When “The Blue Lotus” appeared in 1936, Hergé was 29 years old and approaching the peak of his powers as an artist.

“In terms of quality there is a before and after ‘The Blue Lotus,’” says Eric Leroy. https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-tintin-taught-europeans-about-china-11608919200

“In terms of quality there is a before and after ‘The Blue Lotus,’” says Eric Leroy. https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-tintin-taught-europeans-about-china-11608919200

Part of the story is based on the Mukden Incident of 1931, in which Japanese soldiers blew up a section of the South Manchuria railway and blamed the act on the Chinese, creating a pretext for Japan’s invasion of Manchuria.

“When ‘The Blue Lotus’ was originally serialized in 1934, western Europeans were terribly pro-Japanese.”

The story prompted an official protest to Belgium’s foreign ministry by the Japanese government.

The story prompted an official protest to Belgium’s foreign ministry by the Japanese government.

Far from laudable though is the fact while Belgium was under German occupation during World War Two, Tintin was published in a pro-Nazi paper, Le Soir.

The Shooting Star, first published in 1941, had a stereotypical Jewish villain, a wealthy industrialist called Blumenstein.

The Shooting Star, first published in 1941, had a stereotypical Jewish villain, a wealthy industrialist called Blumenstein.

On the other hand, Herge’s pre-war King Ottakar’s Sceptre has a poke at fascism, with one villain named Mussler, an apparent combination of Mussolini and Hitler.

Democracy is not necessarily promoted in the books.

The benevolent Ottakar was an absolutist monarch. Tintin was also pals with two dictators who ruled with an arbitrary iron hand, General Alcazar and Emir Ben Kalish Ezab.

The benevolent Ottakar was an absolutist monarch. Tintin was also pals with two dictators who ruled with an arbitrary iron hand, General Alcazar and Emir Ben Kalish Ezab.

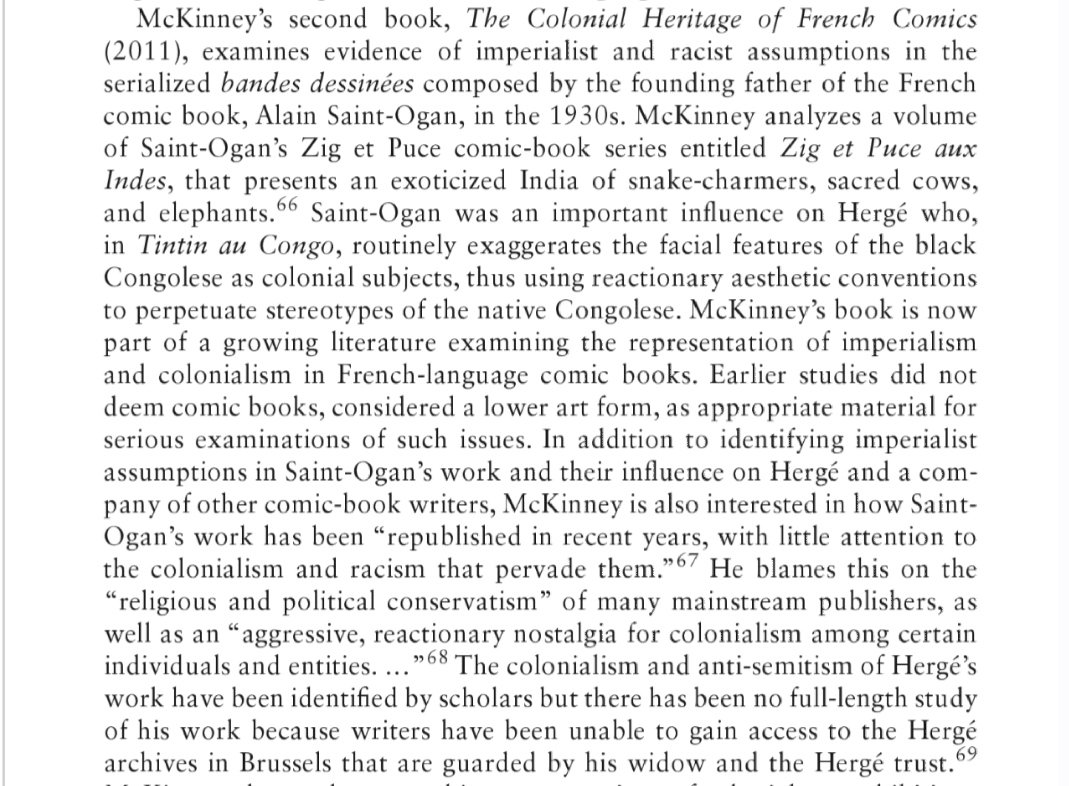

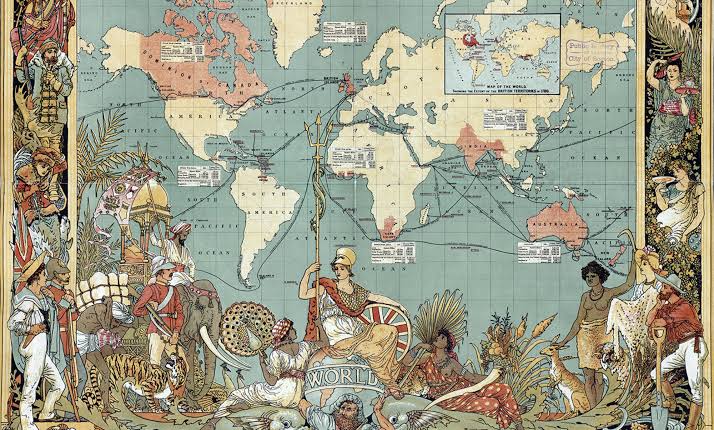

While Tintin in the Congo is a colonial rant, in which he chased gangsters, dispensing his patronizing white man’s wisdom to stupid and lazy monkey-like natives, the book largely reflected contemporary Belgian attitudes to its colony.

His cartoons reflected the values of the 20th century - and have since drawn criticism. However, Hergé's style also evolved over the years.

To understand the present, we must first understand the past, for the past is still with us.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/apr/07/1

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2002/apr/07/1

The European Union has become a highly developed system for mutual interference in each other's domestic affairs, right down to beer and sausages.

"Postmodern states" like the EU and Japan now accept a high level of international integration and are more concerned with the well-being of citizens than the pursuit of national grandeur.

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/the-breaking-of-nations-order-and-chaos-in-the-21st-century-by-robert-cooper-79439.html

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/reviews/the-breaking-of-nations-order-and-chaos-in-the-21st-century-by-robert-cooper-79439.html

Europe, because it has not yet got a convincing security policy of its own, remains uncomfortably dependent on US military support, even in European crises such as those in the former Yugoslavia.

The elusive, protracted, and unceremonious slew of events that came to be known as “Brexit” continues to frame assessments of difference and sameness, freedom and dependence, regional alliances and cultural entitlements, and discourses of national health and viral threat.

Brexit has triggered large-scale speculations about social insecurities and national trauma.

It has bolstered populism, prejudice, yet also instilled a sense of hope and renewal, not least among its apologists, lobbyists, and also sizeable sections of the British population.

It has bolstered populism, prejudice, yet also instilled a sense of hope and renewal, not least among its apologists, lobbyists, and also sizeable sections of the British population.

To be sure, Brexit is not a bona fide postcolonial event.

But, it represents a moment when anxieties about harnessing and unleashing colonially engineered power structures and cultural hierarchies crystallized.

But, it represents a moment when anxieties about harnessing and unleashing colonially engineered power structures and cultural hierarchies crystallized.

If Britain’s departure from its colonies marked the end of colonialism as we knew it, then, for some, Britain’s departure from the EU marked the end of yet another kind of colonialism.

In his resignation letter as Foreign Secretary on July 9, 2018, Boris Johnson warned that Theresa May’s Brexit plan would reduce Britain to “the status of a colony”.

What was formulaic about Johnson’s projection was the sheer imaginary bankruptcy: a colonizer assuming the role of the colonized.

This is by no means unique to Johnson or the Leave campaign.

This is by no means unique to Johnson or the Leave campaign.

Populist appropriations of the COVID-19 pandemic, too, are rolled into this logic, as in public appeals that Britain should muster warlike endurance to extricate itself from both the clutches of the coronavirus and the grip of the EU.

Theresa May’s “truly global Britain” may not be all that global in outlook but poised on a selective, if not a skewed, representation of Britain’s role in colonial history that postcolonial studies is best equipped to articulate.

Populist campaigns built around the commingled tropes of Brexit, empire, and World War II have proven highly effective across various sections of British society, and have exerted a particular force amongst those who witnessed the gradual crumbling of empire after the war.

World War II was the last large-scale political and military event affording untainted heroism before the empire collapsed entirely – and with it, if more gradually and more uncertainly, its moral legitimacy.

As such, World War II was the last incarnation of a kind of British imperial fortitude that continues to facilitate a safe and legitimate sense of national attachment, particularly in times of upheaval.

For the populist camps, Britain’s EU membership has helped to sustain a victim-like, sacrificial, and defensive position, giving ample opportunity for constructing the country as having to fend off inferiorizing “onslaughts” of EU bureaucrats, and abject invasions of immigrants.

In its continuing predilection for self-aggrandizing visions of empire, as well as a lack of critical self-positioning in relation to its imperial history, Britain remains vulnerable to “the threat posed by injured white nationalism”.

It reveals not only the perverse flexibility of populist discourses – to arrogate, appropriate, and even claim the discursive position of the colonized – but also a continuing inability to conceive of transnational cooperation outside the framework of domination and victimhood.

Given its grievances over the perils of domination and perceived victimhood, parts of the Brexit debate are narcissistically invested in hierarchical, controlling relationships (“take back control”), rather than more balanced, inclusive, and socially just models of cooperation.

A shame that does not transform into guilt can effectively lead to a “narcissistic rage that does not really care for the ones who have been wronged but only grieves the loss of social recognition”.

For Britain, this rupture in the affective pact between shame and guilt represented an abject loss of its recognition worldwide.

The appropriation of the colonized position by none other than the Prime Minister is neither innocent nor premediated, but an unfortunate consequence of his inability to come to terms with empire’s injurious past that ultimately shaped the Leave campaign’s exceptionalist logic.

Brexit has revived those remains of empire’s narcissistic nationalism that now militate against the very idea of Europe.

Both Dunkirk and Darkest Hour rehearse the the “cruel nostalgia” with which World War II as a subchapter of Britain’s imperial history is remembered.

The Leave campaign also brought together an unusually broad coalition of forces, stretching from George Galloway on the Left to Nigel Farage on the Right.

Nostalgia and amnesia are both pathological forms of memory, based on curated versions of the past, but they work to different ends.

Tony Benn, who led the Labour Leave campaign in 1975, was mocked in The Sun as “the last British imperialist rampant, still inhabiting a world in which the poor countries sell us their food and raw materials on the cheap and gratefully purchase our manufactured goods.”

Australia's Gough Whitlam, who endorsed British membership, deployed the same trope at a news conference in 1975, urging the United Kingdom not to “lapse into the position of Spain – looking to a mighty empire in the past and a peripheral influence for the future”.

For some supporters of membership, it was precisely this appetite for leadership that underpinned the case for entry.

Patrick Ground, a future Conservative MP, told reporters in 1975 that “it was natural for our country – with its record as a colonial power … to want to exercise some influence on the future development of Asian and African countries”.

The Liverpool Daily Post predicted that entry would facilitate “a new upsurge of British influence and set us on the road to a new era of greatness”.

Thatcher bowed to no one in her enthusiasm for the empire, which she considered “a fantastic thing”.

Yet for most of her career, she invoked memories of empire not as an alternative to ‘Europe’ but as part of a common European heritage.

Yet for most of her career, she invoked memories of empire not as an alternative to ‘Europe’ but as part of a common European heritage.

Likewise, when David Cameron launched the Remain campaign in 2016 – requiring him, for the first time, to articulate a position in support of European membership – it was to this theme that he instinctively turned.

Enoch Powell, reflecting in 1991 on his youthful enthusiasm for empire, lamented the ‘gigantism’ it had left behind, spawning a “delusion that big is great” and a “bullfrog mentality, which has haunted Britain ever since”.

In the 1970s, both the Bennite Left and nationalist parties such as Sinn Féin, Plaid Cymru and the SNP adopted the rhetoric of colonial liberation, presenting the EEC as a collection of white, post-colonial states, working to maximize their power and influence.

The historian and founder of UKIP, Alan Sked, described Euroskepticism as “a demand for decolonization from Brussels”, not as an example of imperial nostalgia.

The turn to Europe as a vehicle for Britain’s leadership ambitions reflected, in part, a disillusionment with the Commonwealth as an instrument of British power.

For much of the post-war era, the Tory Right was scarcely less hostile to the Commonwealth than to the European Community, while Euroskeptics of the Left prized the Commonwealth precisely for its deviation from the imperial idea.

During the Cold War, it could be viewed either as a bulwark against Soviet influence or as a ‘third force’ between East and West.

A 1956 Conservative report hailed it as a new basis for British power.

A 1956 Conservative report hailed it as a new basis for British power.

Under the leadership of Sonny Ramphal, its Secretary-General from 1975 to 1990, the Commonwealth became a point of pride that it had lost its ‘Britishness’, and would never again “become the creature of Britain or any other single member country”.

A Foreign Office Report in 1972, written as Britain prepared to join the EEC, complained that Britons had “paid a high, and perhaps an excessive price” for the Commonwealth connection.

Writing in 1960, Labour’s former Commonwealth Secretary, Patrick Gordon Walker, hailed the organization as the “negation of imperialism”, based not upon the “predominance of British power” but on equality and partnership.

Harold Wilson was at pains to distinguish the “imperialist yearnings” of the Conservative Party from Labour’s enthusiasm for the Commonwealth, an organization fit for “the post-colonialist age in which we live”.

Enoch Powell was as hostile to the Commonwealth as he was to the Common Market, deriding it as a ‘myth’, and a ‘farce’.

Over the 1970s and 80s, its association with left-wing politics, multiracial immigration and anti-colonialism made it scarcely less of a bogey than Brussels.

Over the 1970s and 80s, its association with left-wing politics, multiracial immigration and anti-colonialism made it scarcely less of a bogey than Brussels.

The collapse of apartheid removed the longest-running sore in Commonwealth relations, while enabling some who had once supported the apartheid regime to trumpet the role of British and Commonwealth diplomacy in bringing it to a close.

In consequence, it became possible once again to imagine the Commonwealth as an alternative to European integration – one that imposed no costs or obligations, but was allegedly more in tune with ‘Anglo-Saxon’ values.

UKIP, in particular, increasingly presented the Commonwealth states as ‘family’, whose wartime sacrifice made them “more worthy of our friendship”.

A ‘reinvigorated Commonwealth’, it suggested in 2014, was “a real alternative to … the European Union”.

A ‘reinvigorated Commonwealth’, it suggested in 2014, was “a real alternative to … the European Union”.

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, in 2013, Boris Johnson denounced the ‘infamous’ decision to join the European Community in 1973 for “betraying our relationships with Commonwealth countries such as Australia and New Zealand.”

During the 2016 referendum, the most powerful appeals to the Commonwealth were directed at Britain’s 4 million Black and Asian voters.

The idea that Britain should “build connections with the Commonwealth, rather than Europe” was widely ventilated by Leave campaigners.

The idea that Britain should “build connections with the Commonwealth, rather than Europe” was widely ventilated by Leave campaigners.

Writing on 2016 has focused overwhelmingly on the motives of Leave voters; yet research suggests that Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) voters backed Remain by 68% to 31%, with even higher figures for those identifying as Black, Chinese, Muslim or Hindu.

Until the 1990s, Black and Asian voters had been viewed chiefly as a Leave constituency.

During the first referendum, in 1975, the Indian Workers’ Association distributed 10,000 leaflets in the Midlands “urging a massive ‘No’ vote”.

During the first referendum, in 1975, the Indian Workers’ Association distributed 10,000 leaflets in the Midlands “urging a massive ‘No’ vote”.

Groups such as ‘Asians for Europe’ and ‘Commonwealth for Europe’ distributed material in Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi and Urdu, urging the trading benefits for the Commonwealth if Britain could act as a bridgehead into European markets.

Voting Leave, Priti Patel insisted, would enable “a fair immigration policy which would bring in the best from countries like India, Bangladesh, Australia and New Zealand”.

She also backed a ‘Save our British Curry’ campaign, endorsed by the Bangladesh Caterers’ Association.

She also backed a ‘Save our British Curry’ campaign, endorsed by the Bangladesh Caterers’ Association.

Even Nigel Farage, an unlikely apostle of multi-racial immigration, claimed that Brexit would facilitate a non-discriminatory system, under which “more black people would qualify to come in”.

Shortly after the referendum, Priti Patel reminded a meeting of Commonwealth trade ministers that “In some of the darkest days in world history, it has been our friends and allies in the Commonwealth who have remained steadfast on the side of freedom”.

As in 1975, Commonwealth leaders had mostly backed British membership, or had come as close to doing so as decorum permitted.

In the Asian press, much was made of remarks by India's Modi, on Britain’s role as India’s “entrypoint … to the European Union”.

In the Asian press, much was made of remarks by India's Modi, on Britain’s role as India’s “entrypoint … to the European Union”.

The Labour MP Khalid Mahmood, who had joined the Leave campaign from a desire “to end EU visa discrimination against our Commonwealth Citizens”, defected to Remain, describing Johnson’s remarks as “totally racist”.

Like the Anti-Marketeers of the 1970s, who marched under the banner ‘Out of Europe and Into the World’, Brexiteers presented withdrawal as a chance to steer the ship of state out of the backwaters of Europe and into the open seas of the wider world.

For its advocates, ‘Global Britain’ was not a ‘narrative of empire’ but a narrative of greatness, which relegated the empire to a purely expressive role.

It was sustained, not by knowledge of past imperial successes, but by amnesia and apathy.

It was sustained, not by knowledge of past imperial successes, but by amnesia and apathy.

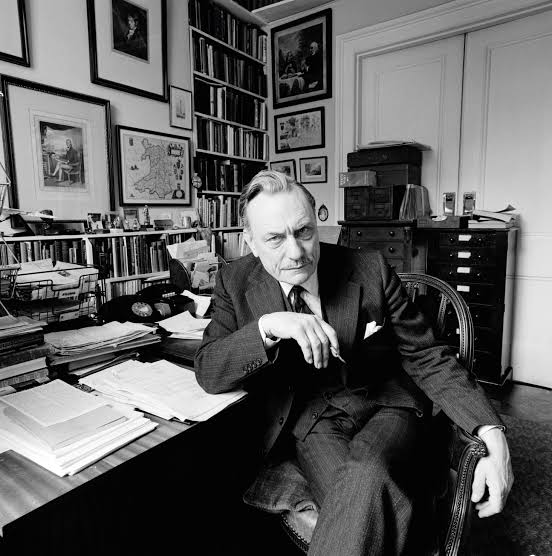

Enoch Powell (1912-1998) was an early proponent of the idea that ‘all history is myth’ – not in the sense that it was untrue, but in that the stories told about the past carry political meanings, which exert power in the present.

For Powell, post-war Britain was in the grip of an especially pernicious myth, which he called ‘the myth of empire’: the “illusory notion that Britain was once great because she had an Empire and is now small and weak because she has one no longer”.

As early as 1957, Powell had concluded that “the Tory Party must be cured of the British Empire”.

In a series of books, articles and speeches, he set out to establish “a new patriotism” that could replace the “imperial patriotism of the past”.

In a series of books, articles and speeches, he set out to establish “a new patriotism” that could replace the “imperial patriotism of the past”.

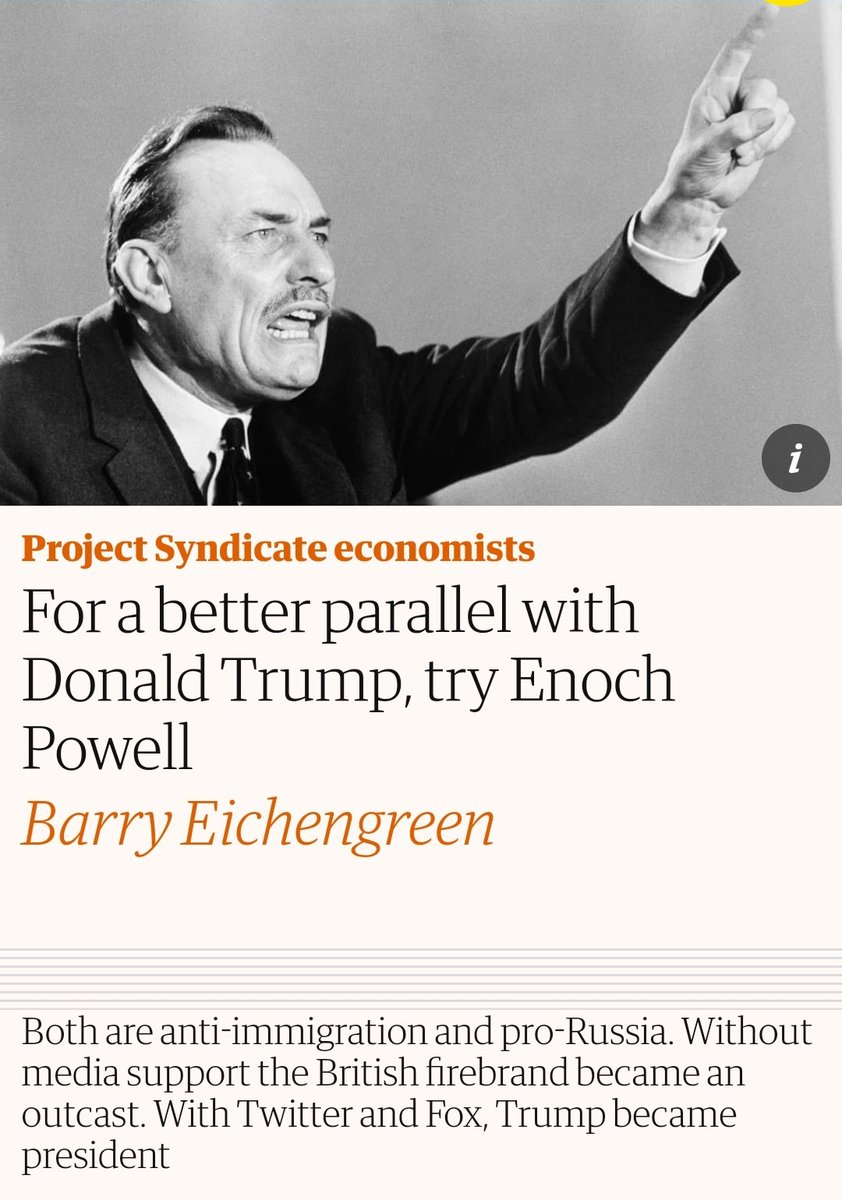

Powell’s “rivers of blood” speech in 1968 led Edward Heath to sack him from his post as defense spokesman in the shadow cabinet.

Later, Powell became a Tory outcast, spending the last decade of his parliamentary career as an Ulster Unionist MP.

Later, Powell became a Tory outcast, spending the last decade of his parliamentary career as an Ulster Unionist MP.

Kenneth Clarke – himself a vivid example of the obsolete: a Europhile Tory – claimed in 2017 that Powell would have been amazed at the extent to which the post-referendum Conservatives, “Euroskeptic and mildly anti-immigrant”, had embraced his ideas.

Enoch Powell was also an opponent of nuclear weapons and the death penalty, convinced for geostrategic reasons of Britain’s common interests with Russia and outspokenly anti-American, as well as a wholly committed supporter of the NHS.

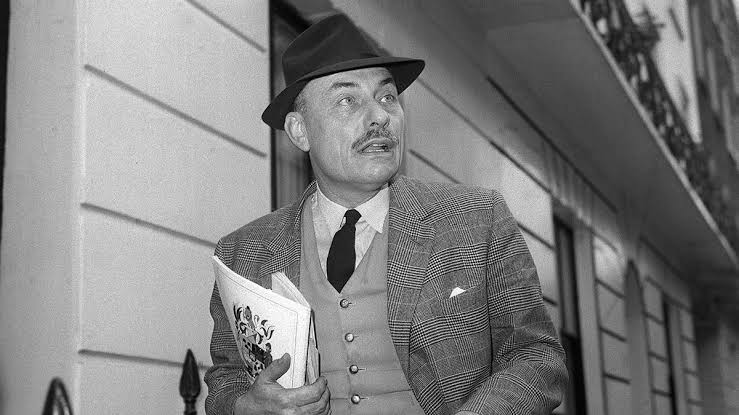

Brought up in the lower-middle-class of the west Midlands, Powell won a scholarship to King Edward’s Birmingham, and then went to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he was the outstanding classicist of his generation.

He became a fellow of Trinity, and then at the age of 25 a full professor of Greek at the University of Sydney: not a matter of pride, but of distress, for Powell’s hero, Friedrich Nietzsche, had become a professor of classics at the age of 24.

Although he voted Labour in 1945 – to punish the Tories for appeasement – Powell soon joined the Conservative Research Department, abandoning academic life, though not the realm of ideas.

He became the MP for Wolverhampton South West in 1950.

He became the MP for Wolverhampton South West in 1950.

Powell and Heath – who was also a clever, Oxbridge-educated, lower-middle-class Conservative with a good war behind him – were rising stars of the party during the 1950s and early 1960s.

However, while Heath was happily conformist, Powell was intellectually restless.

Powell also dissented from Macmillan’s fiscally loose Keynesianism.

Powell also dissented from Macmillan’s fiscally loose Keynesianism.

The furore that followed the rivers of blood speech in 1968 marked the start of a prolonged personal, political and intellectual rupture with Heath, which was a leading theme in Tory politics between 1968 and 1974.

Like Nietzsche, Powell was a deliberate provocateur.

It is hard to tell, with this contrarian who spent most of his political career out of high office and seemed addicted to futile grand gestures, what was policy and what was pose.

It is hard to tell, with this contrarian who spent most of his political career out of high office and seemed addicted to futile grand gestures, what was policy and what was pose.

Powell himself was convinced, after the delusions of empire fell away, that he saw the world straight.

Might his fellow Tories come to see the abiding national interests that remained once one had stripped away the misleading rhetoric of anti-communism?

Might his fellow Tories come to see the abiding national interests that remained once one had stripped away the misleading rhetoric of anti-communism?

By the time of the demise of the Soviet Union and the first Gulf War in 1990-91, Powell saw that Britain’s national interest had been quietly subordinated yet again to American goals.

The Rivers of Blood speech was denounced as evil by no less than The Times.

But it won Powell a dedicated following among working-class voters experiencing hard economic times, discomforted by the “invasion” of their neighborhoods by Asian and Caribbean immigrants.

But it won Powell a dedicated following among working-class voters experiencing hard economic times, discomforted by the “invasion” of their neighborhoods by Asian and Caribbean immigrants.

Powell was a committed nationalist who rejected any & all alliances that threatened British independence.

He implacably opposed joining the EEC on the grounds that doing so would compromise British identity and sovereignty. He left the Conservative party over the issue in 1974.

He implacably opposed joining the EEC on the grounds that doing so would compromise British identity and sovereignty. He left the Conservative party over the issue in 1974.

With the exception of two tabloids, coverage of his Rivers of Blood speech ranged from skeptical to outright hostile.

The BBC ruled the airwaves. Powell had no equivalent of Twitter to spread the word, and there was no Fox News or Breitbart to create an ideological echo chamber.

The BBC ruled the airwaves. Powell had no equivalent of Twitter to spread the word, and there was no Fox News or Breitbart to create an ideological echo chamber.

Even in the economically disastrous 1970s, British voters were not prepared to reject the political status quo.

Discontent and disillusion were not “accompanied by a basic questioning of British political institutions”, in the words of Powell’s biographer, Douglas Schoen.

Discontent and disillusion were not “accompanied by a basic questioning of British political institutions”, in the words of Powell’s biographer, Douglas Schoen.

The 50th anniversary of his notorious “Rivers of Blood” speech against mass immigration in 2018 prompted a deluge of editorials, articles, TV and radio programs, protests and debates.

Some even tried to pin the Windrush scandal over threatened deportations on him.

Some even tried to pin the Windrush scandal over threatened deportations on him.

Powell was a free-trader, but against the free movement of labor.

His “Rivers of Blood” speech was racist in tone, and certainly incited racism (he became a hero to far-right groups), but he was for strict equality before the law.

His “Rivers of Blood” speech was racist in tone, and certainly incited racism (he became a hero to far-right groups), but he was for strict equality before the law.

For Powell, there were no contradictions.

He was a trained classicist, not an economist and for Powell the survival and nourishing of the nation-state was the most important duty of a statesman.

He was a trained classicist, not an economist and for Powell the survival and nourishing of the nation-state was the most important duty of a statesman.

Powell probably would have been a fan of Vladimir Putin; Trump’s “America First” doctrine would doubtless have met with his approval.

UKIP is wholly inspired by Powell, and forced David Cameron into holding the fateful Brexit referendum in 2016.

UKIP is wholly inspired by Powell, and forced David Cameron into holding the fateful Brexit referendum in 2016.

His original arguments against the EEC, that it was an unaccountable bureaucracy making laws with no regard for national parliaments, were exactly those that won the day in June 2016.

“Take back control” would be a fair summary of Powellism.

“Take back control” would be a fair summary of Powellism.

Recent scholarship on Powell has sought to draw out his long-term influence on politics, society and economy beyond the visceral racism that he so expertly conjured, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13563467.2020.1841140

Much of Britain’s governing class promote an ethics of individual risk/responsibility at the same time as paradoxically supporting the ‘people’ in their struggle against ‘elites’.

The same class also subscribe to the notion that needs are best met through individual competitiveness while paradoxically calling for redistributive justice on behalf of the ‘white working class’.

Powell was indeed a believer/promoter of neoliberal policies.

Keith Joseph is considered the key politician through which Thatcher came to channel Milton Friedman’s theory of monetarism.

Powell, though, was Joseph’s senior and knew Friedman through the Mont Pelerin Society.

Keith Joseph is considered the key politician through which Thatcher came to channel Milton Friedman’s theory of monetarism.

Powell, though, was Joseph’s senior and knew Friedman through the Mont Pelerin Society.

There was a fleeting moment when it seemed possible that Keith Joseph would become leader of the Conservative party.

The double general election defeats in 1974 had left the Tories dispirited and directionless.

The double general election defeats in 1974 had left the Tories dispirited and directionless.

Edward Heath did not respond charitably to this innovation: "A good man fallen amongst monetarists. They've robbed him of all his judgment. Not that he ever had much in the first place".

The Conservative party, happily, was spared the leadership of Joseph but was amply compensated by his skills and dedication as the intellectual leader during the opposition years 1975-79.

Keith Joseph was born into an Ashkenazi Jewish family. He remained devoted to the Jewish faith throughout his life.

His father was a self-made businessman, founding the construction company of Bovis, and becoming Lord Mayor of London.

His father was a self-made businessman, founding the construction company of Bovis, and becoming Lord Mayor of London.

After the general election victory of 1979 Margaret Thatcher made Keith Joseph the secretary of state for industry.

It was something of an anti-climax as the department was not a major Whitehall fiefdom.

It was something of an anti-climax as the department was not a major Whitehall fiefdom.

Powell was involved in an early set of exchanges curated by the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) which, by the 1980s, would become the US equivalent to the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA).

English nationhood, Powell argued, had never in any way been modified or changed by Empire: the “nationhood of the mother country remained unaltered through it all, almost unconscious of the fantastic [imperial] structure built around her”.

Such distrust of non-whites is evident as far back as the 1940s when Powell reasoned that Indians were ill-suited for orderly self-government due to their proclivity to vote along communal lines rather than as independent citizens.

No surprise, then, that in Powell’s estimation, the black and brown Commonwealth settler could never ‘become an Englishman’ in the cultural sense: English heredity was defined by orderly independence which demanded a self-responsibility to which communalism was antithetical.

Culture, for Powell, was race.

When speaking of those population groups who did not, in his estimation, wish to integrate, Powell famously proclaimed that “their color marks them out”.

When speaking of those population groups who did not, in his estimation, wish to integrate, Powell famously proclaimed that “their color marks them out”.

Powell’s defense of an altruistic domain for social services was not made on ethical grounds – via the principle of universal provision – but on racial grounds – on behalf of preserving the purity of English heredity.

Powell conceived of what we now call ‘neoliberal subjectivity’ in terms of a defense of English heredity – a heritage founded on the principle of orderly independence.

Thatcher was far more of a status quo pragmatist than Powell ever was.

But even so, Powellism clearly laid the ideational and electoral groundwork for Thatcherism.

But even so, Powellism clearly laid the ideational and electoral groundwork for Thatcherism.

Powell fell in love with India, and led him to dream of becoming its Viceroy, to which end he added Urdu, Hindi and Punjabi to the dozen languages he spoke, eight of them fluently.

India’s independence therefore came as a shattering blow to Powell. https://unherd.com/2020/09/would-enoch-powell-have-supported-brexit/

India’s independence therefore came as a shattering blow to Powell. https://unherd.com/2020/09/would-enoch-powell-have-supported-brexit/

Walking London’s streets alone the night Britain’s relinquishment was announced, struggling to come to terms with the significance of the moment for his beloved country and the Empire, Powell himself became one of India’s troubled Midnight’s Children.

The loss of India and Britain’s consequent diminished place in the world became the central pole of Powell’s worldview.

The bloodshed of Partition fuelled his later fears both of mass immigration and of civil war in Northern Ireland.

The bloodshed of Partition fuelled his later fears both of mass immigration and of civil war in Northern Ireland.

Powell argued just after the fall of Singapore in 1942, that to maintain strategic independence from US “it was in the British interest to preserve its naval strength through means not short even of alliance with Japan,” otherwise “Empire would only exist on American sufferance.”

His intense loathing of “our terrible enemy” the US was one of the few constants of his political career.

His early realization that America’s rise would mean Britain’s total strategic subordination was shrouded from public view by the comforting fiction of equal partnership.

His early realization that America’s rise would mean Britain’s total strategic subordination was shrouded from public view by the comforting fiction of equal partnership.

There is something Gaullist in Powell’s distaste for the US, and the urgency to maintain UK independence from it.

By the time of the Vietnam War, Powell “argued that Britain had lost the ability to distinguish between an ally and a satellite, or between a friend and a lackey.”

By the time of the Vietnam War, Powell “argued that Britain had lost the ability to distinguish between an ally and a satellite, or between a friend and a lackey.”

For Powell, there was little to choose between the two, and “no reason to believe that the British constitution will be threatened more by the socialist dictatorship than by the democracy of the United States”.

Praising de Gaulle for pulling France out of NATO, Powell foreshadowed the French strongman’s modern heir Macron in eyeing Russia as the counterweight to preserve his own nation’s strategic autonomy.

Powell’s High Tory British nationalism, focused on defending Britain’s place in the world as a sovereign power rather than an American client state, put him at odds with the Conservative Party mainstream.

By 1992, “Powell had developed his position into a full blown critique of the ‘new world order’, a term that had gained increasing usage to describe the hegemonic position of the United States”.

A fierce critic, post-Suez, of Britain’s residual imperial pretensions, Powell initially viewed the nascent European Community as a means to preserve Britain’s autonomy within a Europe of Nations, approvingly citing de Gaulle’s analogous vision.

Powell’s devotion to Parliament and the Crown as the repository of Britain’s national soul indicates, perhaps more clearly than anything else, the sharp distinction between his idealist political vision and the caricature of him as a rabble-rousing populist.

Even in his incarnation as an Ulster Unionist MP, Powell displayed no malice for Irish nationalism, at least in the Republic, while fiercely opposing its expression in the island’s six northern counties as a threat to the political sovereignty of the Protestant then-majority.

“England will never again consent to live through the long and harrowing episode of the coercion of the Irish,” he declared when drawing parallels to the nascent nationalisms of Scotland and Wales, because “enforced unity is a curse.. any consequence or condition is preferable.”

Powell’s positions on both the internal configuration of the nation state and its external relations were intertwined, and were applied by him on a fairly consistent basis throughout his career, https://academic.oup.com/tcbh/advance-article/doi/10.1093/tcbh/hwaa022/5864477

The Black Lives Matter movement has accelerated a reckoning across Europe about the legacies of slavery and imperialism, nowhere more urgently than in Britain,

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/11/02/misremembering-the-british-empire

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/11/02/misremembering-the-british-empire

The Labour Party has pledged to “ensure the historical injustices of colonialism, and the role of the British Empire” are “properly integrated into the National Curriculum,” while Boris Johnson decries a “cringing embarrassment about our history.”

Unlike most other European countries, Britain stops requiring students to study history when they reach the age of fourteen, which leaves little room for nuance in a national curriculum designed to showcase “our island story.”

British views of empire remain “hostage to myth” partly because historians made them so.

In 1817, James Mill provided a template when he published his three-volume “History of British India,” which became a textbook for colonial administrators.

In 1817, James Mill provided a template when he published his three-volume “History of British India,” which became a textbook for colonial administrators.

“In the end, the British sacrificed her Empire to stop the Germans, Japanese and Italians from keeping theirs,” Niall Ferguson wrote in 2002.

“Did not that sacrifice alone expunge all the Empire’s other sins?”

“Did not that sacrifice alone expunge all the Empire’s other sins?”

Twelve days before Malaya’s independence, in 1957, British soldiers in Kuala Lumpur loaded trucks with boxes of records to be driven down to Singapore and, a colonial official reported, “destroyed in the Navy’s splendid incinerator.”

In 1961, recognizing that “it would perhaps be a little unfortunate to celebrate Independence Day with smoke,” the Colonial Office advised the governor of Trinidad and Tobago that he could also pack files into weighted crates and drop them into the sea.

By eliminating written evidence of their actions from the archival record, British officials sought to manipulate the kinds of histories that future generations would be able to produce.

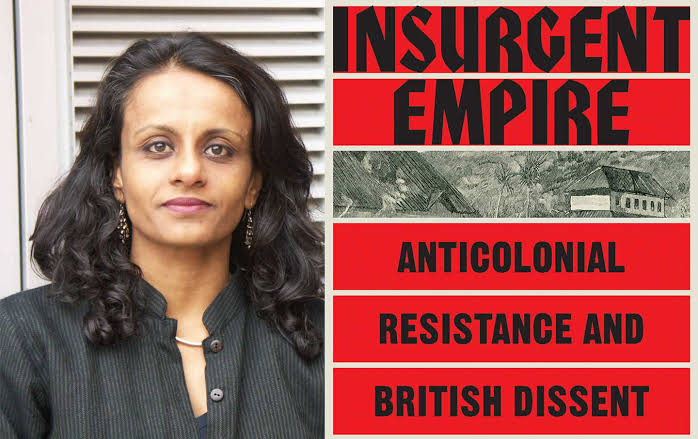

A fuller history of empire and its legacies requires, in part, what the Cambridge academic Priyamvada Gopal calls “a sustained unlearning.”

Colonial officials in Uganda, rifling through their files to figure out what to destroy, came up with a name for the process of erasure. They called it Operation Legacy.

In 2011, in the course of negotiations with former Kenyan detainees, the British government announced that it had in its possession some secret files outside the regular classification system. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03086534.2017.1294256

Henry Moore failed the Indian Civil Service examination, and therefore joined the Ceylon civil service.

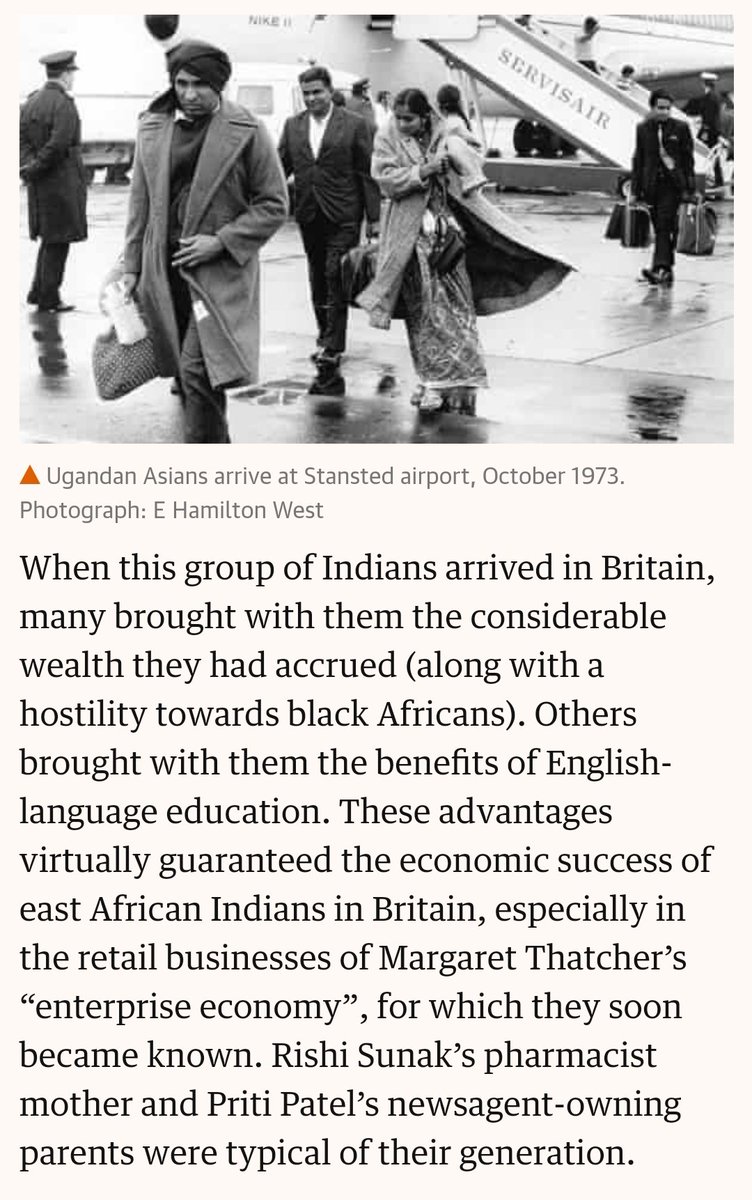

The first wave of Indian migration was in the late 1940s and 50s, when migrants were recruited directly from India to fill the labor shortage.

The second wave were the so-called “twice migrants” who arrived from east Africa in the 1960s and 70s. https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/27/how-did-british-indians-become-so-prominent-in-the-conservative-party

The second wave were the so-called “twice migrants” who arrived from east Africa in the 1960s and 70s. https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/feb/27/how-did-british-indians-become-so-prominent-in-the-conservative-party

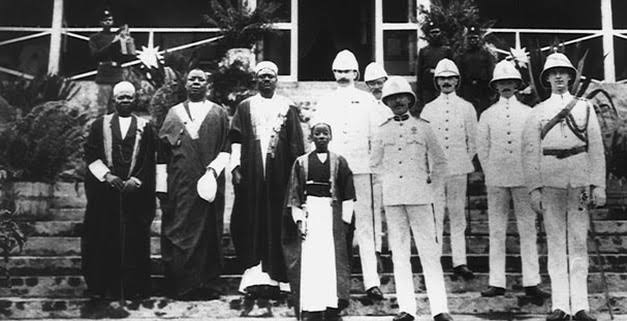

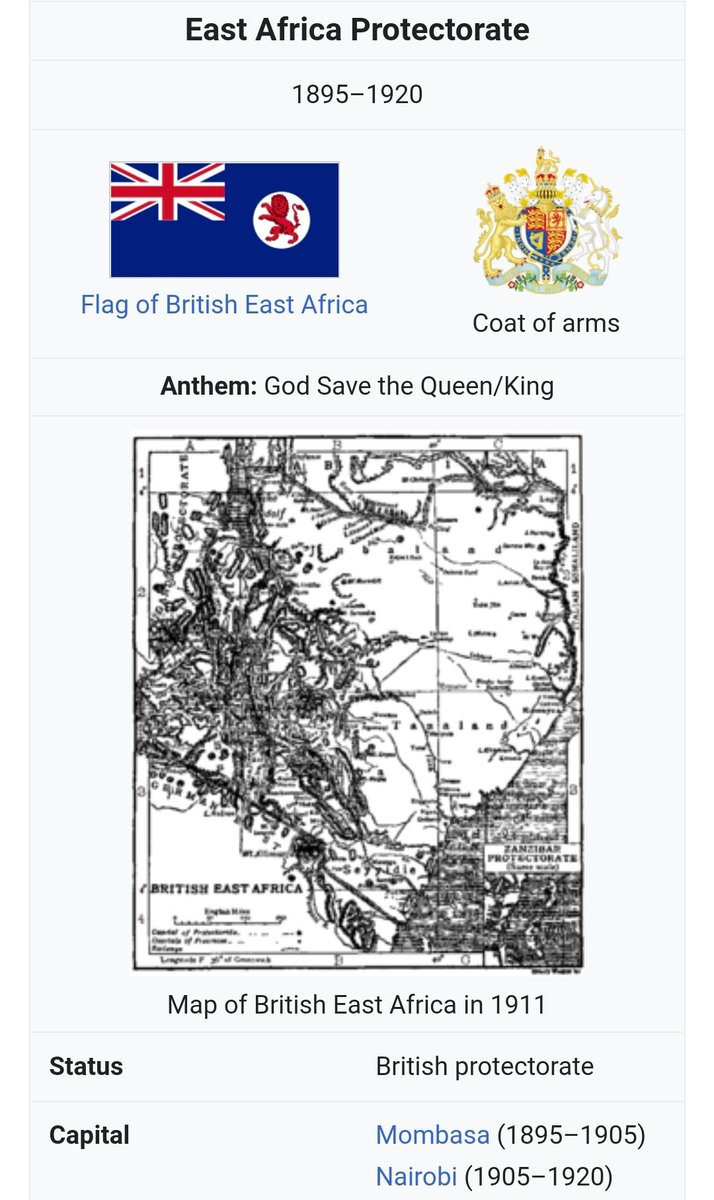

In 1895, with the creation of the British East Africa Protectorate, British officials envisioned the protectorate, which occupied roughly the same area as modern-day Kenya, as the “America of the Hindu”, a settler-colonial project to be led by Indians on behalf of the British.

In the early 20th century, thousands of Indians (mostly Goans, Gujaratis and Punjabis) were imported into east Africa as sub-colonial agents of civilization.

They were required to work in colonial administration and serve in the colonial police and army, to keep the “native peoples” in order.

At the same time, more than 30,000 indentured laborers were brought over from India to build the Kenya-Uganda railway.

At the same time, more than 30,000 indentured laborers were brought over from India to build the Kenya-Uganda railway.

Functioning as a subordinate ruling class, Indians in east Africa enjoyed success in business, finance and the professions throughout the colonial period, and gained significant control over the economy.

Rishi Sunak’s pharmacist mother and Priti Patel’s newsagent-owning parents were typical of their generation who arrived in Britain from east Africa.

From the 1980s onwards, the Tories began to court an imagined “Indian community”, limited to east African Indians who had settled around London.

Labour is painted by them as “anti-Hindu” and pro-Muslim, citing Labour’s perceived support for the Kashmiri struggle for self-determination as evidence.

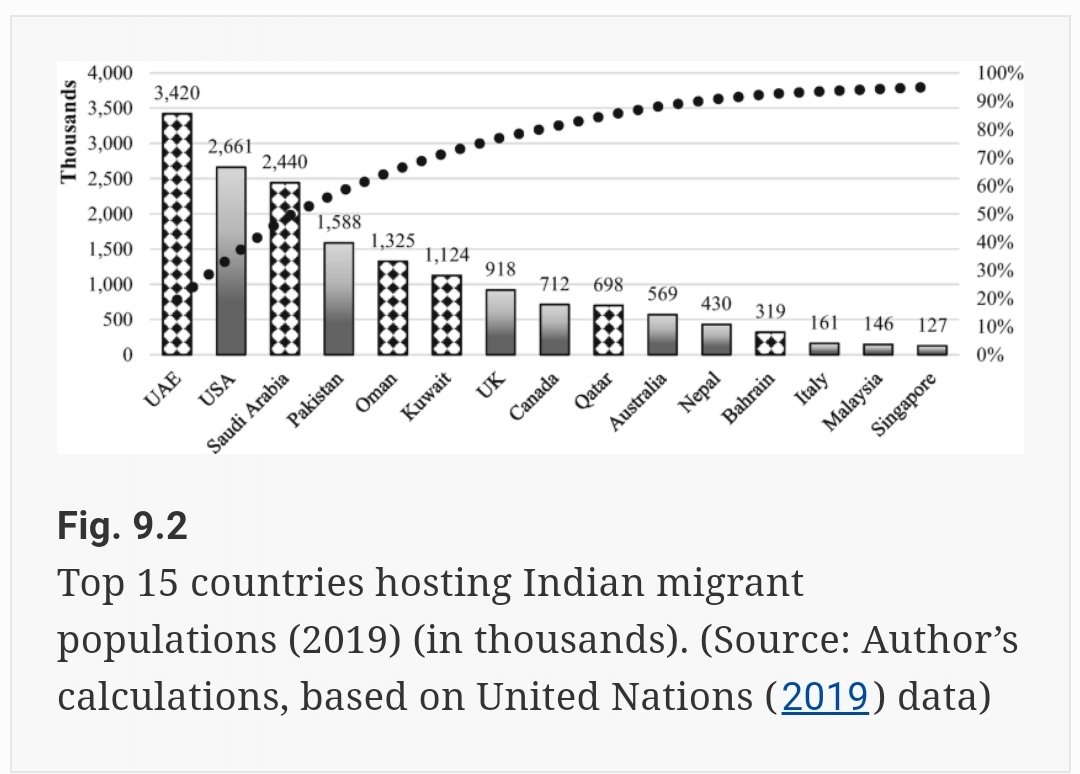

India not only has the largest emigrant population in the world. The country also has a long history of establishing an institutional framework and a multi-faceted infrastructure for its diverse diaspora populations. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-51237-8_9

The Indian government estimates that in the end of 2018, out of 31 million overseas Indians, 13 million were NRIs and 18 million PIOs.

New Delhi revised and institutionalized the relationship with India’s influential diaspora spread across the world in an effort to redesign its global image as a serious economic player and technological powerhouse.

In 2004, India established a special Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs (MOIA) that had different joint secretaries and divisions to cater to different categories of overseas Indians.

In 2015, the Modi government merged the MOIA with the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), where the bulk of issues related to diaspora and NRI affairs are handled now at the ministerial level.

As India has a decentralized structure of federal governance, some of India’s states also created institutional and regulatory frameworks for diaspora and migrant populations.

India’s first ambassador to East Africa Apa Pant was the son of the ruler of the princely state of Aundh during British Raj.

Before Indian independence, Pant had already served as Education Minister and Prime Minister of Aundh under his father's tutelage.

After Apa Pant returned home from his studies in England, Maurice Frydman, a Polish Jew who converted to Hinduism, urged him to give up all power to the people as part of the Aundh Experiment.

Pant told Nehru that he knew nothing of diplomacy, or of Africa.

“Never Mind”, Nehru said jokingly, “Go and shoot a few lions!”

“Never Mind”, Nehru said jokingly, “Go and shoot a few lions!”

The numbers of people of Indian descent at end of 1952 were estimated as:

Kenya: 152,000;

Uganda: 33,367;

Tanganyika: 56,499;

Zanzibar and Pemba: 15,812;

Northern Rhodesia: 2,600;

Southern Rhodesia: 4,150;

Nyasaland: 4,000.

Kenya: 152,000;

Uganda: 33,367;

Tanganyika: 56,499;

Zanzibar and Pemba: 15,812;

Northern Rhodesia: 2,600;

Southern Rhodesia: 4,150;

Nyasaland: 4,000.

Due to rising racial tensions in the 1930s, then Colonial Secretary Ormsby-Gore once said that he regarded Indians as “mere interlopers in a country that belonged only to Africans and Europeans”.

The East African Indian National Congress (EAINC), formed in 1914, called for equality between Indians and Europeans, advocating the inclusion of Indians on the same roll as Europeans in elections and that Asians be allowed to farm in the White Highlands.

From before the Great War until the early 1920s, East Africa was the focus of an especially bitter battle between Asian and European settlers to determine the nature of colonial government and the future political development of the region.

The struggle for East Africa coincided with important changes both in Africa and in India.

Although the war granted new opportunities for Indians and the Indian government, it also created a host of new challenges and dilemmas.

Although the war granted new opportunities for Indians and the Indian government, it also created a host of new challenges and dilemmas.

The prospect of an Indian colony in the former German East Africa and the campaign to achieve equal rights for Asians in Kenya posed particular problems for the Indian government at home and abroad.

Related,

British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East

edited by James R. Fichter

https://books.google.com/books?id=NR2nDwAAQBAJ

British and French Colonialism in Africa, Asia and the Middle East

edited by James R. Fichter

https://books.google.com/books?id=NR2nDwAAQBAJ

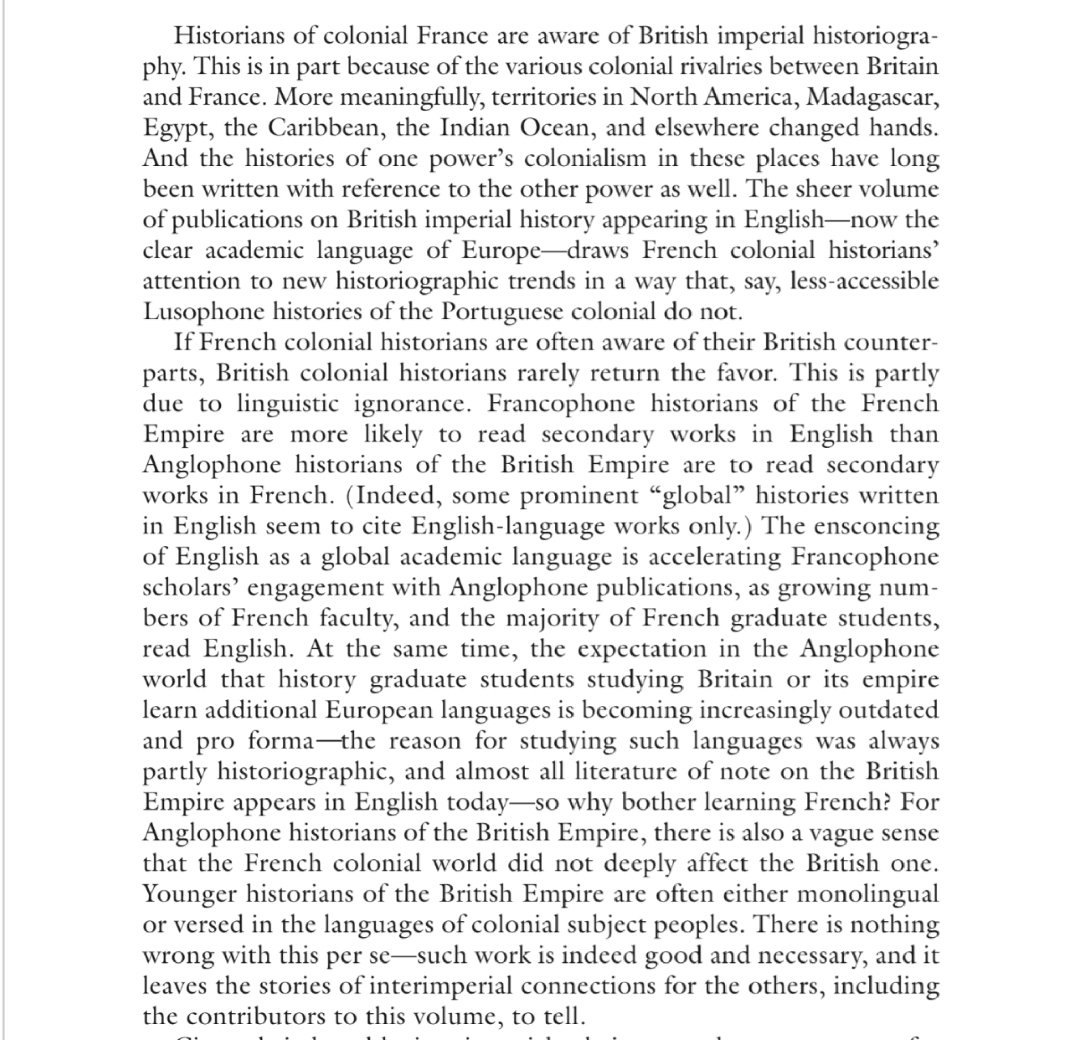

For Anglophone historians of the British Empire, there is a vague sense of the French colonial world didn't deeply affect the British one.

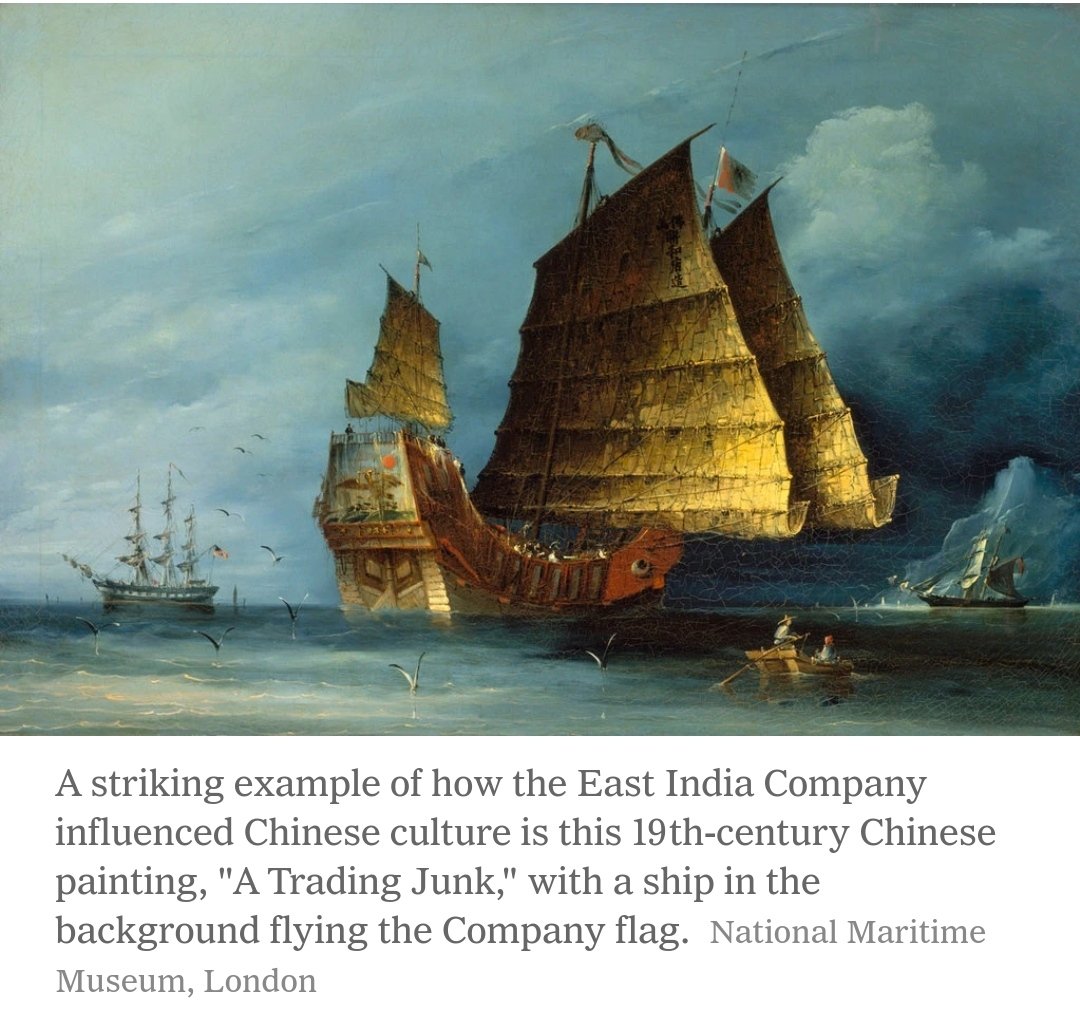

The British East India Company was competing in an arena that was already dominated by Arab, Ottoman, Portuguese and Dutch fleets. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/05/arts/05iht-rarteast05.html

Pant also served as Nehru's point person for China-related special duties in Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet (after the flight of the Dalai Lama), followed by full ambassadorships in two key non aligned countries (Indonesia under Sukarno and Egypt under Nasser).

“Sir Harry Johnston (1858-1927) once expressed the opinion that East Africa ought to be the America of India.”

https://books.google.com/books?id=ZvAoasZjI8wC&pg=PA178&dq=America+of+the+Hindus+East+Africa+Protectorate

https://books.google.com/books?id=ZvAoasZjI8wC&pg=PA178&dq=America+of+the+Hindus+East+Africa+Protectorate

“I gladly testify to the cordial spirit of cooperation which the German authorities have always shown.”

Eliot also served as British Ambassador to Japan in 1919–1925 and wrote a book about Japanese Buddhism.

https://books.google.com/books?id=N3oRI23AdkkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://books.google.com/books?id=N3oRI23AdkkC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter