Looking back, I think it is a mistake to say the rationalist community was better at predicting pandemic-related things. Some of them are good predictors in general, including on this issue, but the bigger factor was that the topic was interesting to them. https://twitter.com/kerry62189/status/1344787302762115073

Looking back, I think it is a mistake to say the rationalist community was better at predicting pandemic-related things. Some of them are good predictors in general, including on this issue, but the bigger factor was that the topic was interesting to them. https://twitter.com/kerry62189/status/1344787302762115073

"China hawks" stood out for the same reason--they were interested in the topic. Few other groups were seriously trying to understand the issue. They were either focused on their own lives or distracted by politics. I think most health officials were following instructions.

People who were interested produced more analysis of the situation, and of better quality, so they naturally ended up with better predictions than those who weren't really grappling with it. But I don't think that remained true once everyone was fixated on the situation.

At that point, the quality of predictions evened out more, even though they tended to be wrong in different directions. The people who I think are good predictors on this have not dominated the discussion. But I won't know if they were actually good until this ends.

If they're ultimately validated, their commonalities and relative silence will make for an interesting study. A major commonality is that they have a lot of experience interacting with the public, which I suspect was *way* more valuable than expertise, though many also have that.

I think long-term success in electoral politics is a way better filter for general judgment than we're willing to admit. The broader the voter base, the better. I think most U.S. presidents share a combination of skills that has few parallels.

Related to this, good predictors tend to have moved between several different social classes. This alone will prevent a lot of blind spots. The biggest weakness of intelligence is that myopia can warp it. This is why elite homogeneity/consolidation is such a problem.

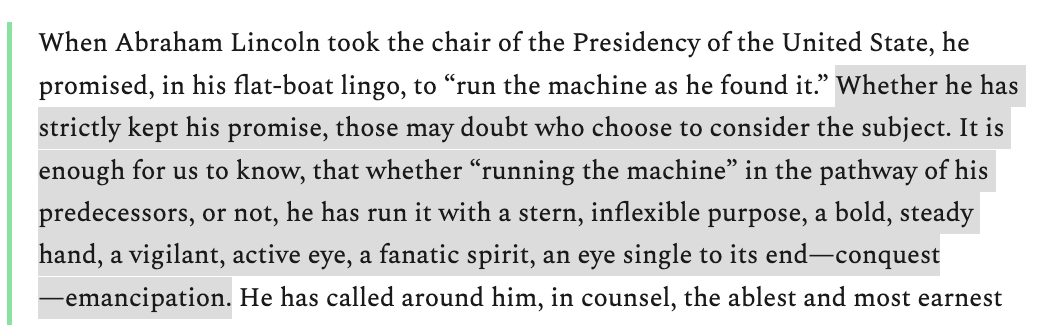

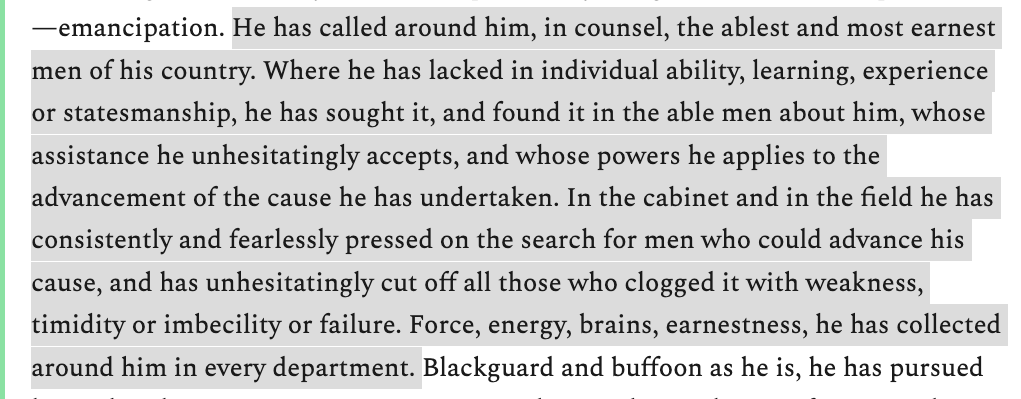

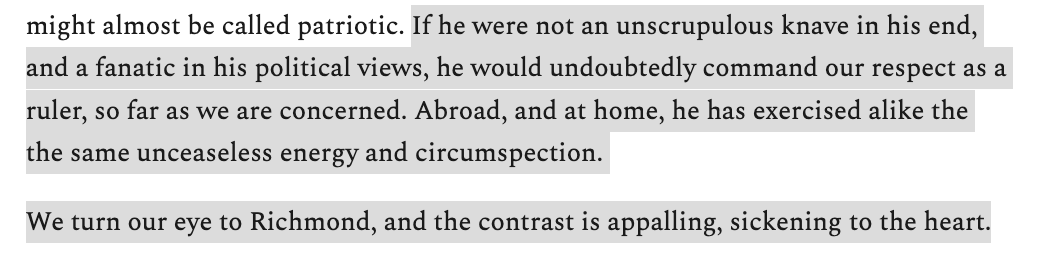

When the Civil War was almost over and the Confederacy was clearly losing, SC's Charleston Mercury, a very pro-secession paper, published an editorial assessing Lincoln's abilities as a leader. It's interesting for a few reasons.

One is the then-common reference to "the machine," which implies a coherent American system, not untethered philosophical ideals. Another is that the Mercury editor believed the war had two goals by 1865: preserving the union *and* emancipation. This was the general view.

And another is the contemporary framing of the "personnel" discussion. "Ablest and most earnest men of his country." There's no reference to any sort of credential, specialty, or "staff," but it can hardly be described as unappreciative of knowledge, ability, and effectiveness.

That is a perfect description of ideal political leadership. Looking at it, it is easy to see what an abdication of responsibility and even basic functionality it is for a politician to say "I'll listen to Science." It's regression, not enlightenment.

Can anyone doubt, after this year, that our standard for leaders should be possessing "force, energy, brains, [and] earnestness"? 2020 has been a lesson in what it looks like when people have brains but not the other three, or, in some cases, force & energy but not the other two.

Also, this was hardly a time when polarization and tribalism ran low, but the editor was not going to make excuses for incompetent leadership just to avoid giving ammo to the other side (and you can bet The Liberator reprinted it and crowed over it).

It's notable how valued presidential "energy" was. I think this is one of the distinguishing traits of presidents--it is an asset in many professions, but I think it is one of the main things voters look for. Devaluing this is one reason the establishment is struggling. /

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter