Our publication in @ELSenviron, about invasive hippo persistence and dispersal in the Magdalena River basin on #Colombia, has just come out. The following thread summarizes our results.

@postre_de_natas @juvelas @Rafael_MorenoA @jwmorenob @donsabas

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320720309812?dgcid=author

@postre_de_natas @juvelas @Rafael_MorenoA @jwmorenob @donsabas

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0006320720309812?dgcid=author

As many of you may already know, hippos were introduced in Colombia during the 1980s by drug lord Pablo Escobar. Since that moment, the population has been growing. Control measurements have not been successful, and there is no clarity on future strategies.

As some of us had previously told here on twitter, hippos can be horribly harmful for ecosystems in the Magdalena river basin. https://twitter.com/Iamguichaves/status/1265309952542998530

Hippos are extremely aggressive, territorial animals, dangerous for people close to rivers, and affecting access to fishing resources. A farmer was seriously injured by a hippo this year, it is only a matter of time before another attack takes place. http://cutt.ly/4yb0j8L

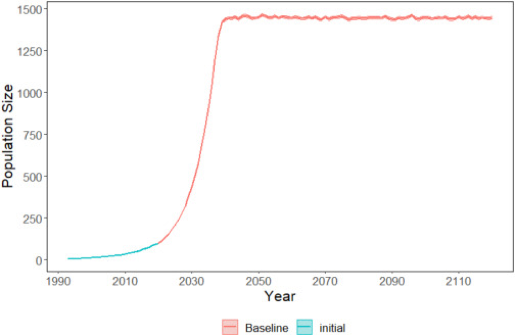

We wanted to contribute from our experience with some analyses that may hopefully enrich the debate. We started by estimating how many hippos may be currently inhabiting the Magdalena river basin. The situation is not very encouraging.

We calculated that there should be approximately 100 invasive hippos (where the blue line ends) and if further actions are not taken, the hippo population may reach almost 1500 individuals in 2034 (red line).

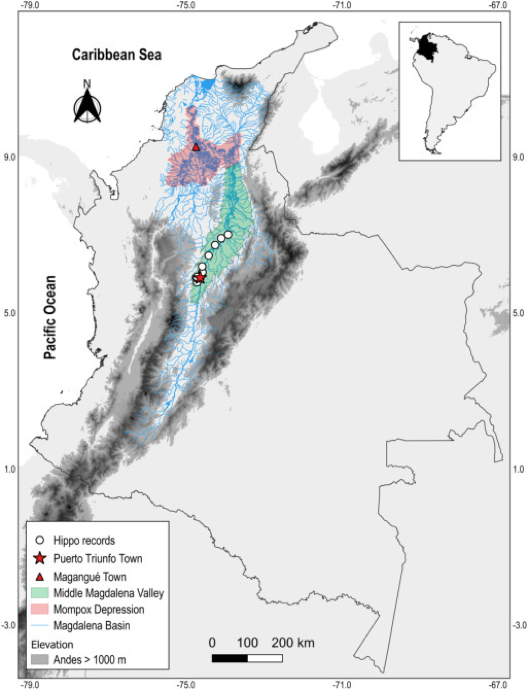

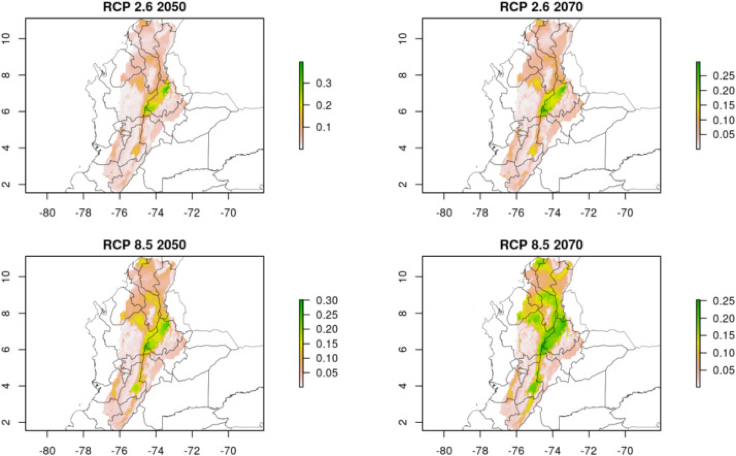

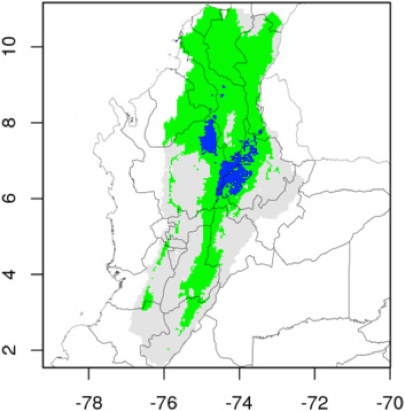

In addition, we decided to use ecological niche modelling to estimate the current area occupied by hippos in the Magdalena basin, as well as future dispersal trends, under future climate change scenarios.

In this map we can see in blue the current occupation area, in green the potential occupation area, and in gray those areas not susceptible of being occupied.

What does this mean? if introduced hippos are not controlled, the invasion will reach the marshy region in the northern Magdalena basin. This would jeopardize the ecosystem integrity and biodiversity, as well as physical and food security for thousands of farmers and fishers.

Our models show a hippo growth population of about 14.5% (far higher than most African hippo populations), and very high rates of geographical dispersal, with will be also favored by climate change.

What makes this invasive population more successful than its African relatives? The most likely explanation is that in Africa hippos are controlled by natural predators (lions, Nile crocodiles), disease, extreme drought, and hunting.

In the Magdalena basin, hippos have no predators, the system offers unlimited resources, drought is never very drastic, and there is no control by humans. Because of this, territorial and mate competition is also low, allowing for precocious and successful reproduction.

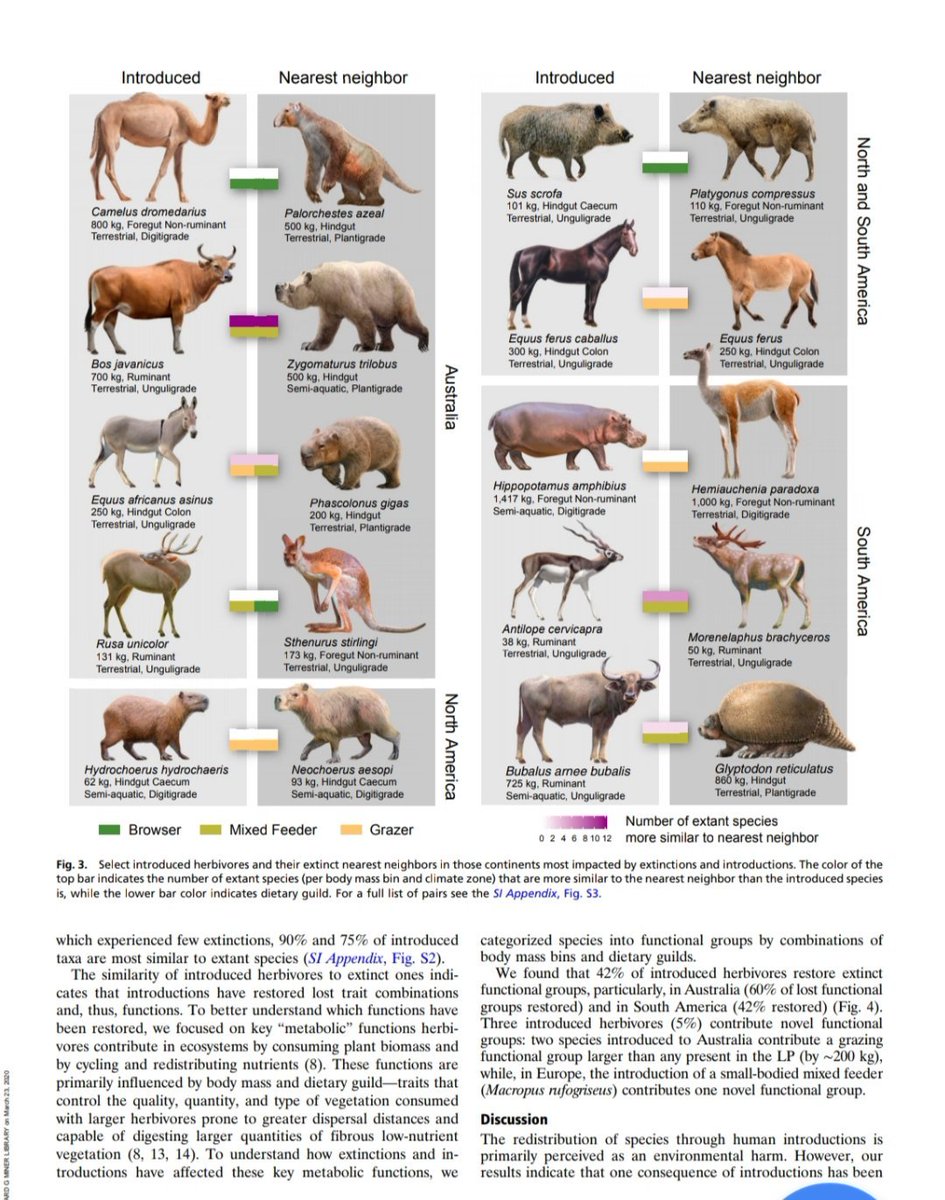

There has been some discussion on possible ecological and social advantages of the presence and growth of the hippo population in Colombia. It has been said, for example, that hippos would be supplying the ecological niche of extinct Pleistocene toxodonts.

However, morphological and isotopic studies of toxodonts indicate that they were terrestrial rather than semiaquatic. In the Magdalena basin there are mammals occupying the large aquatic or semiaquatic herbivore niche, such as the West Indian manatee or the lesser capybara.

Then, rather than a path for ecosystem restoration, invasive hippos may in fact displace and affect Colombian native mammals (several of them endangered) that are already occupying those niches, leading to species loss and ecological imbalance.

Introduced hippos have also been considered a “genetic reservoir”. However, the original group was only 1 male and 3 females, so we expect low genetic diversity and high endogamy (inbreeding). These conditions make Colombian hippos unsuitable for repopulation programs.

In conclusion, we consider that the population of invasive hippos must be controlled and extirpated in order to avoid a series of cascading ecological and social events, disastrous for the Magdalena river Basin and its inhabitants. But, how to do this?

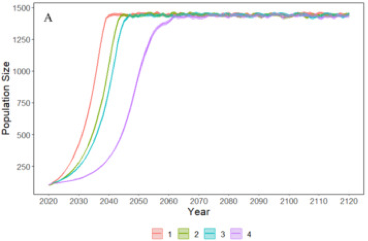

We decided to model how the population would grow if we take different control measurements. We first tried with castration or sterilization of individuals, at different levels (from 6 to 16 individuals per year). This is what we obtained:

None of the castration strategies will be enough to control the population. Castration would only delay the moment in which the population reaches the loading capacity, that is, the year in which the maximum possible number of hippos is reached.

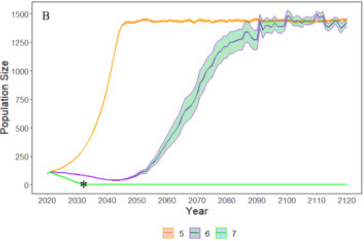

Then we tried to introduce an extraction strategy (controlled hunting or capture-relocation), at several levels (10, 20, and 30 individuals per year).

Only the highest level of extraction (15 males + 15 females) would eradicate the hippo population in Colombia (light green line).

We understand that the extraction strategy is the eye of the storm of the current debate in Colombia. However, we suggest to consider reviewing the law that currently forbids controlled hippo extraction.

Strategies such as castration/sterilization, containment in confined areas, and captivity, would also be useful as a complement to euthanizing efforts, but castration and relocation won’t be enough on their own @yeyorojano https://elrazonante.com/2020/06/03/hipopotamos-en-el-rio-magdalena-podemos-mantenerlos-bajo-cuidado-humano/

Our models are theoretical and predictive, we insist that fast, intensive scientific monitoring of this invasive population must be done. We propose to use drones, environmental DNA, camera traps, and others to have a scientific information basis in order to take proper action.

Thank you very much for reading all the way down to this point, we appreciate if you help us sharing this information. You can access the paper here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347928073_A_hippo_in_the_room_Predicting_the_persistence_and_dispersion_of_an_invasive_mega-vertebrate_in_Colombia_South_America

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter