I've said it before, and will say it again. This is one to watch.

New pipeline proposals may get the bulk of public attention, but this case has very big potential impacts on Western Canadian oil markets.

Some thoughts... https://financialpost.com/commodities/producers-slam-enbridges-efforts-to-set-mainline-contracts-before-competitors-extensions-completed

New pipeline proposals may get the bulk of public attention, but this case has very big potential impacts on Western Canadian oil markets.

Some thoughts... https://financialpost.com/commodities/producers-slam-enbridges-efforts-to-set-mainline-contracts-before-competitors-extensions-completed

I don't yet have a conclusion I'm willing to share on whether Enbridge's proposal for long term contracting is "good," "bad" or "ugly."

But there is lots to unpack here.

But there is lots to unpack here.

It is worth mentioning/reminding that the core reason we regulate tolls in the pipeline services sector is to address the monopoly/holdup problem inherent in the industry.

Each pipeline route is, almost by definition, a natural monopoly (huge economies of scale). There might be some competition between lines, but if the NEB has exercised appropriate due diligence it should not have approved pipelines that are close competitors.

That is, pipe should either serve different routes/markets, or (if there are two lines serving the same market) then the additional pipe should only have been approved if there is sufficient demand for it.

It's a bit of a foreign concept right now, but "too many" pipelines is bad because of the "business stealing effect" (Mankiw and Whinston 1986).

Now, back to Enbridge.

Now, back to Enbridge.

In many ways, Enbridge's application for long term contracting is the culmination of a process that started in the early to mid 2000s.

From the 1950s up to 1995 or so the NEB regulated all common carrier pipe using a cost based "Rate of Return" model.

From the 1950s up to 1995 or so the NEB regulated all common carrier pipe using a cost based "Rate of Return" model.

Under this model, the NEB would set tolls (usually annually) to deliver a fixed ROR. Evidence on the pipeline's costs and it's underlying cost of capital was gathered and presented at annual toll hearings.

In the late 90's, (arguably beginning with the approval of an "incentive based" regulatory approach for the Westcoast system), the NEB began to allow departures from traditional ROR and the annual rate hearings. Thus began the age of "Negotiated Settlements."

The idea was to organize the shippers as a negotiating block and to have them directly negotiate tolls with the pipeline, absent direct oversight from the NEB.

The NEB would review "process," and would monitor for complaints, but would not be involved in negotiations.

The NEB would review "process," and would monitor for complaints, but would not be involved in negotiations.

Toll applications based on settlements would either be accepted in their entirety or the NEB would reject (usually based on some complaint or failure to negotiate an uncontested settlement) and would default to old style ROR.

In the early days, it was not uncommon for the settlement process to break down and for a pipe to move back to ROR for a year or two before getting another settlement together.

Some shippers complained, indicating to the NEB that often a majority of shippers agreed to the terms of a settlement, but that a minority could contest it and get the NEB to revert to ROR.

To solve this, the NEB began allowing for "contested settlements" when appropriate.

To solve this, the NEB began allowing for "contested settlements" when appropriate.

The result was that Settlements basically completely took over from traditional (rate hearing) based ROR.

What had been intended as a bilateral monopsony model now (arguably) allocates more bargaining power to the pipeline, except where there is competition between pipelines (which, discussed above, is something the NEB is supposed to mitigate through the facilities approval process)

These negotiated settlements began to branch into multi-year and (for some pipelines) much longer term agreements, to the point where tolling methodologies for new lines/expansions are entirely based on long term (decade or more) contracts.

In some ways, this may match the production profile of shippers better. Long term contracting is a risk allocation mechanism and (depending on the terms of the settlement) can act like an RPI-X model (which, it is argued, offers better incentives for cost reductions etc.).

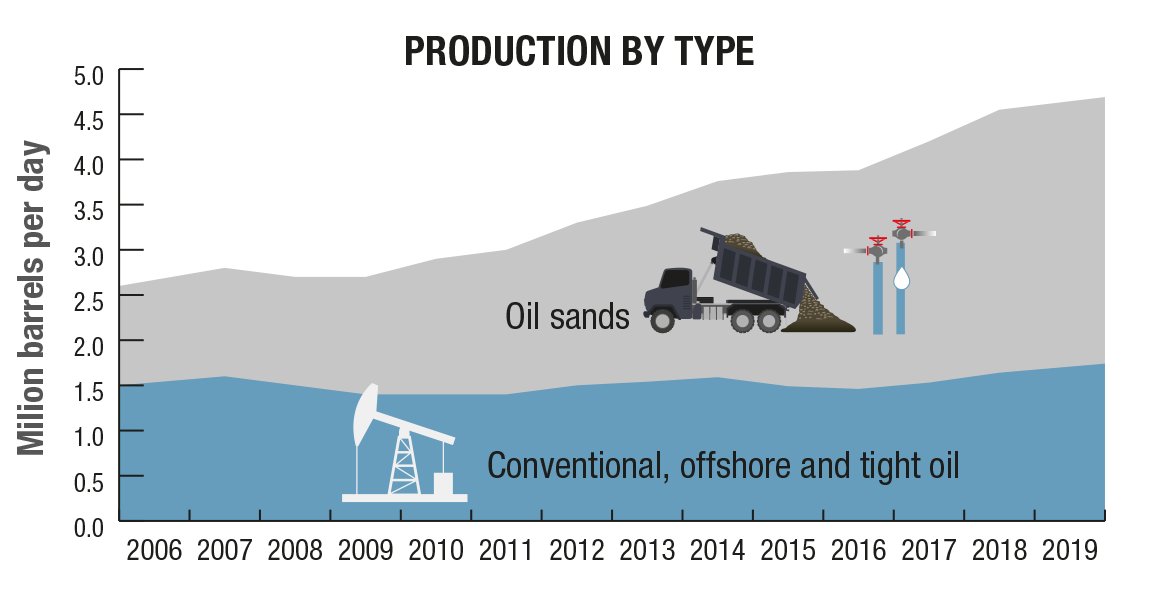

From a risk allocation perspective: Oil sands production makes up a way larger chunk of total Alberta production now than it did even 15 years ago.

(source of graph is: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/science-data/data-analysis/energy-data-analysis/energy-facts/crude-oil-facts/20064 )

(source of graph is: https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/science-data/data-analysis/energy-data-analysis/energy-facts/crude-oil-facts/20064 )

This is relevant, because there is less variance in production from oil sands (very shallow decline curves almost flat over much of the project's multi-decade lifetime) compared to conventional where you have to keep exploring and punching holes.

So, longer term contracts *might* fit the needs of some shippers better.

But, longer term contracts also mean that the various risks are distributed differently.

But, longer term contracts also mean that the various risks are distributed differently.

Market demand risk shifts from the pipeline operator onto the shippers.

The pipeline's risk of input cost shocks shifts from the shipper onto the pipeline.

The pipeline's risk of input cost shocks shifts from the shipper onto the pipeline.

Shippers also lose some option value. Pipe capacity based on long term contracts becomes a sunk cost which limits the ability of shippers to profitably take advantage of inter-regional arbitrage opportunities.

So, lots to unpack here.

It will be very interesting to watch the evidence submitted to the CER by all parties involved.

It will be very interesting to watch the evidence submitted to the CER by all parties involved.

If you're interested in the use of Negotiated Settlements in the pipeline services market, why not* buy my book:

https://www.amazon.ca/Negotiated-Settlements-Pipeline-Services-Market/dp/3846525170

*DO NOT BUY MY BOOK, IT IS GROSSLY OVERPRICED.

https://www.amazon.ca/Negotiated-Settlements-Pipeline-Services-Market/dp/3846525170

*DO NOT BUY MY BOOK, IT IS GROSSLY OVERPRICED.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter