Does the pressure to publish in academia contribute to bad science? Some evidence suggests the answer is yes. A short thread on some recent research (I wrote more here). https://mattsclancy.substack.com/p/how-bad-is-publish-or-perish-for

First up, why would publication pressure lead to trouble? Isn't it good to hold academics accountable in some way? A famous 2016 paper by @psmaldino and @rlmcelreath used a computer simulation to provide one possible explanation. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.160384

In their simulation, labs evolve over time, subject to selection pressures. Labs that publish more "reproduce" more, and thereby disseminate their research approach more widely. But the paper also assumes novel hypotheses with positive results are easier to publish.

In that setting, labs who...

1. Don't do replication

2. Use methods most likely to lead to false positives

3. Exert low "effort" per project (so they do more total projects)

...reproduce the most and crowd out the rest.

Result: a literature full of false positives.

1. Don't do replication

2. Use methods most likely to lead to false positives

3. Exert low "effort" per project (so they do more total projects)

...reproduce the most and crowd out the rest.

Result: a literature full of false positives.

A key implication is that incentives and selection pressures drive the outcome. Better training and moral exhortation won't cut it. People have been raising alarms about methods in social science for decades, but, for example, the avg power in the lit is mostly unchanged.

Turning to data, two other recent papers look at the conduct of research by groups operating under different incentives, finding some evidence that yep, changing incentives changes outcomes.

First, @MBikard has a neat paper looking at perceptions of the "quality" of scientific research done by academia (where there are strong incentives to publish) and industry (not so strong). Which kind of paper is more likely to be cited in a patent? https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/full/10.1287/orsc.2018.1206

The trouble is, academia and industry probably work on different topics, so that's going to affect who gets cited, regardless of perceived quality. But what if you could find some cases where academia and industry worked on the same thing?

Bikard locates 39 cases where academic and industry researchers independently discovered the same thing (so-called "multiples"). Patents building on the discovery were 23% less likely to cite the academic paper than the industry one describing the same discovery.

That could mean a lot of different things. But Bikard also interviews a lot of people in academia and industry, and finds the following kind of thing is a not uncommon sentiment:

Another paper, by @RyanReedHill and @carolyn_sms, uses a remarkable dataset in structural biology to show the negative impact of publication pressure.

Structural biology is neat because there are standardized ways to assess the quality of protein models. https://economics.mit.edu/files/20679

Structural biology is neat because there are standardized ways to assess the quality of protein models. https://economics.mit.edu/files/20679

On top of that, scientists report both when they receive x-ray scattering data on proteins and when they finish their protein model. That lets Hill and Stein see how long researchers spend analyzing their data & how many people are working on the same (or very similar) proteins.

Key findings:

- Academic scientists spend less time analyzing data when there are more people working on the same protein (presumably, in order not to be scooped)

- This is associated with measurably lower quality protein models

- Academic scientists spend less time analyzing data when there are more people working on the same protein (presumably, in order not to be scooped)

- This is associated with measurably lower quality protein models

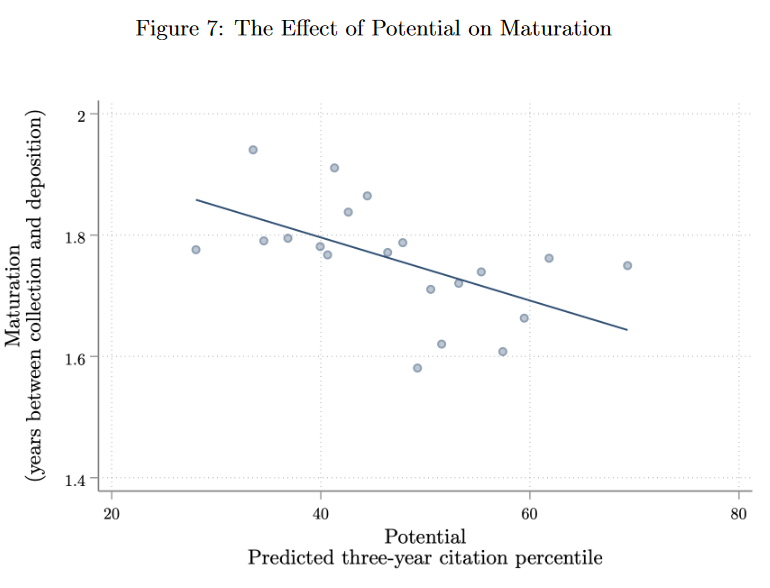

Worse; Hill and Stein estimate the "potential" of a protein (in terms of how many cites a paper about a finished model will get) and find the ones with the most potential attract the most researchers... which leads to shorter analysis and lower quality models!

But what about incentives? It turns out there is another group of federally funded scientists who plausibly face much weaker publication pressure. This is the group in red below. This group actually spends more time on proteins with more potential. Which is what we want!

My takeaway: if we want to improve science, we have at least some evidence that changing the incentives changes the results.

That said, on net science produces amazing stuff regularly. It's definitely doing something right. So change yes; but move carefully.

That said, on net science produces amazing stuff regularly. It's definitely doing something right. So change yes; but move carefully.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter