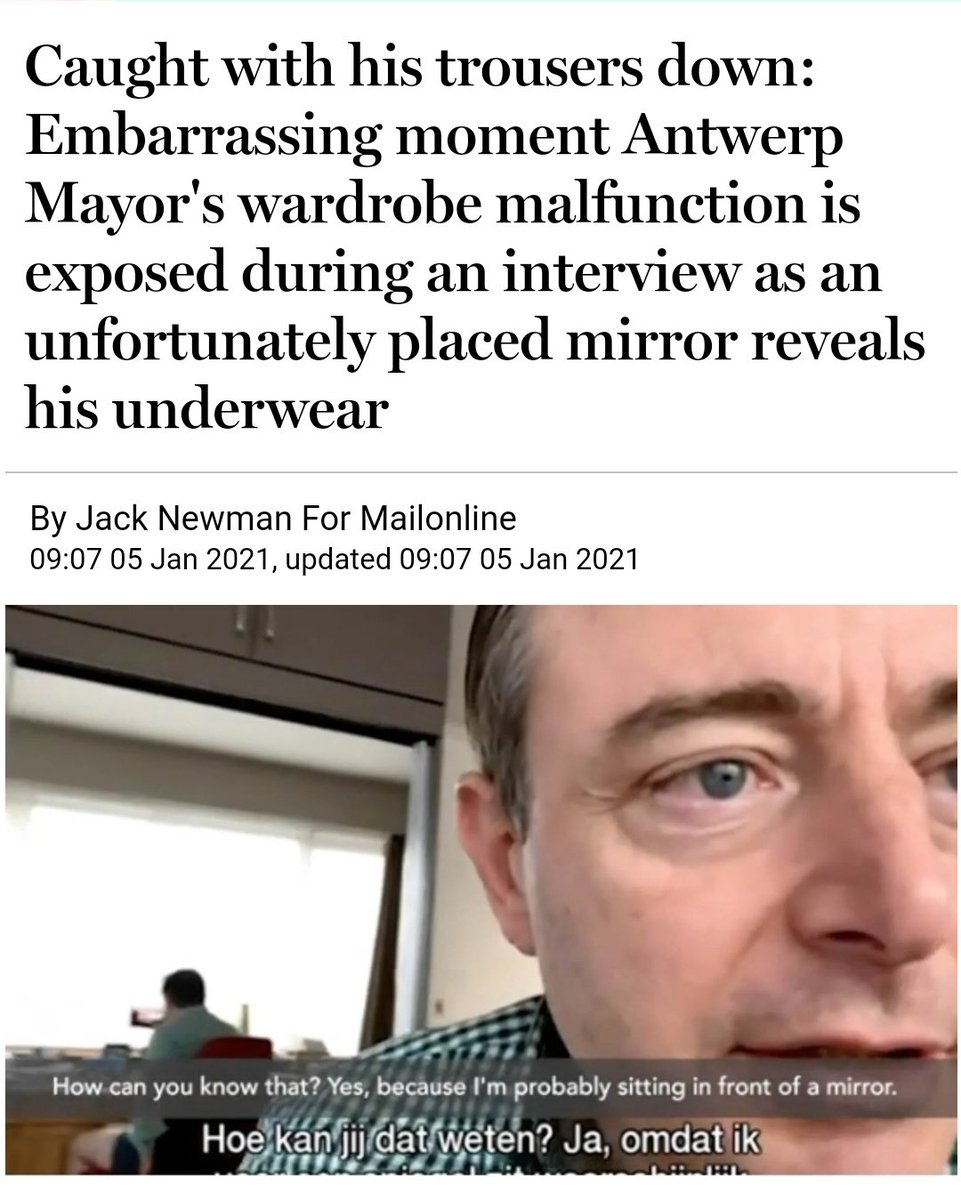

The Mayor of Antwerp suffered an embarrassing wardrobe malfunction after an interviewer noticed he wasn't wearing any pants.

Bart de Wever, the mayor of the second biggest city in Belgium, wore a smart shirt for the radio interview which was broadcast from his own home.

Bart de Wever, the mayor of the second biggest city in Belgium, wore a smart shirt for the radio interview which was broadcast from his own home.

Per this POLITICO story in 2015, Bruno De Wever, Bart’s brother, is a historian who studies the Flemish pro-autonomy movement.

https://www.politico.eu/article/belgium-bart-de-wever-government-flemish-nationalism-n-va-migration-terrorism/

https://www.politico.eu/article/belgium-bart-de-wever-government-flemish-nationalism-n-va-migration-terrorism/

The New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie, N-VA) had emerged as the big winner of Belgium's 7 June 2009 regional elections.

Bart de Wever was able to transform the ashes of the People's Union (Volksunie, VU) into a big Flemish regionalist party, said Regis Dantoy, https://www.france24.com/en/20100615-profile-bart-de-wever-architect-flemish-nationalists-revenge-belgium

Bart de Wever was born into politics in 1970 in Mortsel, a city near Antwerp.

His father, a sympathizer of the far-right Flemish National Union, registered him with the Volksunie (People’s Union) party as soon as he was born.

His father, a sympathizer of the far-right Flemish National Union, registered him with the Volksunie (People’s Union) party as soon as he was born.

He considered a career as a historian while studying at the Catholic University of Louvain, but his family roots in politics would soon pull him back.

Between 1991 and 1992, De Wever was editor-in-chief of a publication featuring ideas influenced by Catholic traditionalism.

Between 1991 and 1992, De Wever was editor-in-chief of a publication featuring ideas influenced by Catholic traditionalism.

De Wever is seen as both a smart tactician and a charismatic personality.

He once staged attention-grabbing stunts like driving a truck filled with fake money in order to denounce the “scandalous” transfer of money from Flanders to Wallonia.

He once staged attention-grabbing stunts like driving a truck filled with fake money in order to denounce the “scandalous” transfer of money from Flanders to Wallonia.

Belgium entered the coronavirus crisis amid a domestic political crisis.

Now that Belgium has started the first phase of its exit strategy out of the lockdown, politicians are finding that the old political crisis is more virulent than ever. https://www.politico.eu/article/belgium-coronavirus-the-flemish-independence-nationalist-exit-strategy/

Now that Belgium has started the first phase of its exit strategy out of the lockdown, politicians are finding that the old political crisis is more virulent than ever. https://www.politico.eu/article/belgium-coronavirus-the-flemish-independence-nationalist-exit-strategy/

While the south wanted to follow France’s example and close the schools as soon as possible, Flanders (whose economy is more than twice the size of Wallonia’s) was more reluctant.

When Flemish nationalism emerged, Flanders was still dominated by an agrarian way of life, while Wallonia grew through industrialization.

The Flemish economy now outperforms Wallonia’s following the decline of the Walloon coal and ‘heavy’ industries. https://themythofhomogeneity.org/2020/10/29/the-populism-and-sub-state-nationalism-nexus-in-flanders/

The Flemish economy now outperforms Wallonia’s following the decline of the Walloon coal and ‘heavy’ industries. https://themythofhomogeneity.org/2020/10/29/the-populism-and-sub-state-nationalism-nexus-in-flanders/

In Belgium’s 2019 elections, the Vlaams Belang's (VB, Flemish Interest) proportion of the vote rose more than 8% at the federal level and 12% in Flemish Parliament elections.

The N-VA remains the largest party in Flanders.

The N-VA remains the largest party in Flanders.

Statements from both the N-VA and the VB show how advocating for territorial autonomy can be supported by populist rhetoric.

The VB’s language has been more explicitly populist.

The VB’s language has been more explicitly populist.

Radical right messaging in the 1970s and 1980s did not emerge independently in each European country.

Rather, it diffused transnationally, particularly from France’s Front National. The VB’s founding members had a close relationship with the Front National.

Rather, it diffused transnationally, particularly from France’s Front National. The VB’s founding members had a close relationship with the Front National.

The N- VA has continued to ally itself with sub-state nationalists in Catalonia, showing support during and after the Catalan independence referendum.

“In Belgium the two cultures know very little about each other because they speak different languages. There are singers known in one part, not in the other. Television is different, newspapers, books.” https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/04/arts/04abro.html

A century ago Émile Verhaeren, the Flemish Symbolist poet, who was born in Sint-Amands, near Antwerp, and educated at the University of Leuven, wrote in French.

Now the university has split into two, the one Flemish, the other French and moved to Wallonia.

Now the university has split into two, the one Flemish, the other French and moved to Wallonia.

“Educated Flemish spoke in French. But then the electoral system changed and allowed everyone to vote, and more power went to the non-French-speaking Flemish middle and lower classes.”

“Even today, there is still a feeling among Francophones that French is so important they don’t need to learn Dutch.”

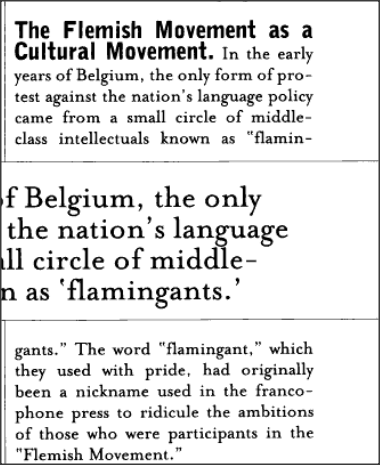

Members of the Flemish movement from a small circle of middle-class intellectuals were once ridiculed as 'flamingants'.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43134211?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3Ad226b71a6a6b226d667caf0e6017af47&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43134211?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3Ad226b71a6a6b226d667caf0e6017af47&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents

In some way, Belgium is a contradiction.

On the one hand, the country has greatly contributed to the political construction of Europe. On the other hand, it remains mired in the ongoing conflict between the two main linguistic groups.

On the one hand, the country has greatly contributed to the political construction of Europe. On the other hand, it remains mired in the ongoing conflict between the two main linguistic groups.

Confronted with the dual movement of supranational integration and subnational regionalism, Belgian political institutions have been profoundly transformed since World War II.

Because of its intricate political and linguistic makeup, Belgium provides researchers interested in inter-group relations and inter-group conflict with a particularly rich field of investigation.

The rise of Walloon nationalism came only after World War II.

Until then, the steel and mining industries of Wallonia had been the engines of Belgium’s prosperity.

Until then, the steel and mining industries of Wallonia had been the engines of Belgium’s prosperity.

With time, more and more powers were transferred from the federal level to the communities and regions.

Currently, French-speaking political parties consider these evolutions sufficient, whereas some Dutch-speaking political parties want more constitutional reforms.

Currently, French-speaking political parties consider these evolutions sufficient, whereas some Dutch-speaking political parties want more constitutional reforms.

Specifically, some Flemish representatives take issue with the fact that Wallonia receives more in terms of public expenditures than it contributes to the state revenues.

The largest political party in both Flanders and Belgium, the Flemish nationalist N-VA, is at the forefront of these requests.

Bart De Wever has come to embody French-speakers’ fears that Belgium would eventually split.

Bart De Wever has come to embody French-speakers’ fears that Belgium would eventually split.

French-speakers usually believe that their ancestors were more often resistance fighters and the Flemish more often collaborators during both wars.

The Flemish usually believe that the repression of collaborators was more severe in Flanders than in Wallonia.

The Flemish usually believe that the repression of collaborators was more severe in Flanders than in Wallonia.

After World War I, German-speaking territories, located to the east of the country, were ceded from Germany to Belgium in compensation for losses and damages caused by the war.

They were regained by Germany during World War II only to be ceded back to Belgium after the war.

They were regained by Germany during World War II only to be ceded back to Belgium after the war.

Because of its small size and limited contribution to institutional reforms, the German-speaking community has usually been neglected in analyses of the Belgian linguistic conflict.

Whereas more than half of the Flemish population has a good to excellent command of French, people having a good to excellent command of Dutch represent only 31 and 16% of the population in Brussels and Wallonia, respectively.

Except for Brussels and the facility municipalities, all Belgian geographical areas are under strictly monolingual regime.

The same can be said about the media system, with each community having its own public broadcaster, while the commercial radio and television stations are also monolingual.

Some of the central traits of the Flemish stereotypes about French-speakers are typically associated with high-status groups.

These traits, commonly found in surveys, are “arrogant”, “contemptuous”, “haughty”, or “feeling superior”.

These traits, commonly found in surveys, are “arrogant”, “contemptuous”, “haughty”, or “feeling superior”.

Individually, none of the previous characteristics is unique to the Belgian conflict.

Canada and Switzerland, for instance, are also hosts to non-violent conflicts between their linguistic communities.

Canada and Switzerland, for instance, are also hosts to non-violent conflicts between their linguistic communities.

The Flemish tend to view the linguistic conflict as more ancient (median year of the onset of the conflict = 1830) than French-speakers (median = 1930), for whom the linguistic issue became a reality only when the Flemish movement radicalized.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter