Can America get to net zero emissions by 2050, as Biden has pledged? A big new study from @JesseJenkins and his Princeton colleagues goes into exhaustive detail on what it would take to get there. I wrote about it here and I'll note a few things below: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/15/climate/america-next-decade-climate.html /1

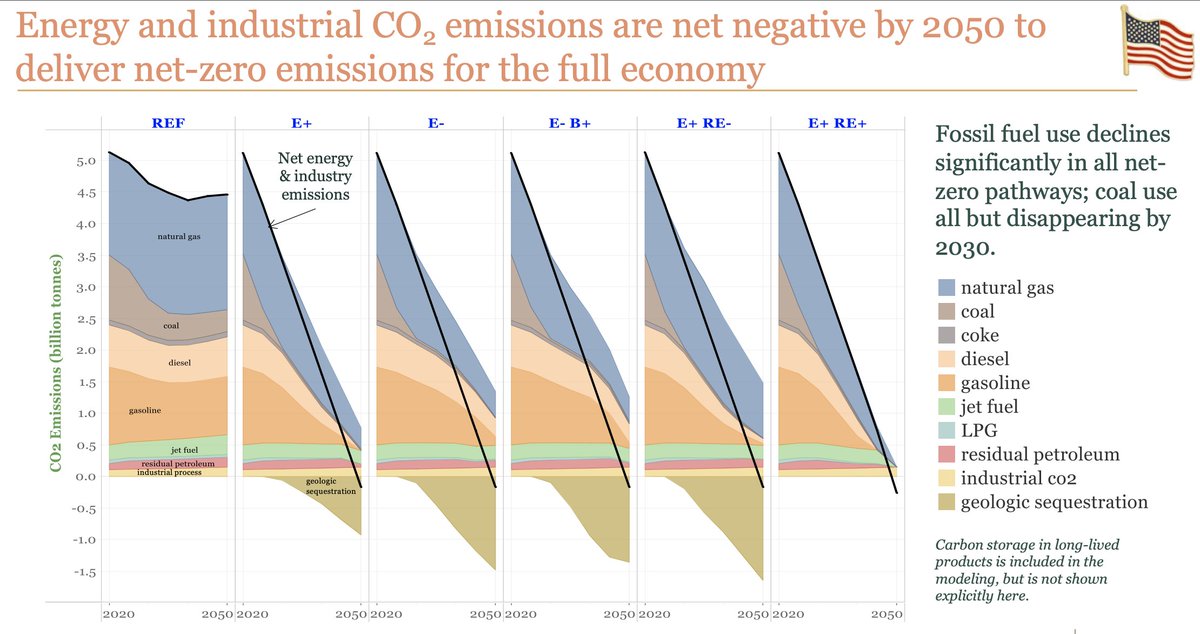

First, the researchers model five big plausible technological pathways for getting to net zero by 2050. There's a 100% renewable path (#5), a path where wind and solar struggles (#4), and a blended path (#1). All seem doable, but each has pros and cons. https://environmenthalfcentury.princeton.edu/sites/g/files/toruqf331/files/2020-12/Princeton_NZA_Interim_Report_15_Dec_2020_FINAL.pdf /2

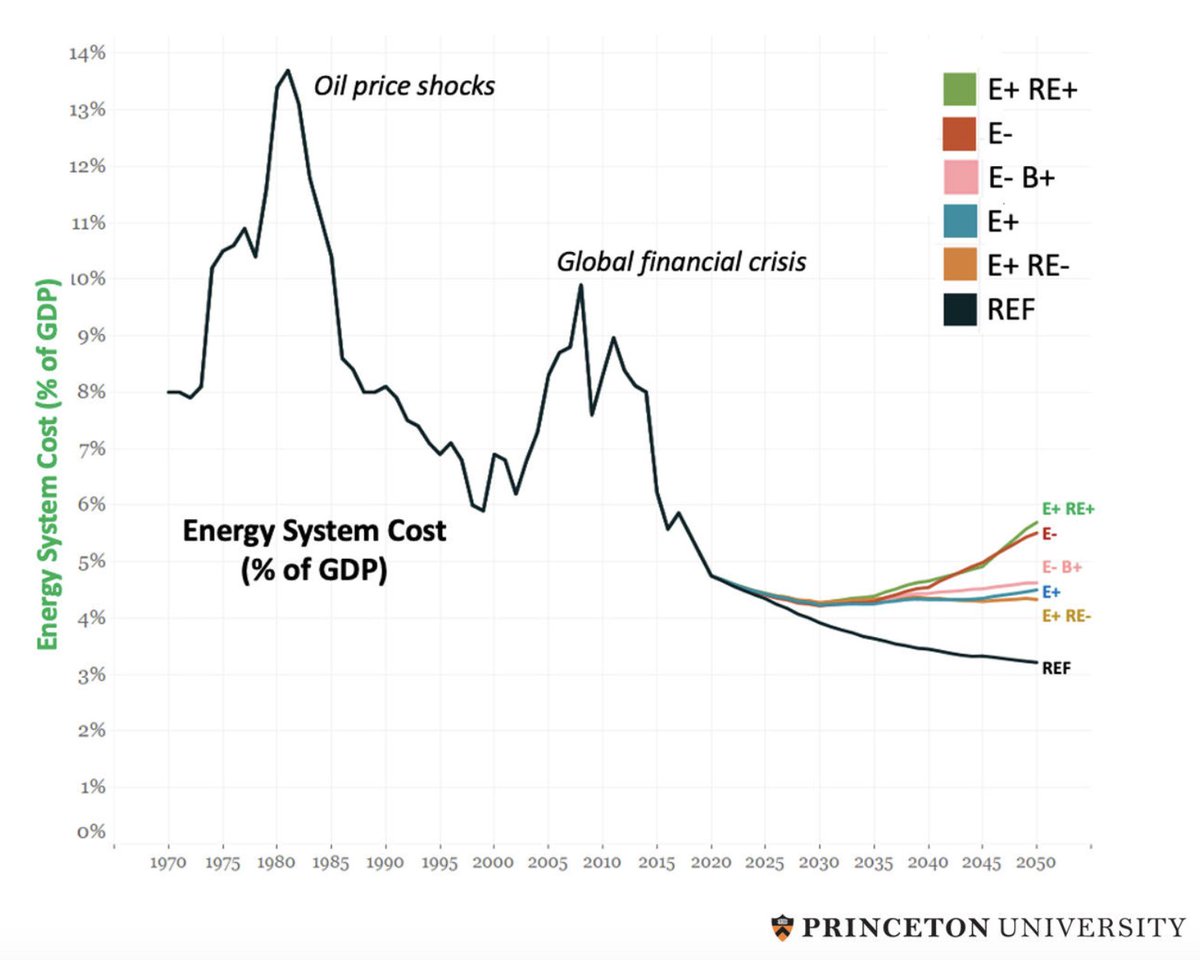

All of these modeled scenarios appear broadly affordable. In each, total energy costs as a share of GDP remain lower than in the 1990s/2000s (but higher than doing nothing). Also throw in major air-pollution benefits: 40,000 avoided premature deaths next decade alone. /3

The bigger challenges may lie elsewhere. How to mobilize all the extra upfront capital needed to shift the energy system ($2.5 trillion by 2030 alone)? What to do about displaced jobs? And where and how are we going to build all the sheer *stuff* we need for net zero? /4

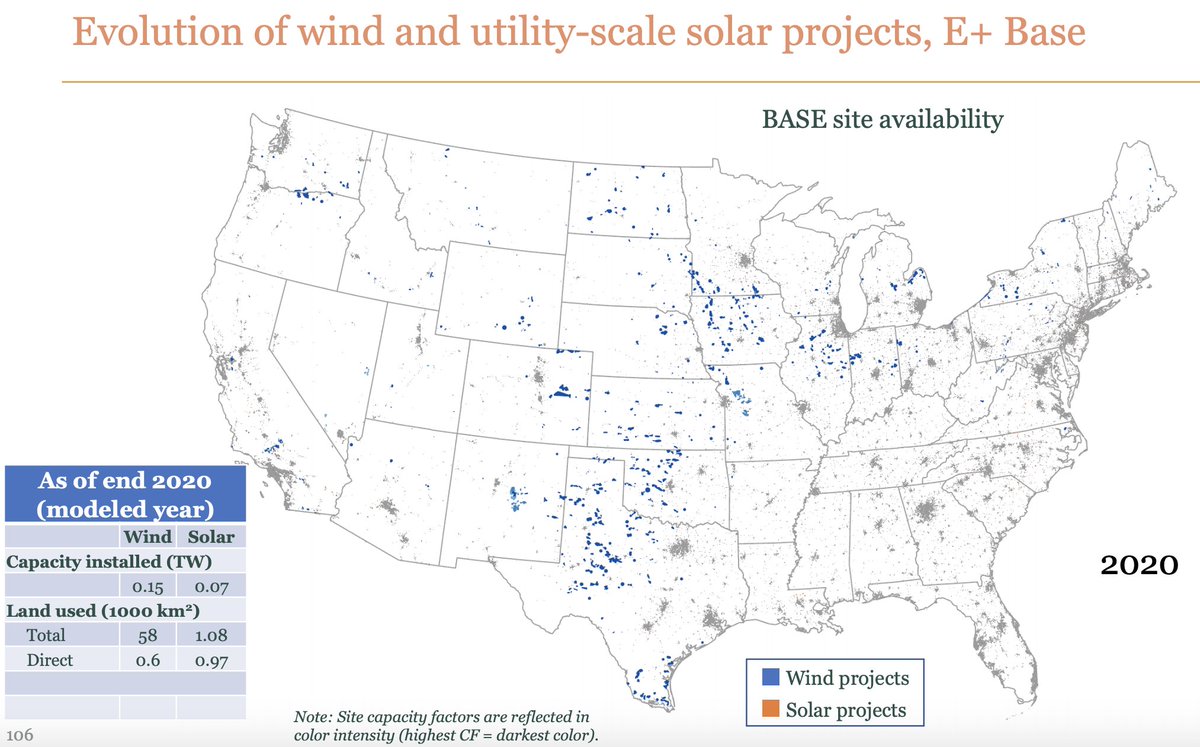

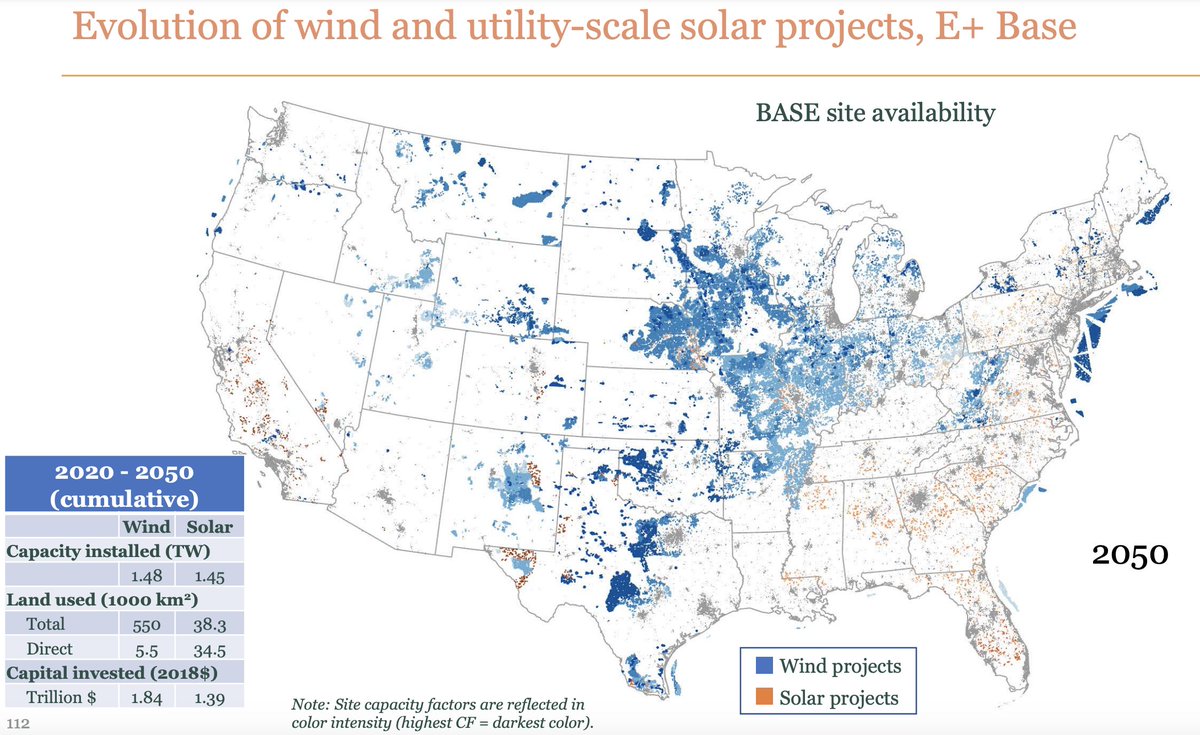

The study uses detailed mapping to figure out where all those new wind turbines, solar panels and transmission lines might plausibly be located. It is a *lot.* See 2020 vs 2050 below. While there's technically enough land, that many projects could mean more local opposition. /5

That's where some of the trade-offs come in. If we want to get to net zero *only* using renewables — no nuclear or fossil fuels allowed — that involves roughly twice as much land and somewhat higher costs. (Interestingly, we'd likely still need carbon capture.) /6

Conversely, if you don't think renewables can grow any faster than they have historically, say because of land use constraints, we'll likely need tons of new nuclear reactors or gas plants with carbon capture, technologies very much in their infancy and possibly expensive. /7

The researchers also look at a scenario where electrification struggles to take off — if, say, people are slow to ditch their regular cars or gas stoves/furnaces. In that case, then, we'd need a lot more carbon-neutral liquid fuels and biomass, which have their own drawbacks. /8

This modeling work doesn't tell us which path is "best." It doesn't even say the U.S. must follow one of these exact paths. But it does illustrate some of the tradeoffs involved in each. Don't like natural gas with CCS? Fine, but then we have to solve these problems, etc. /9

But here's one key takeaway from the study. No matter which path we ultimately choose, there's a pretty similar set of actions that likely needs to happen between now and 2030 in all scenarios. These are big, drastic changes. I describe some here: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/15/climate/america-next-decade-climate.html /10

(Also just realized I left a big item out. Under all scenarios, the researchers found, we likely need to keep as much of the existing nuclear fleet running for a decade or more, to keep CO2 down — regardless of whether we ultimately extend, retire or replace those reactors.) /11

In essence, the whole debate over 100% renewables vs other strategies can be set aside for a bit. The next decade is about making as much progress as possible with today's proven technology, while building up options for the 2030s/2040s with R&D and infrastructure. /12

One way to think about it: It's clear how to quickly slash emissions by 2030 — via renewables and electrification — and we'll need to go full speed ahead on that stuff. Past 2030, the answers get murkier, and we'll also have to spend next decade clarifying those answers. /13

That means R&D for a bunch of different technologies, but also building infrastructure for the future now. If we want to do industrial CCS (which looks vital), we'll likely need thousands of miles of pipelines and dozens of demo plants by 2030. Can't just sit around and wait. /14

One note: probably the toughest near-term action item in the study is expanding the national grid's capacity by 60% by 2030 (!). Given how hard it is to build transmission today, that looks like a huge hurdle. Some new research on policy options here: https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/research/report/building-new-grid-without-new-legislation-path-revitalizing-federal-transmission-authorities /15

I also dove into this recent report from @sdsnusa, which used similar modeling to the Princeton study and lays out dozens and dozens of policies that the feds, states, and cities could pursue for net zero — they have a similar basic game plan by 2030: https://www.unsdsn.org/Zero-Carbon-Action-Plan /16

Of course, just because the models say it's feasible and affordable to go net zero by 2050 doesn't mean that's how it'll work in the real world, as Susan Tierney says. But a roadmap can at least help identify some of the big challenges ahead... https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/15/climate/america-next-decade-climate.html /17

One thing I'll add about the Princeton study partially being funded by BP/ExxonMobil. I did think that was worth mentioning in my story. But also worth noting that their modeling results were *extremely* similar to those in the SDSN study, which had no fossil-fuel funding. /18

(The two studies used similar models—the biggest differences were assumptions about future oil/gas prices, which can sway CCS deployment.) Now, the models could still be wrong! But if you're curious why I didn't just dismiss the study because of Exxon/BP, that was one reason. /19

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter