With the Path to Sustainable Farming document released with its emphasis on co-design of policy, it seems incumbent on us as farmers to try and help make the end product the best it can be. So that's what this thread will try to do in a small way.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/939925/agricultural-transition-plan.pdf

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/939925/agricultural-transition-plan.pdf

Following an excellent webinar with @JanetHughes (and her cat); some great  s from @jojabaker and @HawfordFarm; and @CommonsEFRA committee sessions with @TamFinkelstein and @DKennedyFFaB, it's clear there's a passionate team who've worked v hard. So thank you all for that.

s from @jojabaker and @HawfordFarm; and @CommonsEFRA committee sessions with @TamFinkelstein and @DKennedyFFaB, it's clear there's a passionate team who've worked v hard. So thank you all for that.

s from @jojabaker and @HawfordFarm; and @CommonsEFRA committee sessions with @TamFinkelstein and @DKennedyFFaB, it's clear there's a passionate team who've worked v hard. So thank you all for that.

s from @jojabaker and @HawfordFarm; and @CommonsEFRA committee sessions with @TamFinkelstein and @DKennedyFFaB, it's clear there's a passionate team who've worked v hard. So thank you all for that.

I want to pick out a few issues – both broad and narrow – to try and strength test them for robustness.

There's a lot of research work out there gathering dust, which often can help to teach lessons and avoid mistakes before they are made.

There's a lot of research work out there gathering dust, which often can help to teach lessons and avoid mistakes before they are made.

The first is the issue of income foregone (IF). When you look into it, it gets quite complicated quite quickly.

To start, recall the Feed in Tariff scheme where payments were set at a flat rate according to bands of installed capacity.

To start, recall the Feed in Tariff scheme where payments were set at a flat rate according to bands of installed capacity.

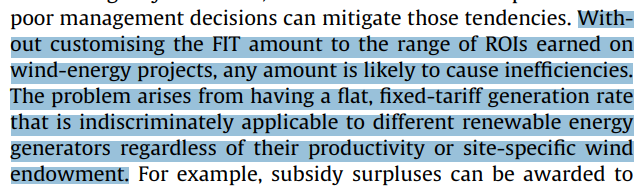

FiTs were insensitive to individual sites' wind resources, which, because of the need for the lowest desirable wind speed to generate acceptable returns, generated excess returns for projects with high wind resources:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421511004472.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421511004472.

How does this relate to the design of ELM policy. To see this consider the following paper:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2008.00183.x.

Analogous to renewable sites, this recognises that every farmer will have their own set of characteristics.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1477-9552.2008.00183.x.

Analogous to renewable sites, this recognises that every farmer will have their own set of characteristics.

These include land productivity, farmer attitude, soil type, ability to restructure fixed costs, etc.

Each farmer has a unique set of characteristics which determines their willingness to implement environmental options on their land as the prices of those options vary.

Each farmer has a unique set of characteristics which determines their willingness to implement environmental options on their land as the prices of those options vary.

As with FiTs, this paper shows how differences in individual circumstances can result in a misallocation of resources with a flat option payment rate.

It also recognises that option delivery does not have the same public value in all locations, which worsens the problem.

It also recognises that option delivery does not have the same public value in all locations, which worsens the problem.

Previous schemes have addressed this 2nd issue with limits on where options can be used (e.g. only on parcels at risk of erosion), and have introduced different tiers + levels to scheme design.

However, I want to look at the difference in farmer characteristics a bit more.

However, I want to look at the difference in farmer characteristics a bit more.

This is another paper which looks in a more complicated way at the relationship between option price, ecosystem services delivery and agricultural outputs:

https://academic.oup.com/erae/article-abstract/40/4/573/428178.

https://academic.oup.com/erae/article-abstract/40/4/573/428178.

There are two features in this paper that caught my eye.

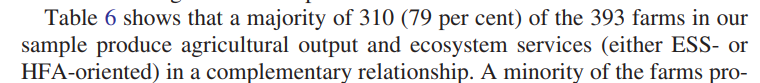

Firstly, the idea of complementary, supplementary and competitive relationships between environmental options and agricultural output, and how this might tie into components within ELM.

Firstly, the idea of complementary, supplementary and competitive relationships between environmental options and agricultural output, and how this might tie into components within ELM.

For one farm scheme delivery could complement their existing agricultural output; for another delivery of the same scheme could supplement it; and for a 3rd it could compete with it.

To see this, look at one Mid Tier option: winter cover crops (SW6). Imagine a heavy land farm. Winter cover crop could impact spring crop establishment & yield. The more ecosystem services, the less agricultural output. A competitive relationship.

However, a light land farm with grazing sheep could increase the yield of their spring crops due to increased moisture retention and provide forage for the sheep. A complementary relationship.

But at higher areas it could become competitive again if displacing winter crops.

But at higher areas it could become competitive again if displacing winter crops.

Results show plenty of evidence of complementary relationship between environmental scheme output and ag output for most farms. Whether this is something to aim for particularly with the Sustainable Farming Incentive taken as a whole?

It's interesting also that when delivering two schemes (HFA & CSS) on the same farm that the relationship between the outputs was mainly competitive or supplementary. Again, interesting to see whether interaction between the 2 lower ELM components must necessarily be competitive.

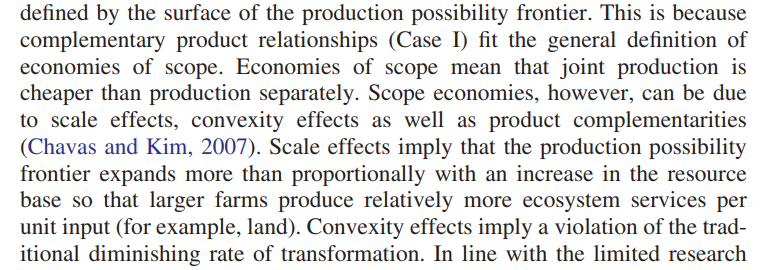

The concepts of convexity effects, scale effects and economies of scope are v intriguing. I suppose it points to the possibility of highly non-linear supply behaviour with increasing flat rate pricing.

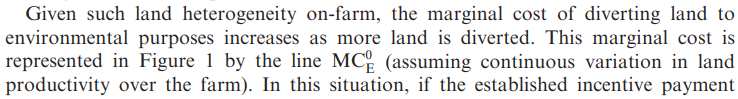

Linked to this, Fraser assumed the marginal cost of diverting land environmental options was continuous and linear (due to continuous variation in land productivity), but this isn't necessarily true. Particularly with rotational options, there can be threshold effects.

With the existence of non-linearity or thresholds, the sensitivity of land diversion to ELM with price changes could be very high and be highly heterogenous between farmers. The ability to restructure fixed costs could have a large bearing for example.

This returns to the interaction in social value of option delivery & spatial distribution. Is DEFRA happy for options to be delivered at the lowest cost, even if this means it is highly concentrated on farms who either can engineer complementarity / low opportunity cost?

If not, are they happy to pay these farms too much to ensure more even spatial distribution, or are they going attempt the 2nd paper's method of generating a sophisticated model with very granular detail to optimise payment rates between regions / farmers / soil types etc?

If they do go down this route, will need quite a bit of pilot trials data to come in & some good stats bods. Also will need to bear in mind the increased scheme complexity and tension with the drive to simplify schemes and administrative burdens.

That's one way of looking at determining payment rates. Another requires a complete reframing of the process into the world of negotiation. Time to think in terms of BATNAs and ZOPAs.

To follow.

To follow.

In The Path to Sustainable farming document there are 12 mentions of the word "fair". Mostly they are in the context of the aim of making things "fair and reasonable".

So what should be understood by the word fair in this context? Suppose your teenage self is trying to agree with a neighbour how much they will pay you to mow their lawn. What are the relevant things to consider here?

Negotiation theory says that two key pieces are both sides' BATNA, or Best Alternative To No Agreement. The name is pretty self-explanatory. The space between both sides' BATNA is known as the ZOPA, or Zone Of Possible Agreement.

The aim for the teenager is to strike a deal that lies as close to the other side's BATNA as possible. For the lawn owner, the reverse is true. The BATNA for the teenager can depend on many things, but how much (s)he needs the money and who else wants their lawn mowing are key.

For the lawn owner, how badly they need their lawn mowing and then next most expensive way of achieving this are also going to be important.

Let's think about the extent to which this situation is analogous the development of the post-Brexit farming policy.

Let's think about the extent to which this situation is analogous the development of the post-Brexit farming policy.

Let's think first about the BATNA of English farmers. As discussed above, this is going to be different in each individual case, but generally it's going to be the profitability of farming without engaging with ELM, or by engaging with something like ELM offered by another party.

That something like ELM from another party offer is not presently obvious, at least to me. I can see things like this competing in time, but it's at quite a nascent stage:

https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/294977-0.

https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/294977-0.

What about the government though, what is their BATNA? Simplify for a moment and assume all English farmers were one entity. If the ELM scheme was roundly rejected by the corpus of English farmers, how bad would that be for the government?

To achieve our net zero goals and the targets set out in the 25 year environment plan, the government needs farmers to put in a lot of work to achieve this. Neither is possible without farmers. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/25-year-environment-plan/25-year-environment-plan-our-targets-at-a-glance

If the government were in the same position as the neighbouring lawn owner, the BATNA would look pretty bad. The reason this analogy doesn't quite fit is the secret weapon the government has: regulation. It's like the lawn owner being your parents who can confiscate your Xbox.

As an aside, the other reality is the English farmers are not one entity. In most of our negotiations our inability to negotiate in larger blocks leads to poorer negotiating outcomes.

The problem with the farmers' BATNA is that it's just about to take a pasting. With commentators predicting the probability of no deal around 40-80% & its dire effects, & with the now announced reduction of BPS without replacement, farmers are right to expect a tough time ahead.

So, framing the current process as an form of negotiation, this leaves a large ZOPA.

To return to the start of today's waffling, the question then is in the light of this framework, where in this ZOPA is a deal that is "fair"?

To return to the start of today's waffling, the question then is in the light of this framework, where in this ZOPA is a deal that is "fair"?

Chris Voss, my favourite hostage negotiator*, describes the word fair as the most powerful word in negotiations. He makes this further comment in his piece on the word here:

https://www.fastcompany.com/3060582/the-one-word-that-can-transform-your-negotiating-skills.

*Easy to say – I only know of one.

https://www.fastcompany.com/3060582/the-one-word-that-can-transform-your-negotiating-skills.

*Easy to say – I only know of one.

The Capuchin monkey experiment is already famous, but it so nicely demonstrates this effect.

It is similar to the Ultimatum Game played with humans:

.

So to work out again how this compares to the current farming situation, a bit more context is needed.

.

So to work out again how this compares to the current farming situation, a bit more context is needed.

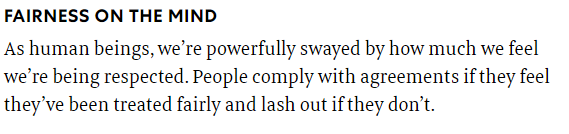

We know from the voluminous DEFRA evidence compendium (p.115) that for every £1 spent on Countryside Stewardship the public received £3.60 back in benefits.

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/834432/evidence-compendium-26sep19.pdf

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/834432/evidence-compendium-26sep19.pdf

And what did the farmers get? Well they got pretty much their BATNA – i.e. income foregone. That is, they were given very little of the value within the ZOPA; often weren't paid on time; had a v. one-sided contractual agreement; and were penalised for minor mistakes.

@HawfordFarm makes a number of points here about IF, and I have some sympathy with them; however, I think there are some further points to make.

https://twitter.com/HawfordFarm/status/1333156271353163783.

https://twitter.com/HawfordFarm/status/1333156271353163783.

1/ The BPS reductions are not surprising, but I think the concern is the asymmetry between clarity on cuts to funding without a corresponding clarity on the detail of ELM. We were promised more detail by now on the latter.

2/ Yes, old schemes used IF, but a) the ambition is for well in excess of 52k agreements; b) value of public goods delivered is higher now, I would argue, than at time of previous schemes & set to increase; and c) reality of costs saved+cost incurred often does not match theory.

3/ Would be interesting to understand more what is meant by "overheard cost allowances".

4/ This is strong point, but see points later about farm subsidies in competitor countries.

4/ This is strong point, but see points later about farm subsidies in competitor countries.

5/ It may be voluntary, but farmers feel that if they don't take the  , a stick (regulation) might be wielded.

, a stick (regulation) might be wielded.

As for not being a right, no, but the concept of capturing a fair share of the reward is pertinent here. N.B. "achieve more for farmers" too, not just environment!

, a stick (regulation) might be wielded.

, a stick (regulation) might be wielded. As for not being a right, no, but the concept of capturing a fair share of the reward is pertinent here. N.B. "achieve more for farmers" too, not just environment!

6/ The idea here of it being all about the fit and not about the money is wishful thinking IMO. How it dovetails is important (see points in video below), but the payment levels really matter. To repeat @Minette_Batters' line: "You can't go green if you're in the red".

7a/ First, we were told it would be IF plus additional margin here (with recognition that IF rates are "very low" meaning only marginal land suitable):

https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/71677323-1403-40eb-a0ec-1ac1764a125f?in=15:39:24&out=15:40:56.

https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/71677323-1403-40eb-a0ec-1ac1764a125f?in=15:39:24&out=15:40:56.

7b/ Second, in the long run ELM doesn't replace BPS, but in the short-term it kind of does (given the manifesto commitment). See here, again from @DKennedyFFaB (sorry to tag you so much!):

https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/71677323-1403-40eb-a0ec-1ac1764a125f?in=15:23:11&out=15:25:11.

https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/71677323-1403-40eb-a0ec-1ac1764a125f?in=15:23:11&out=15:25:11.

7c/ I think @Minette_Batters and @ProagriLtd should be pushing that if ELM + other schemes fail to take up the slack here, this should be returned to the BPS pot in order provide stability and stick to the manifesto pledge.

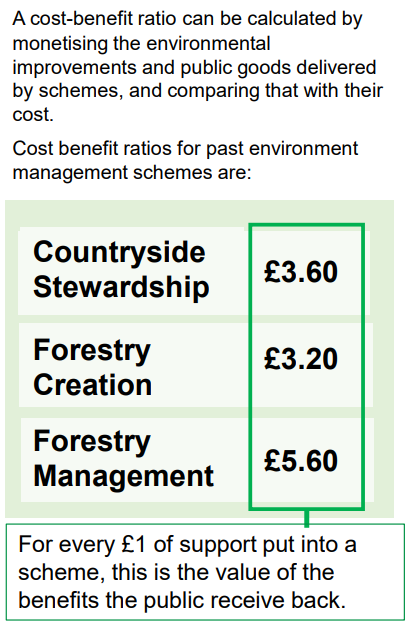

(Source: p.26, The Path to Sustainable Farming.)

(Source: p.26, The Path to Sustainable Farming.)

8/ I think @herdyshepherd1 makes the point nicely in this piece: https://unherd.com/2020/12/brexit-will-ruin-britains-farms/.

That is, we are being asked to produce things in competition with others who are subsidised. You cannot simply divorce the two issues and class one as a distraction.

That is, we are being asked to produce things in competition with others who are subsidised. You cannot simply divorce the two issues and class one as a distraction.

9/ This point runs both ways. Do not over-promise and under-deliver right at the start (see earlier points on IF) & rush the timetable. And avoid coming in with low ball offers thereby putting people's backs up (Jeremy Hunt and junior doctor contracts anyone?).

To continue [email protected] ( @JanetHughes), a change of tack to the more specific: payment by results and soil sampling. A pet subject of mine.

I want to argue that paying farmers for building carbon in their soils should NOT be done using on-farm soil sampling.

I want to argue that paying farmers for building carbon in their soils should NOT be done using on-farm soil sampling.

Instead I want to argue the best way to do it is to rely on a comprehensive literature review and identify practices that tend to build carbon, and then pay farmers to undertake these practices.

I'm going to apologise in advance for being a bit negative here, but it's a very important issue that will affect me personally and all other farmers. I absolutely want to focus here on the argument and not people making it.

This is a study that I think shows everything that is wrong about this issue:

https://twitter.com/soilhealthexprt/status/1330791194050392065.

To see why, look at my comments below about sampling depth.

https://twitter.com/soilhealthexprt/status/1330791194050392065.

To see why, look at my comments below about sampling depth.

It is clear to me that the evidence shows you MUST sample to much deeper than done in this study to get an accurate picture. Given this study has failed to do this, the conclusions drawn are not valid IMO. Indeed, I think the evidence on balance shows the reverse.

That is, there is not a good proxy test or soil sampling test that could be done by a farmer to judge whether they have sequestered carbon or not. Maybe for other things like aggregation, stratification etc., but not for carbon sequestration.

The fatal flaw in this study happens a lot with farmers. We see a lot of claims about how much more SOM / SOC a pet method of farming has helped create. In nearly all cases, I think they do not have sufficient evidence to make these claims that they would like to be true.

This links into another point for @JanetHughes & DEFRA. I think your Evidence Compendium was great. I enjoyed reading all of it. I think you need to create a similar one for the specific options within policies that you design.

In most cases the necessary research work has already been done. It just needs unearthing and summarising. It's often counterproductive to fund new work done to a lower standard when the answers already exist.

My particular worry here is, if government policy is at all following the thinking of those like Dieter Helm where natural sequestration is the backbone of the strategy, we can't afford to get 10 years down the line and realise all the carbon we think we've created is a mirage.

The issue with doing things that tend to sequester carbon is that not every farmer doing these things will achieve this. Some buffer will need to be built in to account for this. But this can happen with on-farm measurements too, so not an issue unique to either approach.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter