“Xi’s swift reversal of more than three decades of apparent movement toward collective leadership and a less intrusive party has surprised both U.S. officials and much of the Chinese elite.” https://www.wsj.com/articles/xi-jinping-globalist-autocrat-misread-11608735769

“People who speak with him or study his record say his time in the village was transformative.

They say he developed an affinity and sense of duty to China’s rural poor, and a pragmatism through dealing with village life.”

They say he developed an affinity and sense of duty to China’s rural poor, and a pragmatism through dealing with village life.”

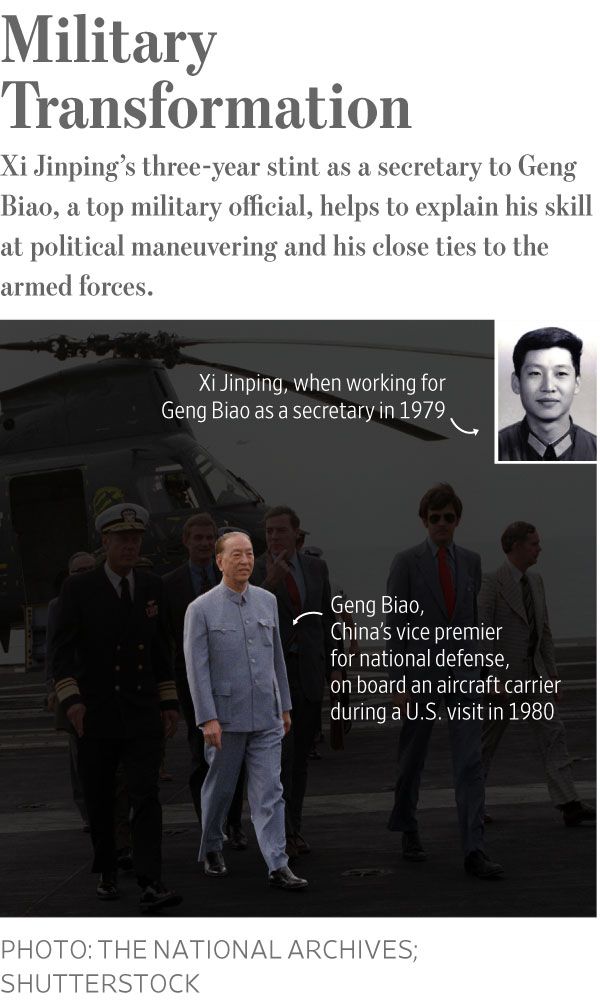

While serving as the secretary to then defense minister Geng Biao, he gained an inside view of U.S.-China relations, learning to see the U.S. as both a partner and a potential threat.

Geng was an army veteran who had served with Xi’s father, been ambassador to six countries and led the International Liaison Department, which managed ties with Communists abroad.

Geng was demanding and security-conscious, insisting that Xi memorize meetings’ proceedings rather than take notes.

To this day, Xi memorizes large portions of speeches and rarely uses notes in private meetings.

To this day, Xi memorizes large portions of speeches and rarely uses notes in private meetings.

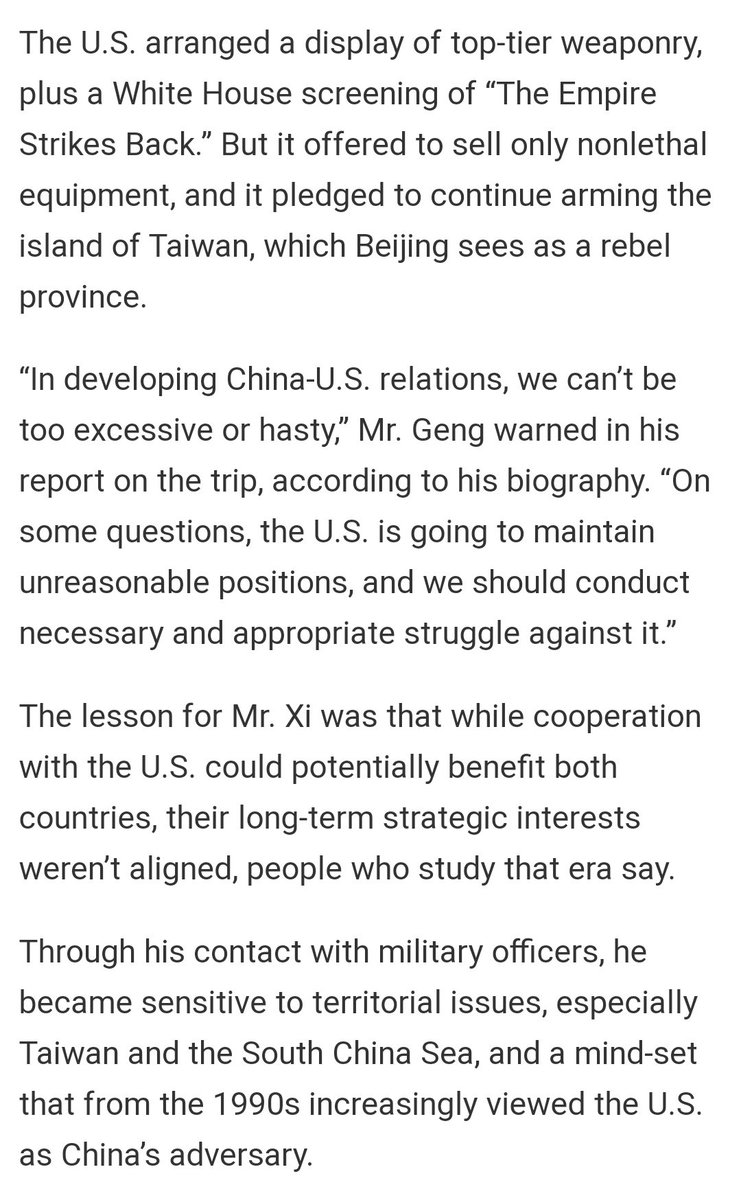

The lesson for Xi was that while cooperation with the U.S. could potentially benefit both countries, their long-term strategic interests weren’t aligned.

Following his promotion in 2007 to the Politburo Standing Committee, he was increasingly exposed to a debate between advocates and opponents of liberalization.

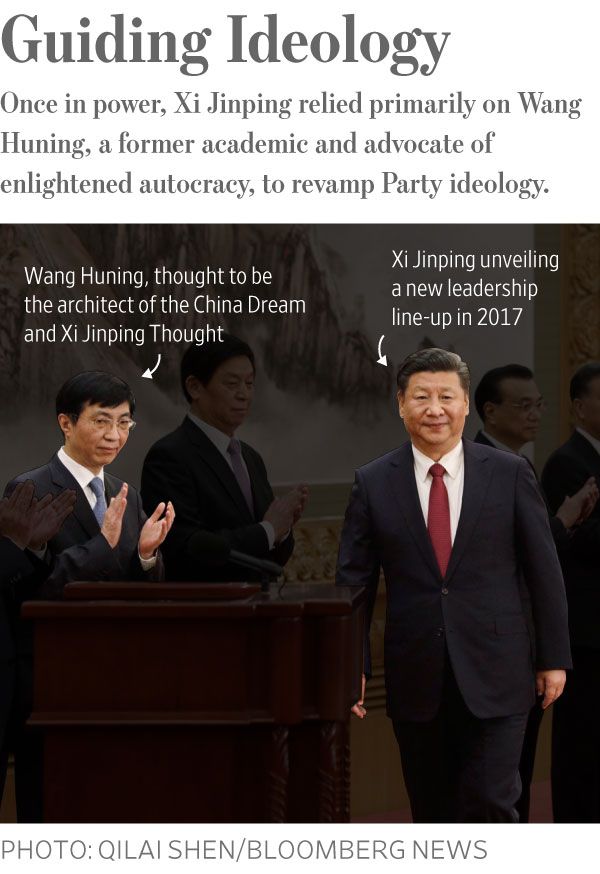

That’s when he got to know Wang Huning, a former academic who became his top political adviser.

That’s when he got to know Wang Huning, a former academic who became his top political adviser.

Jude Blanchette: If we want to understand the ultra-conservative political moment China is now in, we need to understand Wang Huning’s theory of “neo-authoritarianism,” http://www.judeblanchette.com/blog/2017/10/20/wang-hunings-neo-authoritarianism-dream

As he watched the atrophy of Beijing’s authority increase along with the reforms, Wang Huning worried that if the decentralization of power continued apace, it would usher a return to a “feudal economy”.

In a August 1988 article, Wang warned of China being split into “30 dukedoms, with some 2,000 rival principalities" owing to the decentralization of authority following reform.

This was to become one of the central questions as Beijing navigated its post-Mao era: how to balance openness (of ideas, goods, and people) with the requisite political control needed to ensure stability and, most importantly, its monopoly on power.

To begin with, Wang argued, one needed to look past the reform-era mentality of seeing the principle struggle as one between the government on the one hand and the market (or enterprises, 企业) on the other.

Wang’s writings of the 1980s were to form the foundation of what came to be known as “neo-authoritarianism” (新权威主义).

One poll from 1988 reported that 60% of respondents felt the reforms were moving “too fast,” up from 20% in 1987.

Look at the first five years of Xi’s administration through the neo-authoritarian lens, and we see a consistent theme: clawing power back to Beijing.

"In both north and south China, memories of the Mao era (real and imagined) powered a sense of grievance and opposition."

https://books.google.com/books/about/China_s_New_Red_Guards.html?id=jNmUDwAAQBAJ

https://books.google.com/books/about/China_s_New_Red_Guards.html?id=jNmUDwAAQBAJ

"Westerners made the mistake of talking only to those they liked or those who thought China was doomed."

These debates speak to deep divisions running through Chinese society, despite the outward appearance of political stability.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter