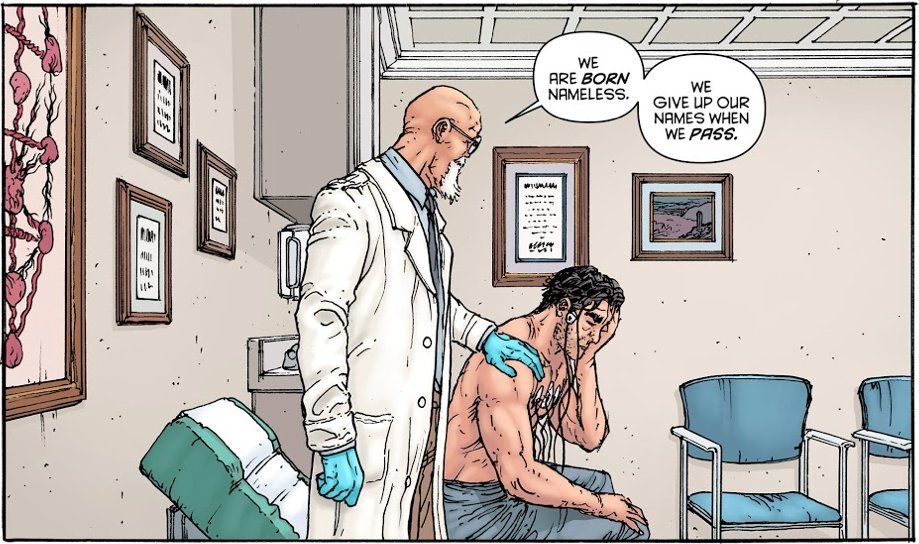

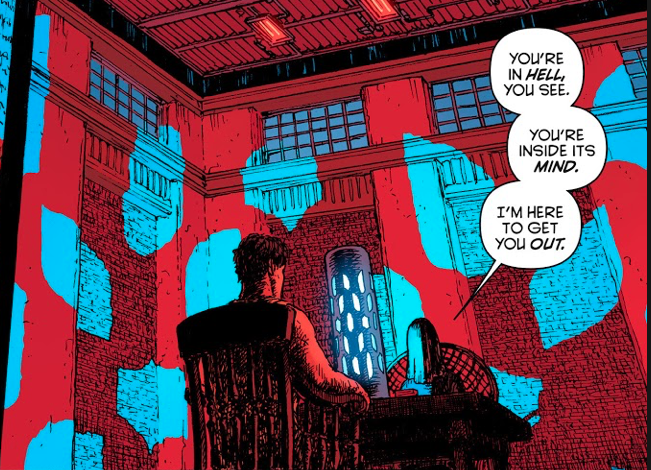

There's an eerie, dreamlike quality to the panel layout in the beginning where the images don't just bleed into one another, but circle back and forth from one wave to another.

Roughly around this time, Grant Morrison's mom died (specifically, shortly before the last round of Batman Inc.). The significance of its invocation here is as important as the invocation of their father's death in All Star Superman.

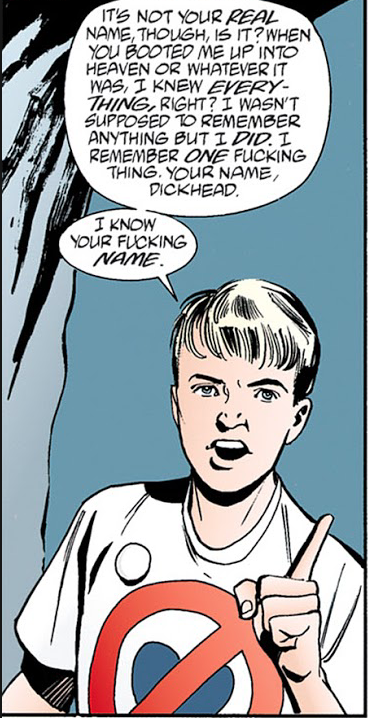

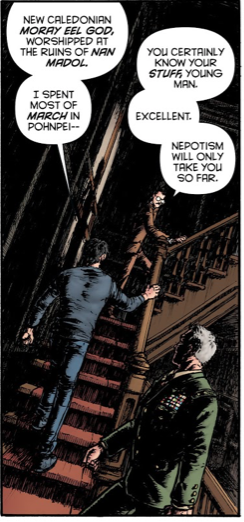

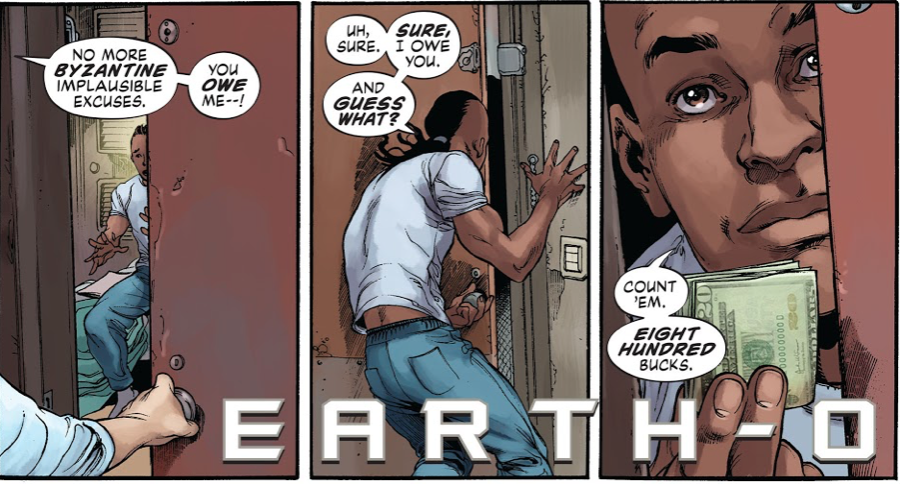

For all that this is a moment of swagger on the part of our nameless protagonist, it is also a moment of foreshadowing. Though he's flipping the script, he nevertheless sticks within the narrative he's trapped in. "It's always too late for the likes of me, hen."

One of the earliest magic tricks a kid will learn is pulling a quarter out from behind an ear. In some regards, this highlights the transactional nature of magic. "There's always a price," as has often been said.

Morrison would make the implications of aspect of magic (and, subsequently, storytelling) in their contemporary Maxi-series, The Multiversity.

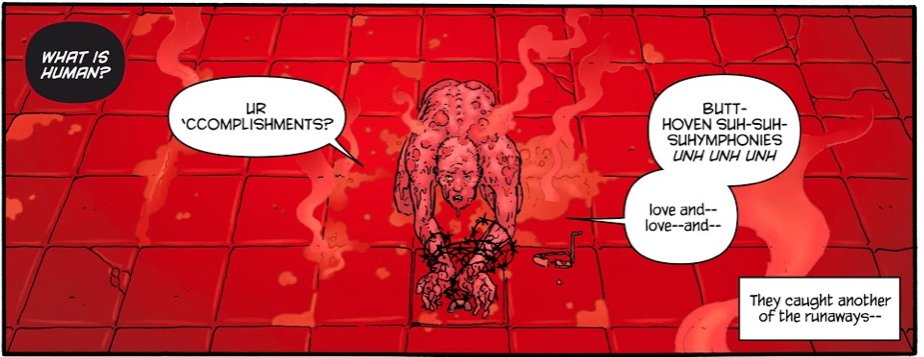

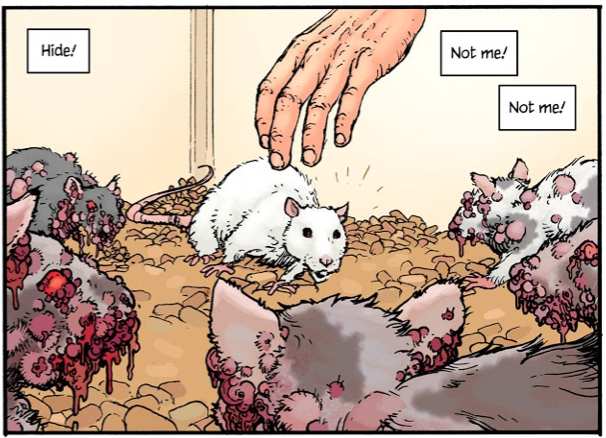

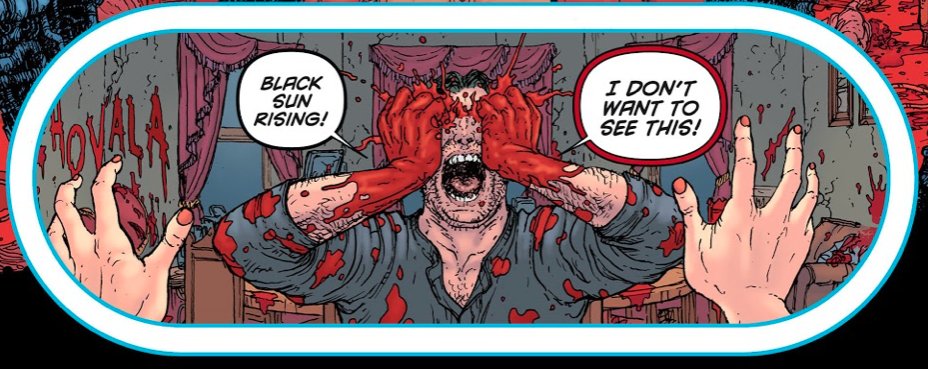

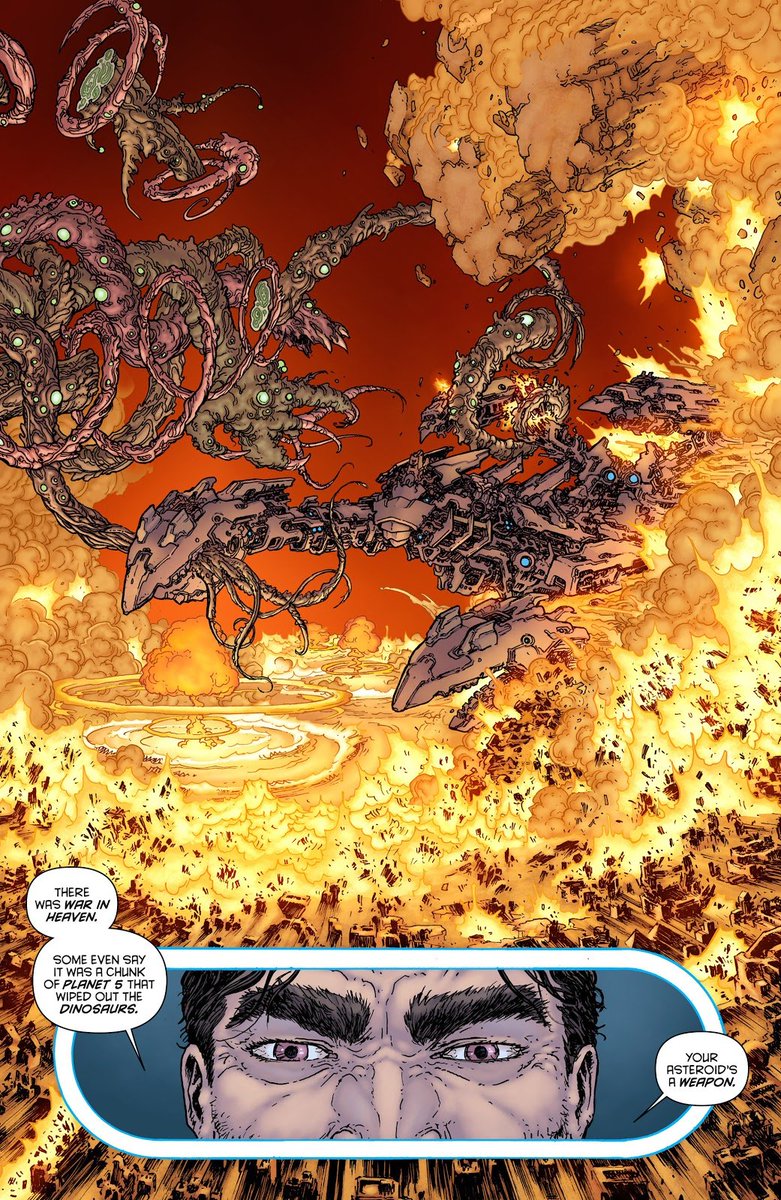

Chris Burnham is an extremely terrifying artist, capable of showing the right amount of detail to make the horror of the scene effective.

There are many silent invocations of Alan Moore throughout Nameless, one notable one in the penultimate chapter, but Moore is more of a lurking presence on the side than a punching bag. This isn't about a Northamptonite. This is about a Glaswegian.

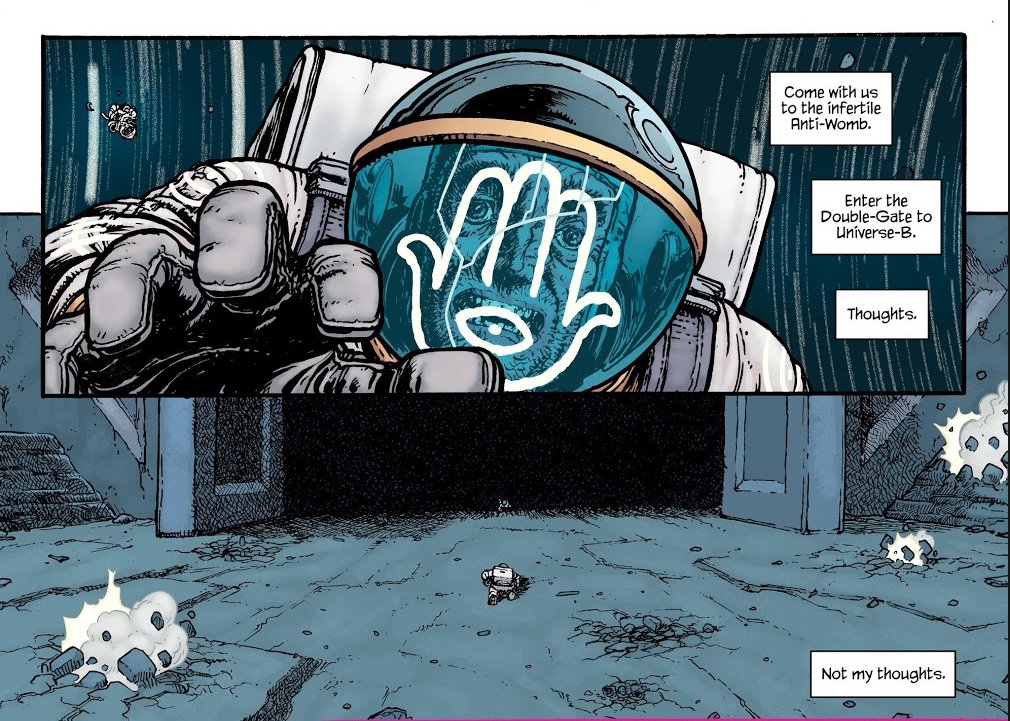

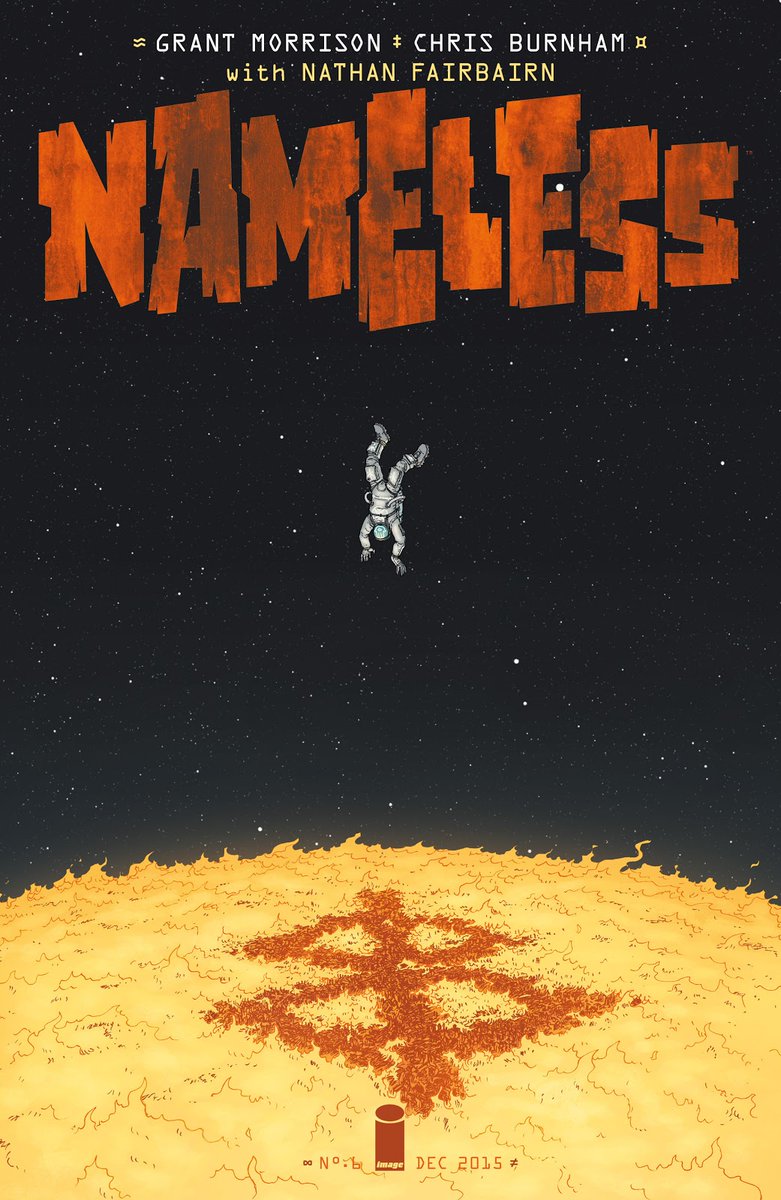

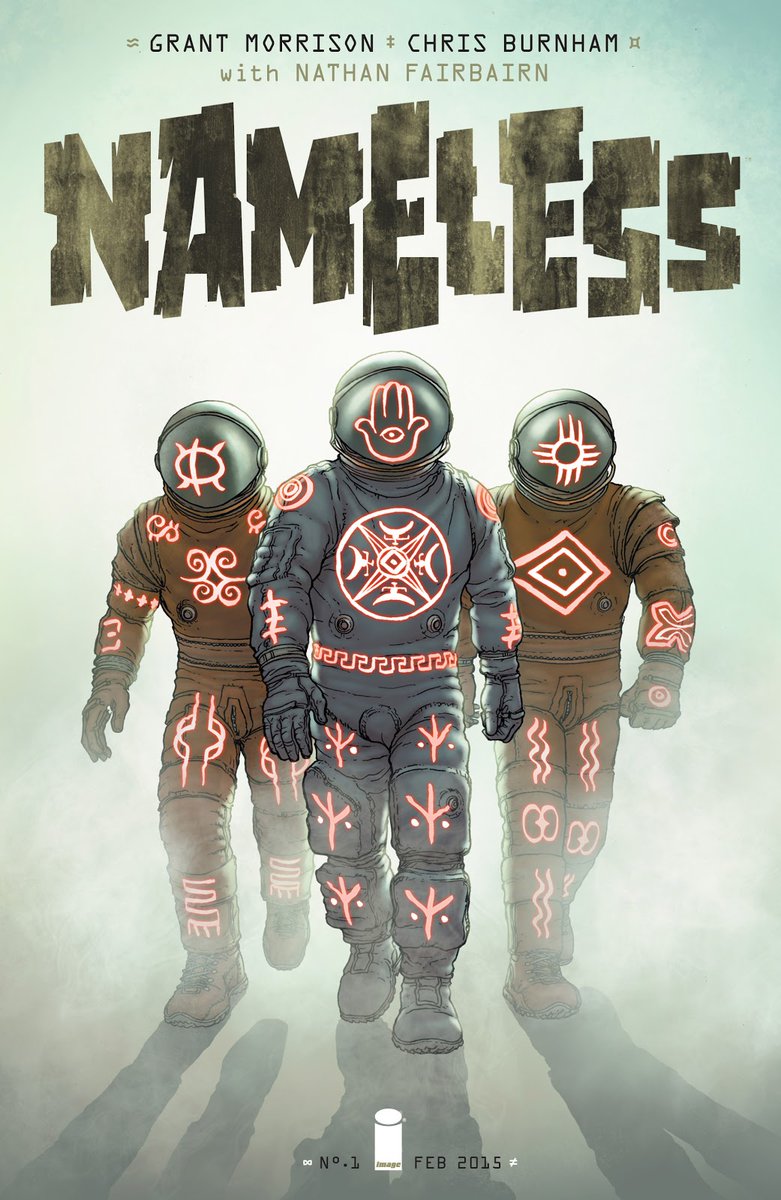

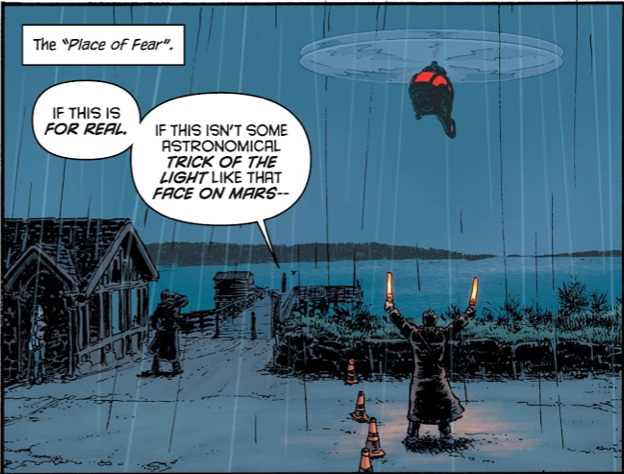

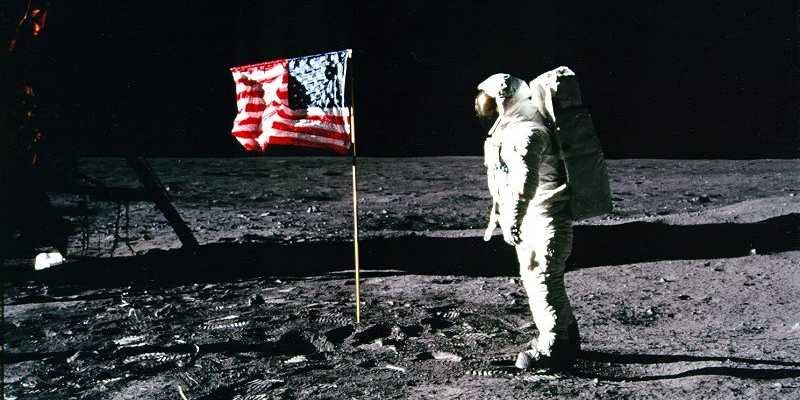

The politics of space based utopianism have always been, to one degree or another, fucked. From the militarism of Star Trek to the implicit implications of space colonies, there has always been a reactionary tinge to living among the stars.

Our conception of space travel has been consumed by a desire to win brownie points against the Russians during the Cold War. Inextricably tied to fascism by our usage of Nazi scientists to get us there.

Space is a beautiful, wonderful place. But our imagining of traveling there has always been in the context of conquering the Dark Side of the Moon like we did Darkest Africa.

Something Nameless hammers in over and over again is how much of an asshole our hero is. Every little detail from how people react to him to how he thinks of them highlights the smug, self satisfied asshole who thinks he's so much better than everyone else.

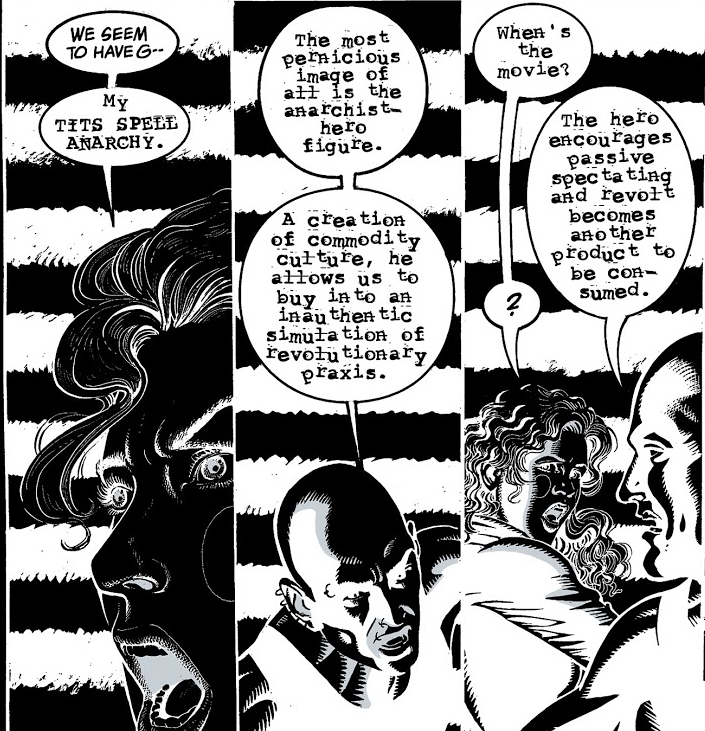

It's often missed on the comic book and sci-fi crowd because we've spent decades being told how great such assholes are. Be they Tony Stark, Spider Jerusalem, or (to use a modern example) Rick Sanchez.

But, as Nameless goes on, we see the full futility and pointless cruelty at the heart of such men. How they ruin the lives of people they claim to care about, toxics themselves from living their best life, and ultimately make the world a worse place to live in.

Within the work of Morrison, the subject of war is the most horrifying thing ever. Often expressed via the idea of the bomb (note the mushroom clouds), War is something good can never win within Morrison's viewpoint.

Be it the War in Heaven between the New Gods of Apokolips and New Genesis, Society of Superheroes' multiversial war, or the climactic arc of their Batman, War always ends badly for the goodies.

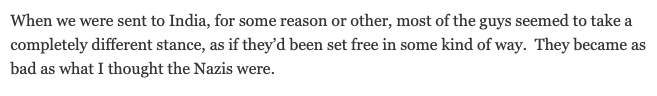

The goodies can win the post war, certainly. But never the war. Because war, ultimately, is pure evil. This Morrison learned from their father, who served in the second World War to fight Nazis, only to discover that he was to be sent to India.

To his horror, Walter Morrison learned that the soldiers were actually expected to treat the Indians as if they're not people. Being a person of moral character, Walter did his best to stop the worst impulses. He would be locked up for this.

It is this horror that Morrison feared and imparted unto his son via the iconography of the Bomb. For what is the Bomb if not the idea of imperialism hammered into being?

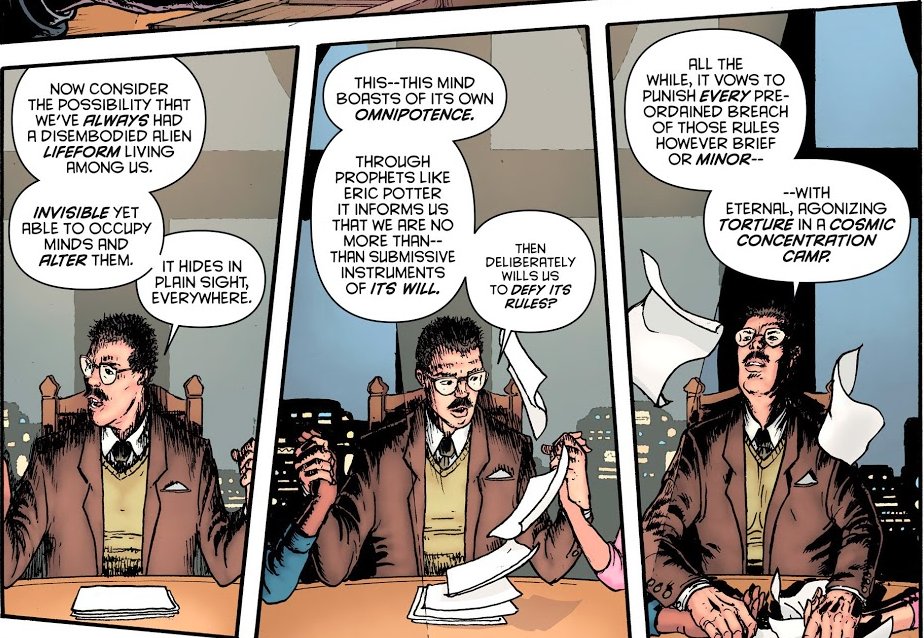

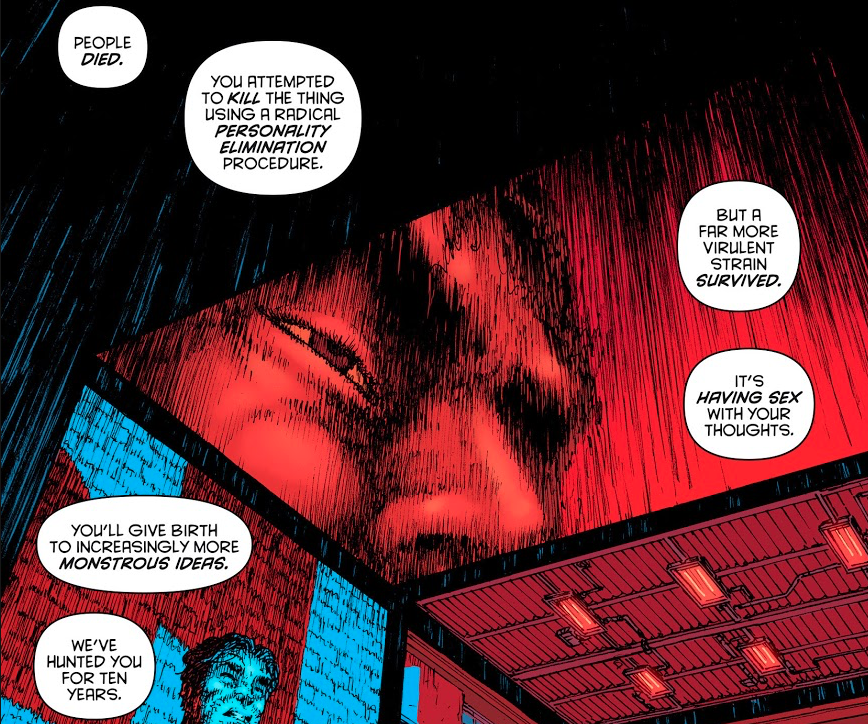

During this phase of their career, which I've lovingly called the "Grant Morrison is Garbage and Here's Why" trilogy, Morrison has had an interest in what happens when you're infected with Bad ideas, be they Evil Aliens from Planet 5, Ultra Comics, or the Krampus.

The horror of having ideas in your head has long been within Morrison's playbook. Be it The Braille Encyclopedia, The Filth, or Doom Patrol. But it's with this phase that they've turned their gaze more closer to their own work. The rotten implications of their own line of thought

The Filth is the obvious precursor to this, being an explicit inversion of The Invisibles, and where a lot of the seeds of Nameless come from. (From "And the earth rushes up to meet him" by Kelly Kanayama)

Arthurian lore is a major influence on Morrison's bibliography. Be it JLA's Superheroes of the Round Table or Shining Knight's queer remix of the story of Tristain. But those stories were tales of monstrous implications.

The Golden Age of England hid visions of rape, cruelty, and imperialism. Stories of the divine right of Kings to do as they wilt.

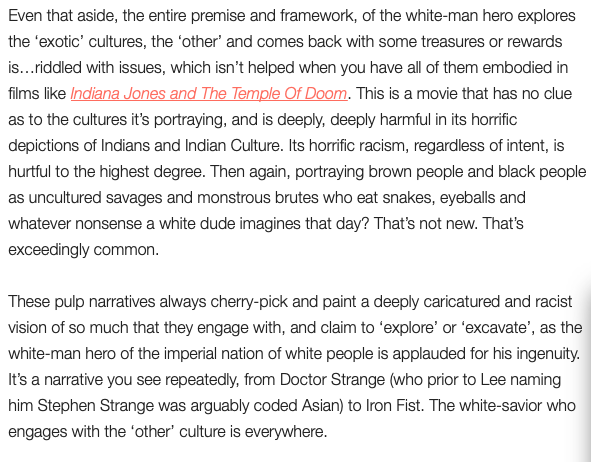

An interesting bit of trivia about Nameless is that it started out as a spec script for an Indiana Jones movie. As @riteshwriter has noted in his article exploring Matt Fraction's American Fiction trilogy, the Indiana Jones films are hella fucked.

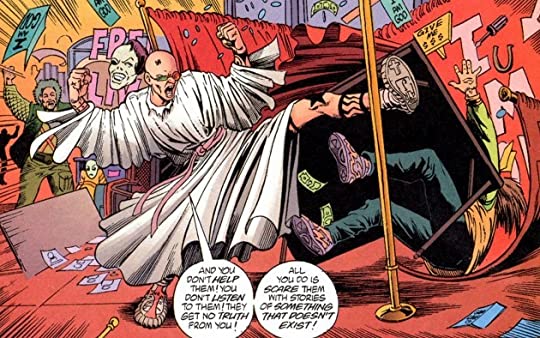

Notably, of The Multiversity's look at the various failings of the Superhero genre, the one it has the most contempt for (after the Nazi one, of course) is the one that focuses on the Pulps.

Not merely content with showing how this line of fiction could fail, Morrison shows how toxic this strain of fiction is, actively highlighting the ways it breaks the superhero while implicitly highlighting some of the racial implications. (Note Doc Fate's costume.)

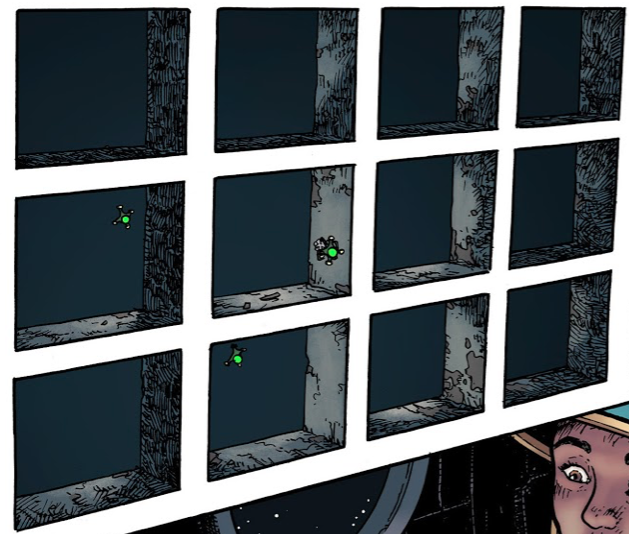

I'd like to take a moment here to say Chris Burnham is a fucking amazing artist. Just the detail on these grates, the way it turns into a grid and what that means in the comic book medium, just everything about this is amazing.

And then there's this glorious page that demonstrates how darkness actually works. Not merely a pitch blackness, but rather a hazy vision of what's right in front of you. You can almost see it, but eventually, something obfuscates the way.

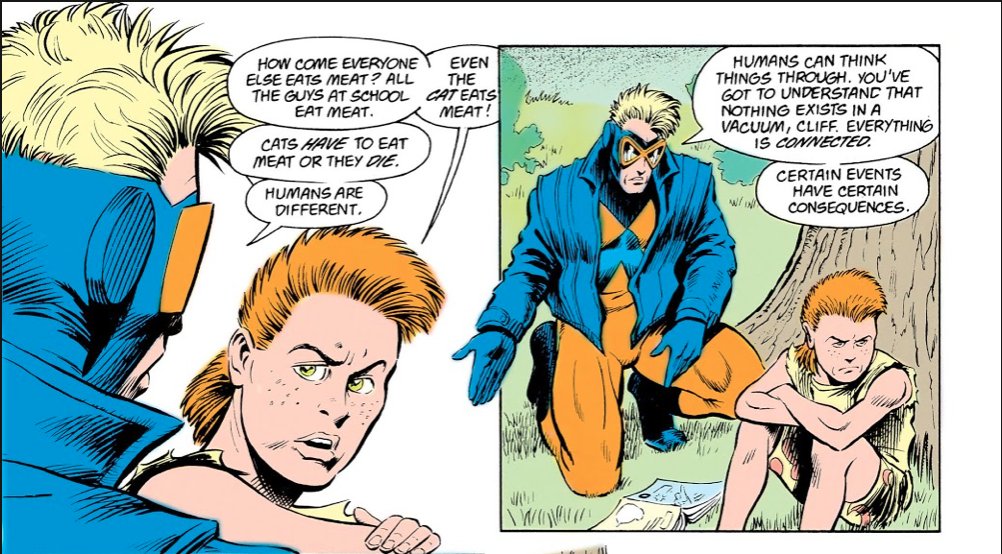

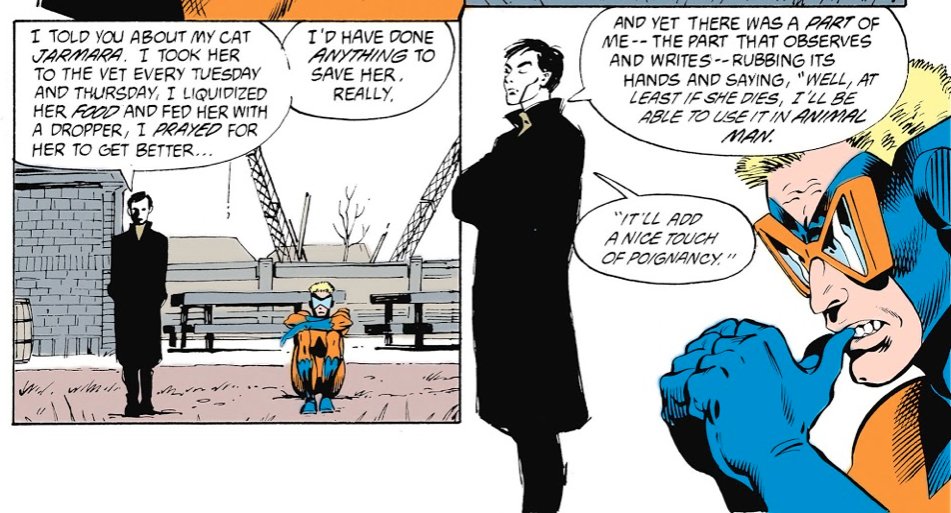

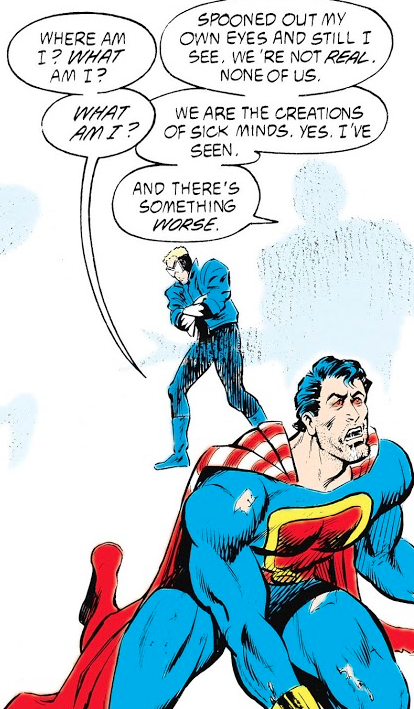

Morrison's first big American Comic was, in part, about the horror of being a comic book character. Of being at the whims of a jobbing writer who is dealing with the death of their cat and a world crueler than they'd like it to be.

One notable sequence involves a character being pulled out of the comic and forced to witness the void beyond the page. Morrison would deal with these implications for a large part of their career, albeit not as explicitly as here.

The horror of Nameless is a similar horror. The difference is that where the God of Animal Man can be convinced to make the death of your family be just a dream, the God of Nameless hates you. Dreams are where it exists, where it can touch you and torture you.

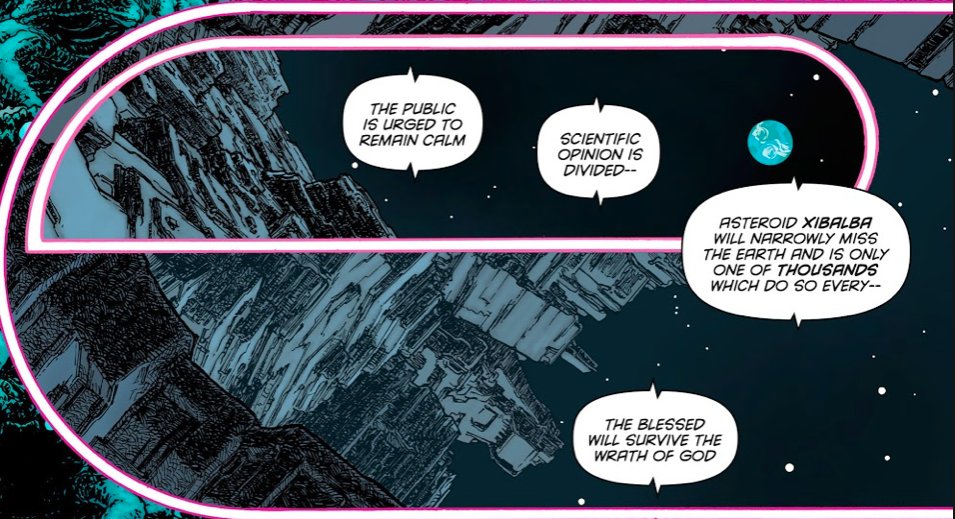

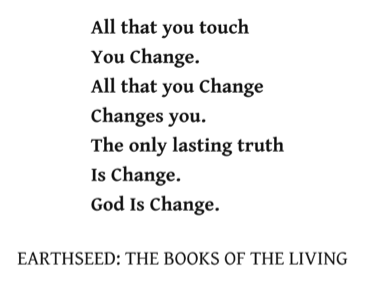

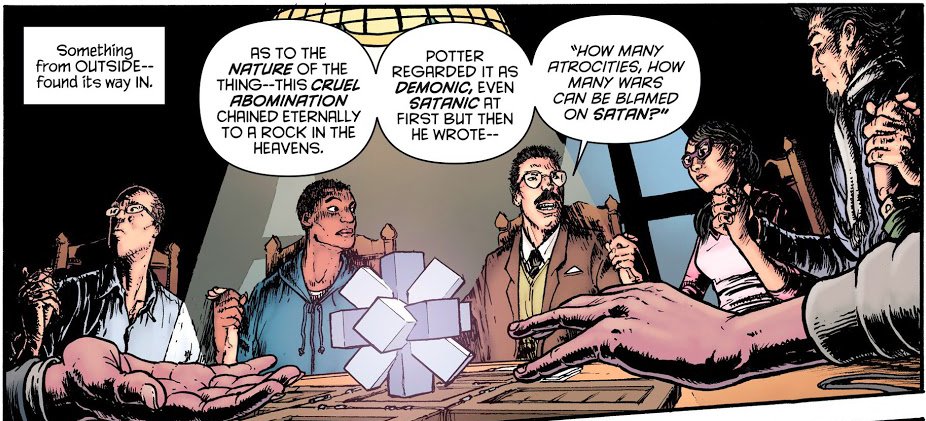

Nameless was inspired by the vision of God as imagined by New Atheists (specifically Hitchens) as written by someone who actually read more religious texts than just the Christian Bible. As such, this small moment of tweaking their nose at religious fundamentalists is notable.

Religion and Morrison is something they haven't written or even talked about that much. It's a largely private aspect of their life, unlike their mystical approach or their superhero fandom.

In the back matter for Nameless' trade, they note that gods, for them, are real as ideas and metaphor, and thus believe in all of them. Though that does not necessitate a worship of all of them, as their choice words for the Norse Pantheon demonstrate.

According to an interview conducted last summer, they were raised Catholic, though that doesn't necessarily mean they still are. Regardless, while interesting, their life is their own business.

In much the same way as Tarantino's The Hateful Eight, Morrison is capable of recognizing nihilistic ideas, but is incapable of expressing them in a way that feels anything but disingenuous for the simple fact that they, in spite of everything, believe in us.

They believe we can be better than we were yesterday. What ultimately keeps the comic from being more than self critique is the inability to fully engage with the ideas (see also the ties between tech billionaires and the divine right of kings).

That being said, this moment of defining humanities accomplishments by the need for suffering (Beethoven was blind) is a truly astonishing moment.

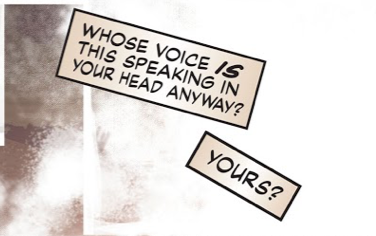

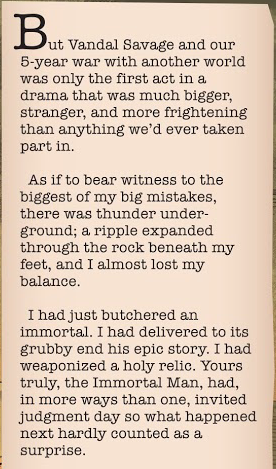

On a first read, this feels like a moment of swagger. That the hero will be able to outwit the evil gods with their name. (Morrison had done this before in The Invisibles.) But, upon closer examination, we should note the fear of who's thinking these words we are reading.

Already, we have had alien thoughts infect our hero's mind, thoughts that look like ones he thought up. The inception of these thoughts, as with the ones in the initial panel, comes from the evil gods.

As befitting of Morrison, the apocalypse we are witnessing is metaphorized through the lens of the scientific cruelty against animals. Lab rats being tested on to find the cure to a disease. Of an uncaring god who does what they want to lesser species because they can.

For triggering reasons, I'm only showing a portion of the panel. In their time writing comics, Morrison has frequently returned to the image of the apocalypse.

Be it Rock of Ages or The Mystery Play, the end of everything as we know has been on the forefront of Morrison's mind for some time. Of course, the roots of Apocalypse fiction lie in political texts.

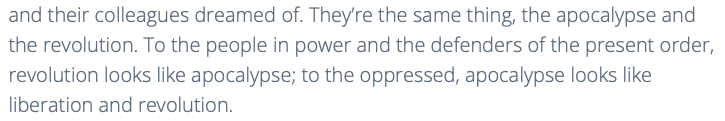

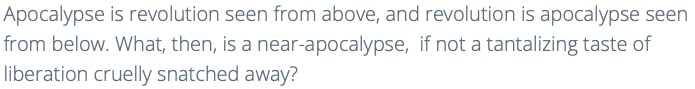

The Book of Revelation, for example, describes the fall of an empire very similar to the one oppressing the Jews at the time of its writing. As Jen Blue notes,

Morrison is aware of this and has come under flack for some of the centrist implications they sometimes fail to acknowledge. Mainly, their terror at the prospect of the revolutionary side of the apocalypse.

In the television series Brave New World, the final episode (written by Morrison) depicts a systemic collapse where the workers systematically murder everyone with a higher rank than them. While not presented as a bad thing, there is a horror to witnessing people die horribly.

There will never be a revolution without a degree of horror. Massive changes are quite terrifying. It's why the Tarot Card that represents change is Death.

Not that all apocalypses are good in Blue's eyes (she is well aware of the evils of a fascist revolution), but that any change from the way things are is bad in the eyes of the superheroes, who fight for the Near Apocalypse more than the Apocalypse.

Prior to Morrison, the big Apocalypse story in Superhero comics was Crisis on Infinite Earths (which Animal Man reacted towards), wherein Worlds Live, Worlds Die, and Nothing Was Ever the Same Again. Except, the ultimate outcome of that apocalypse was John Byrne got Superman.

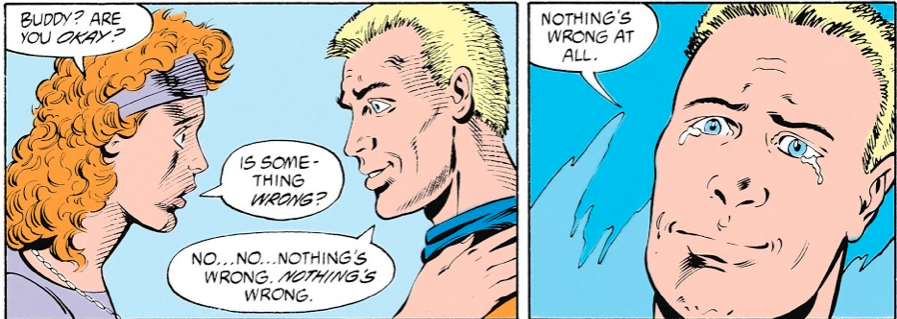

Morrison, for their part, frames the apocalypse as an inherently changing moment. You can't go back to the way things were because you yourself have changed. Buddy may have his family back, but there are tears in his eyes when he sees them alive again.

Batman can beat Leviathan, but his son is still dead. Darkseid and Mandarkk can be defeated, but the world is changed forever.

The failure of revolutions, then, lies in what's done next. Are we going to go back to the way things are (as many a writer following up Morrison has done) or are we going to do something new?

The revolution, the apocalypse, the post-war, all these things can be good or bad, it's just in how we shape it.

A tempting thread throughout comics criticism is the attempt to argue that Scott Snyder is a blockbuster version of Grant Morrison, remixing ideas to make them more palatable to an average audience.

It's surprising, then, that the Dark Multiverse stuff they've done in Dark Nights: Metal wasn't that great given Snyder is better at nihilism than Morrison.

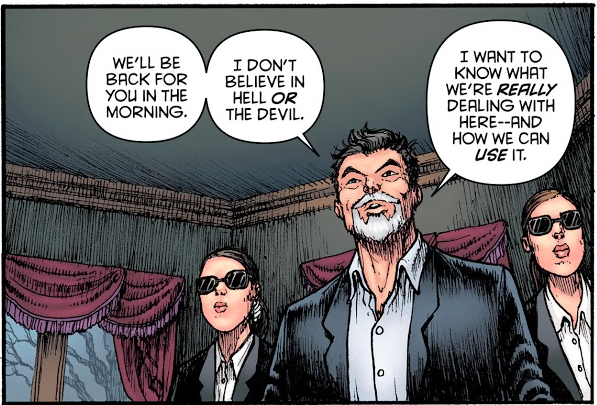

"The apocalypse is caused by a billionaire who wants to know how he can use evil aliens to his own advantage for personal and financial gain" highlights the degree to which Morrison understands the nature of capitalism.

I remind you that Chris Burnham is a fucking amazing artist. Just look at the flatness of the aliens and their technology. Lest I not nod Nathan Fairbairn for his colors. The pink is especially delightful.

Tellingly, they tie the Devil in with god. If, as they note, gods are ideas made manifest, what is the devil if not a bad idea made manifest? All our cruelty, all our hatred, all our jealousy. The Devil is the name we give to the things we hate.

As has been noted a lot lately, Morrison is a critic. In contrast to Moore's historical approach to fiction, Morrison approaches things from a critical lens. There's certainly an anxiety within this lens: "how do I know if I've gone too far in my critique?"

But it's nevertheless there. And it can't be unseen. To attempt to do so, as Nameless notes, is to let yourself open to bad ideas. Reactionary beliefs that there was such a thing as a golden age we've walked away from. If it looks sweet, it is. Don't question what you're seeing.

Morrison's self critique, then, lies in what they see within themselves. Nameless, then, is what happens should they attempt to deny the analysis they are making. To unsee and unthinkable the ideas they have understood. What will happen if they don't move on.

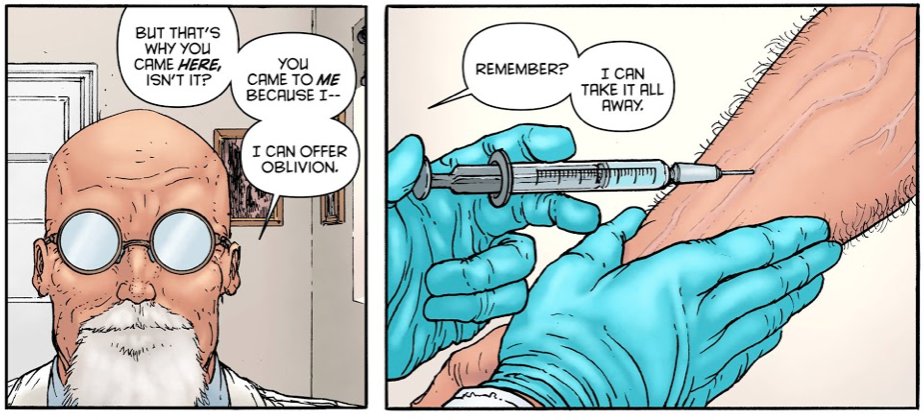

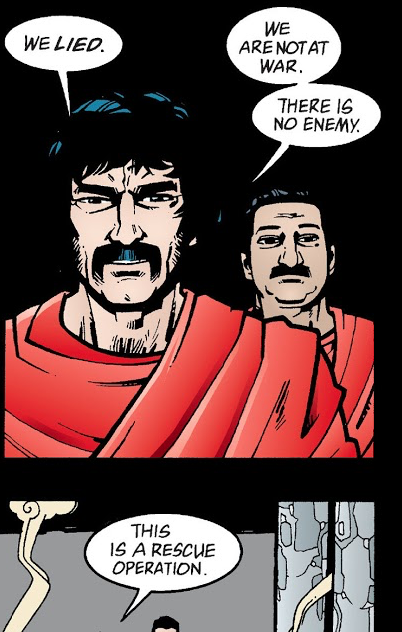

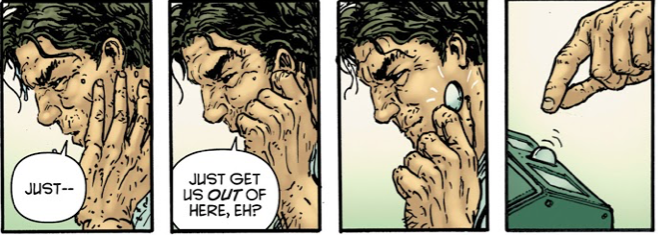

The subject of suicide occurs again and again within Morrison's work. Crazy Jane on the Bridge, Superman after he killed his wife, Regan on the rooftop. Perhaps most interesting about Nameless' usage of suicide is that it frames itself as a rescue mission.

In another inversion of The Invisibles, Morrison framed that story in terms of a rescue operation. Something to save everyone from the worst implications of the apocalypse so we could all, enemy and foe alike, live in a better world.

Nameless, however, rejects this notion. Men like our hero have hurt too many, are too toxic to go on. The rock and roll superhero wizard does more harm than good. Tony Stark, after all, is a billionaire, playboy philanthropist weapons maker we declared the paragon of superheroes.

The consequence of the Heroic Bastard Archetype is often felt upon the women they hurt. An arc of Transmetropolitan featured a former assistant of Spider's who was raped so Spider could get a story. He didn't even remember her.

Here, Morrison forces the Heroic Bastard they once aspired to be to bear witness to their cruelty from the perspective of those he has hurt. And he can't take it. The bastard can't take the suffering of other people.

Around the time Nameless was coming out, there were a number of stories about the implications of killing the moon. Specifically Peter Harnass' Kill the Moon and NK Jemisin's Broken Earth Trilogy.

All three texts highlight the apocalyptic and revolutionary nature of the act of killing the moon. And while Nameless is the weakest of the three texts (Kill the Moon is great, fight me), it nevertheless highlights a revolution.

Morrison explicitly states that the purpose of the story is to rid ourselves of the Bastard Rock and Roll Magician archetype as the toxic waste that it is and all that comes with it. In a comic where violence and griseral horror are shown with abandon, an unseen death is telling.

The Bastard Hero stories would delight in such ultra violence and cruelty. To move forward, we must choose new images.

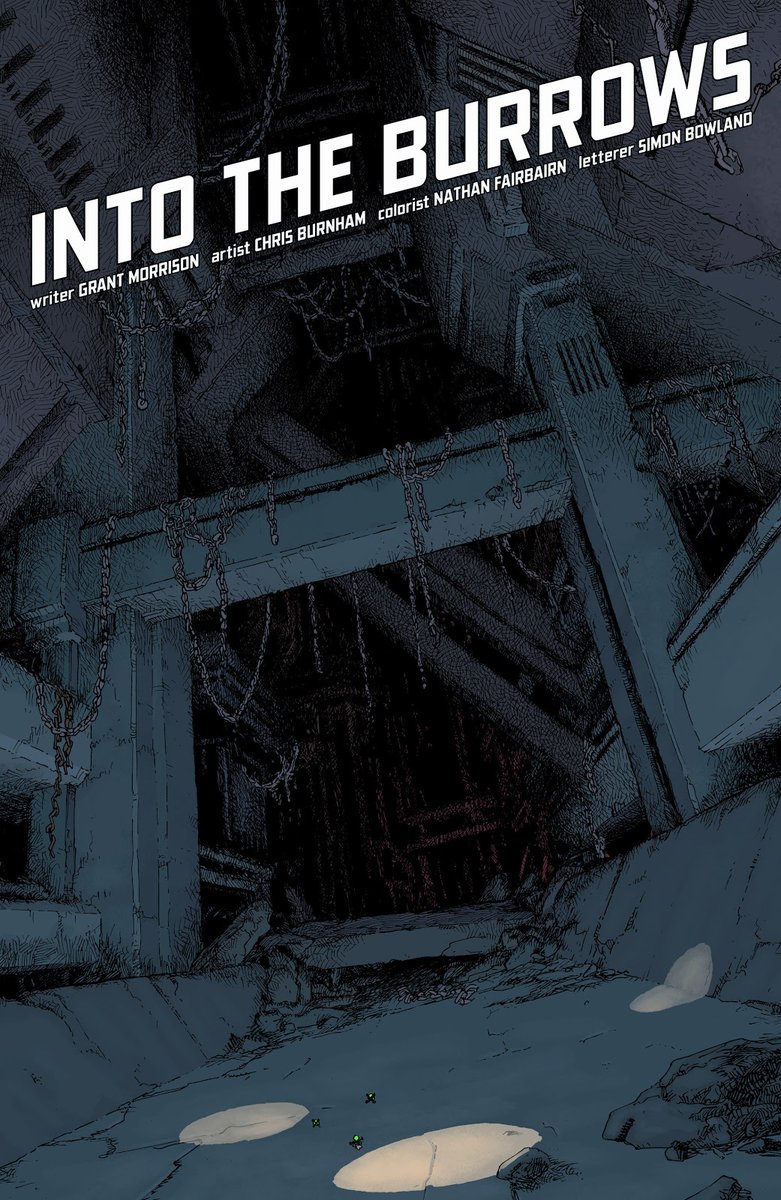

TL;DR? Nameless is great. Probably the weakest of Morrison's self criticism trilogy (it's very much held up more by Burnham's art than Morrison's writing, which still gestures to its thesis more than argues it), but it's a treat to behold nevertheless.

It shows just what was missing from Morrison's decade working just for DC Comics' superhero branch and makes one yearn for a return to spikier material. Hopefully, their work after The Green Lantern and Wonder Woman: Earth One will be better.

Burnham's art, as I've said time and time again, is fantastic, truly capturing the horror of what we are witnessing. Fairbairn remains one of the great colorists of our age. And Simon Bowland's letters demonstrate a clarity of language that keeps us grounded in a strange story.

It's worth a read, even if it doesn't fully get to be as good as it could have been. Though, if you want a nihilistic look at tech billionaires, the end of days, and evil gods, might I tempt you with Neoreaction a Basilisk? https://www.amazon.com/Neoreaction-Basilisk-Essays-Around-Alt-Right-ebook/dp/B0782JDGVQ

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![[Breathes in] AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!!!!!!!!! [Breathes in] AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHHHHHHHHHHH!!!!!!!!!](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Eq0a7BSXcAAfZUV.jpg)