If you want a single, vivid, and frankly disgusting example to hold in mind to remember how much our lives have improved over the last ~150 years…

Consider *shit*.

Literally, excrement. How much previous generations had to think about it, be around it, even handle it:

Consider *shit*.

Literally, excrement. How much previous generations had to think about it, be around it, even handle it:

Before the automobile, horses flooded the streets, and cities were mired in their muck. According to Richard Rhodes, in NYC, horses dropped 4 million pounds of manure and 100 thousand gallons of urine on the streets every *day*. (!)

And Robert Gordon quotes this passage from *The Horse in the City*. “On New York’s Liberty Street there was a manure heap seven feet high.”

Shoveling shit was literally a full-time job. And one of the key uses of horses was to pull the wagons that carried away horse droppings.

Shoveling shit was literally a full-time job. And one of the key uses of horses was to pull the wagons that carried away horse droppings.

But excrement wasn't just something to be cleared away. Oh no, that would be a profligate waste! Shit was valuable. It was a *treasure*. It was *gold*.

It was fertilizer.

It was fertilizer.

For thousands of years, manure, mainly from livestock, was the primary way to renew the fertility of the soil after each harvest.

Agricultural systems were defined in large part by how much manure they could effectively use on arable land.

Agricultural systems were defined in large part by how much manure they could effectively use on arable land.

The transition from slash-and-burn to the two-field rotation of antiquity depended on livestock that would graze in pasture, then be penned in on fallow fields at night to fertilize it with their droppings.

The transition to the three-field rotation depended on the plow, which among other things allowed manure to be buried under the soil; and the wagon, which allowed more manure to be transported.

(All this is described in *A History of World Agriculture* by Mazoyer & Roudart)

(All this is described in *A History of World Agriculture* by Mazoyer & Roudart)

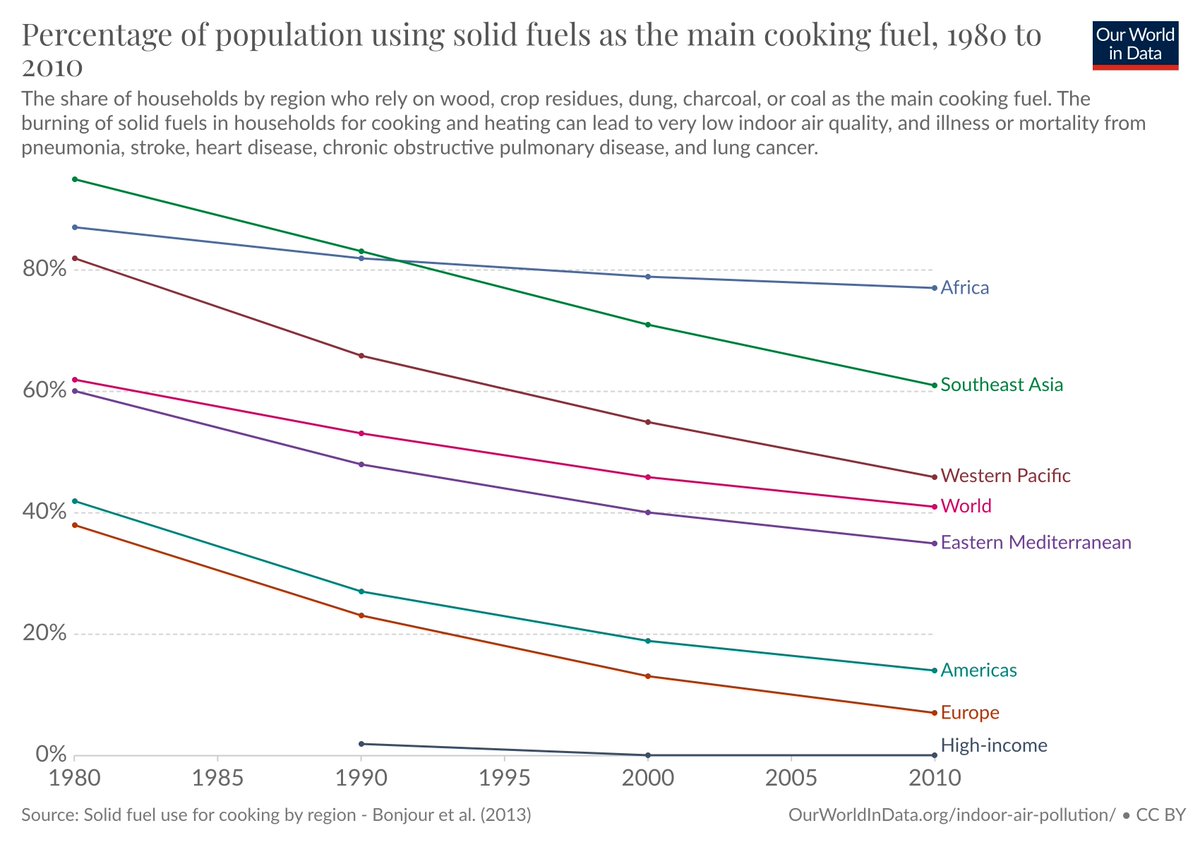

Dung was also used as fuel, in areas that didn't have much firewood, and even as a building material.

The poorest areas today still burn dung for fuel, contributing to indoor air pollution. https://ourworldindata.org/indoor-air-pollution

The poorest areas today still burn dung for fuel, contributing to indoor air pollution. https://ourworldindata.org/indoor-air-pollution

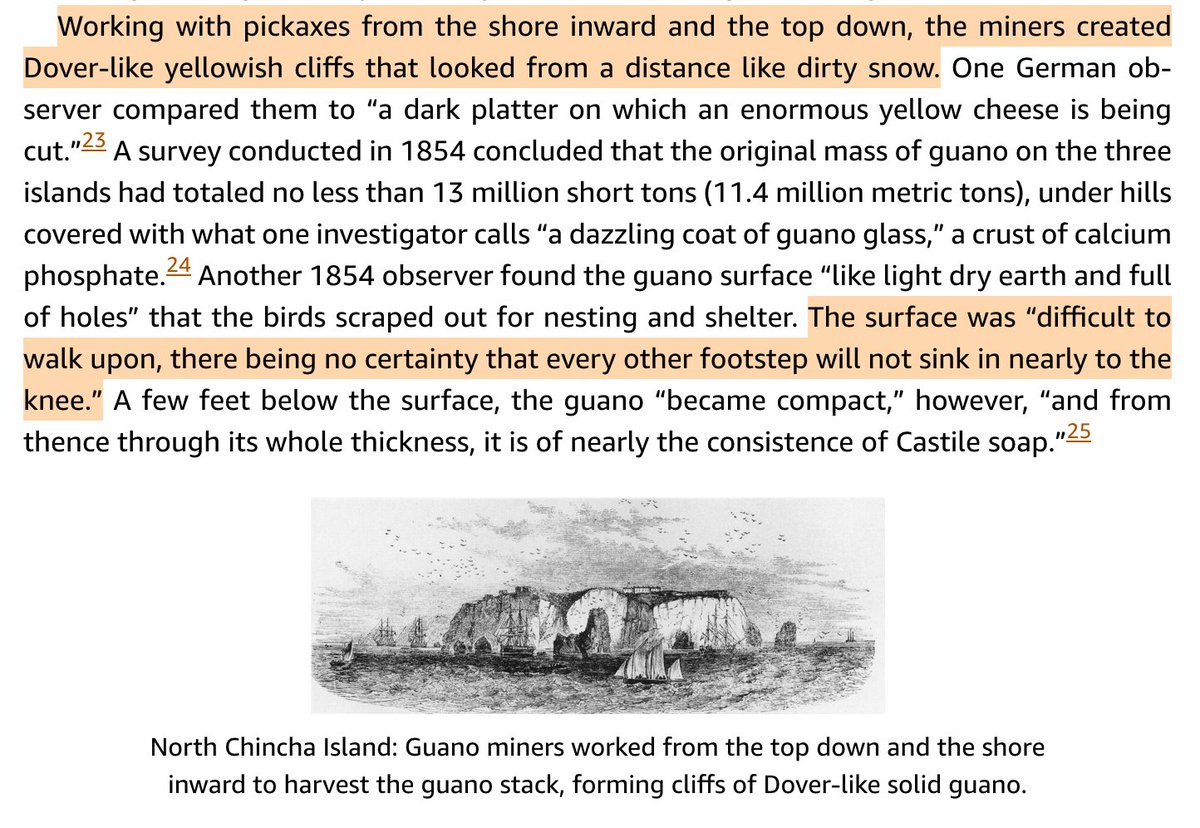

By the 1800s, the manure trade had gone global. The Chincha Islands, off the coast of Peru, where it rarely rained, had been accumulating seagull droppings for thousands of years. The accumulated guano, stories high, was mined like coal or lime and exported to Europe and the US.

The demand for fertilizer was so great that the islands quickly reached Peak Dung, and were exhausted in about 40 years.

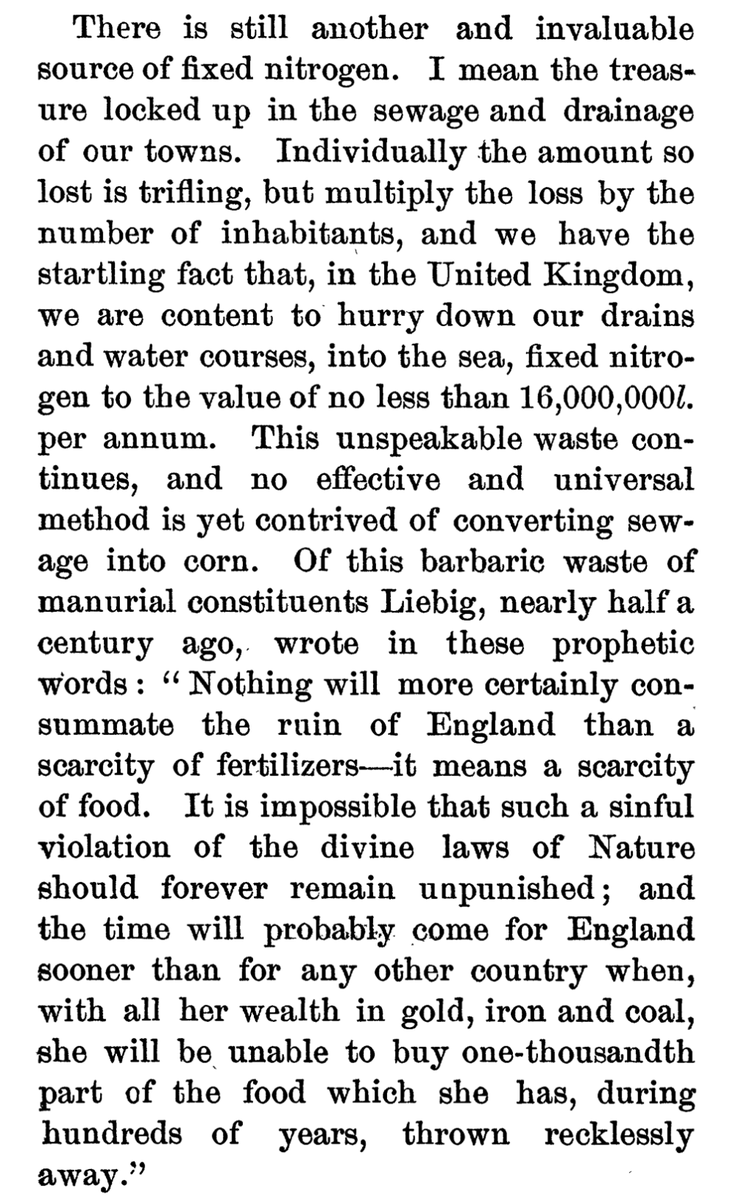

The need was so acutely felt that multiple commentators of the 1800s criticized *city sewers* because they did not capture human waste for reuse.

The need was so acutely felt that multiple commentators of the 1800s criticized *city sewers* because they did not capture human waste for reuse.

Sir William Crookes, in an 1898 speech, praised “the treasure locked up in the sewage and drainage of our towns” (!), lamented the “unspeakable waste” of “recklessly returning to the sea what we have taken from the land,” and pondered “converting sewage into corn.”

The 1902 Yearbook of the @USDA also refers to “the vast waste of nitrogenous material that is involved in modern sewage methods. Millions of dollars' worth of nitrogen which would naturally return to the soil… is every year carried off in various waterways….”

In *Les Miserables*, Hugo laments the same thing during his digression on the Paris sewers. “To employ the city to enrich the plain would be a sure success. If our gold is manure, on the other, our manure is gold.… A sewer is a mistake.”

https://www.compostingtoilet.com/?p=344

https://www.compostingtoilet.com/?p=344

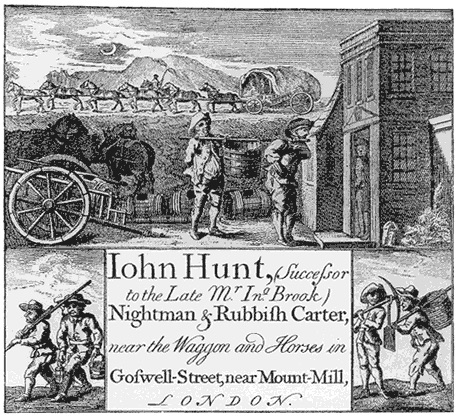

Indeed, not all the waste from the city was lost! Horse manure was carted back to the farms, as was some human waste, known as “night soil”. Collecting this stuff must have been a terrible job, but one John Hunt was proud enough to print this fancy calling card.

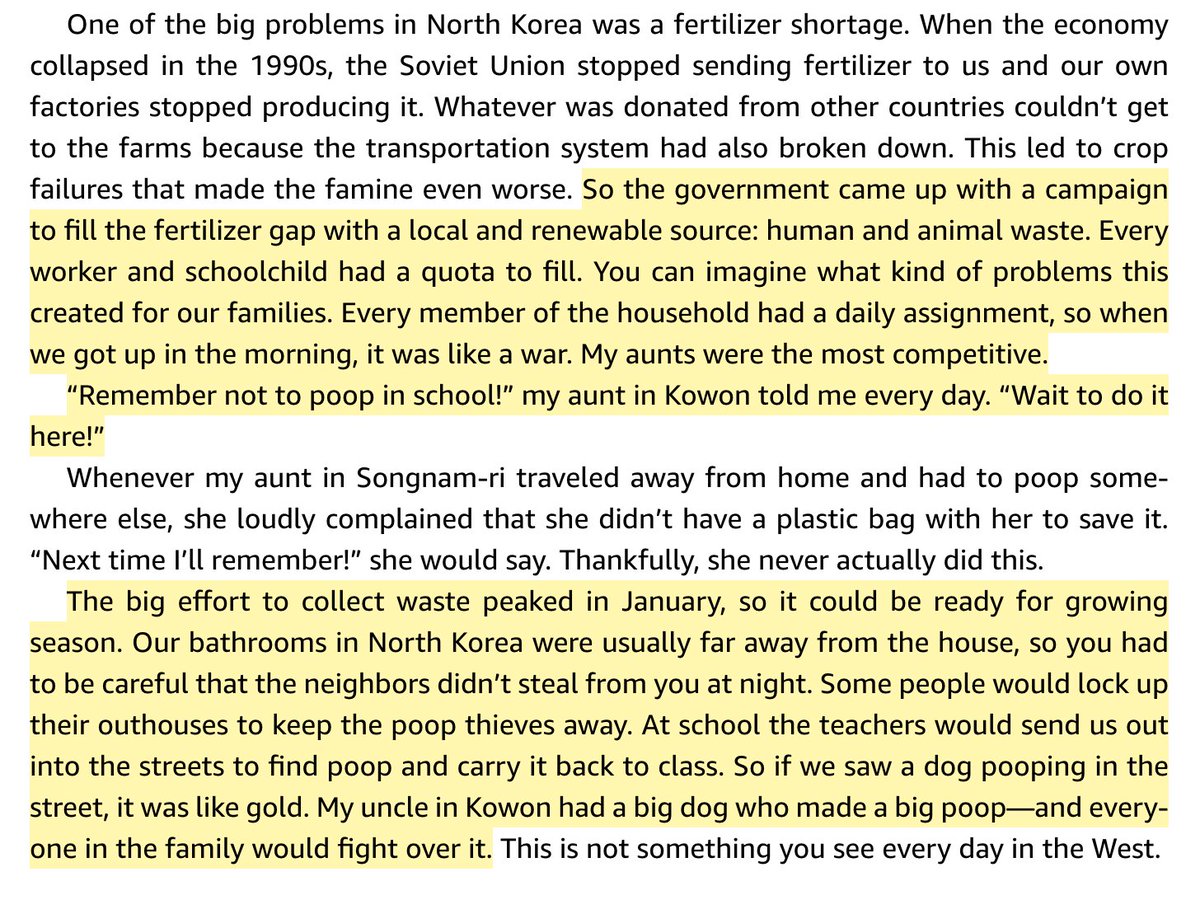

Night soil is still used in poor countries. In her memoir of life in North Korea, @YeonmiParkNK recalls her government “poop quota.”

Her aunt reminded her daily not to poop at school, but to save it for home. People would fight over poop, or steal it—some locked their outhouses.

Her aunt reminded her daily not to poop at school, but to save it for home. People would fight over poop, or steal it—some locked their outhouses.

In sum, excrement played a major role in life before the 20th century.

It was literally a crappy world.

It was literally a crappy world.

How did we get out of this shitty situation?

A few key inventions of the early 1900s: synthetic fertilizer, which released us from bondage to manure; and motorized transport—first electric streetcars, then automobiles—which ended (in Gordon's phrase) “the tyranny of the horse”.

A few key inventions of the early 1900s: synthetic fertilizer, which released us from bondage to manure; and motorized transport—first electric streetcars, then automobiles—which ended (in Gordon's phrase) “the tyranny of the horse”.

The adoption of both of these, I'm sure, was hastened by the new germ theory and the scientific realization that feces were a vector for disease.

Rhodes writes that as late as the 1850s, houseflies, which live on dung, were regarded as merry companions. In the late 1800s, public health messaging, seeking to change their image, portrayed flies as “germs with legs”.

Bottom line: The fact that excrement is hidden and flushed away from our daily lives—rarely seen, touched or smelled—is not the normal state of human existence. It is a great achievement of the modern world.

Turned this thread into a blog post: https://twitter.com/rootsofprogress/status/1341125428384165893

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter