I got the Criterion Edition for Christmas, so...

#NowWatching “The Irishman.”

I think it fits nicely with the ambiance of this time of year. It’s a film you sit with and digest.

#NowWatching “The Irishman.”

I think it fits nicely with the ambiance of this time of year. It’s a film you sit with and digest.

“Get that fixed, because it’ll go again on you.”

I love how “The Irishman” spends like half-an-hour on metaphors before the plot actually starts.

In that Frank’s moral decline happens like the wearing of his truck’s engine. It happens gradually, from lack of maintenance.

I love how “The Irishman” spends like half-an-hour on metaphors before the plot actually starts.

In that Frank’s moral decline happens like the wearing of his truck’s engine. It happens gradually, from lack of maintenance.

It’s also reflected neatly in the way that Frank steals the cuts of beef from the truck he’s driving.

He takes a couple of cuts at a time. Nobody notices, it pays well. Then a couple more. Nobody notices, it pays well.

Before you know it, everything is gone.

He takes a couple of cuts at a time. Nobody notices, it pays well. Then a couple more. Nobody notices, it pays well.

Before you know it, everything is gone.

This is something that recurs in Scorsese’s films.

You transgress. You get away with it. You rationalise. You transgress further.

Every transgression takes a little of your soul, and every time the bit of your soul taken gets a little bigger.

And before you know, it’s gone.

You transgress. You get away with it. You rationalise. You transgress further.

Every transgression takes a little of your soul, and every time the bit of your soul taken gets a little bigger.

And before you know, it’s gone.

“It's crazy, but I never understood how they would just keep digging their own graves. Maybe they thought if they do a good job, the guy with the gun would change his mind.”

Before Frank’s journey with Russell has begun, “The Irishman” has already told the story in miniature.

Before Frank’s journey with Russell has begun, “The Irishman” has already told the story in miniature.

People complained about the length of “The Irishman”, but the film uses its length in a variety of ways. It often feels like something of a folktale or a myth.

It’s a morality play in which the stakes and the arc are plotted well in advance. It’s evident where this going.

It’s a morality play in which the stakes and the arc are plotted well in advance. It’s evident where this going.

Indeed, it’s notable in a very “this is what the movie is doing” way that “The Irishman” opens with Frank charting a course that we’ll spend the movie watching him follow.

Again, it’s all very lyrical and reflective. It’s a very confident bit of storytelling.

Again, it’s all very lyrical and reflective. It’s a very confident bit of storytelling.

“When I ask somebody to take care of something for me, I expect them to take care of it themselves. I don't need two roads coming back to me.”

Again, “The Irishman” comes back time and time again to the idea of “roads”, both literal and metaphorical.

Again, “The Irishman” comes back time and time again to the idea of “roads”, both literal and metaphorical.

The road is obviously a metaphor for the path of Frank’s life. Frank spends much of “The Irishman” convinced that he has no choice - that, to quote Russell, once you get on the highway “they don’t let you stop.”

This becomes a self-rationalisation or -justification.

This becomes a self-rationalisation or -justification.

This is interesting, because it distinguishes Frank from obvious points of comparison in the Scorsese canon like Henry Hill or Jordan Belfort.

Hill and Belfort are defined by wants and needs, by desire and by ambition. They do terrible things because they like the power.

Hill and Belfort are defined by wants and needs, by desire and by ambition. They do terrible things because they like the power.

If anything, Frank is probably closest to Ace Rothstein from “Casino”, at least as Ace is introduced.

Ace is introduced as a vehicle for others, a representative of the mob bosses, an embodiment of the lifestyle.

Ace is just a cog in the machine, initially.

Ace is introduced as a vehicle for others, a representative of the mob bosses, an embodiment of the lifestyle.

Ace is just a cog in the machine, initially.

As Ignatiy Vishnevetsky pointed out, the signature shot from “Casino” is a point of view shot from the perspective of a nostril inhaling cocaine.

Ace is just the straw, even if he eventually gets swept up in the glamour of it. But he’s not an ambitious man. He just goes along.

Ace is just the straw, even if he eventually gets swept up in the glamour of it. But he’s not an ambitious man. He just goes along.

Frank in “The Irishman” reminds me a lot of Ace, a moral vacuum in the shape of a man. He has no ambition or integrity of his own.

He is just a vehicle through which others’ ambition flows. He believes this absolves him of responsibility, as he believes he never made a choice.

He is just a vehicle through which others’ ambition flows. He believes this absolves him of responsibility, as he believes he never made a choice.

This is one of the ways in which “The Irishman” feels like an evolution of Scorsese’s approach to these themes.

Films like “Goodfellas”, “Casino” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” were accused of glamourising these people, but it’s hard to imagine anyone *wanting* to be Frank.

Films like “Goodfellas”, “Casino” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” were accused of glamourising these people, but it’s hard to imagine anyone *wanting* to be Frank.

Of course, “The Irishman” argues that this lack of moral agency is a sin of itself.

Frank is just as culpable for the choices he never made, for refusing to exert the moral agency that elevates men above animals.

It’s a logical endpoint for this theme in Scorsese’s films.

Frank is just as culpable for the choices he never made, for refusing to exert the moral agency that elevates men above animals.

It’s a logical endpoint for this theme in Scorsese’s films.

“Russell and Carrie baptized our new daughter, Dolores. It was a wonderful occasion, and we were honored.”

In charting “The Irishman” as the culmination within Scorsese’s filmography, it’s interesting that the film brings his gangster films full circle with “The Godfather.”

In charting “The Irishman” as the culmination within Scorsese’s filmography, it’s interesting that the film brings his gangster films full circle with “The Godfather.”

While the mob was present in Scorsese’s earliest work, especially his shorts like “It’s Not Just You, Murray”, many critics agree that the theme only really came to the fore in “Mean Streets.”

“Mean Streets” came out the same year as “The Godfather.”

“Mean Streets” came out the same year as “The Godfather.”

Notably, “Goodfellas” came out the same year as (competed for the Best Picture Oscar against and featured Catherine Scorsese) like “The Godfather, Part III.”

However, “Goodfellas” was seen as the future of the gangster genre, and “The Godfather, Part III” as a relic of its past.

However, “Goodfellas” was seen as the future of the gangster genre, and “The Godfather, Part III” as a relic of its past.

However, “The Irishman” borrows very overtly and very directly from the “Godfather” films, done to particular shots, story choices with Frank and Jimmy, and historical details around Kennedy and Cuba.

It feels like Scorsese making his peace with the films, reconciling with them.

It feels like Scorsese making his peace with the films, reconciling with them.

It feels appropriate that “The Godfather, Coda” was released within a year of “The Irishman.”

One of Coppola’s biggest changes to was to alter the ending in such a way that it feels like a deliberate echo of “The Irishman”, which at times feels like an echo of “The Godfather.”

One of Coppola’s biggest changes to was to alter the ending in such a way that it feels like a deliberate echo of “The Irishman”, which at times feels like an echo of “The Godfather.”

“I mean, he’s a loyal guy, I’m sure. He’s a nice guy, but he ain’t that sharp. He ain’t that smart. He plays a lot of fucking golf, you know.”

“He plays golf? So what? That’s what you want from a number two. You don’t want somebody too smart.”

Frank, never the most self-aware.

“He plays golf? So what? That’s what you want from a number two. You don’t want somebody too smart.”

Frank, never the most self-aware.

“Are you looking at my ears?”

“Your ears? No.”

“I had an operation, so there’s no need for anyone looking at my ears anymore.”

Notably, Scorsese declines to preface “The Irishman” with a title card like “Goodfellas” or “Casino” credited those films to “true stories.”

“Your ears? No.”

“I had an operation, so there’s no need for anyone looking at my ears anymore.”

Notably, Scorsese declines to preface “The Irishman” with a title card like “Goodfellas” or “Casino” credited those films to “true stories.”

Instead, “The Irishman” feels like a twisted alternate history of the United States, only fleetingly intersecting with documented history - Bay of Pigs, the Missile Crisis, Kennedy assassination, Watergate.

It’s like “The Godfather” or “JFK”, a parallel “secret” history.

It’s like “The Godfather” or “JFK”, a parallel “secret” history.

Since it was first published, historians have repeatedly cast doubt (to put it mildly) on Frank Sheeran’s memoirs. However, “The Irishman” never feels like it’s trying to present itself as “real history.”

Instead, it’s like a trip into the nation’s dark and murky subconscious.

Instead, it’s like a trip into the nation’s dark and murky subconscious.

With the conspiratorial underpinnings of “The Irishman”, which pretty much says that the mob killed John F. Kennedy, the film reminds me a lot of the spooky alternate history of the United States in “The X-Files.”

(In particular, “Musings of a Cigarette-Smoking Man.”)

(In particular, “Musings of a Cigarette-Smoking Man.”)

“What? Rickles is the only one who can make jokes?”

In keeping with that postmodernist approach, “The Irishman” is a very self-aware piece of work, with Scorsese repeatedly playing on his own iconography.

Don Rickles appeared in “Casino”, but is a character here.

In keeping with that postmodernist approach, “The Irishman” is a very self-aware piece of work, with Scorsese repeatedly playing on his own iconography.

Don Rickles appeared in “Casino”, but is a character here.

Indeed, history and fiction blur and overlap in “The Irishman”, with Joe Pesci’s voiceover directing Frank to meet a character that Joe Pesci had played in “JFK.”

“The Irishman” assumes that the audience is literate enough to pick up on these sorts of layers.

“The Irishman” assumes that the audience is literate enough to pick up on these sorts of layers.

Adding to that layering of fiction and reality, it’s notable that “The Irishman” depicts the assassination of Joe Columbo at the behest of Joe Gallo, which almost derailed production of “The Godfather.”

Which seemed to then echo into “The Godfather, Part II” and “Part III.”

Which seemed to then echo into “The Godfather, Part II” and “Part III.”

It’s an interesting and deliberate blurring of reality, the fiction it shapes, the fiction that borrows from that reality, in turn influencing subsequent depictions of that real event.

It’s a fascinating hall of mirrors at play in “The Irishman.”

It’s a fascinating hall of mirrors at play in “The Irishman.”

There’s something fascinating in the density of all of this, compacting and contorting on top of itself.

“The Irishman” is in many ways a very traditional narrative and a very classical film. However, it’s also a very modern film despite that traditional sensibility.

“The Irishman” is in many ways a very traditional narrative and a very classical film. However, it’s also a very modern film despite that traditional sensibility.

This is obvious in the de-ageing technology and that it is a $200m movie from a streaming service that will be (despite Scorsese’s concerns) watched on laptops and phones.

But I think it’s also evident in the film’s reflexivity, reflecting the way we consume media today.

But I think it’s also evident in the film’s reflexivity, reflecting the way we consume media today.

One of the most interesting things about Scorsese, and probably why he’s endured better than any other Movie Brat except maybe Spielberg, is that he has always managed to keep up with the times around him.

This is particularly obvious with his 21st century work.

This is particularly obvious with his 21st century work.

On a practical level, think of how Scorsese has been able to keep making movies at his level. First by moving from studios to independent financiers, then going to streaming.

Think of Scorsese embracing 3D on “Hugo” or the energy and verve of “The Wolf of Wall Street.”

Think of Scorsese embracing 3D on “Hugo” or the energy and verve of “The Wolf of Wall Street.”

When I watch “The Irishman”, I think of the argument from Scorsese’s collaborator Paul Schrader that modern audiences have been exposed to more media - in more forms - than any prior generation.

And, as such, they understand stories in a different way. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jun/19/paul-schrader-reality-tv-big-brother

And, as such, they understand stories in a different way. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jun/19/paul-schrader-reality-tv-big-brother

So “The Irishman” assumes (but crucially doesn’t require) that its audience is conversant (whether directly or indirectly) with the history, the genre, and the framework in which the film operates.

Which, in the internet age, is more accessible than ever to the audience.

Which, in the internet age, is more accessible than ever to the audience.

“What’s in Port Clinton?”

“A plane.”

“A plane? To where?”

“Detroit.”

“We’re going to Detroit now?”

“No, you’re gonna go to Detroit.”

I love how much time “The Irishman” spends on routine and process. It reminds me a bit of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul.”

“A plane.”

“A plane? To where?”

“Detroit.”

“We’re going to Detroit now?”

“No, you’re gonna go to Detroit.”

I love how much time “The Irishman” spends on routine and process. It reminds me a bit of “Breaking Bad” and “Better Call Saul.”

There’s a sense that Frank has detached himself from the work that he does by reducing it to the most banal terms - boiling it down to set of repeatable routines divorced from the actual substance of what he’s doing.

It strips out a lot of the glitz and glamour of the genre.

It strips out a lot of the glitz and glamour of the genre.

“The Irishman” really makes organised crime feel like a 9-to-5 grind, like any other job that would take Frank away from his family.

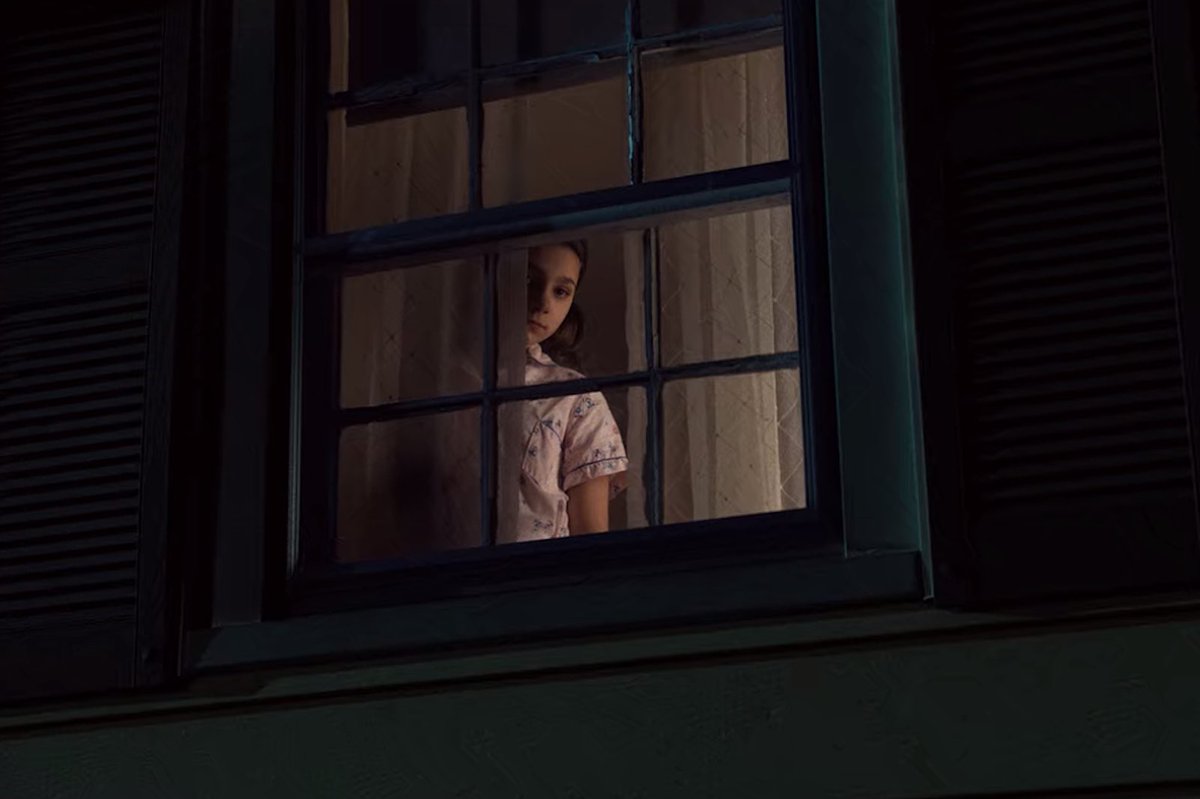

Indeed, the scenes of Frank missing Peggy growing up could come from any other drama about any other absent father.

Indeed, the scenes of Frank missing Peggy growing up could come from any other drama about any other absent father.

(Indeed, this repetition - with the movie’s length - is used well during the lead-up to Frank’s murder of Jimmy, where Scorsese cycles through a number of shots repeatedly to build suspense: the bridge, the crossroads, the house.

All adding to the sense of inevitability.)

All adding to the sense of inevitability.)

“Why?”

I remember the furore over the use of Peggy in “The Irishman”, the complaints that she wasn’t a fully developed character.

While that’s a reasonable criticism, she does get the film’s key moment of moral clarity, which is important.

I remember the furore over the use of Peggy in “The Irishman”, the complaints that she wasn’t a fully developed character.

While that’s a reasonable criticism, she does get the film’s key moment of moral clarity, which is important.

Again, this is the spiritual aspect of “The Irishman.”

Peggy asks Frank why he killed Jimmy, and it’s a question Frank cannot answer - the film implies because he doesn’t actually know why he did it, beyond the fact that he was told to do it.

That might even make it worse.

Peggy asks Frank why he killed Jimmy, and it’s a question Frank cannot answer - the film implies because he doesn’t actually know why he did it, beyond the fact that he was told to do it.

That might even make it worse.

Again, there’s a clear spiritual dimension to this - which naturally plays through Scorsese’s filmography.

After all, it’s the ability to reason that elevates mankind above the animals. Frank’s inability or unwillingness to actually explain himself is to squander that gift.

After all, it’s the ability to reason that elevates mankind above the animals. Frank’s inability or unwillingness to actually explain himself is to squander that gift.

“I picked us over him. F&!k ‘im. F&!k ‘im.”

Frank’s unwillingness to explain or justify himself is contrasted with how readily and how casually Russell makes those excuses.

The interesting question is which of the two is worse. At least Russell seems to understand himself.

Frank’s unwillingness to explain or justify himself is contrasted with how readily and how casually Russell makes those excuses.

The interesting question is which of the two is worse. At least Russell seems to understand himself.

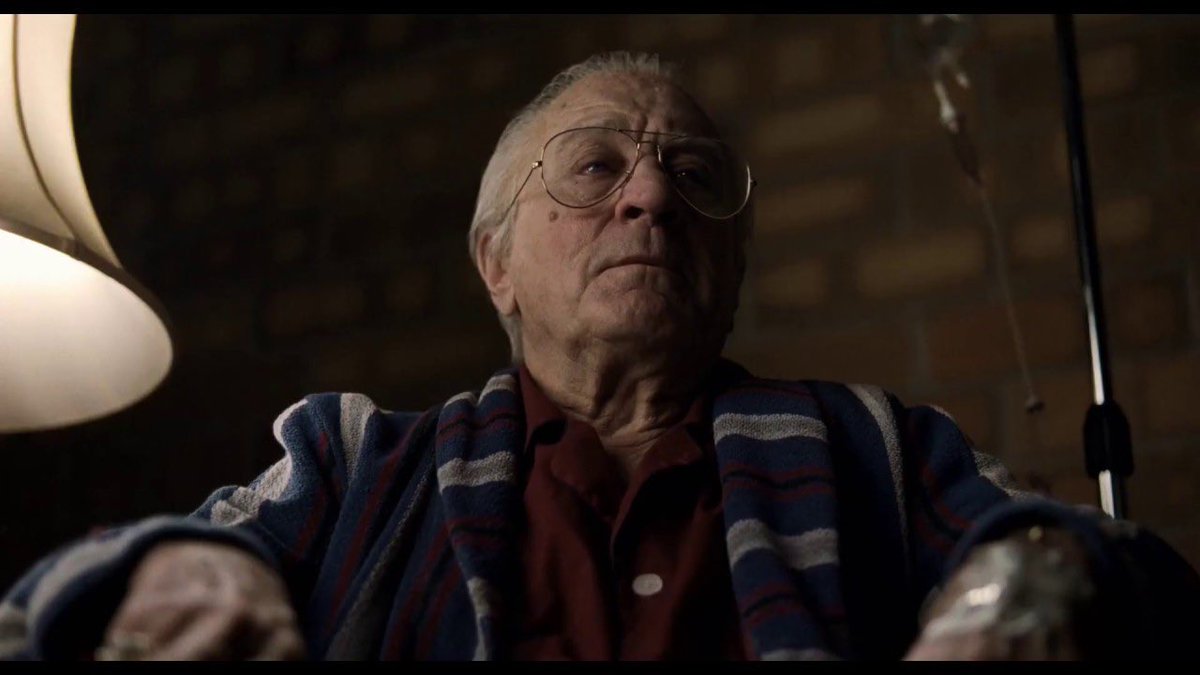

It’s notable that “The Irishman” contrasts the eagerness with which Russell embraces religion and confession in his later life with the difficulties that Frank seems to have even understanding the concept.

In spiritual terms, in an abstract way, maybe Russell can at least atone.

In spiritual terms, in an abstract way, maybe Russell can at least atone.

In a sense, Frank ends “The Irishman” completely alone.

Not only has his entire family abandoned him and his colleagues all passed away, but it seems like his inability to confess because he doesn’t understand his sins may forever isolate him from God.

Not only has his entire family abandoned him and his colleagues all passed away, but it seems like his inability to confess because he doesn’t understand his sins may forever isolate him from God.

My podcast buddy Andrew remarked that the closing scenes of “The Irishman” jokingly argues that “Frank Sheeran will never, ever die.”

While I don’t entirely agree, I do like the idea that Frank has been abandoned even by death itself.

While I don’t entirely agree, I do like the idea that Frank has been abandoned even by death itself.

“The Irishman” is still great.

Incidentally, if you want a three hour and a half discussion of “The Irishman” (there may have been whiskey involved), then check out the episode of @thetwofifty covering the film.

It’s a fun, broad discussion. https://podcasts.apple.com/ie/podcast/the-250/id1170924567?i=1000460363261

Incidentally, if you want a three hour and a half discussion of “The Irishman” (there may have been whiskey involved), then check out the episode of @thetwofifty covering the film.

It’s a fun, broad discussion. https://podcasts.apple.com/ie/podcast/the-250/id1170924567?i=1000460363261

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter