A bit of debate on Irish Twitter today about #Ireland and #Empire, so I wanted to dig into how this worked through the life of one poor Irish emigrant... https://roarmag.org/?p=58657

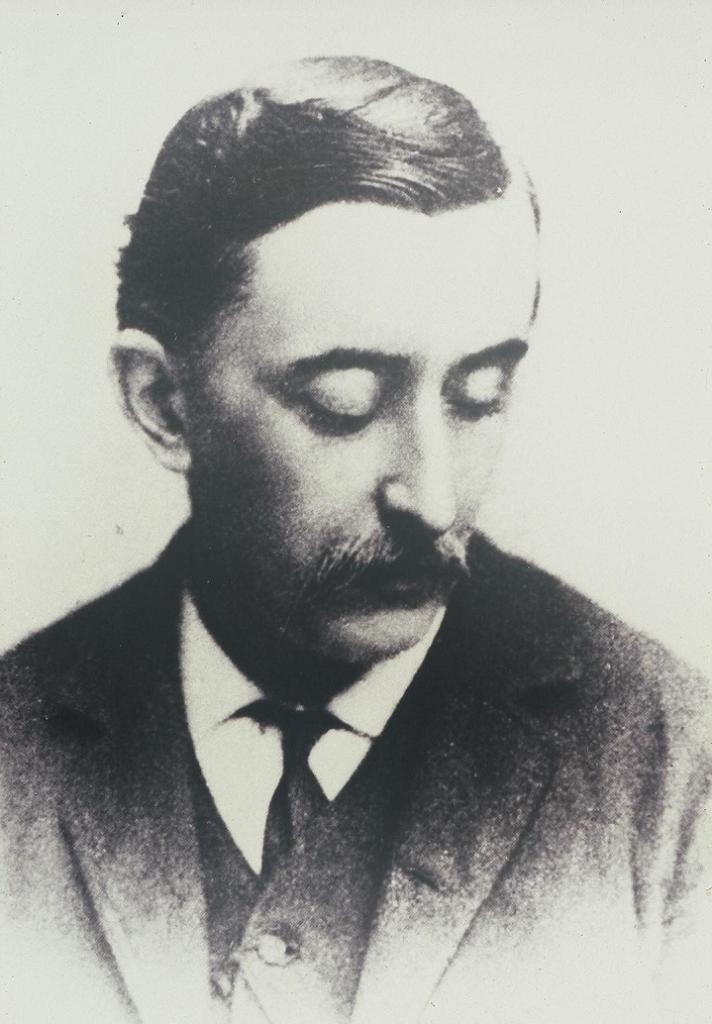

This is Laurence Carroll, born in Booterstown in 1856, emigrating to Liverpool then NY.

A sailor and hobo, radical in the States and then an anti-colonial activist in today's Burma, Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Japan, Thailand, Bangladesh, India....

So far, so simple (ish).

A sailor and hobo, radical in the States and then an anti-colonial activist in today's Burma, Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Japan, Thailand, Bangladesh, India....

So far, so simple (ish).

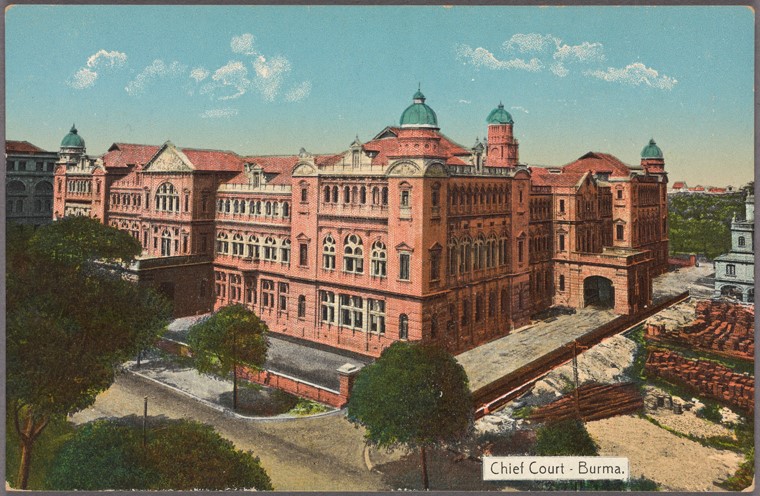

But his 1911 trial for sedition in Rangoon is under the Chief Court Judge, the Hon. Daniel Harold Ryan Twomey, a Catholic from Carrigtwohill, educated by the Jesuits and a senior member of the judiciary ruling colonised Burma.

(And Mary Douglas' grandfather!)

(And Mary Douglas' grandfather!)

He was also targetted by his one-time ally, the equally Catholic (Killarney-born) Edward Alexander Morphy, editor of Singapore's Straits Times.

Irish Catholics were part and parcel of the imperial service class.

Irish Catholics were part and parcel of the imperial service class.

Carroll's sedition trial was perhaps partly provoked by the Irish missionaries of St Patrick's Catholic school and brotherhood in Moulmein, and missionaries in Ceylon where he did a high-profile and controversial speaking tour in 1909.

This was Ireland's "spiritual empire".

This was Ireland's "spiritual empire".

It was a source of pride that if Britain had a physical empire, Ireland had its spiritual empire spreading around the world, bringing the Gospel to the poor benighted heathen (with liberal use of the strap).

But another part of the anxiety that provoked Carroll's trial for sedition was his own Irishness - given how many of the soldiers holding down the "natives" were Irish.

If the Irish stopped being reliable defenders of imperial power, Empire had a problem.

If the Irish stopped being reliable defenders of imperial power, Empire had a problem.

These 3 levels - Catholic Irish in the imperial service class; the Irish "spiritual empire" abroad; and Irish soldiers putting the boot or the bayonet in - were all part and parcel of the colonial enterprise. And they knew it.

There's nothing strange about this – empires usually depend on “divide and conquer”, for the simple reason that they have to pay soldiers from one part of the empire to hold down another part.

It's rarely hard to find people willing to do this.

It's rarely hard to find people willing to do this.

(The imperial ruling class were well aware that the English had started out doing this on behalf of the Roman Empire in Britain...)

A decade earlier the same issue - colonised ppl holding down other colonised ppl - came to the surface when Carroll launched the "shoe controversy" that became a cause célèbre for Burmese anti-colonial activism for the following two decades.

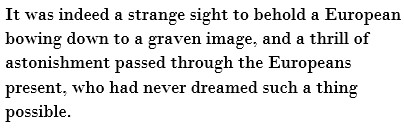

In a dramatic and symbolic moment, he challenged an off-duty policeman wearing shoes (seen as a sign of huge disrespect) on the Shwedagon pagoda in Rangoon at the full moon festival.

"The British had taken Burma from the Burmans and now desired to trample on their religion".

"The British had taken Burma from the Burmans and now desired to trample on their religion".

But the policeman in question … was Indian, happily ruling Burma just like the Irish soldiers.

This willingness to work for empire abroad (even while feeling nationalist locally) was a key part of what made empire possible.

These actions mattered, however we justify them.

This willingness to work for empire abroad (even while feeling nationalist locally) was a key part of what made empire possible.

These actions mattered, however we justify them.

And it's worth saying that people also deserted and became disaffected, at every level.

Terry Fagan collected the story of an Irish deserter who refused to shoot Indians b/c he made the link to poor ppl like himself.

Higher up, Maurice Collis: https://twitter.com/DhammalokaU/status/1332352852031909889

Terry Fagan collected the story of an Irish deserter who refused to shoot Indians b/c he made the link to poor ppl like himself.

Higher up, Maurice Collis: https://twitter.com/DhammalokaU/status/1332352852031909889

So, it's a straightforward fact that Empire depended on Irish, Indian and other soldiers, sailors, missionaries, editors, judges, officers, civil servants and so on helping to do the dirty work.

And sending money back home, retiring to Ireland, etc.

And sending money back home, retiring to Ireland, etc.

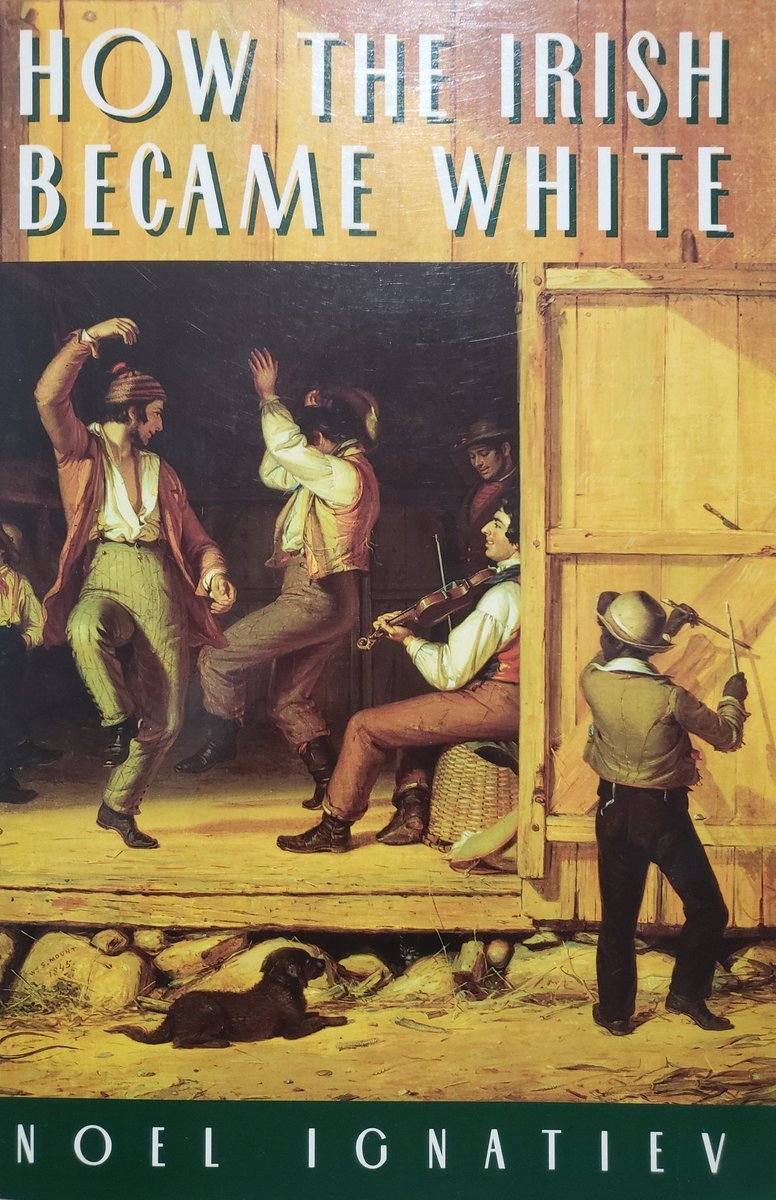

But let's dig a bit more into the choices ppl made. We imagine all the Irish abroad sticking together in tight and often devout communities, reinforcing ethnic solidarity and clawing their way up the pole at the expense of everyone below them.

This helped drive not just Empire in India but "Indian" killing in the States, the formation of Tammany Hall and the murderous US police depts that we've been watching this past year.

But not every poor Irish emigrant played that game (and not everyone who did was poor).

But not every poor Irish emigrant played that game (and not everyone who did was poor).

Let's complicate things further.

Carroll was successful as an anti-colonial activist, and annoyed Irish missionaries, because he had left the fold.

He'd first become an atheist, probably in radical circles in the States like Lafcadio Hearn.

Carroll was successful as an anti-colonial activist, and annoyed Irish missionaries, because he had left the fold.

He'd first become an atheist, probably in radical circles in the States like Lafcadio Hearn.

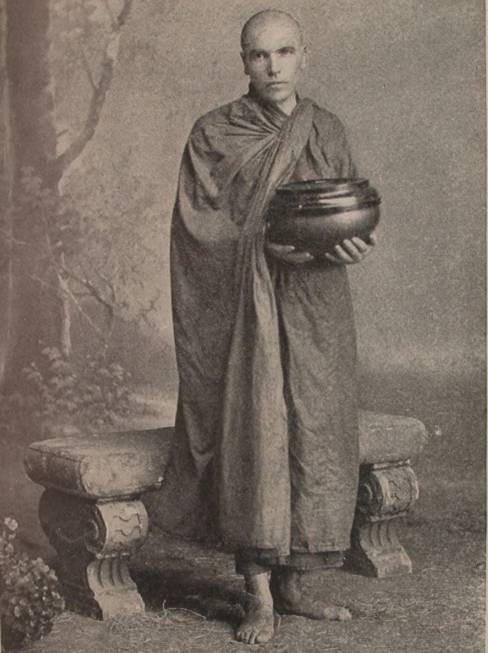

Then he converted to Buddhism and became a monk in Rangoon under the name U Dhammaloka.

Somewhere along the line he stopped being “one of the lads” and defected from the racial privilege that the organised Catholic diaspora sought at others' expense.

Somewhere along the line he stopped being “one of the lads” and defected from the racial privilege that the organised Catholic diaspora sought at others' expense.

He crossed ethnic boundary after ethnic boundary: Irish hobos tried to exclude blacks after the Civil War; he travels through the Montana of the Indian wars; in California Irish labourers tried to exclude the Chinese from the railways and the shipping lines.

Somewhere along this route, Laurence Carroll made the choices that (some) other Irish did not; and these things matter.

He was not alone in this – and these were significant ethical and human choices, with real costs for the people who made them.

He was not alone in this – and these were significant ethical and human choices, with real costs for the people who made them.

Turning Buddhist in Asia was a further step along this road, not just from an Irish Catholic but also from an imperial viewpoint.

In the racial hierarchy of Empire (not identical w the US version) he had "gone native", crossing racial as well as religious boundaries.

In the racial hierarchy of Empire (not identical w the US version) he had "gone native", crossing racial as well as religious boundaries.

After the 1857 Rebellion in particular, racial lines between Europeans and Asians became tighter. There weren't *that* many whites in Asia - but 60% of the world's population.

So a lot of effort went into making Europeans seem special, different from Asians.

So a lot of effort went into making Europeans seem special, different from Asians.

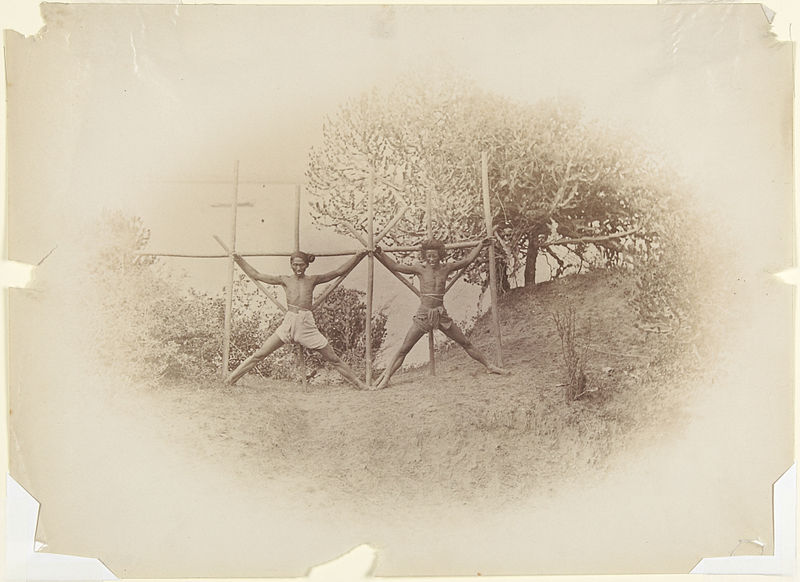

Wearing Asian clothes, fraternising with "natives", doing inappropriate work were all problems. Never mind begging as Buddhist monks do - with bare feet, shaven heads and wearing robes.

Or bowing down to idols.

Or bowing down to idols.

"Poor whites" in Asia tho didn't have quite the same incentives for loyalty to the racial order as in the US (tho most did). If your children weren't born / educated "at home" (in Europe) they slid down the racial hierarchy - never mind if you married a local.

In a country like India up to 50% of the white population were poor. Many were the cast-offs of empire: ex-soldiers and ex-sailors, "beachcombers" doing casual labour, settling down with locals if they could.

They were a source of real anxiety: put into workhouses, deported at times, tracked with mugshots and fingerprints.

They disturbed the racial order and - if e.g. an ex-sailor and ex-docker became a Buddhist monk and anti-colonial agitator - threatened imperial power.

They disturbed the racial order and - if e.g. an ex-sailor and ex-docker became a Buddhist monk and anti-colonial agitator - threatened imperial power.

So there is not just defection from a narrowly-defined Catholic Irish ethnic in-group, but also defection from what Proper Sahibs were supposed to do. Not to mention becoming subordinate to Asian religious hierarchies.

Irish people abroad made real choices, even in 1900.

Irish people abroad made real choices, even in 1900.

And what we see of Dhammaloka's sedition trial is the wider "plebeian cosmopolitanism" of Asian port cities before the rise of ethnically-defined (and often religiously-supremacist) nation states.

This history parallels the Irish in many ways.

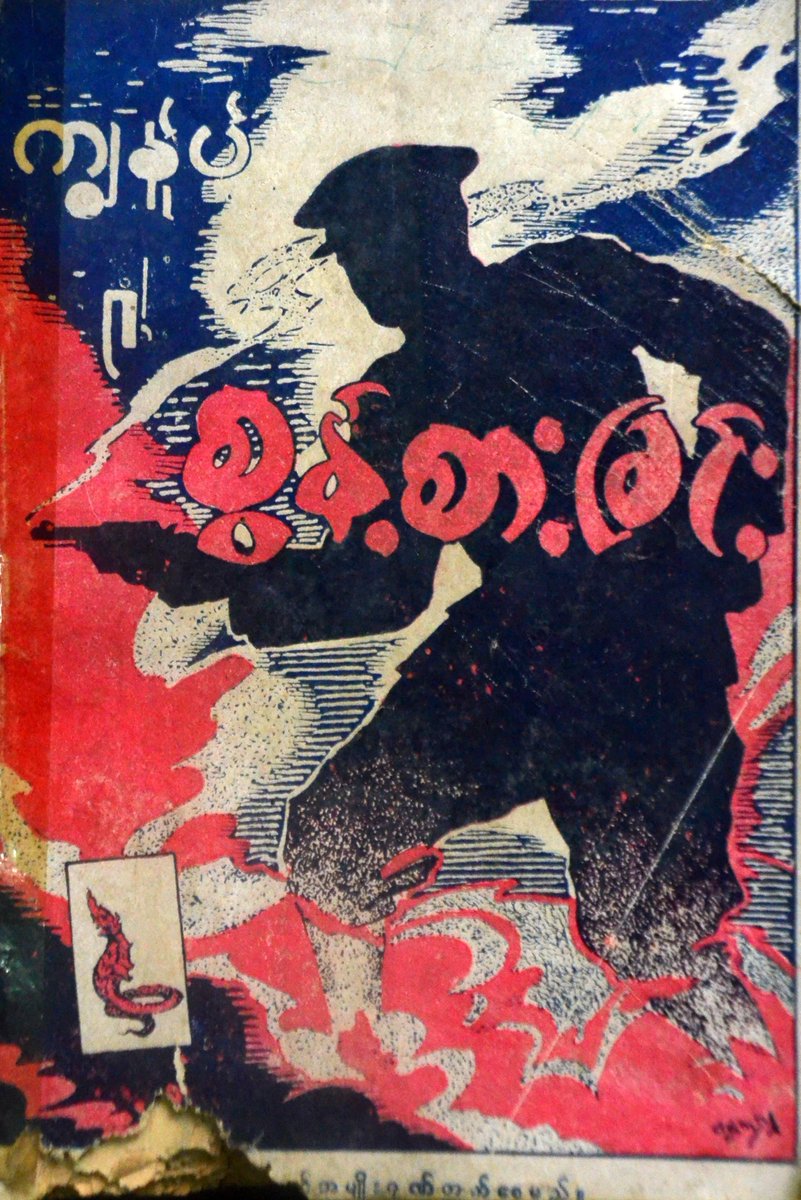

(Pic - Dan Breen in Burmese)

This history parallels the Irish in many ways.

(Pic - Dan Breen in Burmese)

When Dhammaloka was put on trial he was ofc supported by other Buddhist monks and the organised Buddhist laity, with a lawyer who would become a leading nationalist, U Chit Hlaing...

But he was also supported by "United Burma", a seditious paper owned by Gandhi's patron and fellow Congress radical PJ Mehta, who worked w the largely Indian and Muslim dockworkers of colonial Rangoon - whose pop was less than 50% Burmese.

On the day of his trial the Burmese and Indian bazaars closed and the crowds came to support him - as did the Chinese one (his monastery was in Chinatown and his ordination was sponsored by a Chinese merchant).

And we know that his connections also included other poor whites like ex-sailors and no doubt other ex-dockers like himself.

Before the rise of a more supremacist Burmese Buddhist nationalism, we see a multi-racial opposition to empire crystallising around this Irishman.

Before the rise of a more supremacist Burmese Buddhist nationalism, we see a multi-racial opposition to empire crystallising around this Irishman.

Today we are sometimes told that Irish participation in Empire was fine b/c it meant being part of the wider world.

But there were competing versions of that wider world - one holding bayonets to defend the court and one in the crowd constesting it.

But there were competing versions of that wider world - one holding bayonets to defend the court and one in the crowd constesting it.

Irish discourse is often *only* interested in what Irish ppl should have done to be good Irish ppl.

But from a genuinely international point of view, it also matters what Irish ppl did to other ppl and on whose behalf.

This is the history we all live with in so many ways.

But from a genuinely international point of view, it also matters what Irish ppl did to other ppl and on whose behalf.

This is the history we all live with in so many ways.

And the actual conquest, killing and repression of ppl *outside* Ireland ... had ethical components.

We can't pretend ppl at the time didn't know this. It was an insanely religious period in Ireland, and ppl had discourses on morals coming out of their ears.

We can't pretend ppl at the time didn't know this. It was an insanely religious period in Ireland, and ppl had discourses on morals coming out of their ears.

They editorialised at what seems to us like great length about their public actions.

And imperialism was contested "at home" as well as abroad - and not just in relation to Ireland.

You knew that these were ethical and political questions.

And imperialism was contested "at home" as well as abroad - and not just in relation to Ireland.

You knew that these were ethical and political questions.

It is more a late C20th and early C21st privatism that leads us to dismiss whatever ppl do in their job as irrelevant, while celebrating who occupies the jobs that send out the drones or let ppl die in the Mediterranean.

We can't impose our morals on theirs, etc.

We can't impose our morals on theirs, etc.

Anyway...

This may be news to the Irish Times, but Irish leftists have discussed the complexities of international anti-colonial solidarity for decades.

This may be news to the Irish Times, but Irish leftists have discussed the complexities of international anti-colonial solidarity for decades.

Literary scholars like Tadhg Foley and Maureen O'Connor have been writing about Irish-Indian links in this postcolonial vein for many years.

@ISASR_ colleagues have looked at how religion offered scope for anti-colonial solidarity in many contexts.

@ISASR_ colleagues have looked at how religion offered scope for anti-colonial solidarity in many contexts.

The Dhammaloka story has only just been published this year... https://global.oup.com/academic/product/the-irish-buddhist-9780190073084?cc=ie&lang=en

but "Buddhism and Ireland" covered much of the same ground back in 2013 - around a religion that spanned much of the British Empire in Asia. https://www.equinoxpub.com/home/buddhism-ireland/

Laurence Carroll / U Dhammaloka was by no means the only Irish person to be able to leap over a provincial ethnocentrism that only cared what happened on their home island ... and the global blindnesses of empire and whiteness.

It was entirely possible, in the late C19th and early C20th, to see the parallels between two parts of the British Empire in the same way colonial administrators did - and to respond with political solidarity, religious conversion, human connection - or all three.

And as Maurice Collis said about Luce (who was "cancelled" for marrying a Burmese woman),

"What he nourished and advanced, has prospered; what his detractors upheld has withered away."

"What he nourished and advanced, has prospered; what his detractors upheld has withered away."

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter