I'm really excited that this paper is finally out (+ open access). This was the main project I worked on for three years as a postdoc: trying to figure out what concepts are and how polysemy works.

Here's a thread ...

...

1/20 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mila.12328

Here's a thread

...

...1/20 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mila.12328

Fodor thought that concepts are atomic, i.e., unstructured. Most people in the literature think concepts are structured bodies of information. First I argue that, contra the consensus, Fodor was right -- we need conceptual atoms to compose and to unify diverse bodies of info. 2/

I criticize work from anti-atomists like Weiskopf and Vicente, but Vicente's work helped me recognize a devastating problem for Fodor: polysemy.

Fodor's idea was that a concept is (roughly) a pair: a particular atomic symbol together with its denotation. 3/

Fodor's idea was that a concept is (roughly) a pair: a particular atomic symbol together with its denotation. 3/

But polysemy suggests that concepts don't have unique denotations. E.g., 'bottle' can refer to a container or to the liquid that fills it, even in one sentence: "Jane drank the bottle and smashed it."

The concept BOTTLE seems to shift its denotation freely. 4/

The concept BOTTLE seems to shift its denotation freely. 4/

Fodor thought that polysemy was really a form of homonymy, like how 'ruler' can refer to a monarch or a measuring tool, plus a sense of relatedness.

But I review experimental evidence that polysemy really does involve a single word meaning like BOTTLE + multiple denotations. 5/

But I review experimental evidence that polysemy really does involve a single word meaning like BOTTLE + multiple denotations. 5/

Some of the evidence comes from psycholinguistics, especially the work of Klepousniotou.

I won't walk through specifics here, but the upshot is that homonyms like 'ruler' compete, slowing + inhibiting each other. Polysemes like 'bottle' instead share a common representation. 6/

I won't walk through specifics here, but the upshot is that homonyms like 'ruler' compete, slowing + inhibiting each other. Polysemes like 'bottle' instead share a common representation. 6/

Other evidence comes from developmental psychology. Kids with little metalinguistic ability learn novel words and freely, spontaneously extend them in polysemy-like ways. This doesn't happen for homonyms. Much of the work here is done by Srinivasan, @hugh_rab, and Snedeker. 7/

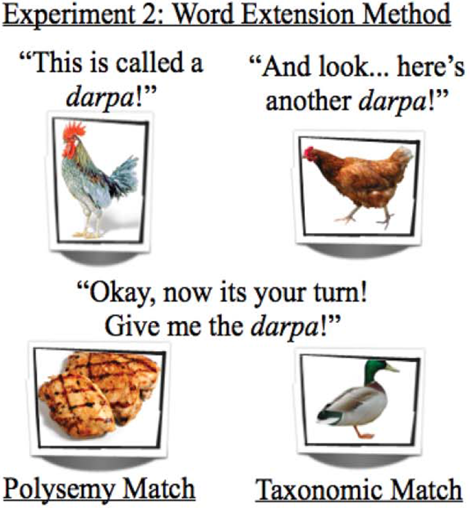

Here's an example from Srinivasan & Snedeker (2014). Kids hear the word 'darpa' paired with a chicken twice, and then have to choose to apply it to a duck (visually + taxonomically similar) or grilled chicken (dissimilar but linked through polysemy). They apply it to the meat. 8/

This result is so interesting partly bc the kids are violating known principles of word learning, such as the "shape bias" and "taxonomic constraint" (apply the word to similarly shaped + taxonomized objects, respectively).

Polysemy overrules them. 9/ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15475441.2013.820121

Polysemy overrules them. 9/ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15475441.2013.820121

Again, findings like this don't hold for homonyms. Mapping a novel word to (baseball) bats doesn't cause kids to extend it to (flying mammalian) bats.

Nor are these effects due to association/relatedness. A novel word mapped to CHICKEN doesn't extend to EGG. 10/

Nor are these effects due to association/relatedness. A novel word mapped to CHICKEN doesn't extend to EGG. 10/

It looks like polysemy is real: a semantic representation in a single lexical entry is used to achieve distinct, often highly dissimilar denotations.

It seems therefore that lexical concepts like CHICKEN and BOTTLE don't work the way Fodor thought. 11/

It seems therefore that lexical concepts like CHICKEN and BOTTLE don't work the way Fodor thought. 11/

One might respond at this point that semantic representations (the things we use to grasp word meanings) are not concepts (the things we use to think + categorize). This idea is increasingly widespread. But I argue in the paper that the empirical evidence leans against it. 12/

So what are concepts, then?

I argue that while Fodor was wrong about the semantic properties of concepts, he was right about their internal structure. Concepts are unstructured atoms, but they don't have unique denotations. 13/

I argue that while Fodor was wrong about the semantic properties of concepts, he was right about their internal structure. Concepts are unstructured atoms, but they don't have unique denotations. 13/

Atomism faces the charge that unstructured concepts don't explain how cognition unfolds.

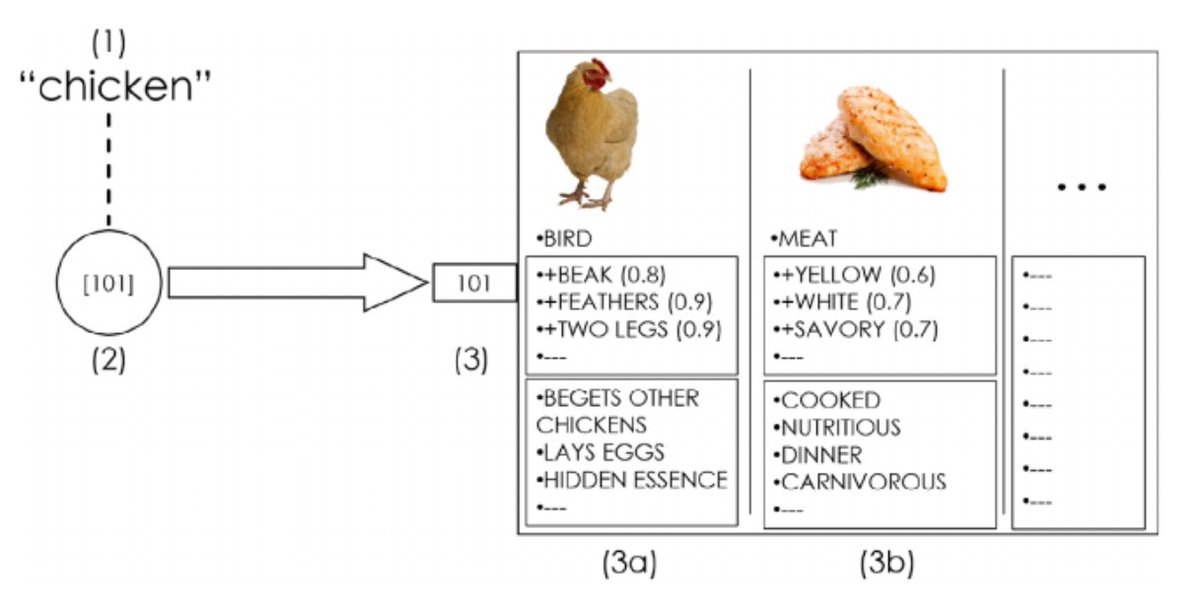

I argue that concepts are "pointers" to memory locations containing diverse bodies of info (prototypes, theories...). Atomic concepts can thus usefully guide the stream of thought. 14/

I argue that concepts are "pointers" to memory locations containing diverse bodies of info (prototypes, theories...). Atomic concepts can thus usefully guide the stream of thought. 14/

Combining this idea with insights from polysemy, I argue that concepts are "generative pointers."

That is, they fail to fix a denotation, but instead make available bodies of info that may be deployed to modulate the denotation of a particular occasion of use. 15/

That is, they fail to fix a denotation, but instead make available bodies of info that may be deployed to modulate the denotation of a particular occasion of use. 15/

For example, here's what the concept CHICKEN might look like.

You have an unstructured concept that points to a location where info about birds and meat are stored. When you hear 'delicious chicken', you might retrieve info about chicken-qua-meat, not chicken-qua-bird. 16/

You have an unstructured concept that points to a location where info about birds and meat are stored. When you hear 'delicious chicken', you might retrieve info about chicken-qua-meat, not chicken-qua-bird. 16/

One part of this story, borrowed/tweaked from Relevance Theory (especially Carston) and a paper by @danielwharris, is that the semantic significance of a concept is not a denotation but a constraint on denotations achievable through its deployment. 17/ https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12290

The "generative pointer" idea allows us to make sense of the role of concepts in (1) compositional thought, (2) lexical meaning, + (3) reasoning.

Many theories minimize or give up on one of these: 1 bc bodies of info may not compose, 2 bc of polysemy, 3 bc of atomism. 18/

Many theories minimize or give up on one of these: 1 bc bodies of info may not compose, 2 bc of polysemy, 3 bc of atomism. 18/

The idea of generative pointers raises other possibilities, such as unresolved ambiguity in thought.

I think this is actually intuitive. E.g., I think you can think a thought like THERE IS A SEAT BY THE DOOR without resolving the ambiguity in 'door' (barrier vs. aperture). 19/

I think this is actually intuitive. E.g., I think you can think a thought like THERE IS A SEAT BY THE DOOR without resolving the ambiguity in 'door' (barrier vs. aperture). 19/

It also provides a way of making sense of recent work on concepts, including "dual-character" concepts ( https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2013.01.005) and conceptual engineering.

These shifts in conceptual denotations make sense if concepts are generative pointers.

Thanks for reading! 20/20

These shifts in conceptual denotations make sense if concepts are generative pointers.

Thanks for reading! 20/20

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter