Alright, so here is the next thread in my series on the French army in the 18th century. Today we will be covering the first years of the War of the Spanish Succession. I really enjoyed making this and I hope you all will enjoy it too.

For the diplomatic background on the war check out my previous thread. I’ll do a small recap on who’s involved in a bit, but not the reasons each country is fighting on their respective side or the causes of the war. https://twitter.com/JasonLHughes/status/1316120326267338753?s=20

A few notes before we start the thread. I will be saying British instead of English for this thread, despite England and Scotland only being unified in 1707. I’m doing this for the sake of continuity and simplicity, despite the adjective being inaccurate for some of the period.

Also, I will not be able to cover everything in the War of the Spanish Succession; the conflict is far too large to cover fully on Twitter. Instead, I will try to provide an overview with examples that demonstrate the development of France’s military doctrine and reputation.

There were four main theaters of the war: the Spanish Netherlands/Flanders, the Rhine/Bavaria, Northern Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula. There was also a connected independence war in Hungary and a colonial war in North America.

Rákóczi's War of Independence in Hungary lasted from 1703 to 1711 and consistently drew Austrian troops and resources away from the conflict with France. The rebellion was funded by the French; however, it was never organized enough and was eventually defeated.

The colonial war in North America is usually called Queen Anne’s War. While certainly more eventful than King William’s War, basically all you need to know for our purposes is that France lost Arcadia and a few other Canadian territories. Alright, so now back to the war proper.

Before we begin, please look at this thread on warfare in the 18th century if you haven’t already. I was going to pack all of that into this thread, but I figured that would be pretty annoying and take up way too much space. https://twitter.com/JasonLHughes/status/1327712410975793155?s=20

Hostilities first began in 1701 (about a year before the widening of the war), with 30,000 Austrian soldiers under Prince Eugene of Savoy crossing the Alps into Northern Italy to confront French forces that had garrisoned Spain’s Italian lands (particularly Milan and Mantua).

Eugene of Savoy was one of the best commanders of the war and he easily outmaneuvered larger French forces under Catinat and Villeroy (Catinat’s successor) and defeated them at the Battles of Carpi and Chiari respectively. Eugene even engaged in a winter campaign in early 1702.

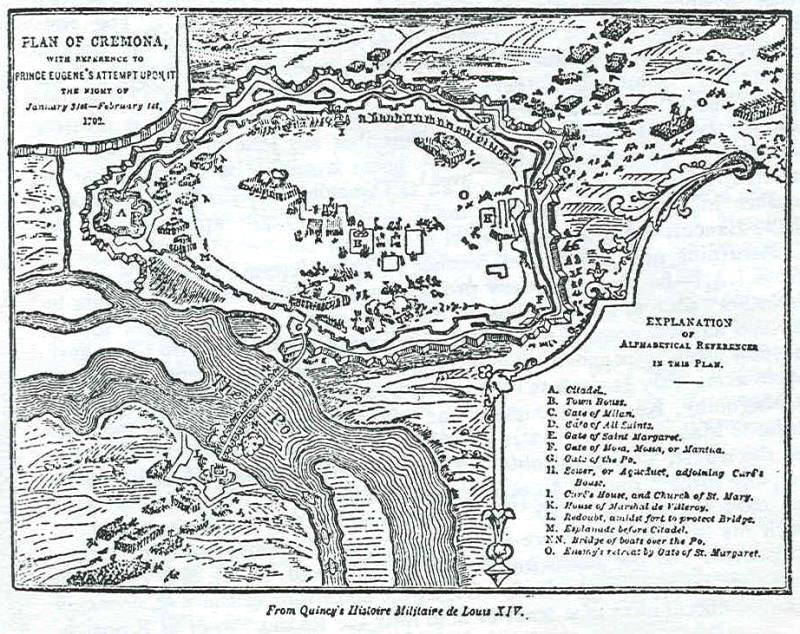

This unusual winter offensive achieved complete surprise and Villeroy was captured at Cremona. However, two regiments of the Irish Brigade managed to salvage the situation and held Eugene off until reinforcements arrived. They lost 350 out of 600 men engaged.

Despite the bravery of the men of the Irish Brigade, the French were pushed back across the Adda and the situation in Italy looked grim for France. Eugene’s victories in Italy solidified Anglo-Dutch support for the Hapsburg cause and led to their entry into the war in May.

Italy was initially the main focus of the war, and Louis XIV accordingly sent one of his best generals, Vendôme, to Italy with substantial reinforcements. Vendôme, unlike Villeroy, was able to take advantage of his numerical superiority and outmaneuver Eugene.

Eugene, desperate to regain the initiative and preserve his supply lines, made a determined assault at Luzarra that was repulsed after bloody fighting. Vendôme had lost more men than Eugene and the battle was basically a draw, but Vendôme had salvaged the situation in Italy.

Most of the former Spanish lands in northern Italy had been regained, and the embarrassments of the previous year had been dampened somewhat by Vendôme’s well-run campaign. However, 1701’s embarrassments were just portents of what was to come.

Meanwhile, the war in Flanders and along the Rhine had begun to develop. Marlborough, the best general of his age, had arrived in the Netherlands to take command of allied forces. In the campaign season of 1702, he managed to retake the barrier fortresses and capture Liège.

However, these successes were hampered by a lack of Dutch cooperation and Marlborough was not able to seriously compromise the massive trenches and redoubts that formed the Lines of Brabant, which shielded most of the Spanish Netherlands from allied incursions.

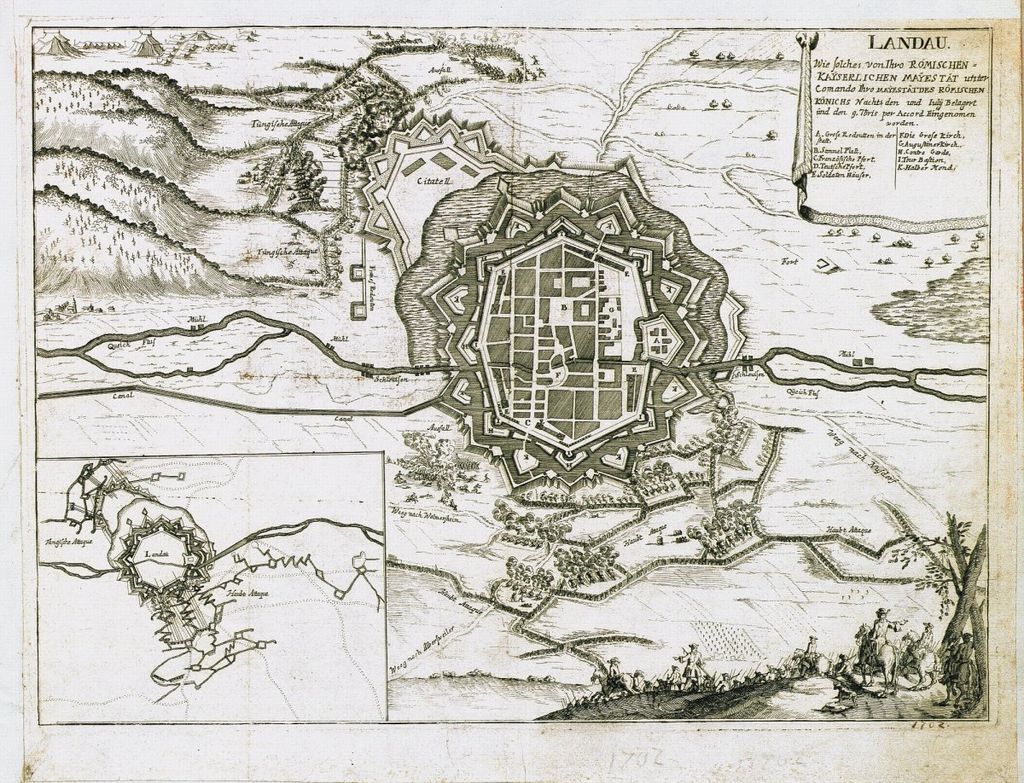

The situation along the Rhine was looking better for the French. The vigorous defense of Landau by its garrison held down Imperial forces in the region while Villars, one of the best generals of the war, was sent east to aid France’s new ally, Bavaria (ruled by Maximilian II).

Maximilian managed to take Ulm via a coup de main (direct assault) in September and Villars defeated Imperial forces at Friedlingen in October. These two victories opened a corridor between the French and Bavarian forces, which would have dramatic consequences in 1703 and 1704.

Actions in the Spanish peninsula were limited to a failed attempt by Anglo-Dutch forces to take Cadiz after an amphibious landing. The Anglo-Dutch navy did score a victory at the Battle of Vigo Bay, which contributed to Portugal joining the Grand Alliance in 1703.

An issue of some concern to Louis XIV in 1702 was the Camisard uprising by protestants in south-central France. While it did not have a large impact on the war, the uprising was notable for the brutality displayed on both sides. The uprising was largely crushed by 1704.

1703 was probably the best year for France during the entire War of the Spanish Succession (at least until the final year or so of the conflict). By the end of the year, it seemed like complete victory was just one campaign season away.

In Flanders, Marlborough’s ambitious plans to take Antwerp were rejected by the understandably risk-averse Dutch government and its generals. Nonetheless, Marlborough managed to take Bonn, Huy, and Limburg, slowly taking bites out of the French defensive line.

The only major battle of the season in Flanders was at Ekeren, where a diversionary Dutch force of 10,000 men under General Obdam was surrounded by around 20,000 French and Spanish soldiers. The battle had no strategic impact but it’s interesting, so I’ll spend some time on it.

Obdam’s force had been caught off-guard by the rapid consolidation of Boufflers’ Franco-Spanish forces near Antwerp, with one French contingent marching 30 miles in a single day. Boufflers was able to cut off Obdam’s escape with a force of dragoons. (BRB, ran out of thread lol)

Fierce fighting ensued, with French forces trying to tighten the cordon and destroy the outnumbered Dutch contingent. French attacks were repulsed with heavy losses while Dutch officers tried to find a way out of their grim situation. By afternoon Obdam had fled the field.

Obdam’s subordinates (namely Slagenburg) were made of sterner stuff and maintained their men’s discipline. Many Dutch units ran out of ammunition and resorted to the bayonet to claw their way out of the encirclement. By nightfall Slagenburg had forced his way out of the cordon.

Casualties on both sides were horrendous, with the Dutch force losing a fourth of its men (though more French soldiers were killed). The battle had been a French operational success, but the Dutch force had managed to escape destruction due to the iron discipline of its infantry.

In Spain things were quiet, with Philip V reforming the Spanish administration and military to prepare it for the expected Allied onslaught. The only event of note in the Peninsula was Portugal joining the Grand Alliance, giving Allied troops a base for operations in Spain.

Italy, unlike the previous years of the conflict, was quiet for most of 1703. Eugene was recalled to Vienna to deal with the stuff we’ll get to in a bit, and Vendôme made a half-hearted move on Trent (for reasons we’ll also get into in a bit).

The only event of note in Italy during 1703 was the betrayal of Savoy/Victor Amadeus II, which went over to the Grand Alliance while Vendôme was marching on Trent. However, Vendôme quickly returned to Lombardy, disarmed the Savoyard army, and besieged Turin.

The most consequential events of 1703 occurred in southern Germany and along the Rhine. The campaign season began with Villars seizing Kehl, providing a secure bridgehead across the Rhine. Villars then linked up with the forces of Maximilian Emanuel, the elector of Bavaria.

Villars proposed to the elector that Franco-Bavarian forces march directly on Vienna, which he believed would compel the Emperor to sue for peace. He was probably correct, with (unbeknown to him) Rákóczi's rebellion drawing Imperial troops east.

Initially Maximilian reluctantly agreed to this plan, but Louis XIV soon sent word that Villars was to be under the elector’s command and Maximilian decided upon an advance towards the Tyrol to secure Bavaria’s flank. This led to Vendôme’s aforementioned advance towards Trent.

The slowness of Vendôme’s advance collapsed Maximilian’s already ill-conceived plan and wasted valuable months. Instead of returning to Villar’s more aggressive plan, Maximilian tried to attack/besiege Augsburg, which contained the sizeable army of Louis of Baden.

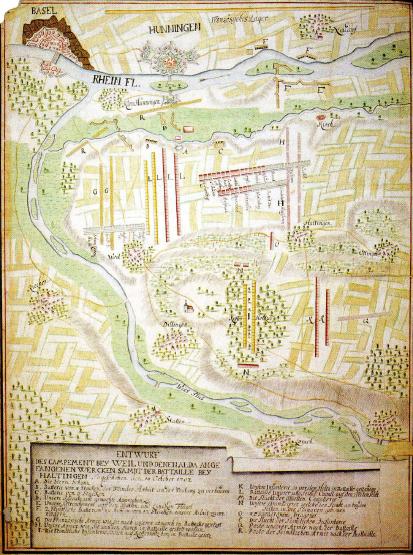

Nonetheless another army under Tallard and the Duke of Burgundy took Bresiach and Landau, securing the Rhine for France. They also decisively defeated a larger Imperial army at the Battle of Speyer in November. In 1704 Tallard’s army was free to march to Bavaria.

Meanwhile, an Imperial army under Count Styrum attempted to join up with Louis of Baden at Augsburg, however they were intercepted at Hochstadt. Villars and Maximilian managed to cooperate and fall on Styrum’s exposed flank and devastate the Imperial army.

Only a brave rearguard action by Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau saved the Imperial army from complete disaster. Nonetheless, the Imperial army lost 11,000 out of 20,000 men. Maximilian once again ordered an advance on Augsburg, but Baden’s defensive position was too strong.

This failure led to even more acrimony between Maximilian and Villars, and Villars was accordingly replaced by the more diplomatic Count of Marsin. Perhaps Villars could have prevented the disasters of 1704, but, in the meantime, he retired to Versailles in disgrace.

Overall, 1703 had been a good year for France. Northern Italy, Flanders, and Spain remained under Bourbon control while Bavarian forces had united with the French army. Hungary was in open revolt, and it seemed that Vienna was within France’s grasp. Victory seemed assured.

Unfortunately, the very dramatic events of 1704 will have to wait for our next thread, which will likely contain the battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, and (hopefully) Oudenarde. There will probably have to be a third thread covering the final years of the war.

If there are any takeaways from the first three years of the conflict, it’s that, when properly led, the French army was still a formidable opponent. French logistical and operational advantages could still overcome France’s enemies. Before 1704 France’s reputation seemed intact.

I will hopefully return soon with the next part of the thread. If you’ve read this far, thank you so much and feel free to follow me if you don’t already.

@threadreaderapp unroll

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter