This is an illustrated key to the genera of Gymnosperms. We have already covered several of them in the key to the families: Taxus (TL), Cephalotaxus (TR), Ginkgo (BL) and Araucaria (BR) with the various podocarps, cycads and gnetales, so we don’t need to do any more with these.

That just leaves 2 families to deal with. But what a pair of families they are: Pinaceae and Cupressaceae. The first thing to appreciate is just how variable the different genera within these families are from one another: here for instance, is Sequoiadendron (L) and Sequoia (R)

Again, still within Cupressaceae, here are the contrasting cones of Nootka Cypress (left, essentially spherical) and Eastern White-cedar (right; more cylindrical).

Within Pinaceae this time, there are huge differences between shoot morphology across the genera. The needles can be inserted singly as in Douglas Fir (left), or in bundles as in Monterey Pine (right)

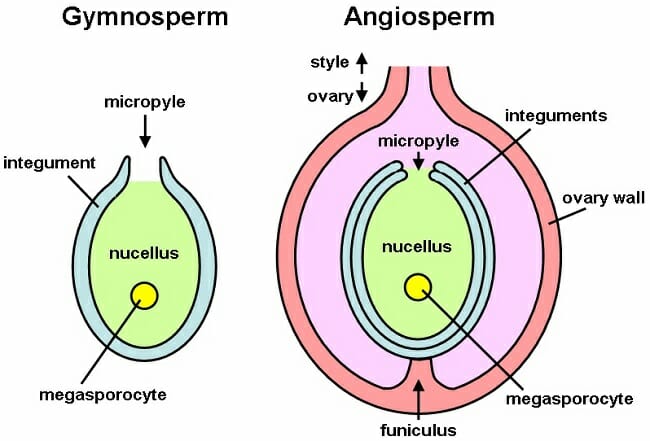

So if the genera are so variable within each family, what is it that makes Cupressaceae and Pinaceae distinctive ? This is where we need a bit of botany. Both Cupressaceae and Pinaceae are Gymnosperms, so both have naked ovules (left) attached to a cone scale.

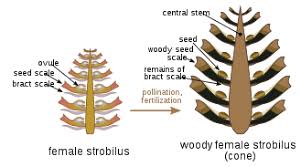

Below the cone scale bearing the naked ovule is a bract. The key thing to understand is that it is the relationship between this bract and the scale which sits above it, that defines the difference between the two families.

In Pinaceae (illustrated) the bract is free of the scale, and if you open a young cone you will find it. Older cones might have only a remnant, but there it is, none the less. So the female cones have readily distinguishable scales (with the seeds on them) and bracts (beneath).

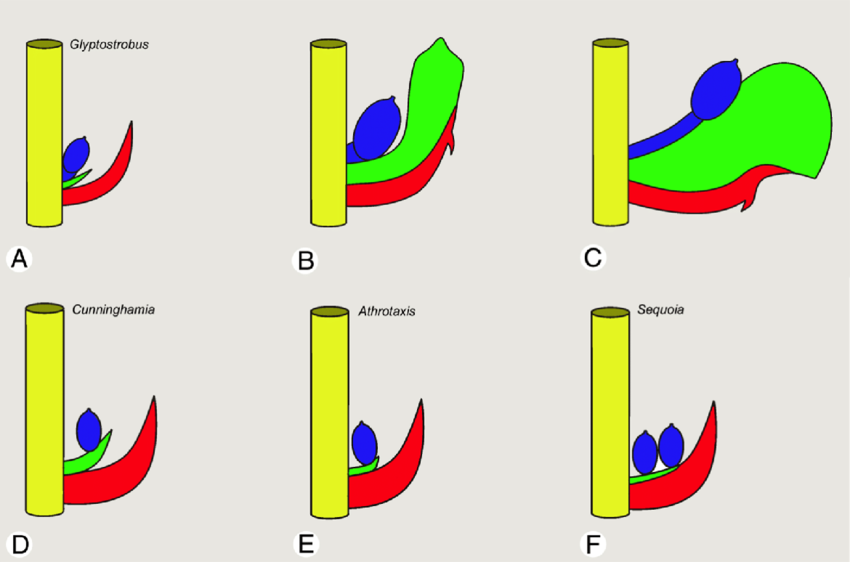

In contrast, in Cupressaceae (illustrated) the bract (red) is fused with the base of the scale (green), often to such a degree that you can’t tell them apart. The pattern of fusing is different in different genera (see below), but the story is the same. The ovule(s) are in blue.

So that’s what you need to try and remember: the two big Gymnosperm families are distinguished by a trait that is buried deep inside the female cone, invisible to casual inspection.

Fortunately, there is another, easier feature: Pinaceae have vegetative buds with proper bud-scales (left); Cupressaceae don’t have proper bud scales (right)

Now you are ready to embark on the key to the genera of Gymnosperms. Bear in mind that the first question in the key is much the hardest. Once we have separated Pinaceae from Cupressaceae it is relatively plain sailing (or plane sailing for the more pedantic). So don’t give up.

Buds with brown scales (left), and female cones with a free bract beneath the seed scale: Pinaceae (skip down)

Buds without proper bud scales (right), female cones lacking free bracts: Cupressaceae (next tweet)

Buds without proper bud scales (right), female cones lacking free bracts: Cupressaceae (next tweet)

Scale-like leaves in opposite pairs (left) or in 3s at each node (skip down)

Leaves 1 at each node and borne spirally (right) but often apparently 2-ranked (Taxodiaceae as was; next tweet).

Leaves 1 at each node and borne spirally (right) but often apparently 2-ranked (Taxodiaceae as was; next tweet).

This next part of the key involves what used to be the family Taxodiacea. Modern molecular work demonstrated that the members of this group could not be satisfactorily distinguished from Cupressaceae, so the two were lumped together.

The first question hives off the very distinctive genus Sciadopitys with its whorls of thick needles at the nodes (left), and big (5-10cm) cones that look like they have a chrysalis resting in the joins (right)

Next, we separate two groups on the basis of their leaves: are they in 2 spreading ranks (left) or closely appressed or in distinct spirals (right)

First we deal with the genera with leaves in 2 spreading ranks. Cunninghamia is very distinctive with its huge (>3cm) stiff, glossy, spine-tipped leaves

Next, measure the width of the needle-like leaves; if they are close to 1mm wide you have Taxodium. The leafy shoots should look tapered from base to apex (left). Broader needles (< 1cm) is something else (next tweet). The cones are almost spherical and lumpy (right)

The next question's easy: do you have Sequoia (dark green & evergreen, left) or Metasequoia (pale green and deciduous, right)? The latter is the common tree in modern up-market street planting like Canary Wharf and Kensington Olympia. The leafy shoots look as if they're opposite

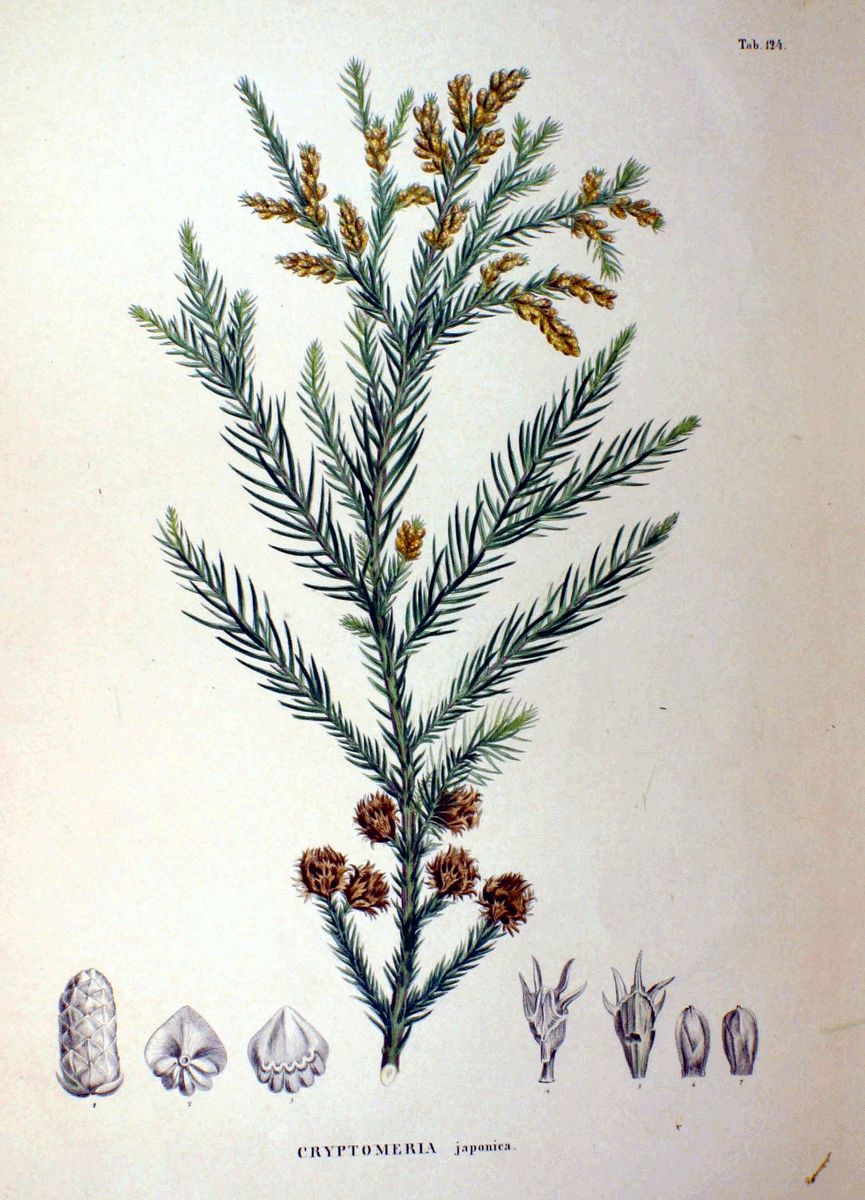

Now for the genera that don't have their leaves in two ranks. Measure leaf length. Stiff leaves, angled on the back, longer than 1cm are Cryptomeria (L). Otherwise next tweet. You will often see this genus as C. japonica 'Elegans' with very narrow, often bronzy foliage (R).

Finally in this section of the key we distinguish between the small Athrotaxis (L) and the giant Sequoiadendron (TR). The technical distinction is on the leaves: incurved or scale-like (left) or short and divergent (TR). Athrotaxis cones are bristly (BR)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter