THREAD. It's a good day to talk about Mariem Hassan's music, and this track in particular, released in 2010 with an album bearing the same name. Mariem Hassan was among the most important and powerful Sahrawi artists and spokespeople of this century.

I'm not an expert on music or the Sahrawi struggle by any means, but I still think a close analysis of this song on its own teaches us a lot about colonialism as a world system, and the nature of anticolonial struggles and alliances. Here we go.

To start with some context, the song opens and is interspersed with the original audio of a 1976 speech by Spanish politician Felipe Gonzalez, delivered at a Sahrawi refugee camp. This man would later go on to become Spain's longest serving elected prime minister.

In the speech, Gonzalez makes a bunch of promises to the Sahrawi people, citing legal arguments for the end of the Moroccan occupation, as well as the will of the Sahrawi people. Mariem Hassan highlights the importance of this speech in the history of the struggle.

Hassan then criticises Gonzalez for backtracking on all his promises to the Sahrawi people. Following a clip in which he apologises for both "a bad colonisation and a bad decolonisation" and handing the Western Sahara to "reactionary governments", Hassan has this to say.

These lines demonstrate the pitfalls of relying on colonisers to support a struggle against another coloniser or occupying power. Colonial solidarity is strong, and it is a planetary system with its own constructed logics, just like (and intertwined with) capitalism.

Following a line of the speech where Gonzalez claims a kind of solidarity between the Spanish people and the Sahrawis, Hassan delivers this line. In my view, this is one of the most important lines of the song, because colonialism is its own economy.

The production of arms, like algorithms, is informed by the conditions of their use. A state that obtains weaponry to use in a system of colonisation will always be an attractive seller/buyer to those attempting the same. The core of colonising tactics are not all that diverse.

This is the point I keep repeating ad nauseum when discussing colonisation in Palestine and Kashmir, for example, and when highlighting the good relations between colonisers and autocrats or authoritarian regimes.

A line that should be forwarded to all of those who continue to believe that games of realpolitik or development economics will ever bring about liberation (or even relief) to occupied people anywhere in the world. Alliances with colonisers always start and end with dishonesty.

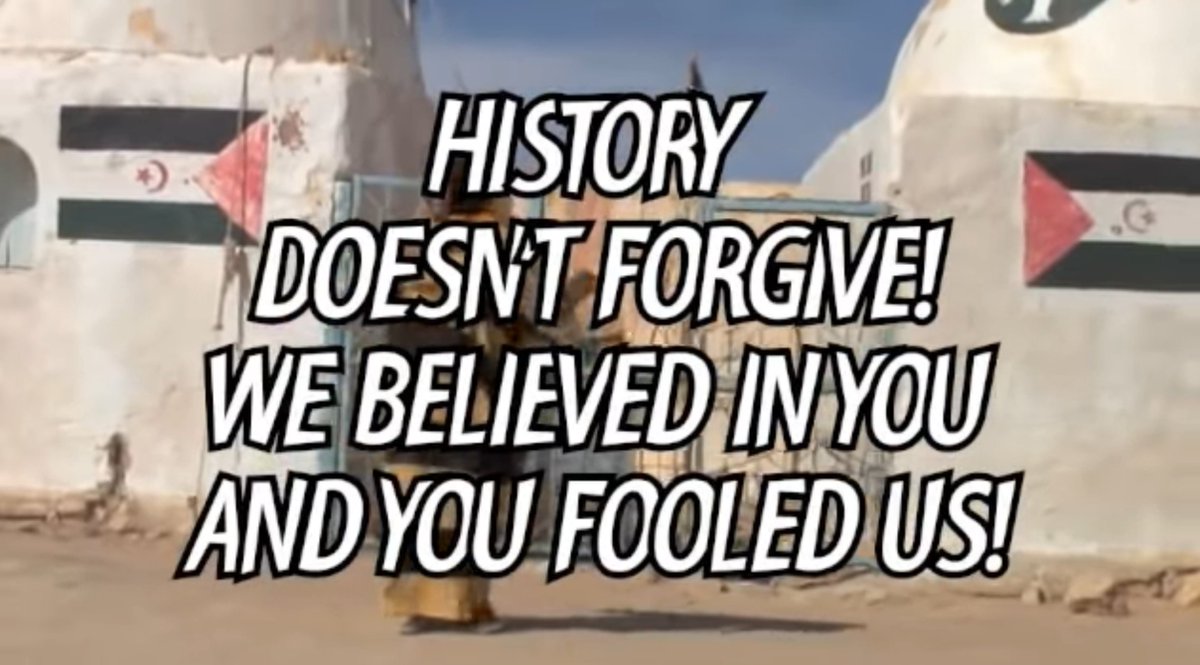

"We believed in you and you fooled us!" is a line that any indigenous person who sought an alliance or treaty with a coloniser can probably relate to since the 15th century. There is literally almost half a millennium's worth of evidence to demonstrate why this is so perilous.

The song ends on this note, which can be interpreted in at least a couple of ways (and I will leave this to the reader to figure out for themselves, for both of the ways I can think of are equally powerful).

The main lesson I think all colonised people should take from this song, which I think should be studied as an anticolonial text in its own right, is that colonisers will never be a part of our liberation, even if they are not OUR colonisers, per se.

I won't name names (because reasons), but those who have followed me long enough will know who I am referring to, and the Spanish/Gonzalez betrayal of the Sahrawi people is one of the best examples of this. I see echoes of this historical moment in the Obama administration too.

Of course, Trump never made Gonzalez-esque moves to try to appear as a liberator, but the incoming president has, and so Mariem Hassan warns us to be cautious and to not forget this duplicity when it inevitable happens (if it has not happened already).

Colonialism is a planetary system, meaning that the relations colonising powers develop with humans, resources, and each other are essential to how the world currently works. They will not compromise this for a colonised people.

Therefore, the struggle against colonisation in the Western Sahara, in Palestine, in Kashmir, or anywhere else the in the world is a struggle against how the world itself operates. It is a struggle against global and planetary systems. It is not discrete nor isolated.

The lives of the present are built on top of the dead bodies of colonised peoples, and so although over 500 years have passed, 2020 is still 1492, it is still 1620, it is still 1830, 1884, 1917, 1947 and 1975. Each of these dates is significant, even though we still live in them.

To conclude, if anybody wants to listen to the track in full, this is the link from which I took the screenshots in this thread.

And finally, a disclaimer: No specific events taking place in the world prompted me to write this thread. #IYKYK.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter