Perhaps the key political cleavage is as follows:

On the one side, those who wish to use the state to remake individuals and civil society so as to make them more free, equal, and prosperous.

On the one side, those who wish to use the state to remake individuals and civil society so as to make them more free, equal, and prosperous.

On the other, those who see equality as equality under the law, freedom as the state acting to protect a narrow well-defined traditional set of rights whilst otherwise leaving individuals and civil society alone, and prosperity as best accomplished via the former two principles.

Hayek might call the former tendency 'rationalist-constructivism' whilst the latter 'classical liberalism'.

Of course, we can't neatly separate people into these two camps: the same two dispositions can exist within the same individual and the same political movement.

Moreover, both tendencies have their important insights and role to play.

(I lean more towards the latter though.)

Moreover, both tendencies have their important insights and role to play.

(I lean more towards the latter though.)

There are a number of ways we can motivate the latter over the former.

One way is to begin with deontological intuitions about individual self-ownernship and non-aggression, and build from there (there are many routes one can take).

One way is to begin with deontological intuitions about individual self-ownernship and non-aggression, and build from there (there are many routes one can take).

Another is the sorts of consideration I outlined in this thread: https://twitter.com/Evollaqi/status/1329762203822592001?s=19

I think these are both good routes.

But Hayek presents a third, very different but also very powerful, means of establishing a preference for 'classical liberalism' over 'rationalist-constructivism'.

(What Jacob Levy might call pluralist vs rationalist forms of liberalism.)

But Hayek presents a third, very different but also very powerful, means of establishing a preference for 'classical liberalism' over 'rationalist-constructivism'.

(What Jacob Levy might call pluralist vs rationalist forms of liberalism.)

For Hayek, the chief problem of "civilisation" is as follows.

There are huge amounts of knowledge, skills, other resources, and self-interest dispersed around the world.

However, any one individual only possesses a miniscule fraction of this total.

There are huge amounts of knowledge, skills, other resources, and self-interest dispersed around the world.

However, any one individual only possesses a miniscule fraction of this total.

How is it that individuals can harness these things for their own benefit, and civilisation can collectively channel and coordinate them for the common good?

And do so peacefully, civilly, and in a way which respects individual liberty?

And do so peacefully, civilly, and in a way which respects individual liberty?

This is especially pressing, as even a small degree of our present level of civilisation requires a huge amount of coordination.

(Read Leonard Read's "I, Pencil" for a poetic description of what goes into our acquiring just one measly pencil.)

(Read Leonard Read's "I, Pencil" for a poetic description of what goes into our acquiring just one measly pencil.)

Hayek argues it's impossible for any individual or collective to "rationally" try to construct this order, even if we gave up on attempting to do so peacefully, civilly, and respectful of individual liberty.

The amount of knowledge to be a) acquired and b) processed is just too vast, and our capacities just too limited.

Moreover, he argues that any attempt to engage in such a "rational" project to construct an order will not only be doomed to failure but also inevitably totalitarian: it would require attempting to impose control over everyone and everything, and against differing wills.

Similar can be said for any other aims we collectively assign ourselves.

The world is too far the ken of any individual mind to know the consequences of their actions, so any deliberate endeavour to achieve something on such a scale will be sub-optimal at best.

The world is too far the ken of any individual mind to know the consequences of their actions, so any deliberate endeavour to achieve something on such a scale will be sub-optimal at best.

So what is the solution?

Hayek points us to evolutionary biology: there, order emerges with no single mind planning it or controlling it.

More generally: just as scientific development in the natural sciences required us to put aside our instinctual agency detection

Hayek points us to evolutionary biology: there, order emerges with no single mind planning it or controlling it.

More generally: just as scientific development in the natural sciences required us to put aside our instinctual agency detection

and see order without design, development in the social sciences requires the same.

Hayek says we see emergent orders amongst human beings.

Every one of us is part of multiple extended orders, going far beyond what we can understand as individuals and collectives.

Hayek says we see emergent orders amongst human beings.

Every one of us is part of multiple extended orders, going far beyond what we can understand as individuals and collectives.

The examples he gives are:

1. Traditions such as morals and customs.

Indeed, he thinks humanity's triumph in biological evolution stems from having developed the capacity to have traditions). A tradition knows more than any one of us does, and moreover

1. Traditions such as morals and customs.

Indeed, he thinks humanity's triumph in biological evolution stems from having developed the capacity to have traditions). A tradition knows more than any one of us does, and moreover

it is impossible for any one of us to justify all of our beliefs and practices – most of what we think and do can only be justified via tradition. Without tradition we are left with very little.

2. Law, which he distinguishes from legislation. The former is an order which emerges (eg the common law from countless judicial precedents, each applied to the particular issue before it), the latter is an ordering pronounced from on high.

3. Language (who designs one?)

3. Language (who designs one?)

4. Hayek's favourite example: markets. Competition and free exchange generate spontaneous orders which channel individual self-interest to higher quality, lower prices, greater efficiency, and more innovation for society as a whole.

Through the price system, the vast dispersed knowledge of humanity are harnessed and the variegated plans of different individuals and groups are coordinated – peacefully, civilly, respectful of individual liberty – creating the greatest engine of prosperity in human history.

Hayek argues these extended orders arise under conditions of competition.

Any trait which arises that is able to more efficiently solve the civilisational coordination problem – whether the trait is brought about for a different purpose entirely,

Any trait which arises that is able to more efficiently solve the civilisational coordination problem – whether the trait is brought about for a different purpose entirely,

or is totally random, or is deliberately intended for this goal – is likely to propagate.

Selection pressures in the form of population growth, geographical size, material and technological superiority, migration, etc in favour of the society with the trait.

Selection pressures in the form of population growth, geographical size, material and technological superiority, migration, etc in favour of the society with the trait.

We also see the trait spreading through imitation, conquest, market dominance, and so on.

Competition also acts as a discovery procedure. Through trial-and-error, we learn more about how things work (eg 'if A then B'), uncover new possibilities, and

Competition also acts as a discovery procedure. Through trial-and-error, we learn more about how things work (eg 'if A then B'), uncover new possibilities, and

identify more of people's wants and what satisfied them.

How does Hayek's picture bring about 'classical liberal' rather than 'rationalist-constructivist' conclusions?

How does Hayek's picture bring about 'classical liberal' rather than 'rationalist-constructivist' conclusions?

As a private individual, you ought to obey evolved general rules (even if you cannot rationally justify them directly), and pursue your own individual plans underneath them.

This behaviour in aggregate will strongly tend towards doing the best we can for

This behaviour in aggregate will strongly tend towards doing the best we can for

ourselves as individuals and for the cause of civilisation, and almost certainly more than "rationally" and directly aiming for those goals independently of the evolved rules.

As an individual in a position of public authority, or as a collective, the best thing for individuals and civilisation is not to try to rationally construct a good society – but to promote competition and otherwise leave the extended orders alone to their own devices.

Following these principles can be uncomfortable.

Firstly, our atavistic instincts were not evolved for anonymous mass society – and all its tremendous possibilities for civilisation – but for much smaller and more primitive groups.

Firstly, our atavistic instincts were not evolved for anonymous mass society – and all its tremendous possibilities for civilisation – but for much smaller and more primitive groups.

Tradition (including morality) lie in between our instincts and our reason – logically, causally, and temporally – and serve to get us to suppress our instincts for the sake of our individual benefit and civilisation, even where we're unable to rationally anticipate this benefit.

Tradition also serves as the ground on the possibility of our (limited but real capacity for) rationality, which isn't for Hayek some free floating Platonic thing, but itself an evolved and evolving product, and a tradition of its own.

Secondly, "intellectuals" are by their very definition people who seek to rationally question whatever they can, and think of ways to order society.

These are tendencies they need to resist, and rationally recognise the limits of their own reason.

These are tendencies they need to resist, and rationally recognise the limits of their own reason.

Thirdly, if our moral beliefs and practices are an evolved order or part of an evolved order, then it means we will inevitably – and ought to – move beyond our current morality to new ones.

This is something which we will definitionally find goes against our sense of morality.

This is something which we will definitionally find goes against our sense of morality.

Another upshot of Hayek's approach is his argument that "social justice" (by which he means

distributive justice) is a category error.

If there was a central planner who owned and ordered everything, then there would be a question of how they ought to distribute resources.

distributive justice) is a category error.

If there was a central planner who owned and ordered everything, then there would be a question of how they ought to distribute resources.

But there isn't.

Per evolved general rules, individuals mostly own themselves, and have rights to what Hayek calls "severable property".

Moreover, distribution should and can only be done primarily on the basis of emergent orders, comprised of the free decisions of millions if

Per evolved general rules, individuals mostly own themselves, and have rights to what Hayek calls "severable property".

Moreover, distribution should and can only be done primarily on the basis of emergent orders, comprised of the free decisions of millions if

not billions of people.

This is not only what in fact largely happens and what's demanded by individual liberty, but no central planner can have access to the knowledge (or ability to process it) required to order resources in any other way such that civilisation can keep going.

This is not only what in fact largely happens and what's demanded by individual liberty, but no central planner can have access to the knowledge (or ability to process it) required to order resources in any other way such that civilisation can keep going.

I find Hayek's argument overall a compelling one, alongside the two other arguments I mentioned for 'classical liberalism'.

However, it is not without its issues.

However, it is not without its issues.

Firstly, whilst his account of reality seems true in the abstract, it is hard to see (i) how to add greater specificity to it so as to make it a workable approach to the social sciences, and (ii) how to draw specific policy recommendations from it.

Secondly, as outlined by Jacob Levy Hayek's support for emergent orders and opposition to rational-constructivism are often in tension: https://twitter.com/Evollaqi/status/1342994489242218496?s=19

For instance, the economic orders he lauds were often the product of intentional state design

For instance, the economic orders he lauds were often the product of intentional state design

and understood as such by the very thinkers – such as Smith – who Hayek cites in favour of his understanding of emergent economic order.

Likewise, whilst (very disputably) Britain's classical liberalism was an emergent order, there may be no guarantee that this is what we

Likewise, whilst (very disputably) Britain's classical liberalism was an emergent order, there may be no guarantee that this is what we

should usually expect from competition and otherwise leaving emergent orders to their own designs.

Note that Hayek himself opposes the notion of "laissez-faire", seeing it as rationalist-constructivist ideology, and instead sees the proper roles and limitations of the state

Note that Hayek himself opposes the notion of "laissez-faire", seeing it as rationalist-constructivist ideology, and instead sees the proper roles and limitations of the state

as something properly left to emergent order.

Thirdly, it seems Hayek's thought requires being supplemented by another moral or political theory.

Why is it that we should care about "civilisation", ie solving these coordination problems?

Thirdly, it seems Hayek's thought requires being supplemented by another moral or political theory.

Why is it that we should care about "civilisation", ie solving these coordination problems?

Hayek implicitly seems to take it for granted that the fruits of this – prosperity, peace, civility, individual liberty – are valuable.

We would need an account of why they are so, and a consequentialist system which aims towards one is the correct one.

We would need an account of why they are so, and a consequentialist system which aims towards one is the correct one.

Perhaps this supplemental moral or political theory would also allow us to solve the other two problems: giving us the ability to flesh out Hayek's thought and apply it to policy, and reconcile emergent orders and an antipathy to rational-constructivism in the state.

The other two arguments for 'classical liberalism' I supplied may just be, or be part of, such a supplemental framework.

Hayek spoke about the need for us to not be reactive conservatives, but have a positive liberal vision we can aim towards.

Hayek spoke about the need for us to not be reactive conservatives, but have a positive liberal vision we can aim towards.

A system based on deontological intuitions of individual self-ownernship and non-aggression, scepticism of the state and singular conceptions of the true and good on intrinsic and efficacy grounds, and the crucial importance of emergent orders could be just such a vision.

Unless we see the first two of these three limbs as contingent evolved morals and rational beliefs that the latter mandates we eventually move beyond.

It's hard to see how any normative system could be appended to a theory which sees all such systems as imperfect and temporary.

It's hard to see how any normative system could be appended to a theory which sees all such systems as imperfect and temporary.

These were my reflections on this week's book club! https://twitter.com/likeplastic_/status/1341296093280276480?s=19

It would also be odd if what turns out to be best on deontological grounda also turns out to be best on consequentialist grounds (eg those who justify libertarianism on both grounds simultaneously) – why would reality turn out to be that convenient?

I don't think we should see the selection pressures as only having a general tendency towards improvement per se, sometimes it can be towards adaptation to changing circumstances.

Eg a new technology develops, old norms etc are no longer optimal, they get replaced over time.

Eg a new technology develops, old norms etc are no longer optimal, they get replaced over time.

This is rather like the Marxist idea of historical materialism (especially GA Cohen's rational-choice technological-determinist version).

Hayek himself points out a key difference though: biological evolution, and his view of evolution, are non-deterministic and produces

Hayek himself points out a key difference though: biological evolution, and his view of evolution, are non-deterministic and produces

a multitude of different actual and possible developments

Whereas Marxism misunderstands evolution, seeing there to be 'laws of evolution' as there are for, say, Newtonian mechanics – and accordingly supposes that history moves in a deterministic, predictable, and linear manner

Whereas Marxism misunderstands evolution, seeing there to be 'laws of evolution' as there are for, say, Newtonian mechanics – and accordingly supposes that history moves in a deterministic, predictable, and linear manner

(Hayek accuses what he sees to be the grossly mislabeled "social Darwinists" as making the same error)

Still, to the extent there is a similarity between Hayek and Marx on historical progress I don't think this is a coincidence. Both are influenced by the Whig theory of history.

Still, to the extent there is a similarity between Hayek and Marx on historical progress I don't think this is a coincidence. Both are influenced by the Whig theory of history.

Marx as he was an Enlightenment thinker through and through, and thus shared the era's prevalent views on historical progress.

Hayek as he was in many ways the intellectual successor to Burke, who was a Whig MP and who I read as providing a sort of defence of Whig history.

Hayek as he was in many ways the intellectual successor to Burke, who was a Whig MP and who I read as providing a sort of defence of Whig history.

Namely, that history progresses, but it does so through the organic development of tradition, and not through the ratiocination of human beings – which in the name of advancement can actually result in changes greatly contrary to genuine advancement.

When discussing competition as providing a discovery procedure via trial-and-error above, I should have added that this form of empiricism is likely to give us better insight than a priori armchair reflection or empirical labwork

This thread is becoming rambly, but another point to add is re the discussion of atavism above.

Another reason why we might not instinctively like the optimal traditions for anonymous mass society is that they jar with the optimal traditions for some subunits within it.

Another reason why we might not instinctively like the optimal traditions for anonymous mass society is that they jar with the optimal traditions for some subunits within it.

For instance, the morality appropriate for inside the family or is completely inappropriate for civilisation as a whole and vice versa, so it's not surprising our conditioning inside the family leaves us averse to what we ought to do outside of it.

(In the other direction, this might be part of what inspires calls for things like family abolition, incorrectly applying the morality we're used to in the market or another large group to our kin or close friendships.)

Above, when I spoke of the wonders of markets as coordinating mechanism, I focused on competition and ignored an even more fundamental feature of markets: that of exchange itself.

Free exchange is typically 'Pareto improving': that is, some people improve their position without

Free exchange is typically 'Pareto improving': that is, some people improve their position without

others having their position worsened.

If I agree to trade X to you in exchange for Y, I must prefer (or at least be indifferent to) having Y to having X.

If you agree to give me Y in exchange for X, you must prefer (or at least be indifferent to) having X to having Y.

If I agree to trade X to you in exchange for Y, I must prefer (or at least be indifferent to) having Y to having X.

If you agree to give me Y in exchange for X, you must prefer (or at least be indifferent to) having X to having Y.

Accordingly, in markets typically the way to getting more of what you want (eg money) is by providing other people what they want (eg labour or goods or services).

So self-interest is channelled towards benefiting others.

So self-interest is channelled towards benefiting others.

This effect is then compounded by market competition. When you need to compete with others in order to buy and sell what you want, this inventivises you to improve efficiency and quality and to innovate.

Then, through various interrelated mechanisms (market equilibrium, price signals, the division of labour, etc), markets allow people's preferences, self-interest, skills, and resources to be coordinated on a mass scale.

(Again, see "I, Pencil" for an example of this.)

(Again, see "I, Pencil" for an example of this.)

A few things to note:

1. Exchange need not be monetary. There are all manners of things – tangible and intangible – that human beings can exchange with each other.

2. "Self-interest" need not be selfish. By this, I don't *only* mean that markets channel self-interest to the

1. Exchange need not be monetary. There are all manners of things – tangible and intangible – that human beings can exchange with each other.

2. "Self-interest" need not be selfish. By this, I don't *only* mean that markets channel self-interest to the

benefit of others. I also mean that "self-interest" itself – ie what is being channeled towards benefiting the self-interest of others – need not be selfish.

When economic models assume agents are "self-interested", this means that it is assumed agents are acting in pursuit of

When economic models assume agents are "self-interested", this means that it is assumed agents are acting in pursuit of

their own preferences rather than other. But one's preferences can be either altruistic or selfish! Abdul Sattar Eidhi's preferences were probably mostly to act on what he believed to be the welfare of others, whilst this isn't the case for Gordon Gecko.

Even if a gun is held to your head by someone telling you to do X, and you do X as a result, it is still your preferences being acted upon (ie you prefer to keep your life and do X, than die and not do X).

And in any case, in *free* exchange this type of coercion is excluded.

3. Free exchange may not be Pareto improving if we understand "benefit" and "harm" in objective terms rather than in terms of the subjective preferences of the agents involved.

3. Free exchange may not be Pareto improving if we understand "benefit" and "harm" in objective terms rather than in terms of the subjective preferences of the agents involved.

But taking a subjective account of benefit is the least authoritarian and most pluralist route in politics. We don't presume to know what is better for people than what they actually want.

(And we sensibly understand "what they actually want" in terms of their revealed preferences, and not their stated preferences.)

4. There are limits to the virtues of free exchange.

Eg, free exchange may not be Pareto improving where there are negative externalities involved.

4. There are limits to the virtues of free exchange.

Eg, free exchange may not be Pareto improving where there are negative externalities involved.

Likewise, an emergent order of free exchanges may not be 'Pareto optimum' (ie a situation where no one can be made better off without making someone worse off) where there are positive externalities involved.

More generally, externalities are one kind of market failure meaning

More generally, externalities are one kind of market failure meaning

that the emergent order may not Pareto optimum. There are other kinds of market failure too.

There are also macro-level effects ie where free exchange at the micro level gives rise to a sub-optimal emergent order – we often see this in recessions, for instance.

There are also macro-level effects ie where free exchange at the micro level gives rise to a sub-optimal emergent order – we often see this in recessions, for instance.

5. Seemingly socially negative things which arise for markets can in fact be positive (when considering everyone who is affected and in the long-run, rather than those who have just been negatively affected in the short run).

For instance, if technological innovation or increasing trade leads to lay-offs, this means that a) a good or service X has now become more affordable, in effect increasing our purchasing power; and b) we now have a lot of labour freed up which can now be put to other uses

whilst retaining the amount of X produced, thus increasing our total production.

We no longer lament candle-workers being made redundant by the light bulb.

Innovation and trade usually also mean we get new goods or services that we didn't before, making it even more beneficial.

We no longer lament candle-workers being made redundant by the light bulb.

Innovation and trade usually also mean we get new goods or services that we didn't before, making it even more beneficial.

As aforementioned, Hayek himself was explicitly against laissez-faire.

Markets are co-evolved alongside the state and other formal and informal instutions, and they form an extended order with each other, requiring each other for existence.

Markets are co-evolved alongside the state and other formal and informal instutions, and they form an extended order with each other, requiring each other for existence.

And even if markets could be left alone by these other institutions, this would be far from optimal.

But our starting point has to be that markets are for the most part brilliant (and this is not just at the level of history – they are part of why the last 200 years of history

But our starting point has to be that markets are for the most part brilliant (and this is not just at the level of history – they are part of why the last 200 years of history

have made us more prosperous than anyone at any point before then could have ever conceived), and from there we can speak about their limitations and tinker around with them.

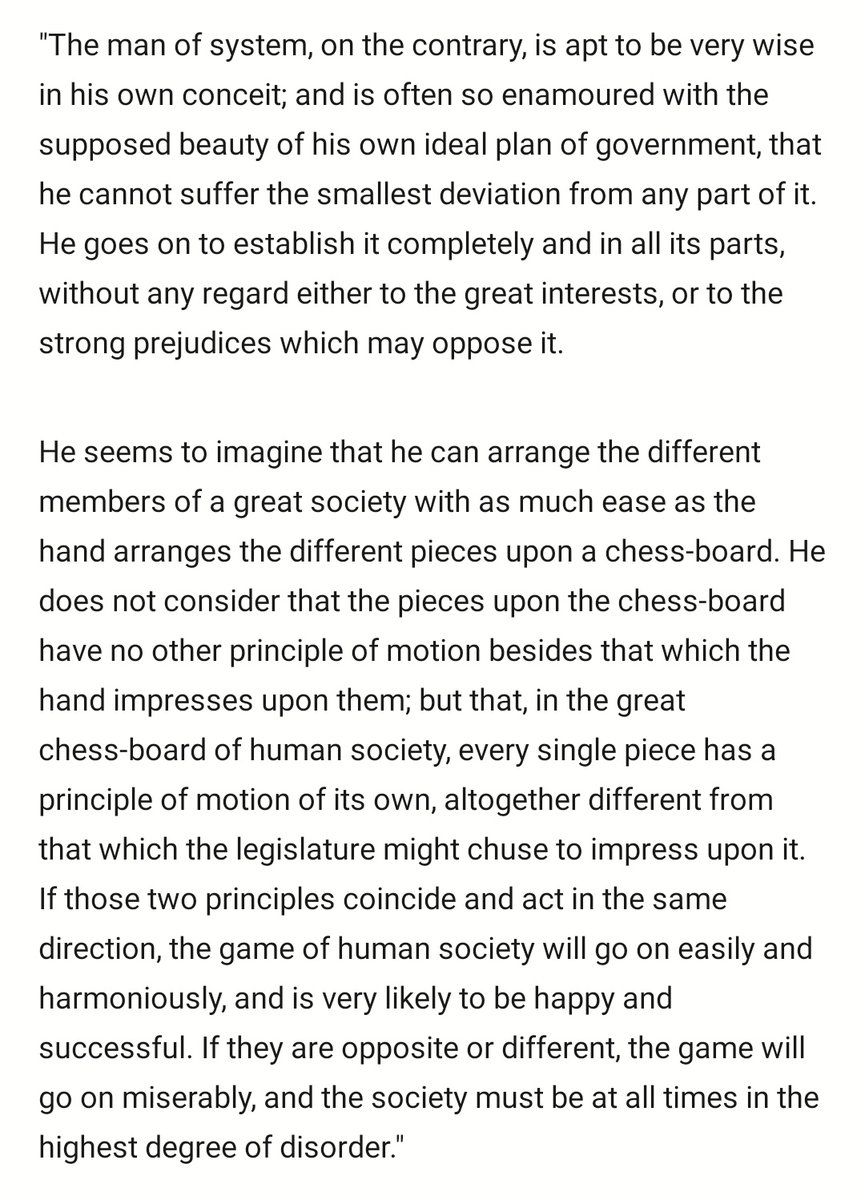

The passage of Adam Smith whence Hayek derived the title of his book "The Fatal Conceit".

The fundamental fallacy of economic planning is to assume society is like a giant chessboard and the individuals are its pieces, to be moved around at will.

The fundamental fallacy of economic planning is to assume society is like a giant chessboard and the individuals are its pieces, to be moved around at will.

Rather, each individual has a principle of motion of its own, and thus cannot easily be controlled, let alone games involving prediction and planning be played with them.

Moreover, any attempt to make human beings into chess pieces would inevitably be tyrannical

Moreover, any attempt to make human beings into chess pieces would inevitably be tyrannical

suppressing their individual motion and enforcing movement onto them.

Rules impressed upon individuals thus must be consonant with their motion.

Hayek – though not Smith (see Levy's lecture above) – believed evolved rules rather than "rational" state legislation provided these.

Rules impressed upon individuals thus must be consonant with their motion.

Hayek – though not Smith (see Levy's lecture above) – believed evolved rules rather than "rational" state legislation provided these.

The opening to Hayek's "The Fatal Conceit" https://twitter.com/likeplastic_/status/1342192142144430084?s=19

Note that the selection and discovery processes which led to the predominance of markets in the developed world, also apply within markets - one core way markets are effective.

Market competition selects for, and discovers, the best entities and practices.

Market competition selects for, and discovers, the best entities and practices.

Milton Friedman explaining the beauty of market coordination by summarising "I, Pencil"

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter