Welcome back! I'm @khowaga, and we're discussing public health in 19th century Egypt. (1/24)

With the establishment of a national health corps, consisting of men and women--hakims and hakimas--who were trained in a formal curriculum designed by Clot himself, attention turned toward making the Egyptian nation healthy. (2/24)

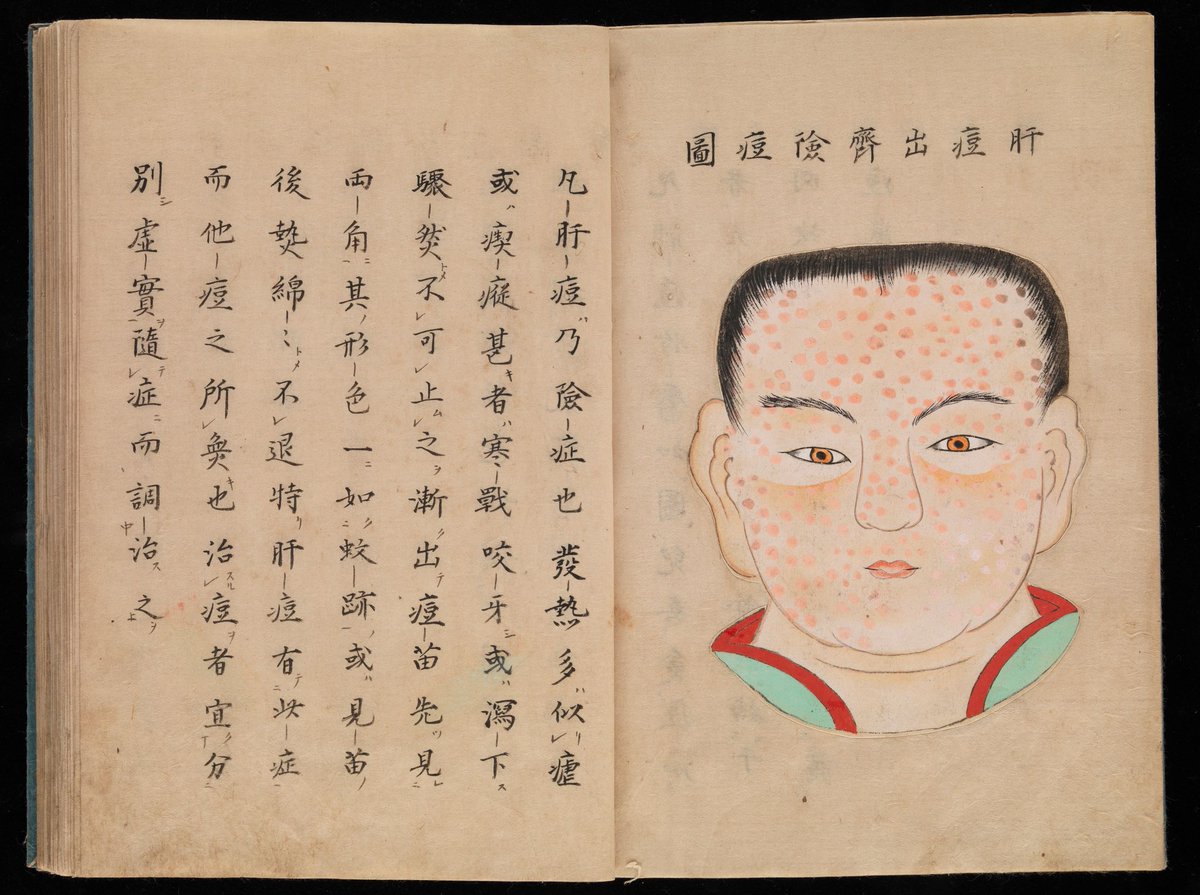

Before cholera first appeared in Egypt in 1831, the most feared diseases were plague and smallpox. Plague, which appeared perennially, only affected small numbers each year. Smallpox, however, was a routine scourge. (3/24)

The French had estimated that a third of infant mortality deaths were attributable to smallpox, and Clot estimated that the death toll from the disease was around 60,000 each year. (4/24)

Clot would later claim to have been the one to have introduced vaccination to Egypt in 1827, however, there were at least four documented vaccination campaigns prior to his arrival in the country. (5/24)

Variolation--the practice famously introduced to England by Lady Wortley Montague in 1721--had been performed in Egypt for centuries. (In class, I decided that Lady Montague sounded like Gillian Anderson as Margaret Thatcher in series 4 of The Crown.) (6/24)

Variolation is specific to smallpox (Latin: variola, hence the name), and it involves introducing fluid from the pustules of a person afflicted with smallpox into the body of a healthy individual. In China, scab material was ground up and snorted. (7/24)

The effect was similar to vaccination, in that the recipient would earn lifelong immunity, but with one very important difference: the person being inoculated would actually develop smallpox. Most often, the case was mild, but they were still contagious. (8/24)

Others could catch the disease--and at least a quarter of those who received variolation would develop a more serious case. People could, and did, die of smallpox as a result of the procedure. (9/24)

The procedure developed by Edward Jenner used cowpox lymph--cowpox being smallpox's zoonotic (animal-borne) cousin. It triggered the development of antibodies in humans, but without the risk of actually contracting the illness.

However, there was still resistance. (10/24)

However, there was still resistance. (10/24)

Although the idea of injection is regularized today, it is, at heart, a violent procedure. The skin is punctured, and foreign material injected into the body. There was also skepticism about the use of cow lymph. (11/24)

Hysterical stories went around England about children who started mooing and lactating after receiving the vaccine, and the enclosed cartoon shows infants being fed to an enormous cow (representing the use of anumal lymph), to come out the other end having grown horns. (12/24)

The question of whether the government had the right to mandate vaccination has also been around since the very beginning. (13/24)

Resistance in Egypt prevented the success of several early campaigns--Mehmet Ali's government had used forced labor for a number of projects, and teams of health officials were run out of towns by villagers convinced that children were being marked for service. (14/24)

In fact, the earliest systematic vaccination campaign coordinated by the Egyptian health service took place on Crete in 1832. (15/24)

An English physician noted approvingly that Mehmet Ali had specifically instructed that Muslim children should not be given priority over Christian children as smallpox would not discriminate between them. (16/24)

Slowly, over the course of the 1830s, small local campaigns would coincide with an outbreak and, as the vaccinated children did not contract smallpox, word spread and demand for the vaccine began to grow. (17/24)

Clot had hoped that hakims and hakimas would come to replace the traditional, untrained classes of medical practitioners--in particular the jerrahs (barber-surgeons) and dayas (midwives), whose "ignorance" he missed few opportunities to comment upon. (18/24)

However, with so few graduates--especially hakimas--the medical service began incorporating the jerrahs and dayas instead; giving them short courses on the administration of vaccines and other rudimentary tasks. (19/24)

In this way, I argue, over the 1830s and 1840s the authority and prestige of government-trained and medical professionals was established. (20/24)

The vaccination campaign brought them into the provinces as the expert voices who would impart modern medical knowledge to rural officials, establishing a clear hierarchy, and the Egyptian population became consumers of state-provided medical services. (21/24)

The official government journal reported that 61,000 children were immunized nationwide between 1837 and 1840. By 1850, 50,000 children a year were being vaccinated, and the number of cases of smallpox plummeted to just a couple of hundred. (22/24)

Writing in 1905, Fleming Sandwith, Director of the Egyptian Sanitary Service, was able to report that the “The horrors of the small pox as a general scourge” were now only “within the memory of old men” in Egypt. (23/24)

That's a pleasant note to end on for today. More tomorrow! (/fin)

~csr

~csr

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter