A Sunday evening thread on the early twentieth century British debate on free trade vs tariffs and why it might be relevant to the Brexit debate.

You can stretch supposed economic parallels until they break. But I want to talk about politics instead.

You can stretch supposed economic parallels until they break. But I want to talk about politics instead.

There’s been a lot of discussion on whether British politics can now “move on” from Brexit.

I have no idea. Certainly our trading relationship with Europe will still matter a great deal. But the issue might fade from politics. This is where the early twentieth century is useful

I have no idea. Certainly our trading relationship with Europe will still matter a great deal. But the issue might fade from politics. This is where the early twentieth century is useful

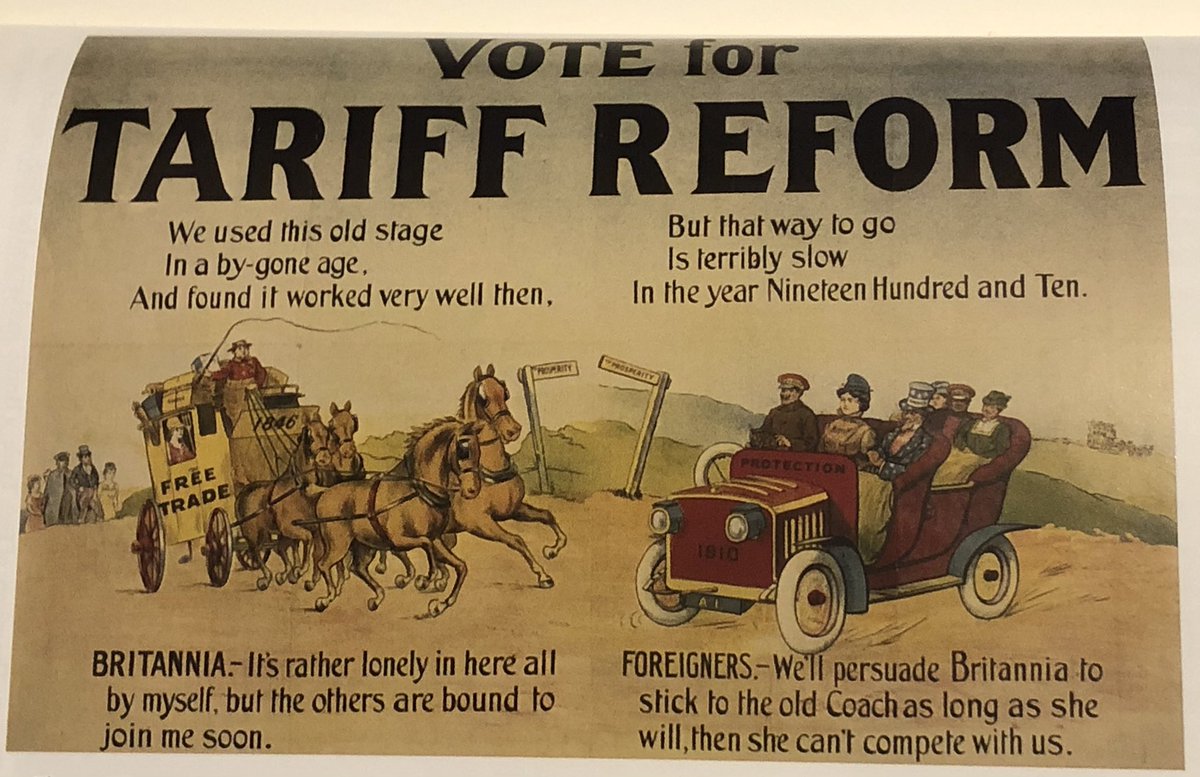

In the first few decades of the 20th century free trade vs tariffs was a huge issue in British politics. It dominated some elections (1906 & 1923) and bubbled along as a major factor in all the others.

Britain had dropped tariffs in the 1840s and embraced free trade. That fight (which is another story) has been won narrowly by the Free Traders in terms of Parliamentary votes but totally in terms of the impact for the next few decades.

But by 1900, Britain’s political economy had begun to shift. In the 1840s the leading defenders of tariffs had been the (politically extremely powerful) agricultural or landed interest. Free trade had united industrial, commercial and working interests.

But while Britain had about a 45% of global manufactured goods exports in the 1840s, that had slipped to a (still high) 30% by 1900. Industrialisation had spread and Britain had more competitors.

Ernest Williams’s diatribe Made in Germany was a best seller in 1896. Some industrialists were starting to see the appeal in tariff protection. Enter Joe Chamberlain.

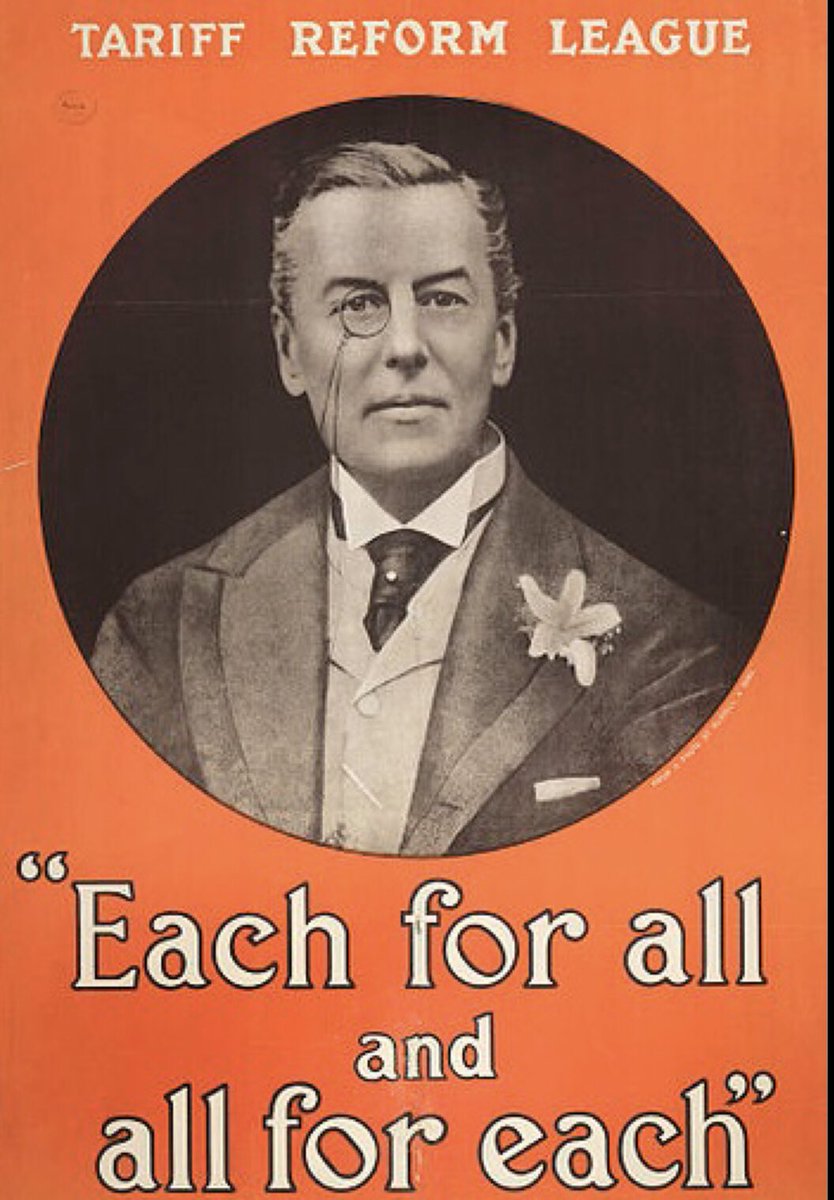

Chamberlain will achieve the rare distinction of splitting not one but two political parties. Having already caused a split in the Liberal Party, over the issue of Irish Home Rule, he’ll split the Tories over tariffs in the early 1900s.

Chamberlain argued for tariffs on three grounds: they would protect British industry and jobs from “unfair” competition, they would bind the Empire closer together and they would raise revenues that could be spent on social reform.

Chamberlain was persuasive. The Tories moved to backing tariffs (usually called Tariff Reform) leading to many leading Tories either leaving politics altogether or defecting to the Liberals (as a young MP called Winston Churchill did).

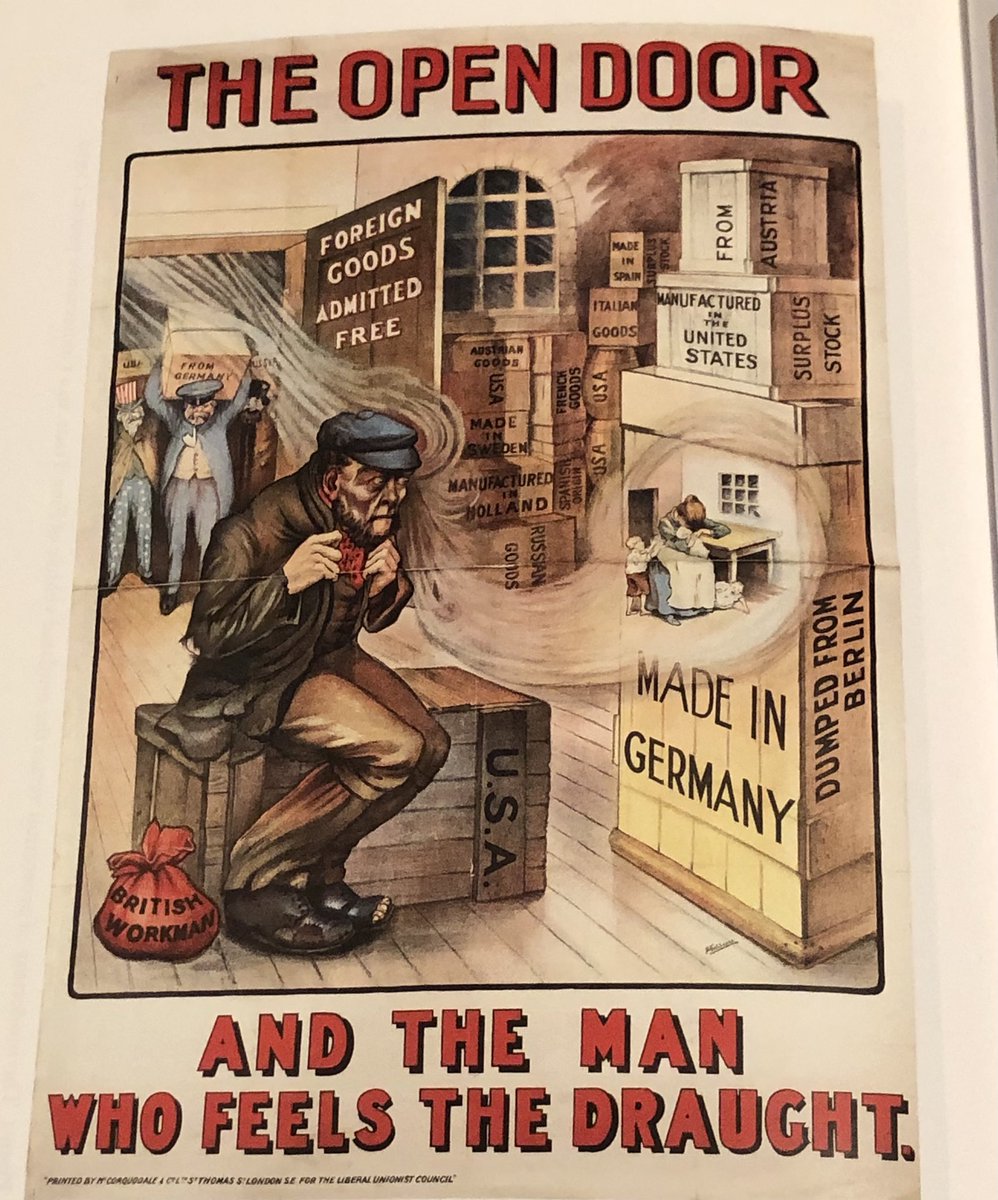

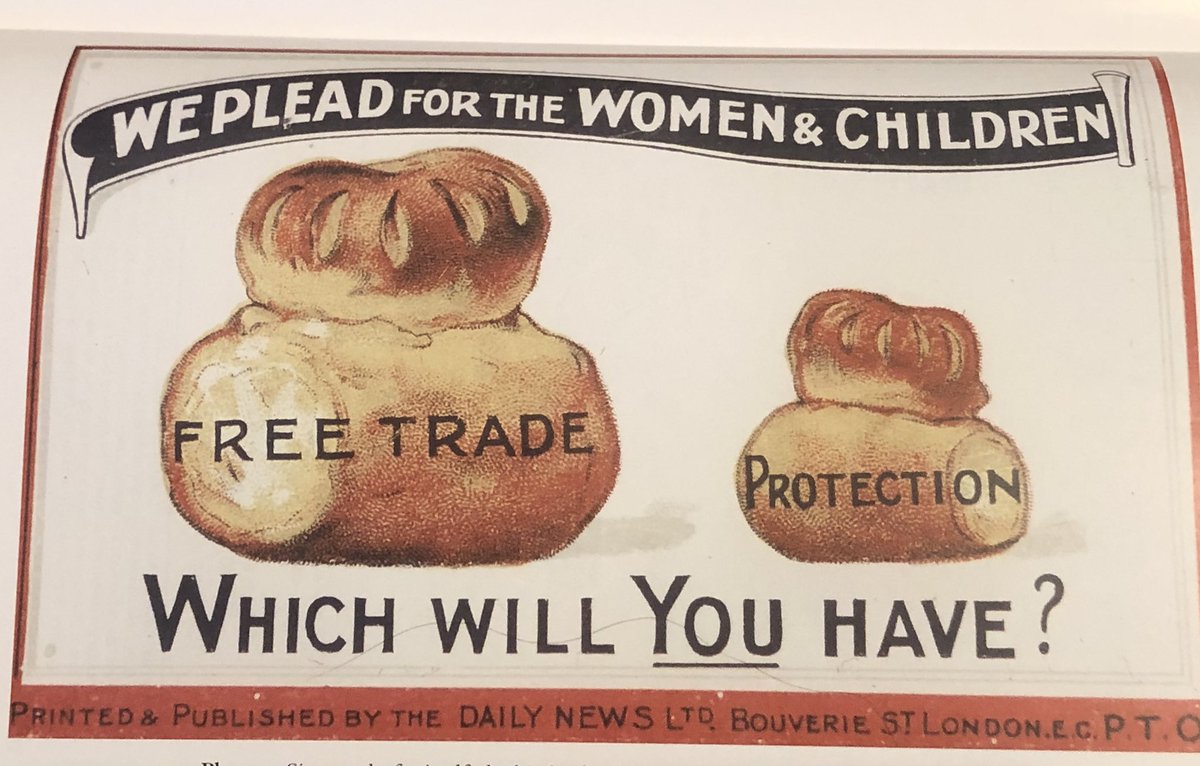

While the case for tariffs focussed on manufacturing and industrial jobs, the free traders focussed instead on food.

The “big free trade loaf” was their preferred visual. Tariffs would raise the cost of the necessities of life and impoverish workers they argued.

The “big free trade loaf” was their preferred visual. Tariffs would raise the cost of the necessities of life and impoverish workers they argued.

Some went as far as to suggest the German taste for black bread and horse flesh was a result of their tariff wall rather than dietary preferences. “Vote for tariffs and we’ll end up eating smelly sausages and horses”.

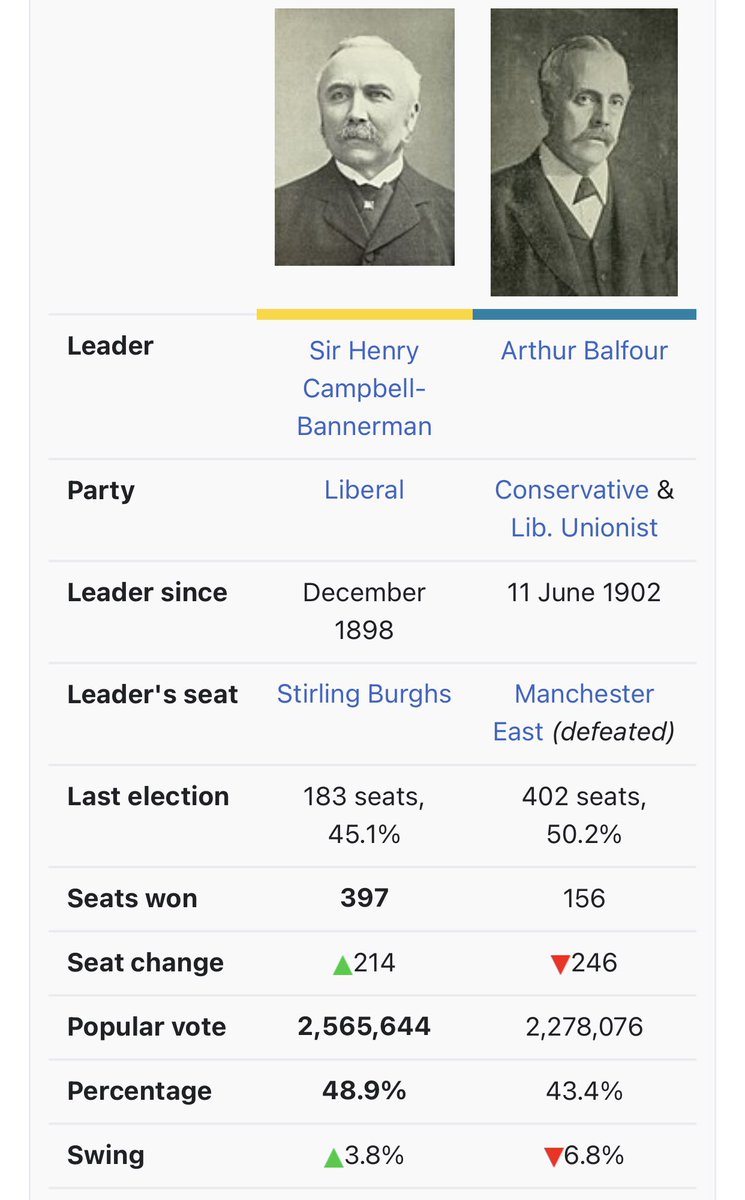

Backing tariffs in 1906 was a factor in the Conservatives suffering a landslide defeat. But the issue didn’t die.

As the Liberals embarked on building a slightly larger state with unemployment insurance and modest old age pensions in the decade before the First World War, taxes had to be raised. The potential of tariffs as an alternative source of funding provided a much used Tory argument.

The Great War McKenna duties were the start of a retreat from free trade. After the war, politics was realigning. The Safeguarding of Industry Act 1921 moved further towards protectionism. But the basis of international trade policy was still mostly aligned with free trade.

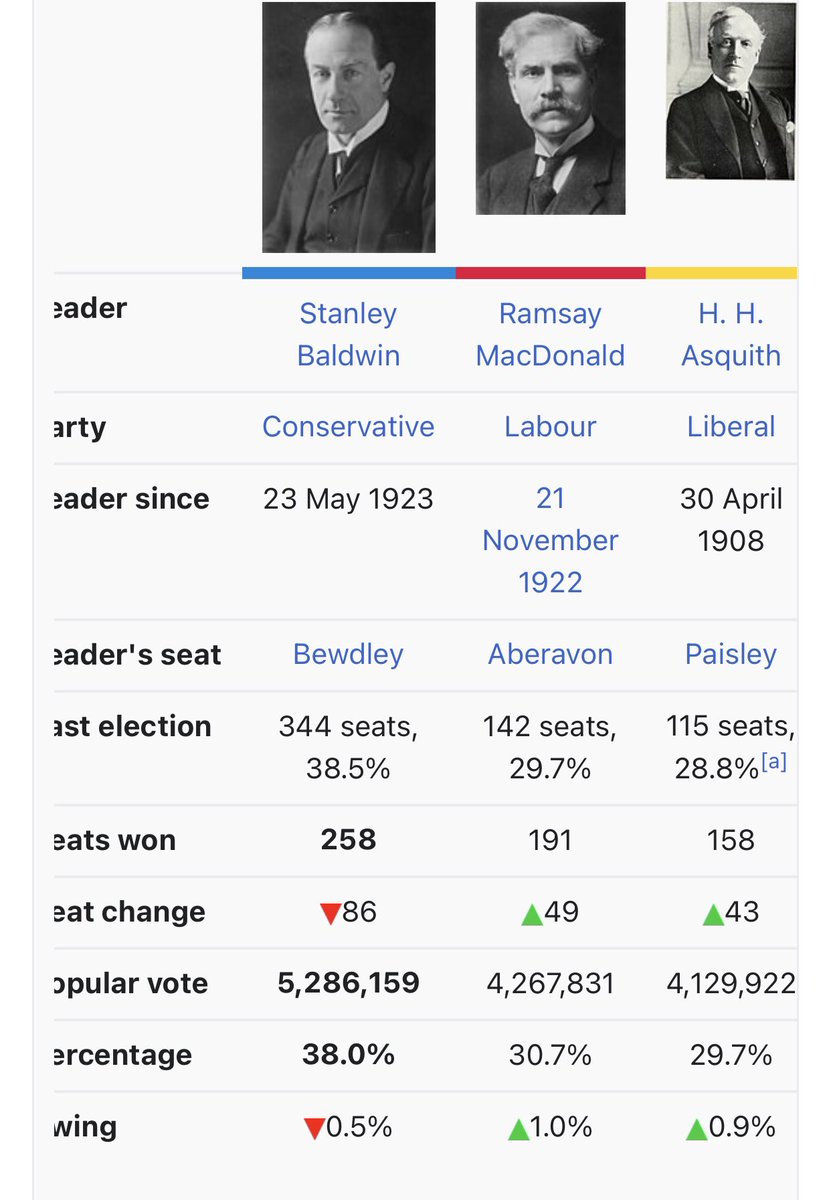

Baldwin’s attempt to win a mandate for further tariffs in 1923 was a disaster for his party and resulted in the messiest general election result of the 20th century.

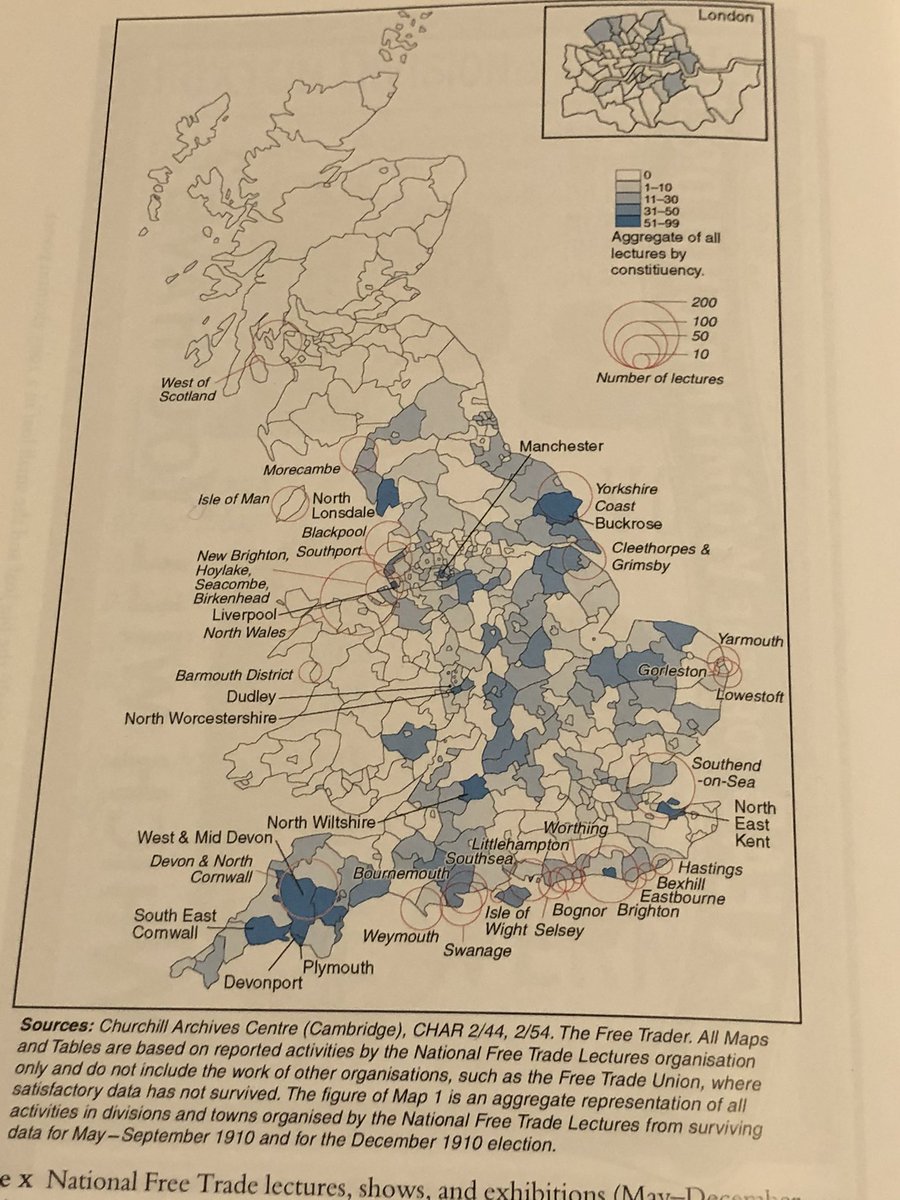

But while the electorate might not be convinced, tariff reform - by now mainly rebranded as Imperial Preference (trade discrimination in favour of the Empire) was very much a live issue for the right. Fanned by Lord Beaverbrook’s Daily Express.

The Labour Party of the 1920s was emerging as the second party. The party constitution of 1918 contained Clause 4 but while the party might be officially socialist, it was also committed to free trade.

MacDonald and Snowden were as Gladstonian in their trade views as on balanced budgets. Indeed Snowden, Labour’s first chancellor, stuck with the national government over cutting the dole but resigned when it introduced tariffs.

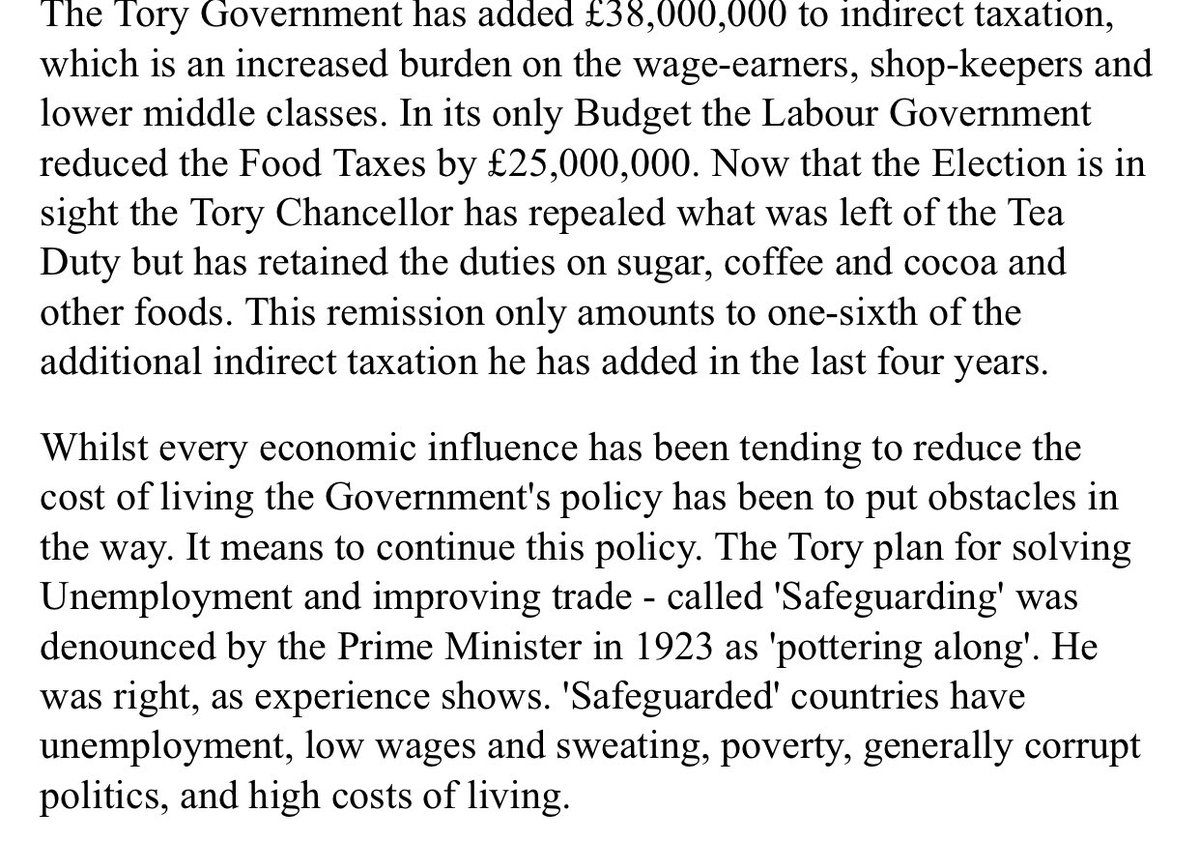

The Party’s manifesto when it won the 1929 election was damning on the Tories trade policies of the late 1920s. Tariffs were simply “indirect taxation” that hit workers. Safeguarding didn’t work.

But, after the formation of the Tory dominated National Government in 1931, amid a sweeping economic crisis, protectionism won.

Neville Chamberlain as Chancellor, Joe’s son, got to fulfil his father’s dream.

Labour’s 1931 manifesto was firmly anti-tariff.

Neville Chamberlain as Chancellor, Joe’s son, got to fulfil his father’s dream.

Labour’s 1931 manifesto was firmly anti-tariff.

But the national government won by a landslide. And got to work on dismantling free trade.

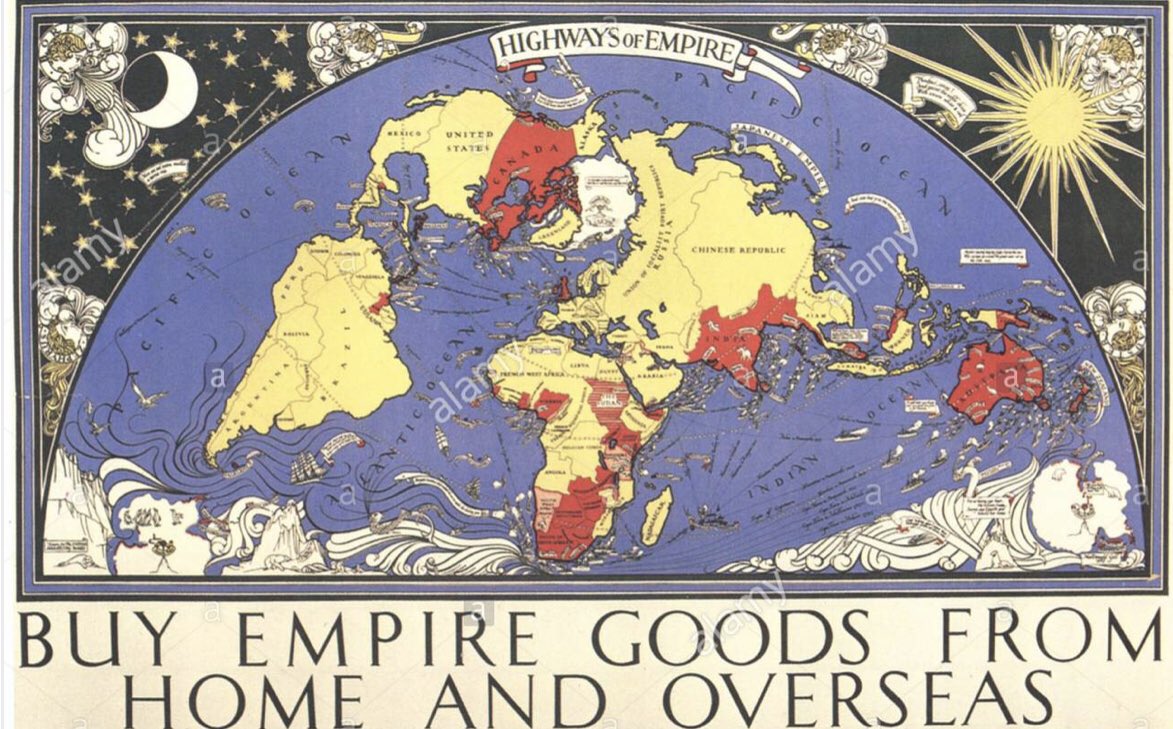

Discriminatory tariffs favoured imperial producers and advertising campaigns urged consumers to buy empire goods.

Discriminatory tariffs favoured imperial producers and advertising campaigns urged consumers to buy empire goods.

By 1935, the issue was absent from Labour’s manifesto. Tariffs had won. A central dividing line in British politics for three decades was essentially shelved in a way that would have amazed anyone involved between 1900 and 1930.

Political economy divides change over time.

Political economy divides change over time.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter