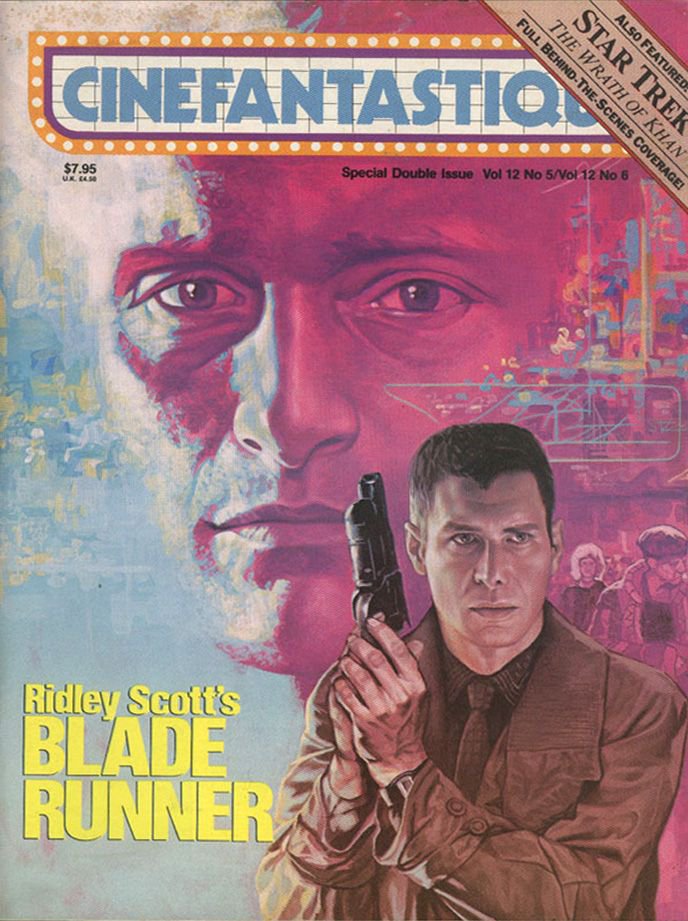

It's always a good day when Blade Runner is trending on Twitter, so let's look back at this classic 1982 movie and see how it compares to the book.

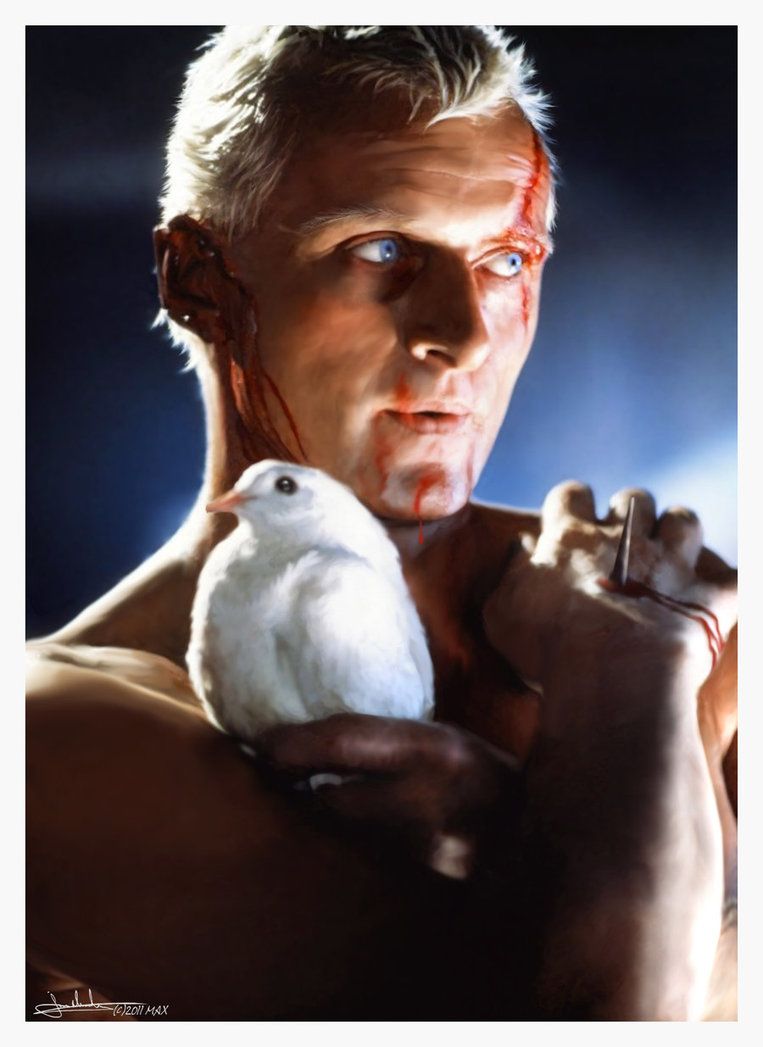

"It's not an easy thing to meet your maker..." #mondaythoughts

"It's not an easy thing to meet your maker..." #mondaythoughts

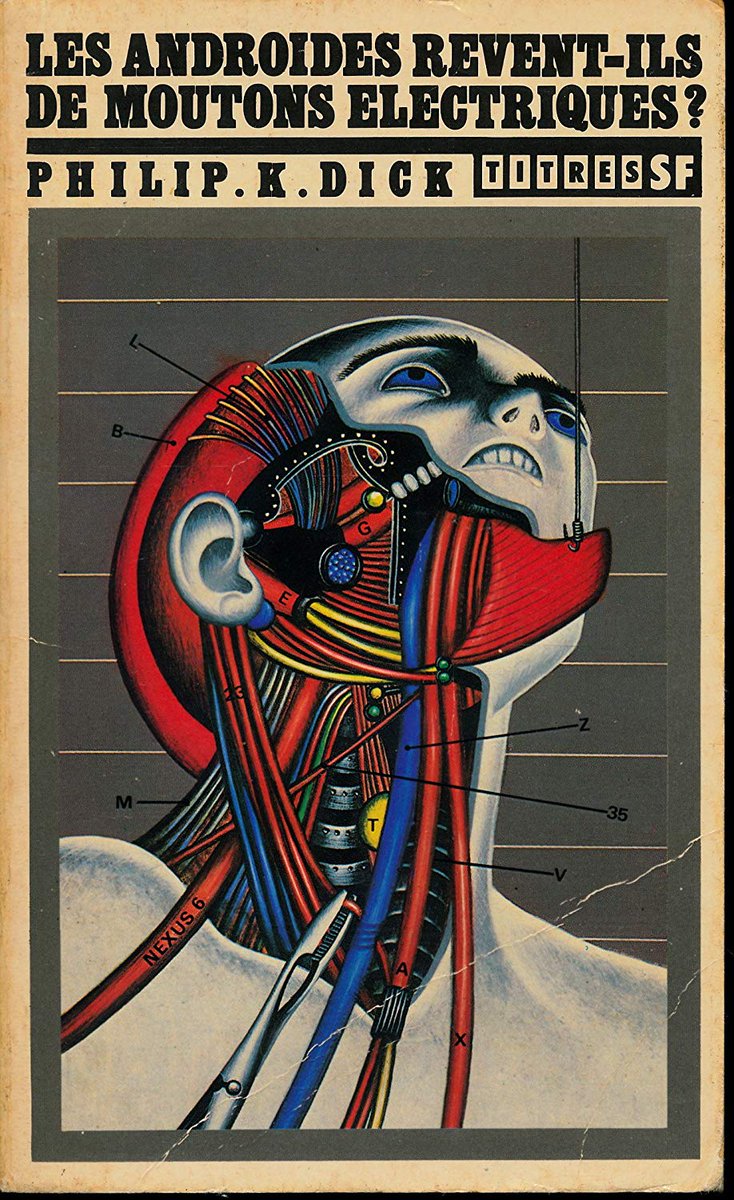

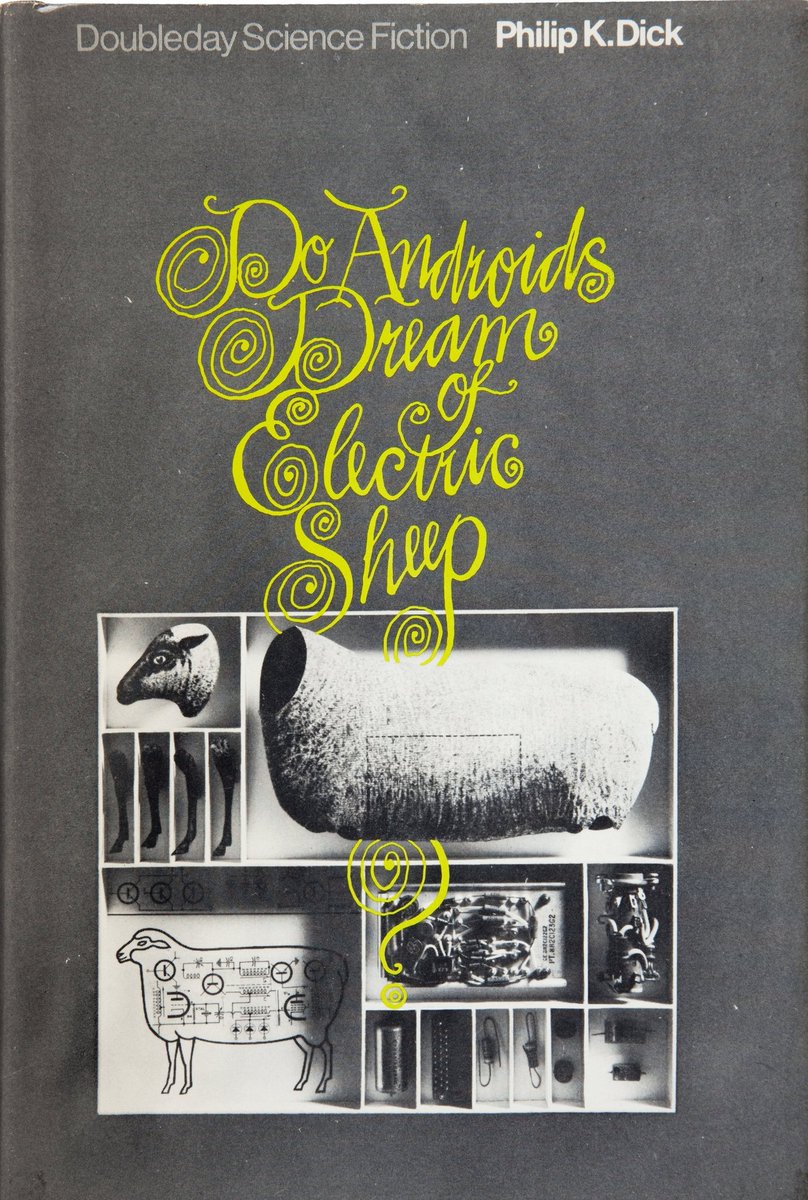

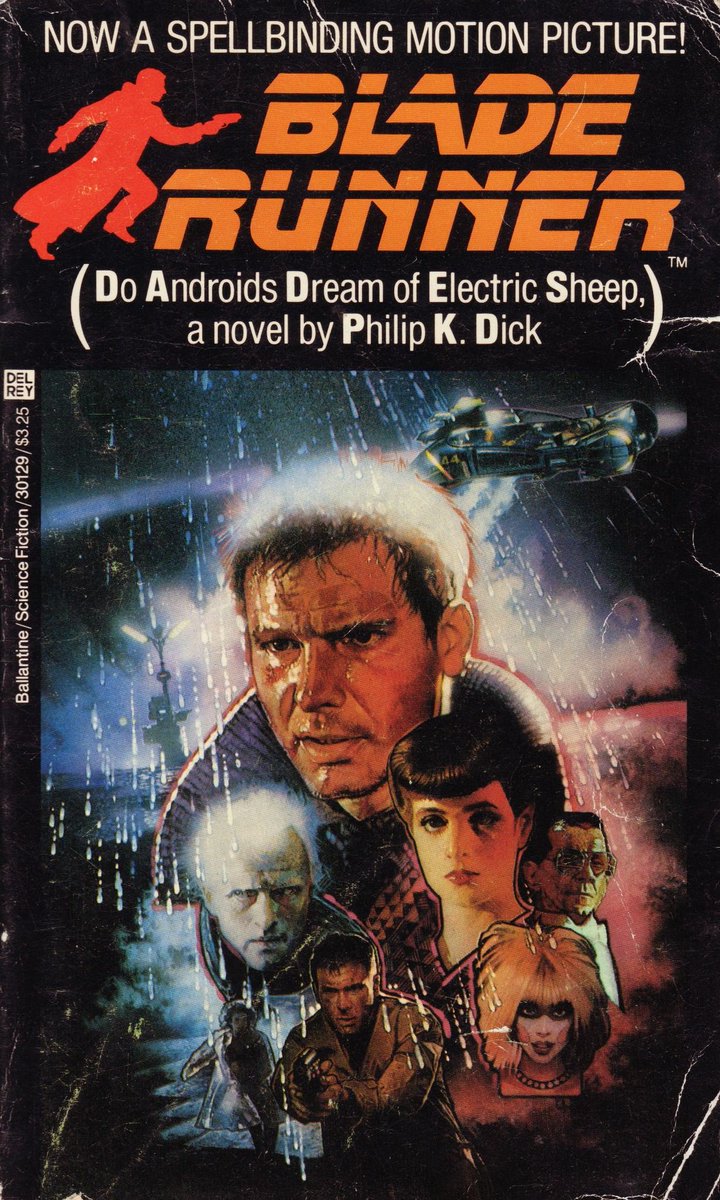

Blade Runner is based on Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? However 'inspired' may be a better word, as the film is very different to the book.

In the novel Deckard is a bounty hunter for the San Francisco police. The year is 1992; Earth has been ravaged by war and humans are moving to off-world colonies to protect their genetic integrity. They are given organic robots to help them, created by the Rosen Association.

Only the poor and the defective are left on Earth, along with replicants. Owning real animals – which are mostly extinct – has become a luxury pastime. Deckard owns an electric black-faced sheep, but dreams of having the money to buy a real animal.

There is a movement on Earth for greater empathy. Owning real animals is one way to achieve this, another is to use an ‘empathy box’ that links users to the collective suffering of a Sisyphus-like character called Wilbur Mercer.

Deckard is assigned to kill six Nexus-6 androids who have escaped from Mars and come to Earth. The Nexus-6 models are highly realistic replicants of humans, very difficult to detect. From his bounty he buys his wife a real Nubian goat.

The novel explores what (and who) is really human, what is ethical and what empathy really means. Rachel Rosen, a replicant ‘niece’ of Eldon Rosen, has a relationship with Deckard in the novel. Deckard himself is portrayed as a human who has empathy for replicants.

Throughout the 1970s a number of directors were interested in adapting Dick’s novel for the screen. Martin Scorsese was interested in but never optioned it. Producer Herb Jaffe did option it in the early 1970s, but Dick was unimpressed with the screenplay.

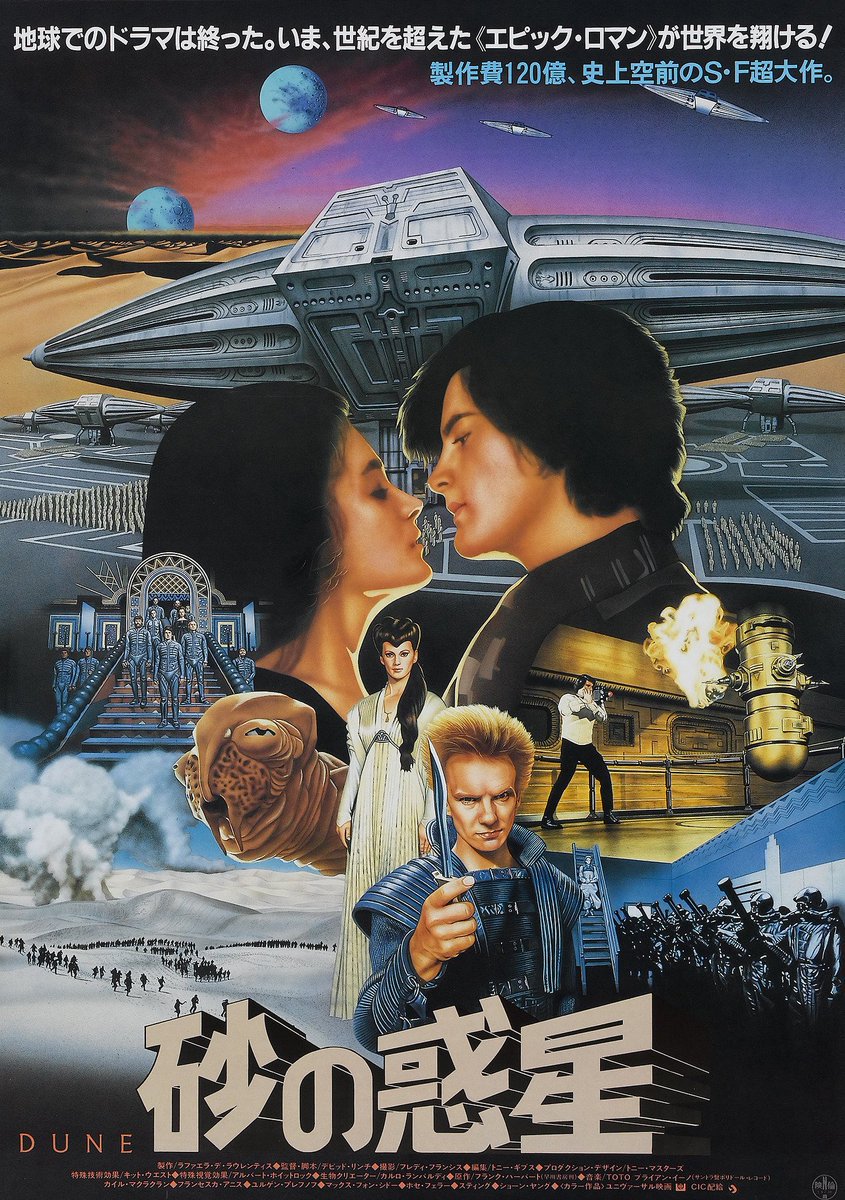

By 1977 Hampton Fancher had produced a workable screenplay and British producer Michael Deeley began gathering funds to film it. He also tempted Ridley Scott to direct it. Scott was working on the film version of Dune, but was growing disenchanted with its pre-production delays.

Fancher also made the decision to rename the film. He’d seen a script by William S. Burroghs, an adaption of Alan E Norse’s 1974 medical sci-fi novel The Bladerunner. Ridley Scott liked the title so they bought the rights.

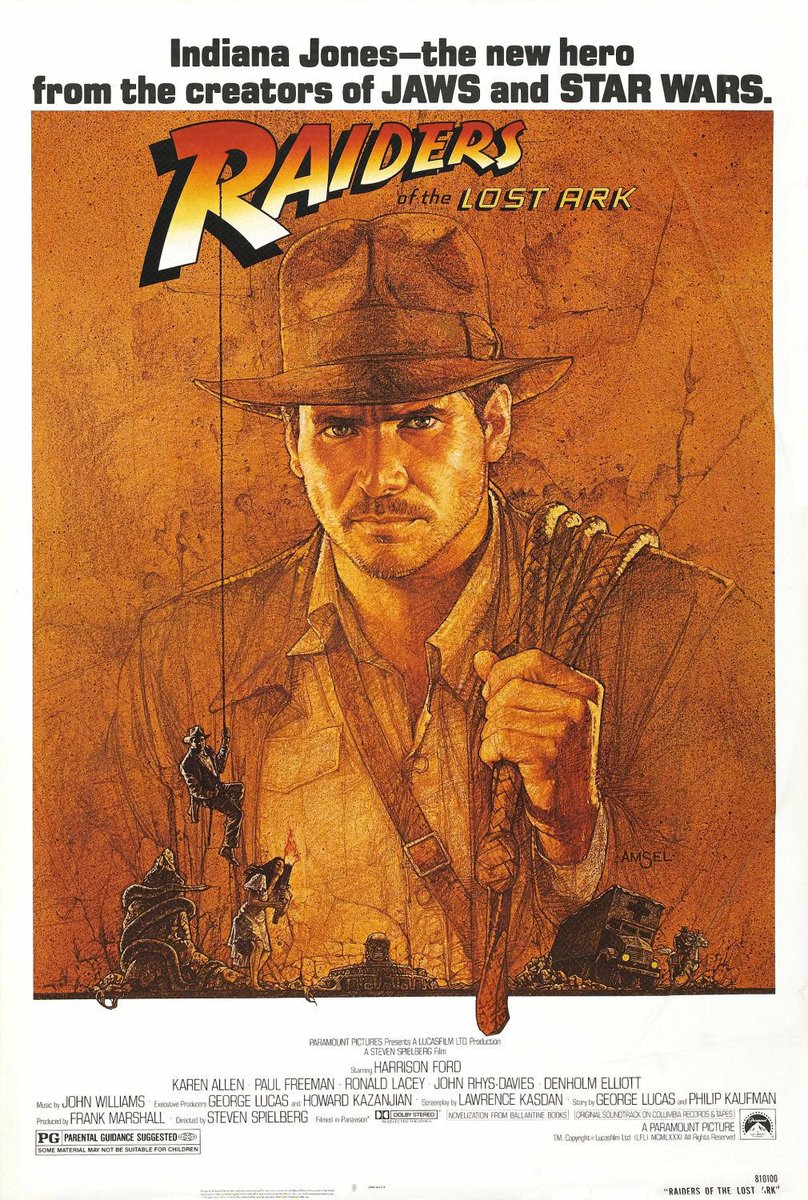

Many actors were considered for the role of Deckard in Blade Runner, including Dustin Hoffman, Burt Reynolds and Al Pacino. Harrison Ford was eventually chosen, partly because Steven Spielberg had highly praised him for his work on Raiders of the Lost Ark.

However the relationship between Scott and Ford proved tricky: Ford especially disliked the voiceovers he was made to do after the studio recut the film to have a ‘happier’ ending. He felt the film worked fine without them and was unhappy with recording this extra dialogue.

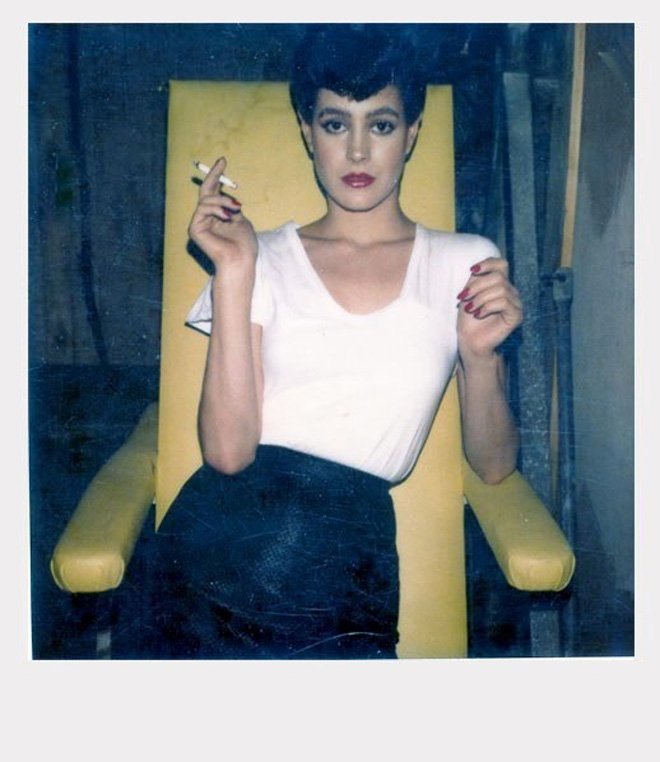

Sean Young was cast as Rachel, with Rutger Hauer playing the lead replicant Roy Batty. Hauer hugely enjoyed the role, and improvised his characters ‘tears in rain’ closing speech.

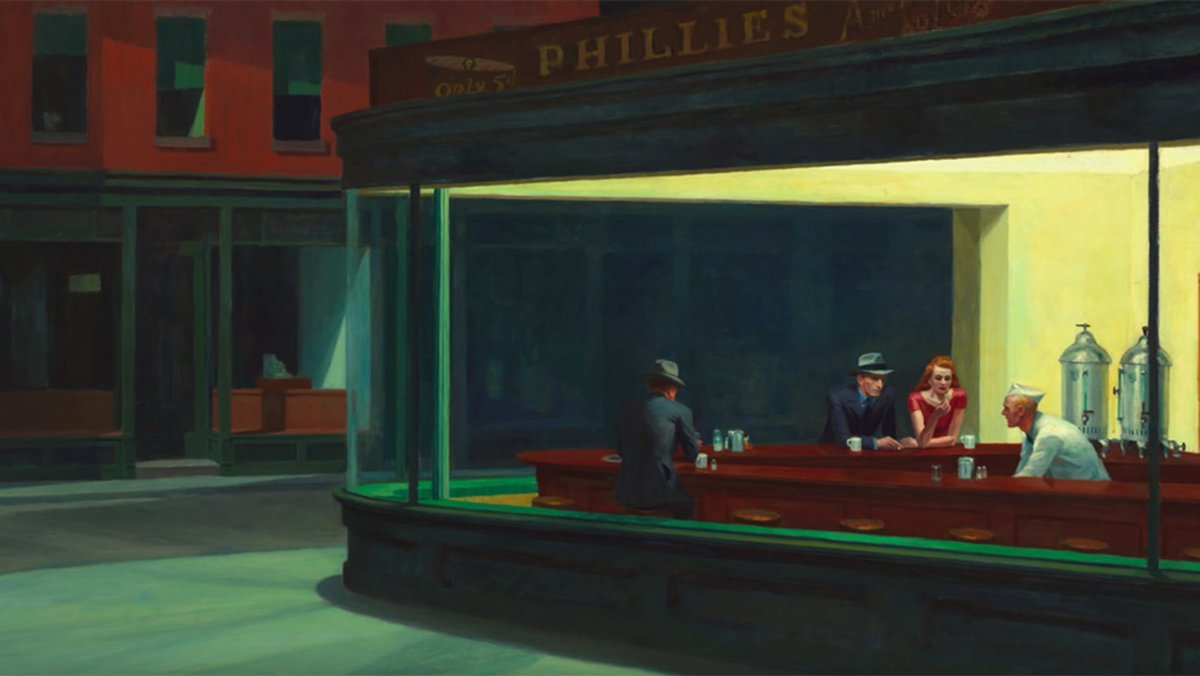

The film version of Dick’s novel is very much a tech-noir. Edward Hopper’s 1942 painting Nighthawks was a huge influence on the film’s style, as were the classic film noirs of the 1940s. Hampton Fancher wrote the part of Deckard with Robert Mitchum in mind; world-weary and stoic.

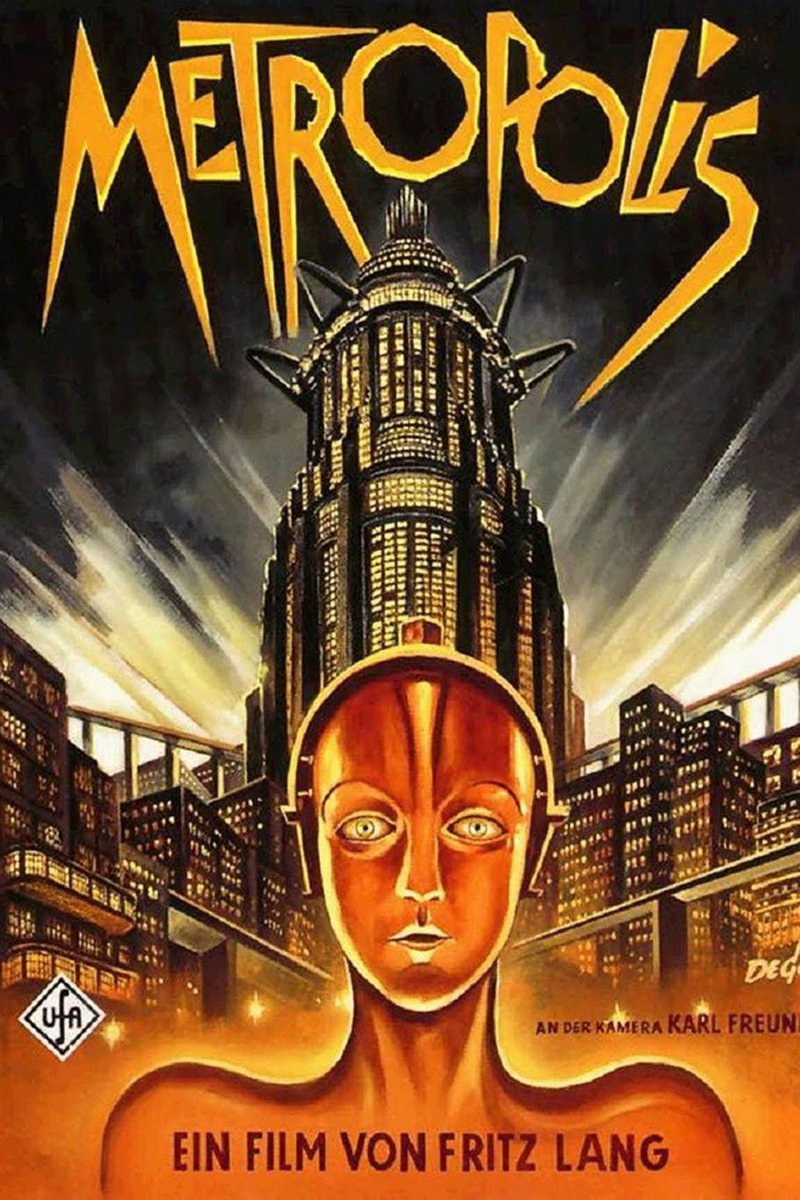

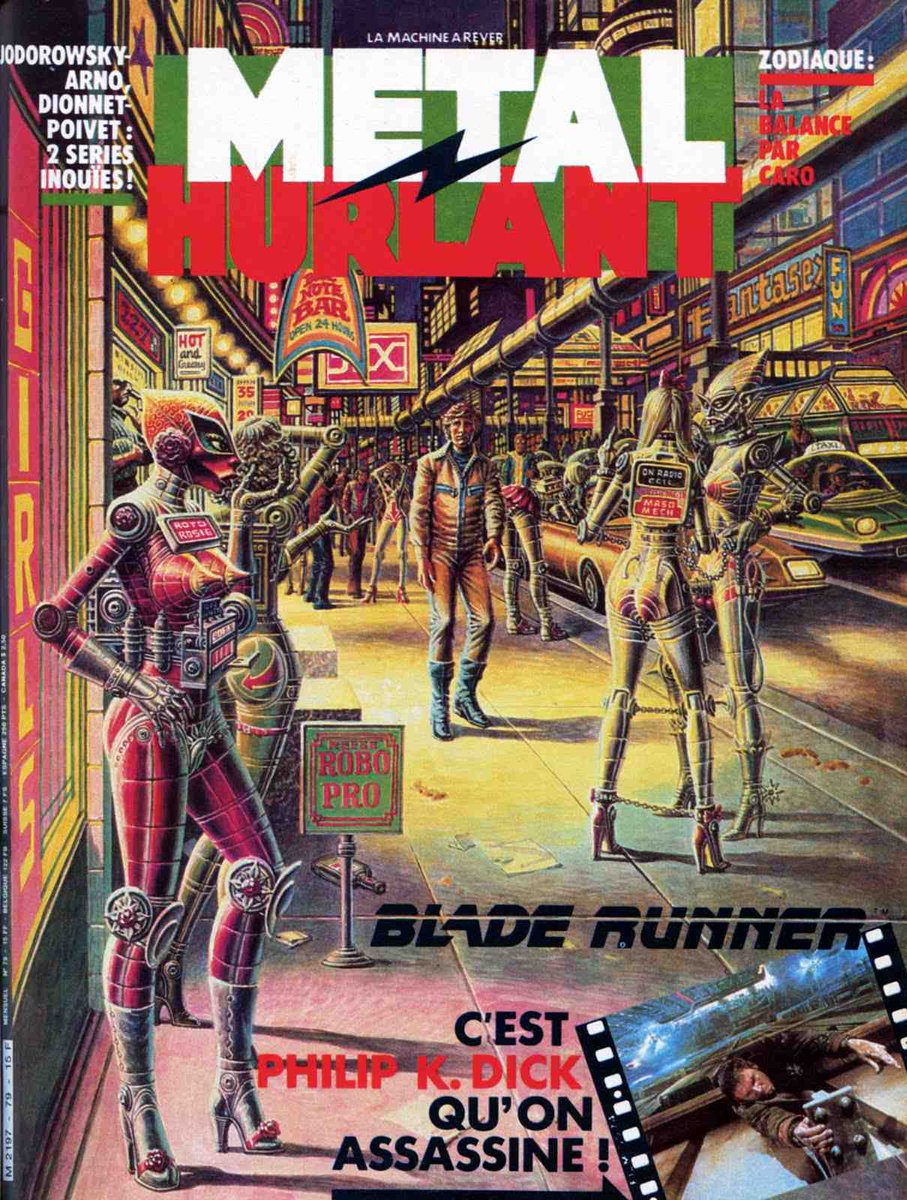

The visuals are something else: part Metropolis, part Métal Hurlant, they also reflect the giant ICI Wilton petrochemical plant close to Scott’s home town. Seeing it on night-time train journeys along the wind lashed Cleveland coast helped inspire Scott’s vision of LA in 2019.

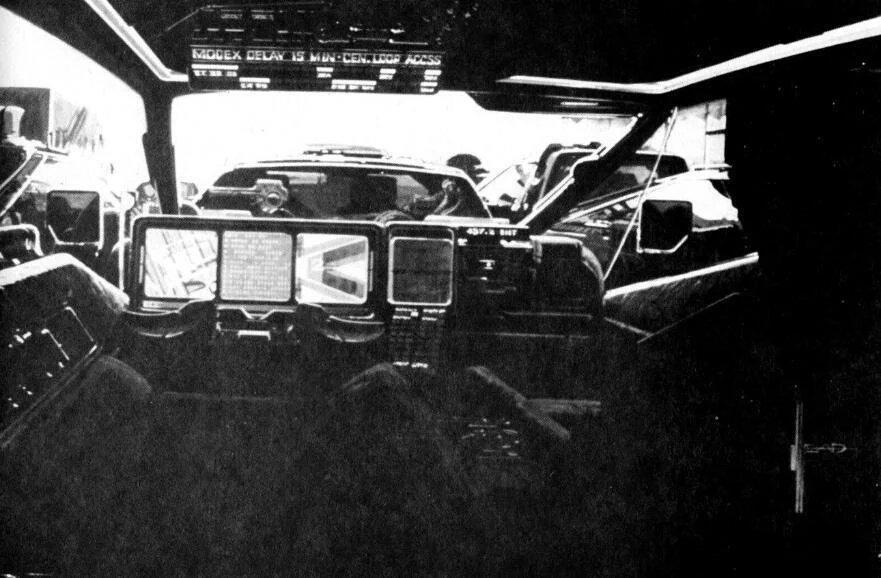

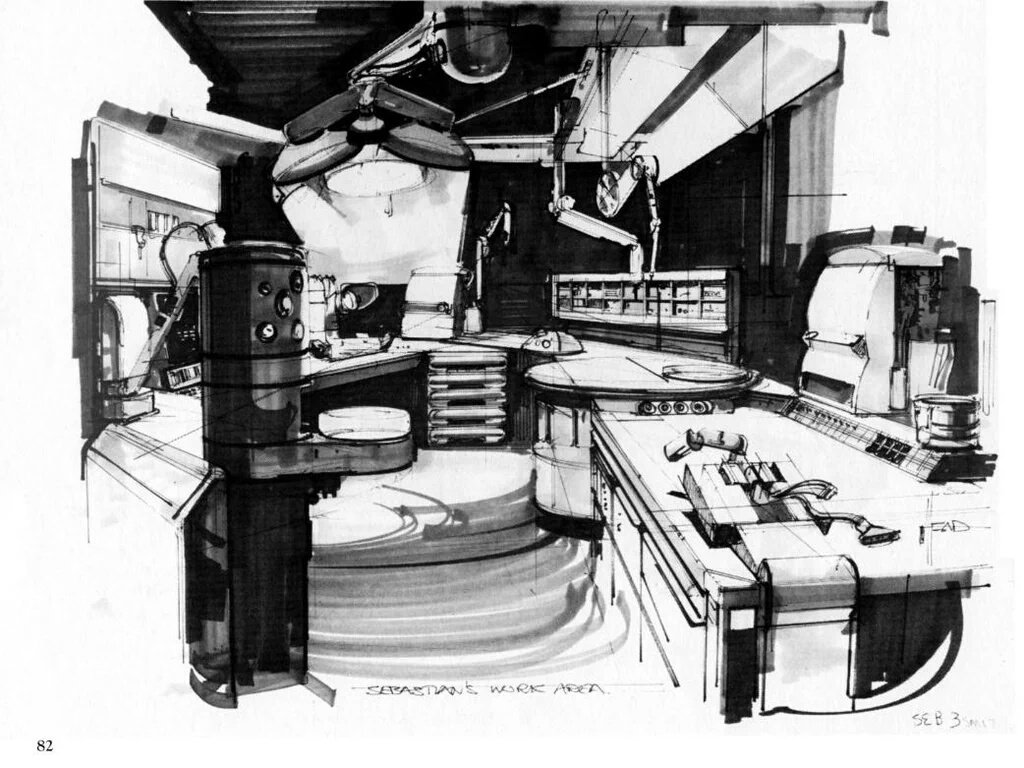

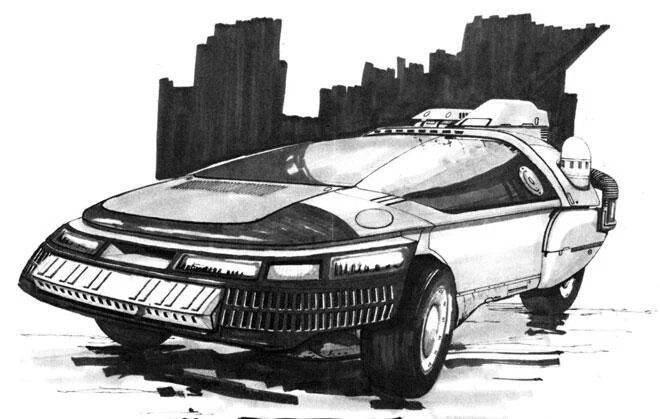

Syd Mead was the concept artist on Blade Runner and created detailed sketches of how he wanted every element of the world to look. Métal Hurlant artist Mœbius was asked to join the pre-production design work, but turned it down to work on the animated film Les Maîtres du Temps.

The music for Blade Runner was composed by Vangelis and its haunting, terrifying synthesiser score was nominated for a BAFTA award. The soundtrack album for Blade Runner was delayed for almost a decade, and has been sampled by many artists since.

Scott’s original edit of Blade Runner famously went over budget and time, and in response to poor test screenings the producers imposed their own cut of the film, along with the voiceovers that Ford so hated making. A Director’s Cut was issued in 1991 and a Final Cut in 2007.

Blade Runner launched to mixed reviews and so-so box office takings, but soon grew into a cult success. Many books, documentaries and even academic papers have been written about its themes and influences. It now has a well-deserved classic status.

But how does it stack up against Philip K Dick’s novel? The book (I think) is more of a meditation on the ethics and the effects of genetic engineering: what it means for our sense of self and how we relate to our world. The psychological development of Deckard carries the story.

The film is very much its own universe; a meditation on mortality as much as identity. But both the book and the film address a subject that feels very pressing: how do we authentically live in a world where we can now alter and create sentient life through artificial means.

Perhaps the best tribute to Blade Runner came from Philip K. Dick himself. Shortly before his death he saw a 20 minute test reel of the movie. “I recognised it immediately” he said. “It was my own interior world.”

More stories another time...

More stories another time...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter