The ACCC rejected the insufficient conditions w/ which DG Comp cleared Google-Fitbit. The EC decision shows a lack of courage and a refusal to learn from past mistakes. Having worked for months w/ @Caffar3Cristina trying to explain why, it’s time to put down a final marker. 1/

This is a (long) thread in four parts:

I.The Problem with Google

II.Google-Fitbit in a time of Digital Platform introspection

III.Google-Fitbit Theories of Harm

IV.The remedies are insufficient

2/

I.The Problem with Google

II.Google-Fitbit in a time of Digital Platform introspection

III.Google-Fitbit Theories of Harm

IV.The remedies are insufficient

2/

PART I: The Problem with Google.

We’ll start by agreeing that Google makes some great products. (That’s not the problem.) It claims: 3/

We’ll start by agreeing that Google makes some great products. (That’s not the problem.) It claims: 3/

To see this, divide Google’s product history into three parts. Part 1 is “Google as Traditional Media Company”. They launch Desktop Search (1998) and acquire YouTube (2006). Both are free services, monetized by advertising.

5/

5/

Part 2 is “Google as Data Company.” Google launches Gmail (2004), Maps (2005), News (2006), & Chrome (2008). All are “free,” but not monetized directly. (“If you’re not paying for it, you’re the product.”) They generate data: demographic, location, and interest data.

6/

6/

Google also buys Android (2005). This time “free” to consumers and handset manufacturers, giving data from all a user’s smartphone apps. (Also leveraged to protect their Search dominance the goose that laid 2 golden eggs)

7/

7/

Part 3 is Google as Ad Tech monopolist. Google buys Doubleclick (2008) and AdMob (2010), eventually becoming dominant in markets representing advertisers, publishers, and the exchanges that match them to each other. 8/

Google is often dominant in each of the (many) product markets listed above. In part it’s because they make good products and the economic fundamentals favor winner-take-most outcomes (e.g. economies of scale, network effects). But it’s also in part due to…

9/

9/

… leveraging their dominance to foreclose competitors in adjacent markets. Examples include EC’s Google Android case ( https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4581), EC’s Google Shopping case ( https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_17_1784), and US State AG’s Ad Tech case ( https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/news/releases/ag-paxton-leads-multistate-coalition-lawsuit-against-google-anticompetitive-practices-and-deceptive#.X9pyvVvtRG4.twitter). 10/

Google’s businesses allow three (current) monetization strategies.

1.Have dominant audiences to sell to advertisers (Search/YouTube)

2.Have dominant data to target online ads

3.Dominate the ad tech “stack” (operate on all sides, learn WTP, and extract it)

11/

1.Have dominant audiences to sell to advertisers (Search/YouTube)

2.Have dominant data to target online ads

3.Dominate the ad tech “stack” (operate on all sides, learn WTP, and extract it)

11/

The 1st is “normal” market power, but the 2nd & 3rd allow discriminatory market power. Thus the CMA found Google has an “unassailable advantage” in UK search advertising, charging prices 30-40% higher than Bing on like-for-like search terms. ( https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/online-platforms-and-digital-advertising-market-study) 12/

“The Problem with Google” is that:

1. It has very significant (often discriminatory) market power in five markets (Search, YouTube, Android, Ad Tech, and Data)...

2.…with a track record of leveraging that power into adjacent markets

That’s a big (competition) problem!

13/

1. It has very significant (often discriminatory) market power in five markets (Search, YouTube, Android, Ad Tech, and Data)...

2.…with a track record of leveraging that power into adjacent markets

That’s a big (competition) problem!

13/

An important coda: Google’s dominance in (today: demog/location/interest) data worries us most. Because (1) data is a general-purpose input whose dominance can be leveraged in many markets & (2) it fosters discriminatory power (particularly concerning in health/finance). 14/

PART 2: Google-Fitbit in a time of Digital Platform introspection

Google-Fitbit arrived at a time of great introspection and antitrust and regulatory activity surrounding the activities of large digital platforms (DPs).

15/

Google-Fitbit arrived at a time of great introspection and antitrust and regulatory activity surrounding the activities of large digital platforms (DPs).

15/

2019 saw many reports on DPs by competition authorities and antitrust experts: the @ACCC ( https://www.accc.gov.au/focus-areas/inquiries-ongoing/digital-platforms-inquiry), the UK’s Furman Report ( https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/unlocking-digital-competition-report-of-the-digital-competition-expert-panel), the EC’s Expert Panel ( http://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/reports/kd0419345enn.pdf), and the @StiglerCenter Report ( https://www.chicagobooth.edu/research/stigler/news-and-media/committee-on-digital-platforms-final-report). 16/

In 2020, these have turned into tangible (US) antitrust and (EU) regulatory activity against Google and Facebook: State AGs re: Google ad tech ( https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/news/releases/ag-paxton-leads-multistate-coalition-lawsuit-against-google-anticompetitive-practices-and-deceptive#.X9pyvVvtRG4.twitter), DOJ re: Google search ( https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-sues-monopolist-google-violating-antitrust-laws), … 17/

FTC/State AGs re: Facebook monopolization ( https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2020/12/ftc-sues-facebook-illegal-monopolization), and proposals for regulating large DPs in the UK ( https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/digital-markets-taskforce) and EC ( https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/digital-markets-act-ensuring-fair-and-open-digital-markets_en). 18/

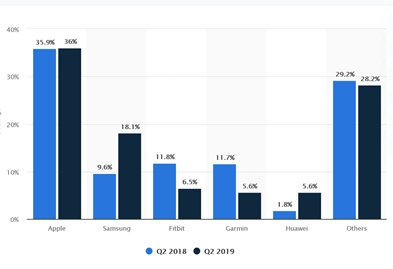

Into this comes Google-Fitbit (in 11/19). Based on traditional antitrust analysis, the deal raises no red flags: it looks like a merger of complements and Fitbit is a small player (2018-19 Q2 market shares via @IDC). 19/

Not so fast! Remember those reports? Some salient quotes:

From Furman (UK): “Historically there has been little scrutiny and no blocking of an acquisition by the major digital platforms… Our recommendations [are to] update merger policy [to be more] forward-looking…”

20/

From Furman (UK): “Historically there has been little scrutiny and no blocking of an acquisition by the major digital platforms… Our recommendations [are to] update merger policy [to be more] forward-looking…”

20/

From the ACCC: “Mergers framework should be updated ... [to account for the effects of] the acquisition of potential competitors and economies of scope created via control of data sets.”

(Even) from DG Comp’s *own expert panel*: 21/

(Even) from DG Comp’s *own expert panel*: 21/

PART 3: Google-Fitbit Theories of Harm (ToH)

There are two primary theories of consumer harm that Google’s acquisition of Fitbit would cause, each with multiple threads, and each alone sufficient cause (in our view) to block the merger.

22/

There are two primary theories of consumer harm that Google’s acquisition of Fitbit would cause, each with multiple threads, and each alone sufficient cause (in our view) to block the merger.

22/

We begin by saying what the theories of harm aren’t: they *aren’t* theories around online advertising. That horse has bolted: Google is dominant in online advertising and some form of antitrust/regulatory intervention beyond a Google-Fitbit remedy is needed.

23/

23/

The first, most concerning, theory of harm arises from Google combining Fitbit’s health and wellness data with their dominant non-health data to be used in life insurance & other markets where health data is likely to be valuable. This is not fanciful: https://www.adalovelaceinstitute.org/report/the-data-will-see-you-now/ 24/

Combining health and non-health data will allow Google to use non-health data to “customize” insurance offers. Does he gamble? Does she search for symptoms of life-threatening illnesses? It’s easy to see how such info could reduce the quality of insurance offers.

25/

25/

The EC says GDPR will protect people’s health data. But this is about Google’s use of their non-health data. Even if it did, predictions need only aggregate data; with privacy externalities (a growing lit on this), Google only needs to know the behavior of “people like me”.26/

Proponents say “efficiency gain!” Better prediction = better risk assessment = efficient markets. But this *could* be true only with competition. Because Google alone has dominant non-health data, they’ll extract the benefits from good risks and leave the bad.

27/

27/

Furthermore, with time Google will likely be able to predict consumers’ future likelihood of illness better than they can, leading to their being offered insurance (unknowingly) excluding these conditions or making them completely uninsurable. (hat tip Paul Heidhues)

28/

28/

Motivated by Google-Fitbit, these effects are analyzed in Chen, Choo, Cong, and Matsushima (2020), who conclude that when the complementarity of health and non-health data is large, merger causes long-run harms to competition and consumers.

https://ideas.repec.org/p/dpr/wpaper/1108.html 29/

https://ideas.repec.org/p/dpr/wpaper/1108.html 29/

Furthermore, nothing prevents Google from combining health & non-health data to predict behavior in markets beyond insurance: Is a potential employee likely to have mental or physical health issues? Can knowledge of someone’s health status or sexual preferences be monetized? 30/

More generally, consumers care about how their data is combined and used (even in the aggregate) and the combination of health and non-health data can also be interpreted as a quality-adjusted price increase of using Google’s *existing* services.

31/

31/

The second theory of harm focuses on the wearables markets and has two threads, both reflecting concerns about Google’s significant market power in a host of complementary markets (e.g. Android, Maps, Gmail/Calendar, Chrome, etc.).

32/

32/

If health and wellness data is valuable, Google has the ability and incentive to use these products to influence competition in the wearables market, e.g. by denying or degrading interoperability of Android/other products to rivals.

33/

33/

Furthermore, if wearables develop into an important access point for consumer attention (esp as voice recognition improves), Google will have a strong incentive to establish itself as the provider of the *operating system* for all (non-Apple) wearables.

34/

34/

Much as Google used Android to protect its dominant position in Search (the Google-Android case), it can use any/all of its strong complementary products to protect its dominant position in location and interest data coming from Android.

35/

35/

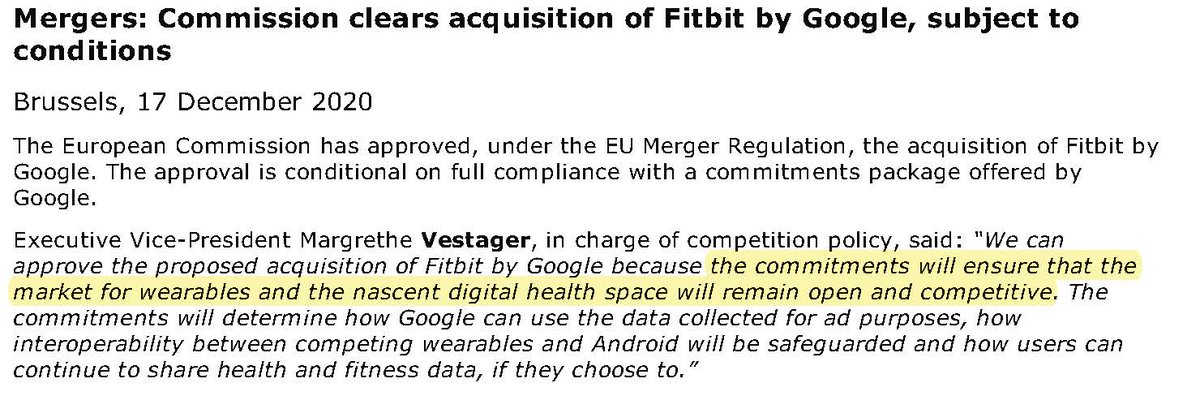

PART 4. The remedies are insufficient

In the clearance decision, @EC _Competition hailed three Google commitments which they feel will “make the market for wearables and the nascent digital health markets will remain open and competitive.” They are wrong. 36/

In the clearance decision, @EC _Competition hailed three Google commitments which they feel will “make the market for wearables and the nascent digital health markets will remain open and competitive.” They are wrong. 36/

The first commitment is about online advertising. As described above, online ads has already tipped to Google and, while it’s better than not having a further commitment not to use health data for online ads, it won’t solve the problems there.

37/

37/

The third commitment relates to Android interoperability (the 2nd theory of harm above). While Android interoperability is clearly important, it’s not enough: nothing prevents Google from leveraging market power from its other products into wearables markets.

38/

38/

The second commitment keeps open the API to Fitbit’s health and wellness data. This is a red herring. Access to Fitbit’s data isn’t a concern from the merger; access to Google’s non-health data is the concern from the merger.

39/

39/

Most concerning is there is no commitment related to the use of the combination of Google’s non-health data and Fitbit’s health data in insurance or any other market.

40/

40/

The decision concludes that Google would not obtain a competitive advantage in digital healthcare because “[the] sector is still nascent in Europe with many players active in this space.” 41/

This is faulty reasoning. There is direct harm to consumers coming from Google’s control over *non-health* data, an area with no other player (other than perhaps Facebook).

42/

42/

This merger should have been fought with every resource the EC had available to it. The theories of harm above are hard to prove, but the fight itself is important. They absolutely should have issued a SO and investigated them closely.

43/

43/

Maybe a prohibition would have been reversed in court & the EC was reluctant after their Hutch-O2 and Apple Tax losses. If so, so be it. Now was time for the EC to stand up & be counted & to establish the need for new merger rules to handle acquisitions by large platforms.

44/

44/

New merger rules *are* an important part of the UK’s proposed regulation of large platforms, but are missing from the EC’s DMA. We hear “lack of legal basis.” The UK CMA got there with their digital regime. It’s time to fill this hole in Europe – fix it, @EU_Competition!

45/

45/

We’re willing to bet that the Google-Fitbit will go down as a historically bad merger clearance, one that the EC will seek to undue with regulatory intervention down the road. It’s one bet we would be more than happy to lose.

END/

END/

Postscript 1: Many independent academics joined to refine and advocate these positions to the EC and other competition authorities. These included (esp) Paul Heidhues, @peitz_martin, @tomaso_duso, @MonikaSchnitzer, @mbourreau, Zhijun Chen, Chongwoo Choe, …

… @CGenakos, Thomas Rønde, Nico Schutz, @michellesovinsk, Giancarlo Spagnolo, @TomValletti, Otto Toivanen, and @Th_VRG. A VoxTalk w/ @Caffar3Cristina is at https://voxeu.org/vox-talks/should-google-be-allowed-acquire-fitbit and a writeup of some overlapping material is on @VoxEU ( https://voxeu.org/article/googlefitbit-will-monetise-health-data-and-harm-consumers).

Postscript 2: Neither I nor any of the aforementioned consulted for any party involved in this transaction. See the Authors’ note in the previous VoxEU link for disclosures for each of the authors.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![From the ACCC: “Mergers framework should be updated ... [to account for the effects of] the acquisition of potential competitors and economies of scope created via control of data sets.”(Even) from DG Comp’s *own expert panel*: 21/ From the ACCC: “Mergers framework should be updated ... [to account for the effects of] the acquisition of potential competitors and economies of scope created via control of data sets.”(Even) from DG Comp’s *own expert panel*: 21/](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ep1eL6pXYAE4Sr5.jpg)

![The decision concludes that Google would not obtain a competitive advantage in digital healthcare because “[the] sector is still nascent in Europe with many players active in this space.” 41/ The decision concludes that Google would not obtain a competitive advantage in digital healthcare because “[the] sector is still nascent in Europe with many players active in this space.” 41/](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Ep1fddkXUAIEpmV.jpg)