Welcome back! I'm @khowaga, and today I'm going to discuss public health in 19th century Egypt. I promise the thread will be more exciting than it sounds! (1/23)

#tweetistorian #histmed #twitterstorians #egypt #publichealth #history #everythinghasahistory #doihaveenoughhashtags

#tweetistorian #histmed #twitterstorians #egypt #publichealth #history #everythinghasahistory #doihaveenoughhashtags

It's important to understand that "public health" was a new concept in the early 19th century. Again, if we pay attention to European writers, one gets the sense that the rest of the world was centuries behind Europe in this regard, rather than a couple of decades at best. (2/23)

The idea really came out of post-revolutionary France, and it boiled down to this: strong nations need strong soldiers. Strong soldiers are healthy soldiers, raised by healthy parents (meaning, in particular, mothers, since they did much of the child rearing). (3/23)

In 1798, Napoleon's army invaded Egypt--the second (after Malta) in a planned series of conquests that was intended to challenge Britain's growing dominance in India. (4/23)

As is well known, the invasion was a military disaster. As the French marched inland to defeat the Mamluk armies at Imbāba, Admiral Nelson sank their fleet in Alexandria harbor; the French weren't occupiers of Egypt so much as trapped there. (5/23)

I haven't talked much about where I fit into the broader schools of Egyptian history (in general: awkwardly), but I am in the school that sees little lasting legacy of the French presence. (6/23)

The two major impacts of the French incursion were 1) rupture of the existing Mamluk-Ottoman administration, which allowed the Thracian-born Albanian general in the Ottoman army, Mehmet Ali--an outsider, to assume the governorship of Egypt in 1805; (7/23)

and 2) the production of the Description de l'Egypte, which provides a snapshot with which 19th century efforts to develop and industrialize can be measured. (8/23)

(link: Description de l'Egypte at World Digital Library: https://www.wdl.org/en/item/2410/#q=description+de+l%27egypte)

(link: Description de l'Egypte at World Digital Library: https://www.wdl.org/en/item/2410/#q=description+de+l%27egypte)

Urban sanitation in Cairo was probably similar to that of contemporary London and Paris--concern was directed at getting waste and refuse out of the house, but what happened to it after that was given little attention. (9/23)

The Khalig--a canal that ran through Cairo (it's now Port Said Street)--became infamous for its odor, which was so putrid that a commission was formed to investigate it in the 1830s (see: @khaledfahmy11, "An Olfactory Tale of Two Cities" for more on this.) (10/23)

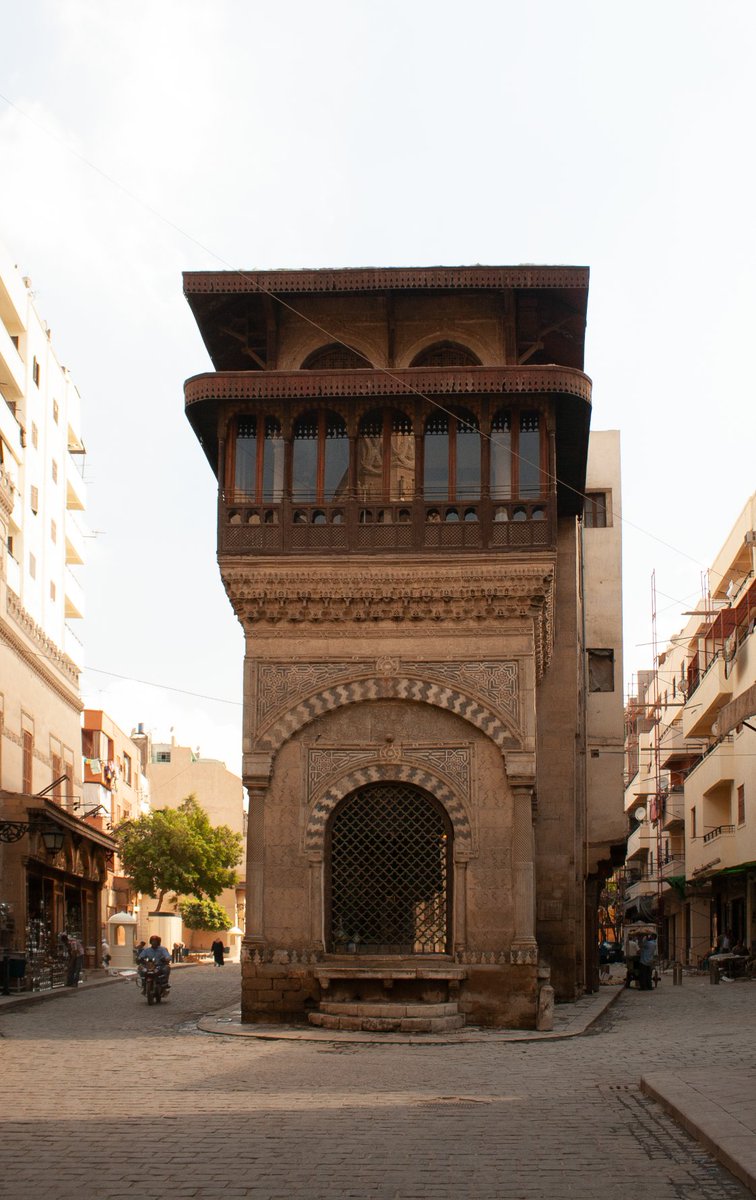

The French noted approvingly the number of public fountains and bathhouses, noting that personal cleanliness was important, particularly for wudūᶜ, the obligatory pre-prayer washing for Muslims. (11/23) (Photo: sabil-kuttāb of ᶜAbd al Rahmān Katkhūda, 1744).

The French scientists had hoped to find the storied public hospitals (māristāns) staffed by learned men, subsidized by the state for all, that were described in European travel accounts of Egypt from the Middle Ages. (12/23)

In this, they were disappointed. There was one public hospital in all of Cairo, the māristān al-Manṣūr, which was described as being in a “dilapidated” state. (picture: the māristān of Sultan Qalāwūn, 1284/5). (13/23)

The māristān al-Manṣūr served the same function as its equivalent institutions in Europe: hospitals were functionally poorhouses, charitable institutions obliged to take in the destitute, poor, and mentally ill whose families could not care for them. (14/23)

The idea of the hospital in the modern sense (and that described in the medieval accounts of Egypt), that of an institution staffed by professional doctors and scientists that served as a hub for medical treatment, training, and research--(15/23)

--had only begun to emerge in Europe at the end of the 18th century in Paris, Vienna, and London. In 1798 Egypt, as well as in Europe, the idea that the government bore any responsibility for ensuring the health of its citizens was new and revolutionary. (16/23)

To say that sanitary and medical practices in Egypt were roughly on par with those of Europe at this time is to say that neither were well developed. (17/23)

The French officers and scientists who recorded their observations, however were either uninclined or unable to recognize the similarities between the standards of medical care available to lower class Egyptians and those available to lower class Europeans. (18/23)

For example, as LaVerne Kuhnke observed, French scientists wrote damningly of the infant mortality rate in Cairo without recognizing that it was on par with, and mostly due to the same causes as, the infant mortality rate in poor neighborhoods of Paris... (19/23)

...and that these were not unique to Egypt, but rather indicators of urban poverty. (20/23)

As Kuhnke and Estes reported, about three-fourths of the drugs available in Cairo pharmacies were mentioned in several official drug lists in France as well as the Edinburgh New Dispensatory then standard throughout the English-speaking world. (21/23)

In short, at the time of the French departure in 1801, healthcare in Egypt may have been rudimentary and basic, but it was not significantly different from that available in Europe. (22/23)

What happened next is not a well known story, and that's a shame, because it's a good one. (/fin)

~csr

~csr

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter