Today is the 70th anniversary of the European Convention on Human Rights. Much to celebrate. But how is it faring? Officially: very well indeed. But in reality? Not well at all … a longish thread.

In 2004 a review led by British judge Lord Woolf, concluded: “Without fundamental reform, the future for the Court is bleak.” Its backlog stood at 60,000 applications. By 2010, it was 150,000 . It was drowning. Not least because its judgments were increasingly being ignored.

Cue a decade long reform process that ended last year. The conclusion? According to Secretary General Jagland: “Because of the reforms we undertook … the Convention has put down deeper roots … and the procedures of the Court have been streamlined and become more efficient.”

A review concluded: “The reform process, backed by the effects of protocol 14, was crucial for the system & has led to significant advances which also bode well for the system’s capacity to meet new challenges. The necessity of a new major revision of the system is not apparent.”

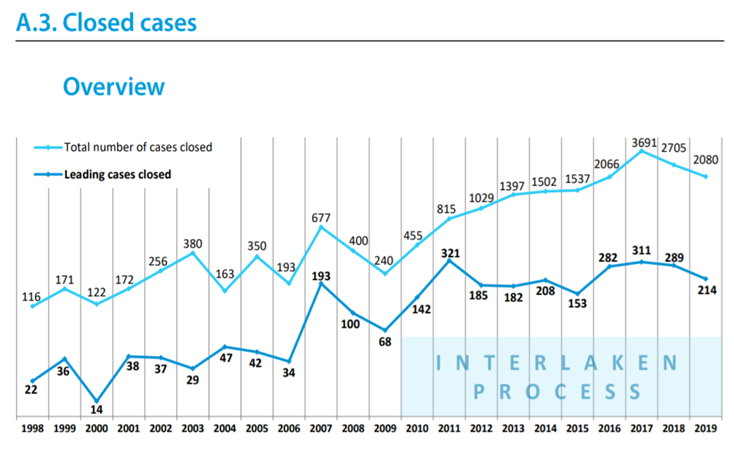

So all is well then. Except it isn’t. The backlog still stands at 60,000 cases and has done for years. The number of pending admissible cases is higher today than in 2010. Cases routinely wait 5 years for a judgment.

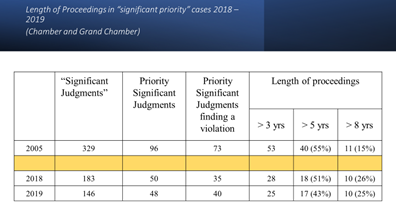

The graph below shows the average length of proceedings for the Court's most prioritised cases ... not great.

Official statistics suggest that the implementation of judgments has improved. But this is overwhelmingly result of rule changes not greater compliance.

Non-compliance is systematic in a number of countries. By the end of 2019 Russia had “closed” just 69 of the 291 “leading” cases (those highlighting a new issue) since its accession. Only 30 of these involved any kind of structural or policy change.

None of these related the to freedom of expression, assembly, politically motivated prosecutions, or Chechnya.

Azerbaijan is even worse. None of its 38 leading cases have ever been closed as a result of a policy change. Azerbaijan is a country that locks up journalists, political opponents activists.

Indeed, the conclusion that court is working is deeply at odds with the obvious: that the respect for human rights has clearly worsened over the last decade in these countries – and elsewhere, not least Turkey.

Look at this another way: what has the impact of the Court been on the big rights stories of the last decade? The authoritarian turns in Azerbaijan, Russia and Turkey? Not stopped them.

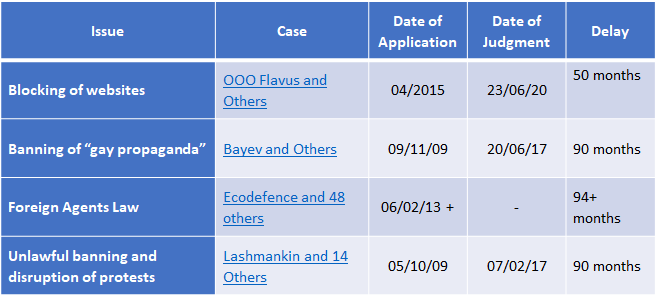

E.g: In the year after Putin’s return to the Presidency in 2012, Russia adopted 4 laws that clearly violated the Convention: on the blocking of websites, the banning of “gay propaganda”, the foreign agents law, and tighter restrictions on assemblies. These are all still in place.

The table below lists the cases covering these laws. (some were filed before their adoption as they raised similar issues). A ruling on the foriegn agents law is still pending

over 7 years later.

over 7 years later.

Turkey’s post-coup crackdown? 1000's still arbitrarily detained, not least the well known activist Osman Kavala, despite an ECHR ruling. My former colleague at Amnesty Turkey still has an absurd conviction for terrorism hanging over him. He has been waiting 3 years for a ruling.

Azerbaijan’s assault on civil society and opposition leaders? Those arrested on trumped up charges were eventually released: but most have left the country. The NGO scene has been obliterated. There is no political opposition any more.

The migration crisis? Judgments on key policy issues are still pending – Italy’s cooperation with the Libyan coastguard, returns to Turkey under the deal struck in 2016, the lamentable conditions on the Greek islands.

The capture of the Polish judiciary by the PiS government? Judgments still pending and will be for years yet. Conflict related violations in Georgia and Ukraine? No rulings.

In short, the Court is slow, irrelevant and ignorable. By the time its rulings come the harm has been done: government objectives have been achieved - individual remedies can be offered. They matter not by then.

This is not, on any meaningful measure, a system that is working. The Court still has a crisis of capacity and it has a growing crisis of compliance. Why is noone talking about this?

Offending states have no interest. The rest need the story of a functioning convention system to justify the retention of serially offending member states within the Council of Europe. Rights activists fear feeding the Court’s detractors and further reforms that might weaken it.

But the problems are glaring. The Convention system is decaying and it won’t be saved by silence or fictions.

Two things need to change. Firstly, the attitude to serial non-compliance. The departure of the serially offending must be contemplatable for the system’s integrity to be retained. Secondly the Court itself needs reform.

The Court cannot function as a court of last instance for 830 million people. The right of individual petition is the bed-rock of the Convention system – it must be retained - but it is killing the Court. Judgments need to be issued within 18 months not 50.

So here’s an idea: split the Court in two. A Court for new and serious cases. The ones that matter. It selects these – around 500 a year – and delivers judgments within a year. For all the rest, there is a Commission, that offers individual remedies as quickly as possible.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter