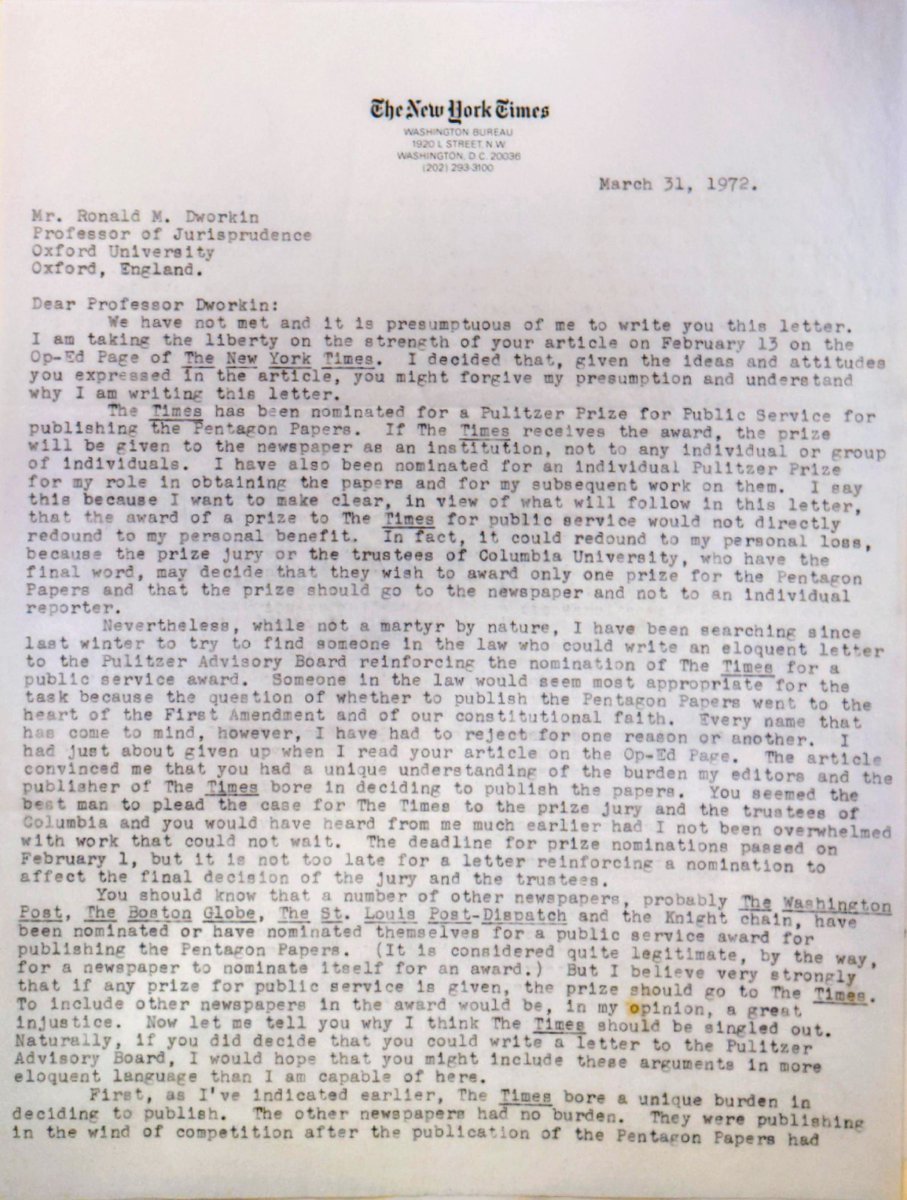

There is one story you won’t find in the obituaries. In March 1972, Sheehan wrote, out of the blue, to Ronald Dworkin. Dworkin had written an op-ed in the @nytimes which had caught Sheehan’s attention.

In his piece, Dworkin argued against the idea that the press must exercise its freedom with self-restraint. The idea, said Dworkin, is based on a false analogy.

“Newsmen exercise their right to speak not as individual citizens, who may give up their rights in what they think is a good cause, but as trustees for the rest of us”.

Editors have no business deciding what to keep out of view. It’s worse when an editor rather than a government agent suppresses information, for the government can be exposed and challenged in court.

Dworkin’s claims were close to Sheehan’s heart. Sheehan had been looking for someone ‘in the law’ to write to the Pulitzer Advisory Board in support of the @nytimes’ candidacy for the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service.

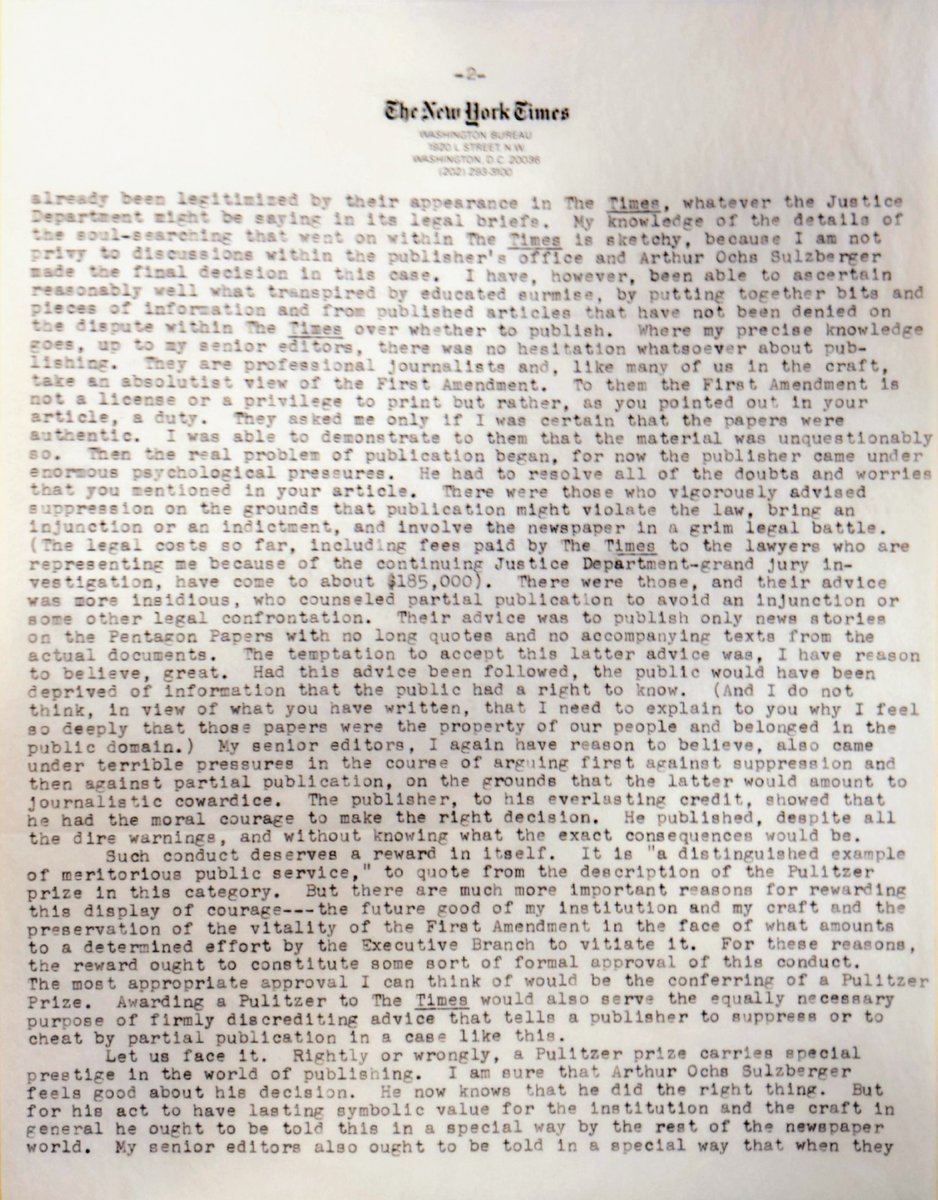

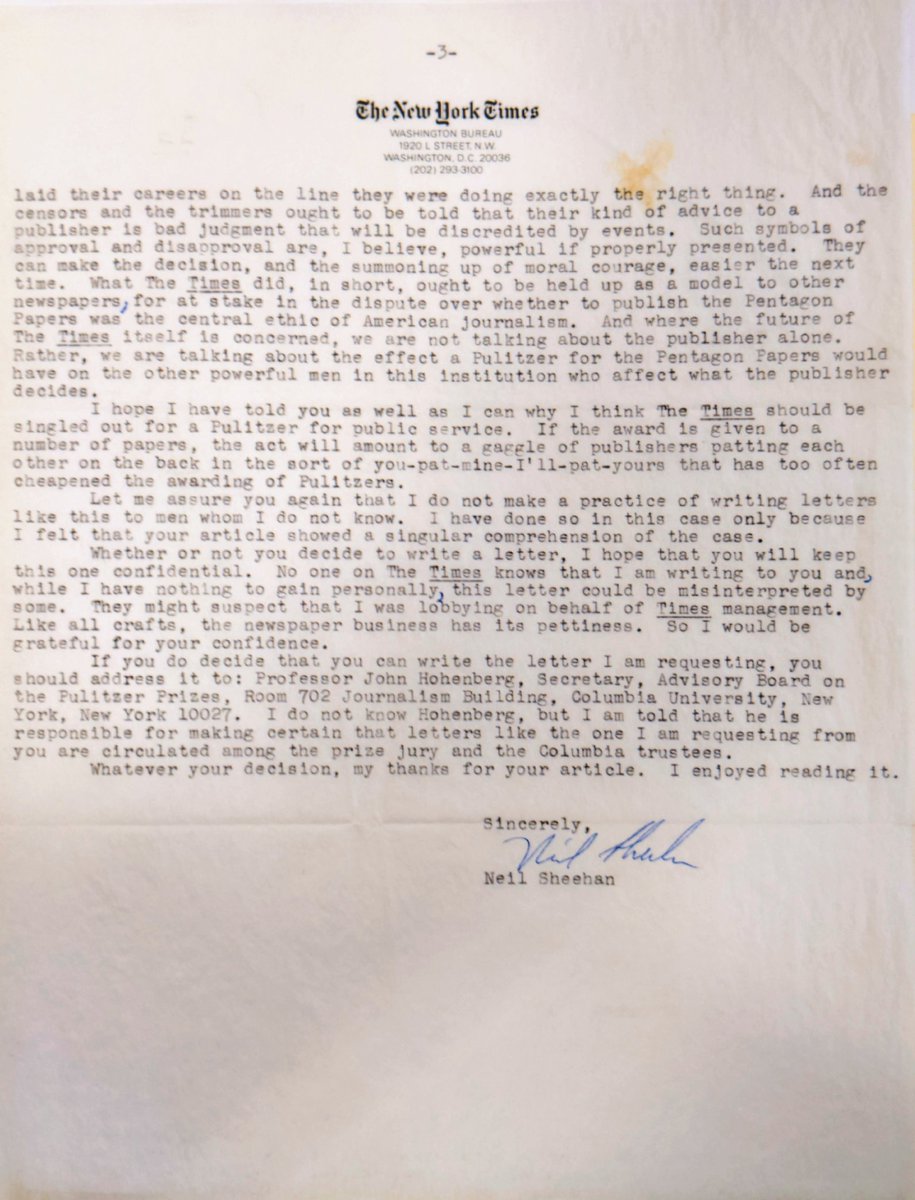

Sheehan knew how to pitch. Also he could write. In three closely typed pages he makes his case forcefully and elegantly. He stresses that the Times as an institution should get the prize and is adamant that the prize should not be shared but should go to the Times, alone.

Its publisher and editors bore a unique burden in deciding to publish in the face of enormous pressure to suppress or minimize, and only by singling out the Times would the prize operate as it should.

By awarding the prize to the Times, the rest of the newspaper world would be standing with the Times’ publishers and editors against those counseling suppression and holding up the decision not to suppress as a model for the profession.

It was central to Sheehan’s case that obtaining the Papers was not theft nor was publishing them a violation of a duty of secrecy. Sheehan’s thesis had been that the Papers belonged to the American people, and they had a right to see them.

Dworkin’s idea of the press as trustees suggested that Dworkin would be sympathetic: “I do not think … that I need to explain to you why I feel so deeply that those papers were the property of our people and belonged in the public domain”.

We find this thought again in Janny Scott’s account of how Sheehan came to obtain the papers, which appeared in the @nytimes on the day of his death. As Sheehan told the story, Dan Elsberg suggested that Sheehan stole the papers (from Elsberg), like Elsberg did (from Rand).

‘“No, Dan, I didn’t steal it,” Mr. Sheehan said he had answered. “And neither did you. Those papers are the property of the people of the United States. They paid for them with their national treasure and the blood of their sons, and they have a right to it.”’

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter