The Chishtī Ṣābirī Sufi Shāh Muḥibbullāh Ilāhābādī is perhaps one of the most celebrated figures in Mughal intellectual history, acting as a confluence of the school of #IbnArabi #Avicennism and engagement with the court and #PersoIndica 1/

He is actually presented within the long and significant engagement with the school of #IbnArabi in North India and juxtaposed (at least in the much later reformist historiography) against the 'Naqshbandī' reaction of Shaykh Aḥmad Sirhindī (d. 1624) against monism 2/

He is sometimes co-opted into the polemics between the rigid 'Islamicity' of Aurangzeb and the 'liberal' tradition of Akbar and Dārā Shikoh - as one sees here https://www.jstor.org/stable/44141141?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents in which liberal is short for syncretic 2a/

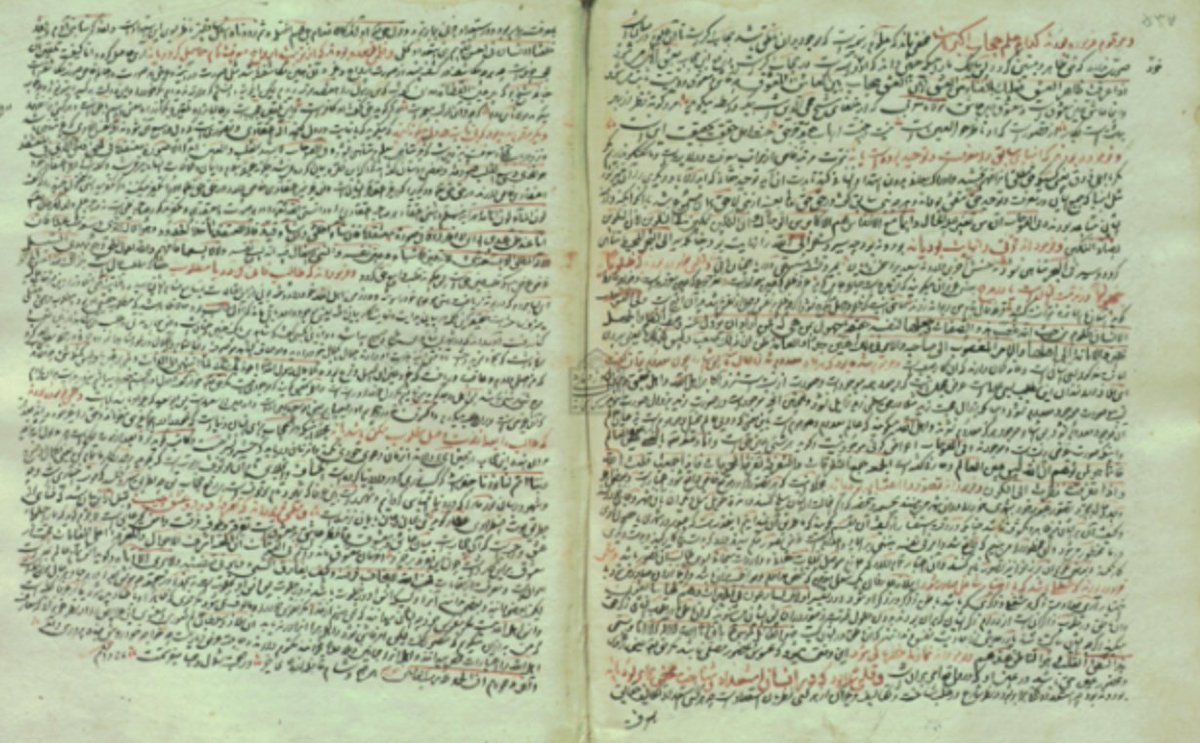

Or he is seen as a syncretic figure and one of the many 'gurus' consulted by the prince Dārā Shikoh (d. 1659) - here is a page of the letters they exchanged from the Malek Library and Museum in Tehran - especially when Dārā was governor of Allāhābād 3/

Dārā had the Shahi Masjid build for him as his khānaqah and the complex and later tomb built for him were also designed to support his family and followers 3a/

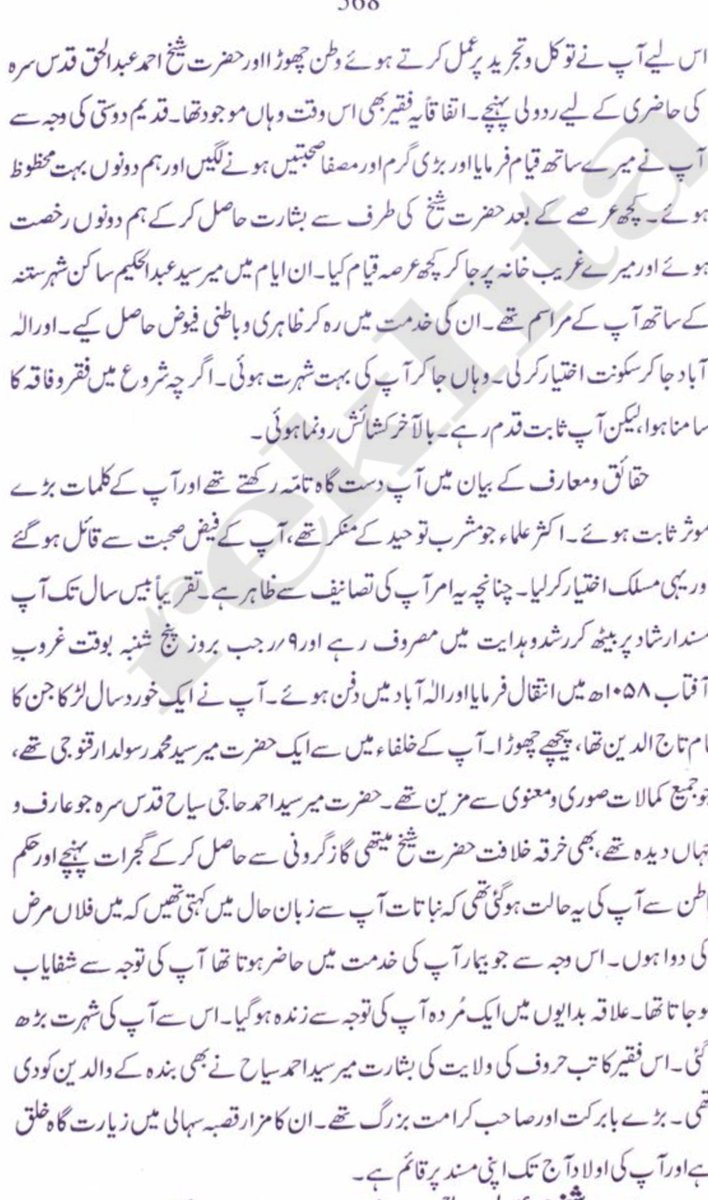

Still Muḥibbullāh deserves to be studied on his own terms - his entry in the famous Nuzhat al-khawāṭir biographical dictionary of Sayyid ʿAbd al-Ḥayy al-Ḥasanī (d. 1922) rector of Nadwa is one of the longest 4/

There are also studies of his Arabic text al-Taswiya and its Persian commentary, on the doctrine of existence, in Gregory Lipton's MA dissertation https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/xd07gt87z 6/

As well as Shankar Nair's recent book Translating Wisdom is probably the most extensive study https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520345683/translating-wisdom on which I draw here 7/

Muḥibbullāh was born in Ṣadarpūr in the district of Khayrābād in 1587, began his Sufi intiation into invocations and Yogic breath control there, and then studied philosophy in Lahore with ʿAbd al-Salām Lāhorī (d. 1627), whose lineage went back to the philosophers of Shiraz 8/

Later Lāhorī is one of the key links in the lineage from the Shiraz philosophers to the Farangī Maḥall philosophers in Lucknow in the 18th century 8a/

Muḥibbullāh's Anfās al-khawāṣṣ is an important account of his own life, his contacts and his practice presents as accounts inspired as commentaries on famous Sufi sayings or their 'breaths' 9/

Feeling the need for a spiritual master he sought out the Ṣābirī pīr Abū Saʿid Gangohī (d. 1639) and became his disciple and later successor 10/

In 1628, he settled in Allahabad where he died 20 years later in 1648 - this was his connection to Dārā although the prince didn't really spend time in the city where he was governor 11/

Ilāhābādī's students Mīr Muḥammad Qannawjī (d. 1690) and the well known Muḥsin Fānī (d. 1668) were figures at the court of Shāh Jahān and known to Dārā 12/

Qannawjī also became prince ʿĀlamgīr's tutor which might explain Aurangzeb (his regnal title) interest in Ilāhābādī's al-Taswiya later 13/

The controversy over al-Taswiya in the time of Aurangzeb led to the fatwā of some ʿulema in Allahabad condemning Ilāhābādī posthumously in 1664 as an unbeliever (for his support for monism) - although we should read some of these tazkira accounts carefully 14/

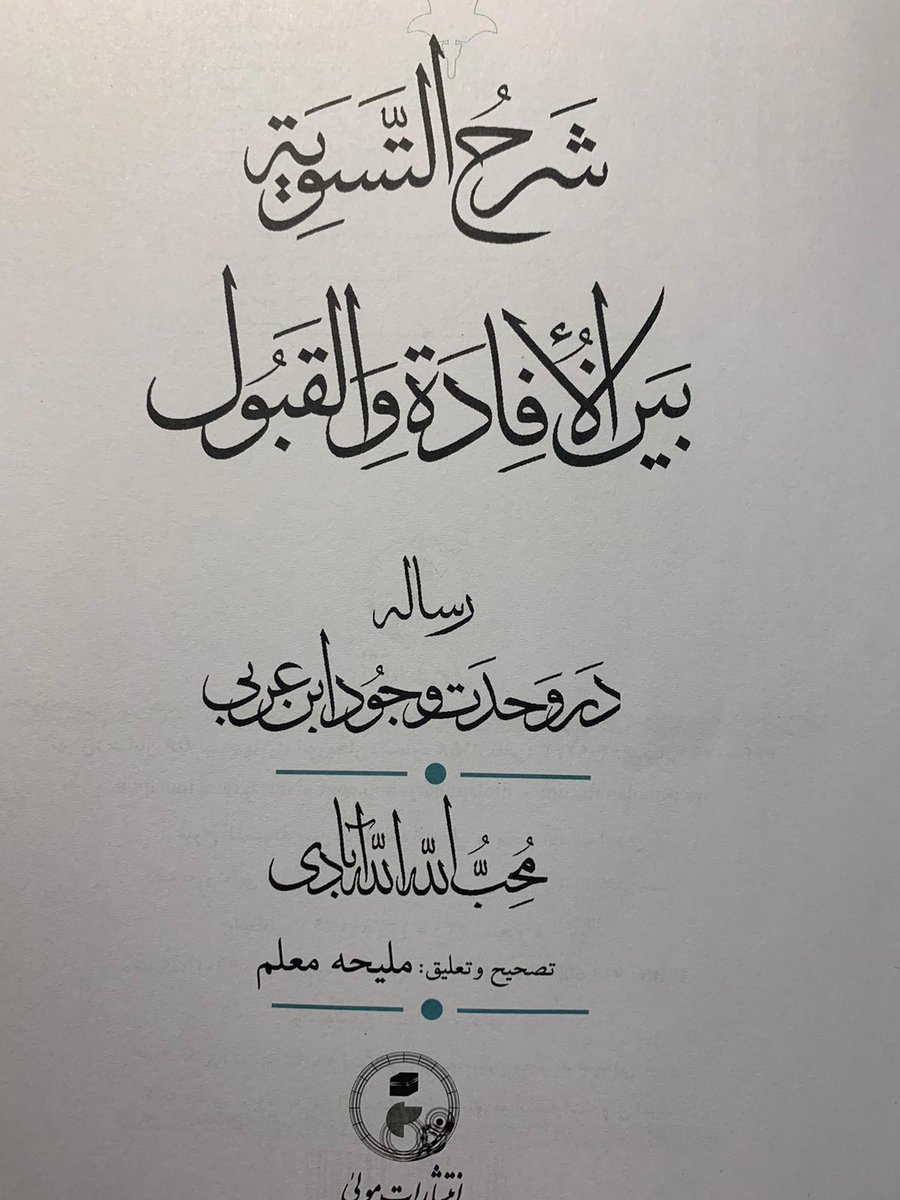

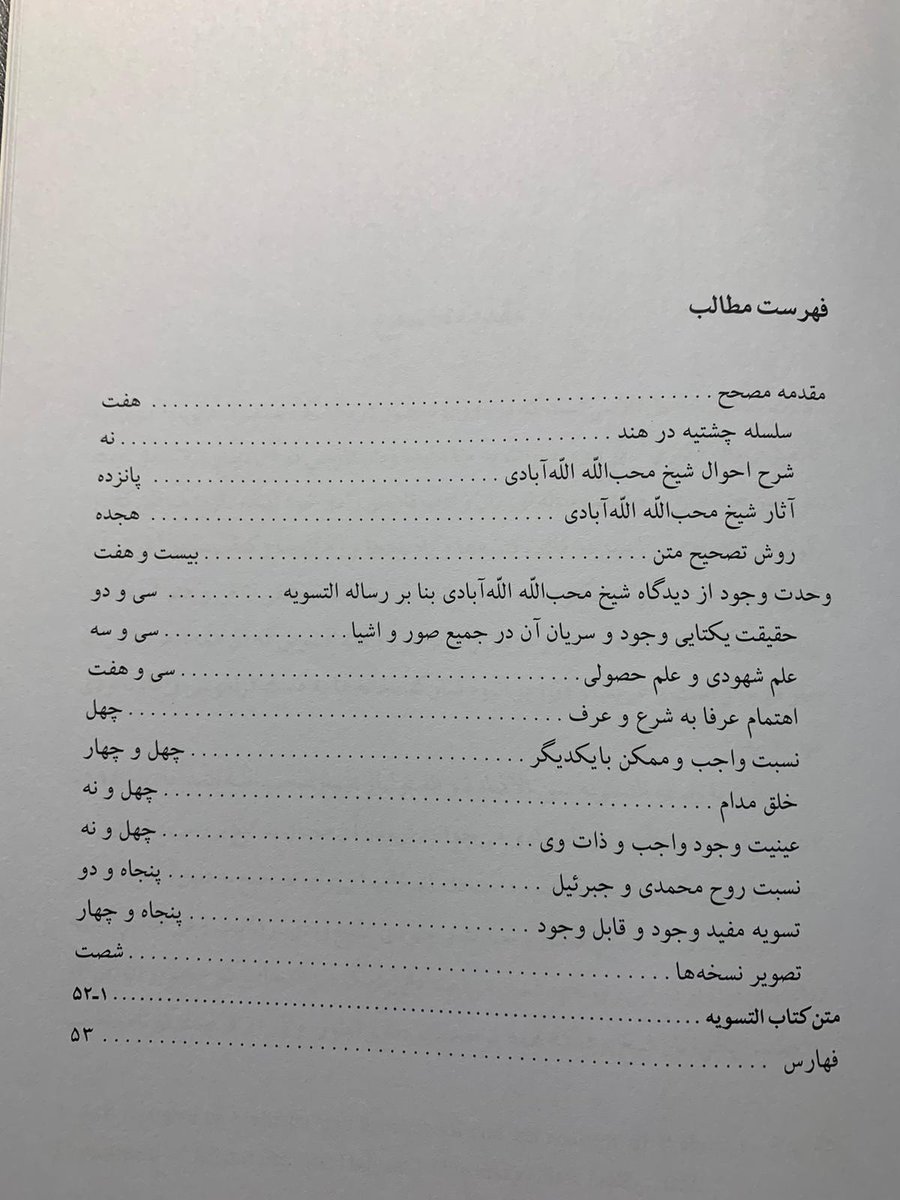

His best known works 1) his commentary on the Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam of #IbnArabi first in Arabic in a shorter form entitled Taḥliyat al-Fuṣūṣ and a more extensive Persian Sharḥ-e Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam in 1631 that was solicited by Dārā 2) al-Taswiya bayn al-ifāda waʾl-qubūl 15/

The Taswiya is an intervention into the debate on existence and into the school of #IbnArabi and #Avicennism equally critiquing the circle of Sirhindī and Maḥmūd Jawnpūrī (d. 1652) 15b/

Jawnpūrī later wrote Ḥirz al-īmān as a refutation of Taswiya and spawned a set of refutations and counter-refutations in the commentary tradition - the debate was also conducted in letters that Ilāhābādī wrote to Jawnpūrī 15c/

He also wrote Haft aḥkām in 1643, a translation and commentary on Futūḥāt of #IbnArabi Ch 177 on maʿrifat ('true knowledge', 'gnosis'), and in the same year ʿIbādāt-e khavāṣṣ on the arcana of worship glossing the relevant chapters of Futūḥāt 16/

Other works drawing on Futūḥāt included Manāẓir-e akhaṣṣ al-khavāṣṣ completed in 1640 on stations along the Sufi path, Ghāyat al-ghāyat on cosmogony - clearly a figure heavily in the school of #IbnArabi 17/

Further works reflected on the Sufi path: 1) Tarjumat al-Qurʾān in Arabic a short of exegesis and hermeneutics of the revelation 2) ʿAqāʾid al-khavāṣṣ a staunch defence of 27 subtle points on waḥdat al-wujūd 3) Risāla-ye sih suknī on spiritual practice of the 'pillars' 18/

He also has a short Risāla dar vujūd-e muṭlaq which was a central debate from at least the 14th century between philosophers, theologians and Sufis on monism and the true sense of 'absolute' or 'unconditioned' existence 19/

One way to gauge the controversy on Ilāhābādī is to take the account of the famous Chishtī Sufi of Fyzabad who was prominent at the Avadh court at the end of 18th C Shāh ʿAlī Akbar Ḥusaynī Mawdūdī 20/

He recounts his encounter with the works of Ilāhābādī in Allahabad in 1171/1758 which he enjoyed first but then realised the critiques were important; he mentions the following: 21/

1) the proposition that God as necessary existent encompassed specific contingents (or the panentheistic idea that things exist in God) 2) denial of any reality to anything beyond God 22/

3) Angels and jinn just as humans do not really exist 4) rejection of the reality of spiritual states and ecstasy 5) affirmation of the eternity of the cosmos 23/

In some ways these critiques are somewhat at odds with Mawdūdī's own works and defence of the school of #IbnArabi - and before even Awrangzeb did not ban or burn the Taswiya 24/

Further, Ilāhābādī's own positions in his Sharḥ-e Fuṣūṣ seem contrary to these allegations: for example, his realism on the existence of universals as ontologically prior to particulars and his invocation of the concept of mental existence 25/

Some final comments on his Sharḥ-e Fuṣūṣ: 1) while Jawnpūrī and others following Davānī insist that existence is a mere mental consideration, a quantifier that has no really outside of the mind, Ilāhābādī insists on the reality of existence that is graded 26/

While he does not invoke the idea of Mullā Ṣadrā on modulation, he does seem to follow Qayṣarī on the gradation in the level of manifestation of divine existence 27/

2) He also presents ideas on the nature of the all-encompassing mercy of God extended to all - diversity and plurality of religion and opinion are facts that have a divine mandate - one cannot limit God, the unlimited, to one's own conception of God 28/

Nair in particular makes mention of Ilāhābādī's religious pluralism and 'soteriology humility' in the Sharḥ 29/

The works of Ilāhābādī deserve more - a fuller understanding of the school of #IbnArabi and its debates from Khwāja Khwurd, Sirhindī, Ilāhābādī all the way to Mawdūdī and beyond - and one hopes that someone will take up Nair's excellent beginnings 30/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter