I've been reading the wonderful book "Cell Biology by the Numbers" ( http://book.bionumbers.org ). Here's a thread of striking things I learned from the book (or related reading)

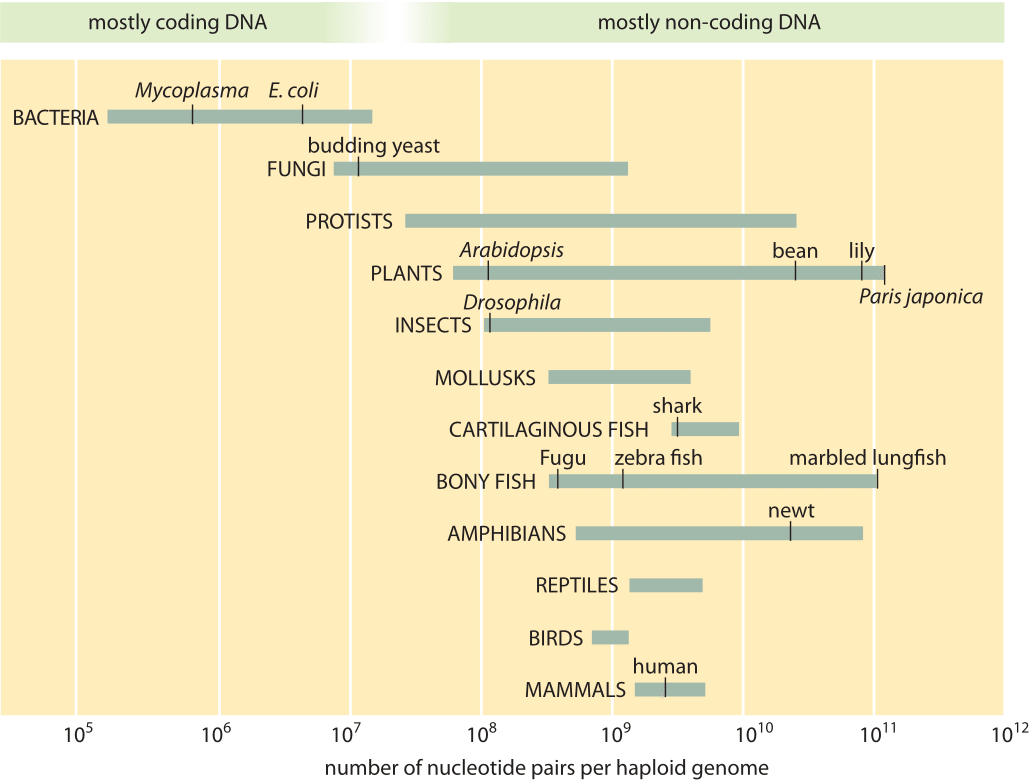

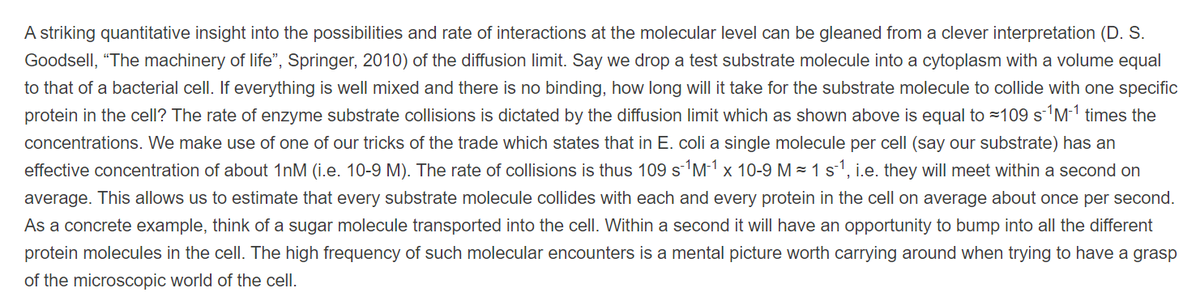

1. In terms of raw genomic information, human beings are

unimpressive. Many plants & amphibians, for instance, have larger genomes. We're not so much the genomic crown of creation as a cul-de-sac of creation.

unimpressive. Many plants & amphibians, for instance, have larger genomes. We're not so much the genomic crown of creation as a cul-de-sac of creation.

I haven't checked, but this graph suggests it may be possible to have a pet snail more genetically complex than you. Or keep (be kept by?) a houseplant that's more genetically complex

2. In fact, the herb Paris japonica has the largest known genome, ~150 billion base pairs, about 50x the human genome. The lungfish has more than 100 billion.

3. What are Paris japonica and the lungfish doing with all that genomic information? No idea! But what a great question!

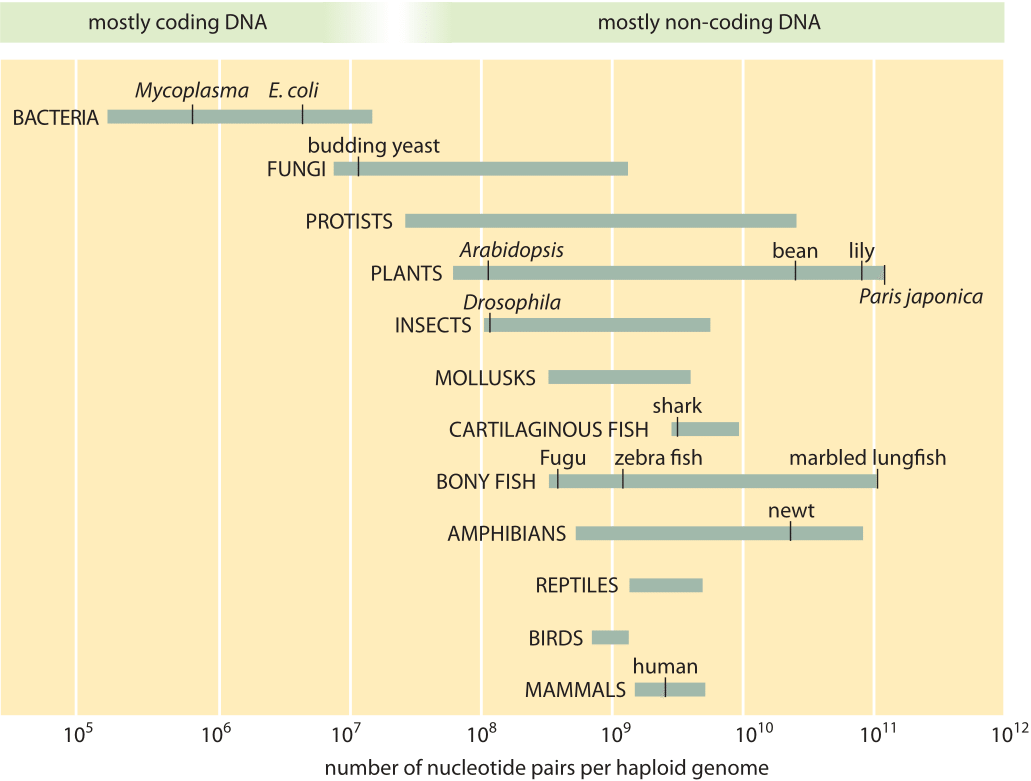

4. With some caveats, a test substrate molecule, "collides with each and every protein in the cell on average about once per second".

Amazingly rapid mixing!

Amazingly rapid mixing!

5. I don't really know what it means for two molecules to collide, or what's required for a reaction to take place (how binary is it? how close do they need to be? does rotation matter etc?) Relatedly: I have no detailed picture of how enzymes speed up reactions, either.

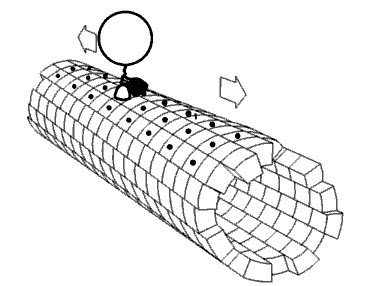

6. A single strand of human DNA would, if stretched out linearly, be about a meter long. It's all bundled up tight inside the nucleus, and a whole lot of fascinating and complex machinery is needed to make use of that rather tight bundle.

7. Related: the volume of a DNA base is ~1 nm cubed, and that of an E. coli is ~1 micron cubed. These numbers are surprisingly useful to know.

(For a physicist, a bit like knowing that visible light has a wavelength roughly 500 nm, that a Hydrogen atom is roughly an angstrom in size, or that light travels one foot per nanosecond. These turn out to be just incredibly useful, over and over.)

8. The smallest virus genome is that of porcine circovirus, which contains 1759 bases, or just over 400 bytes of information(!!).

If you wanted a really viral tweet, you could just put the porcine circovirus genome in your tweet!

If you wanted a really viral tweet, you could just put the porcine circovirus genome in your tweet!

More later, just having some fun.

9. Upon reflection, I don't really know what cells are _for_. (I know, I know, that may be the wrong framing entirely.) Should I think of them as little factories, taking simple inputs (sugars etc) and pumping out complex proteins? Not sure, exactly.

10. If you look naively at a lot of diagrams, it often seems the cell wall is a relatively small part of the cell. In yeast, at least, it makes up 10-25% of the dry mass of the cell(!) I don't know the % of the volume, unfortunately.

11. There's something like 6 orders of magnitude between small-genome life and large-genome life! In terms of linear dimension it's something like the difference between the height of a large ant hill and the height of Mt. Everest.

12. Related: One thing the book does well is just put in-your-face over and over and over the staggering diversity of life. Protons, electrons, and neutrons are nifty things.

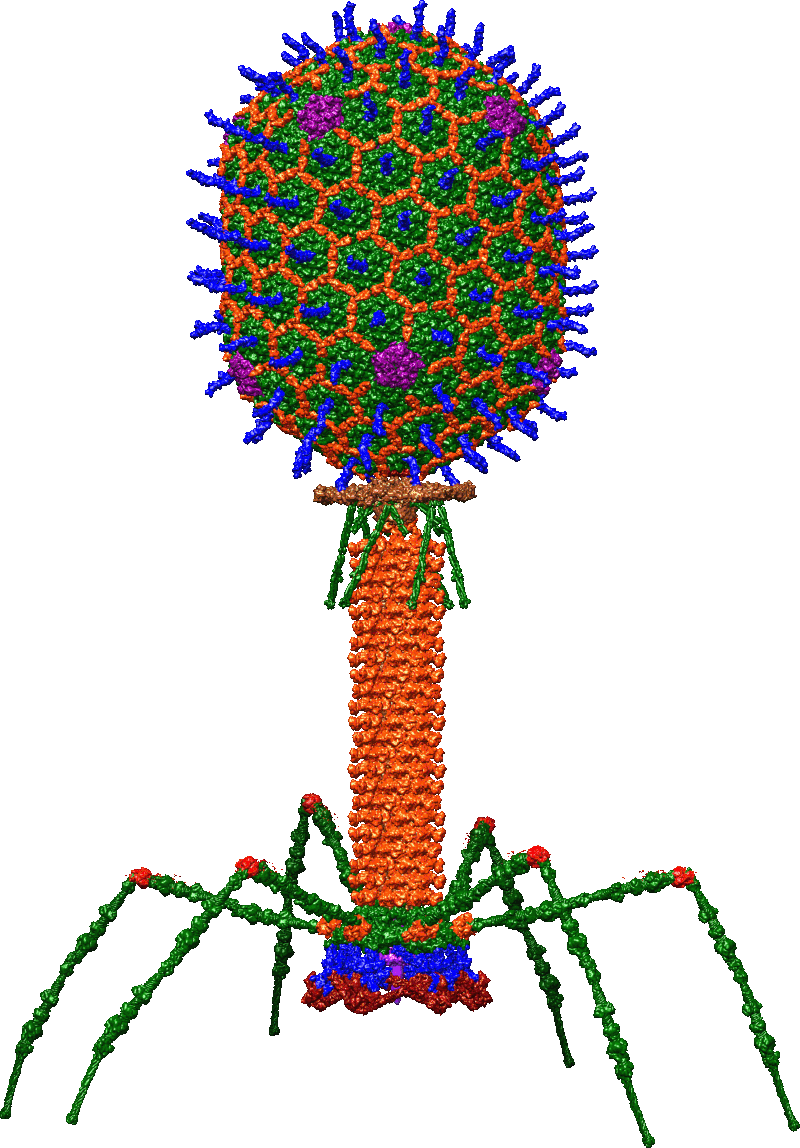

13. Also related: the book rubs in your face the extent to which the biological world is a repository of extraordinary nanomachines which we humans can go discover. It's just this incredible extant resource of ideas and principles and machinery.

And we understand so little about it still. Fun to realize, for instance, that we only pretty recently understood the basic structure of the ribosome - the nanomachine that turns messenger RNA into proteins.

(I know, I know, the broad point here certainly isn't news. Still, the book is fun to read for the onslaught of lovely examples.)

14. Question: Has anyone understood in detail how Coase's "Nature of the Firm" (and the modern followons) relate to multi-cellular life? Lots of very similar problems...

15. Wikipedia's "Molecular Machines" article is as much fun as you should be allowed to have on the Internet: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Molecular_machine

(It's possible I need to get out more. I blame 2020!)

(It's possible I need to get out more. I blame 2020!)

17. @rob_carlson's excellent book "Biology is Technology" has a great discussion of the necessity of predictive quantitative models for design and engineering. Here's an excerpt, which repays thought IMO:

One of the most striking things about "Cell Biology by the Numbers" is that such predictive quantitative models are _lacking_. This isn't a criticism. Rather, it's an opportunity. The book is chock-full of wonderful observations that could, plausibly, help lead to such models.

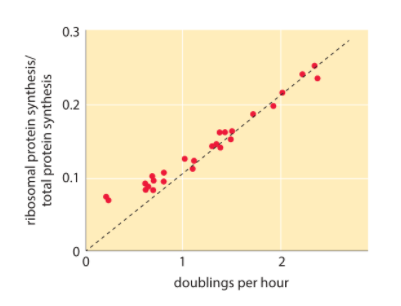

18. A fun set of examples of inchoate models comes from this vignette about the relationship b/w how many ribosomes a bacteria produces, & how often the bacteria reproduces. Very tight relationship! Why, exactly? What else impacts it? Many nascent ideas! http://book.bionumbers.org/how-many-ribosomes-are-in-a-cell/

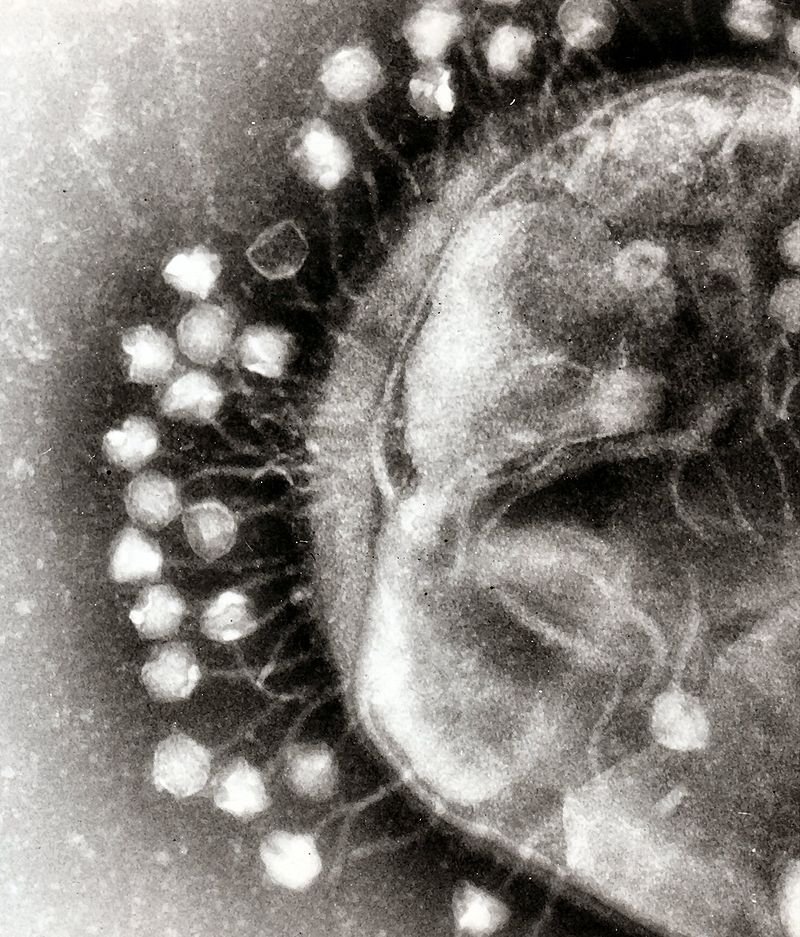

19. Very very roughly, and with much variation, there's about 10,000 ribosomes per femtoliter of cell. The way these numbers are determined are interesting - a trend away from clever weighing techniques, and toward direct microscopy / counting techniques.

20. Roughly, an E. coli is about a femtoliter in size. Common cells are often in the range of femtoliters to picoliters (and may go larger).

A Hewlett-Packard researcher once told me they think about controlling printer fluid with femtoliter precision.

A Hewlett-Packard researcher once told me they think about controlling printer fluid with femtoliter precision.

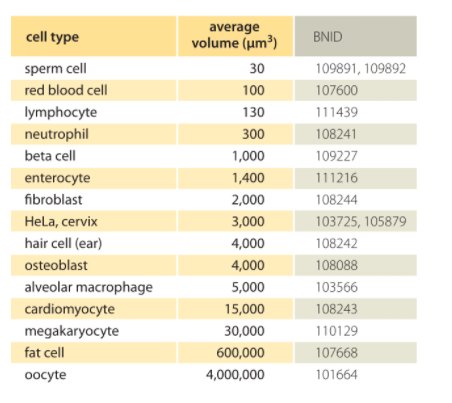

22. Utterly amazing range of variation in sizes of human cells - a factor of more than 100,000!

It's incredible that all these things are called "cells". If I met a person 100,000 times larger than me, I'd think a new category was called for!

It's incredible that all these things are called "cells". If I met a person 100,000 times larger than me, I'd think a new category was called for!

In general, one of the main things I'm getting from the book is that many categories of biological thing have far more variation than I'd previously appreciated.

23. "The fact.. all organisms are built of basic units, namely cells, is one of the great revelations of biology.. [O]ften now taken as a triviality, it is one of the deepest insights in the history of biology...

... & serves as a unifying principle in a field where diversity is the rule rather than the exception."

[Loved this. One of those things so easy to overlook until someone really knowledgeable points it out. And then can keep you thinking for decades.]

[Loved this. One of those things so easy to overlook until someone really knowledgeable points it out. And then can keep you thinking for decades.]

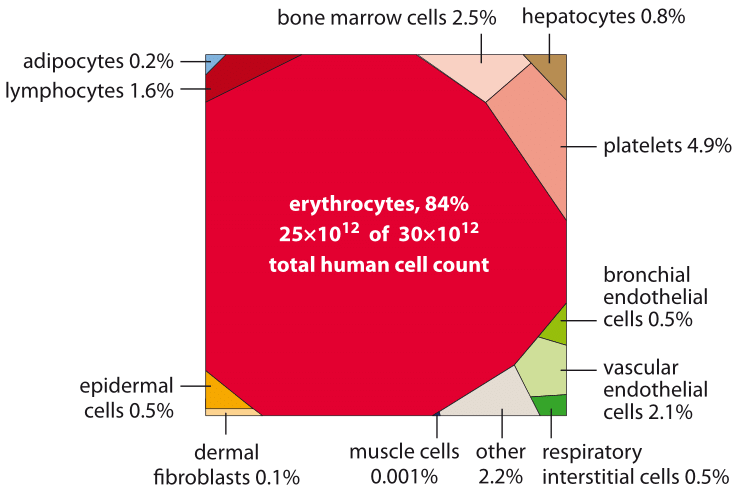

24. Fun to see human cell types broken down by number in the body. We're red blood cells (84%), platelets (4.9%), plus ~11% everything else. Of course, by mass would be a very different story!

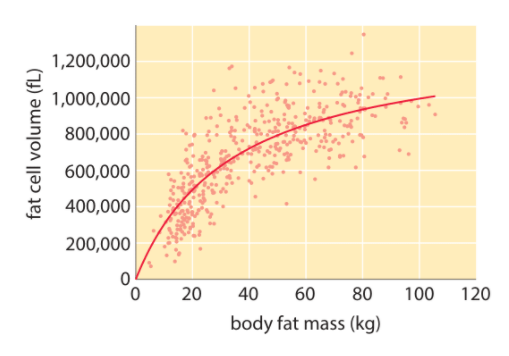

25. Our fat cells get bigger as we do! Isn't that cool? Though the relationship is certainly not linear. Why does the curve have the shape it does?

Also: those are some big cells! A million fL is a cube ~0.1 mm on a side, ought to be quite visible to a human eye.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter