I did an earlier very long thread telling the roundabout story about how I broke in as a TV writer at 35 while living in Seattle. I'll try to tell the next chapter: starting off my career writing and developing for TV and trying to stay somewhat afloat in my first year. https://twitter.com/tonytost/status/1331359403941847040

My initial thread had a bit of an underdog narrative: going from growing up in a trailer park to becoming a writer in Hollywood. This very long thread doesn't really have that. It's more about the crusty details about the difficulty of finding my footing once I got my big break.

This isn't meant as advice or as exemplary. More like some data points if you're trying to figure your own path. Back in the day, my wife and I found John August's blog to be invaluable in terms of figuring out this new landscape. Maybe these threads can pay that back a little...

After my first round of meetings in LA, I returned to Seattle with a gig freelancing two episodes for LONGMIRE, plus 3 separate pilot deals set up at 3 separate studios. Months earlier, I was a poet and academic who'd never written an entire script. Suddenly, I was a TV writer.

Some of the chronology is fuzzy, but I believe the 1st step after my initial trip was the studio trying to gauge interest in TANGLE EYE, the pilot I'd written to break in. The studio sent it around to some networks, but there wasn't enough interest to even pitch it around town.

The studio also sent the pilot to a pretty famous edgy macho showrunner as a possible godfather type figure for the show. He dug the writing and loved the characters, but didn't feel it would sustain over an entire series (he was probably right). He politely passed.

With a creative exec at the studio, I continued developing TANGLE EYE, but it never fully clicked. We tried foregrounding a sheriff as an antagonist, but that just ended up slowing down the story and numbing the emotional impact. The more we developed it, the worse it got.

By the terms of my deal, I wouldn't be paid for TANGLE EYE unless it sold to a network. So, no $. But it was part of a two-pilot deal. So in the back of my mind I tried to formulate potential ideas for the 2nd pilot, while the studio would pitch me occasional ideas for pilot #2.

At this point, I don't think I did anything "wrong" with TANGLE EYE. I'd written it to help me break into the industry and it helped me do exactly that. Not every project is going to succeed.

To be honest, the pilot was conceived less as a starting point for a TV series than as an emotionally-charged, uniquely-textured, fairly muscular 55 page introductory letter for myself as a TV writer. Having it actually go on to be more than that would've been a crazy bonus.

Anyway, I also started the process of working on LONGMIRE. The writer's room for that show was unique. The showrunner was Greer Shephard, who is not a writer, but who is an immensely gifted storyteller and is involved at every tiny step of the writing process.

The head writers were also EPs -- a writing team of Hunt Baldwin and John Coveny. In essence, the show was run by the three of them, but with Greer as the ultimate authority and unifying sensibility.

In S1, I was the show's lone freelancer. There were two other staff-level writers on the show. I now realize it was a very non-ordinary writer's room: the EP trio would break each episode and only the writer assigned to write that episode was brought into the room with them.

The other lower level writers would stay at home until their next episode came up in the rotation. So, if it was an episode I was scheduled to write, I would be the only lower level writer in the room with the EP trio.

As a beginning writer, I think this room setup was more of a plus than a minus. I think one of the big anxieties for a first-time TV writer is how to navigate the social and political dynamics of a room when there are varying levels of power and differently-tuned egos and such.

Having no industry experience, I was curious and anxious about how I would slide into such a dynamic. Thankfully, the power dynamic between three EPs and me, the lone freelancer, was so clearly lopsided I could pitch tons of ideas without stepping on any toes.

Which was good. I'm generally a quiet, keep-to-myself type of guy. But I'm not shy. I just don't like talking that much. Except for when I'm in a writer's room or writer's workshop type environment. Then, I sorta have trouble shutting up (e.g., these threads).

Therefore, a traditional writer's room could've been full of landmines for beginner me. But thankfully, with the LONGMIRE room's set-up, it was sort of my job from the get-go to be very vocal and to drive a lot of the breaking of my two episodes.

In most rooms, I would've been expected to talk 90% less than I did in the LONGMIRE room. I don't know how well I would actually function as a low-level writer in a traditional room: I'm full of opinions, & I don't hesitate to say what I actually think. Tactfully, I hope.

Anyway, for S1, I was assigned episodes 105 & 107. For 105, I flew down to LA for two weeks, staying at an old hotel just down the street from the studio. Each day I'd arrive in our tiny writer's room and we'd begin brainstorming and breaking the story for my episode.

My philosophy was to be "low maintenance, high performance." That is, to suck up as little mental and emotional energy from the EPs as possible. To be a positive presence in the room. To not mistake it for a therapy session. To bring zero drama.

After each day in the room, I'd spend the evening researching until I came up with either a couple of good story pitches for the next day. I didn't even bother with exploring LA. I just wanted to come in each day with something specific to pitch or add to the story.

For example: going into my first episode, the EPs knew they wanted to feature a Cheyenne vigilante who the people on the Rez would pay to get justice, since the court system was so useless for them. The EPs sent me some news articles for context, which helped a lot.

We realized that this Cheyenne vigilante figure (we named him Hector) was taking on a sort of mythic shape. In brief: he's suspected of stealing back Cheyenne children from a governmental child protection system that parents on the Rez didn't trust.

As the ep developed, I researched Cheyenne legends, hoping to give some specificity to Hector's mythic figuration. (I didn't want to fall into vague mysticism.) References to the historical Dog Soldiers caught my eye (I loved Robert Stone's novel by that same name).

The more I read about the Dog Soldiers, the more I realized that this was probably the perfect mythic precedent for Hector. I brought this information into the room the next day, along with some pitches to help the story accommodate the new info.

The EPs really loved this direction. My episode would end up being called "Dog Soldier," and the show's mythology of Hector and the Dog Soldier would become a central throughline for the show's entire six season run.

Each day for two weeks, we'd keep revising and refining the major beats of the episode, figuring out how to tell a cool mystery that had thematic integrity and that would also give a viewer a glimpse into life in Wyoming that would otherwise go undramatized.

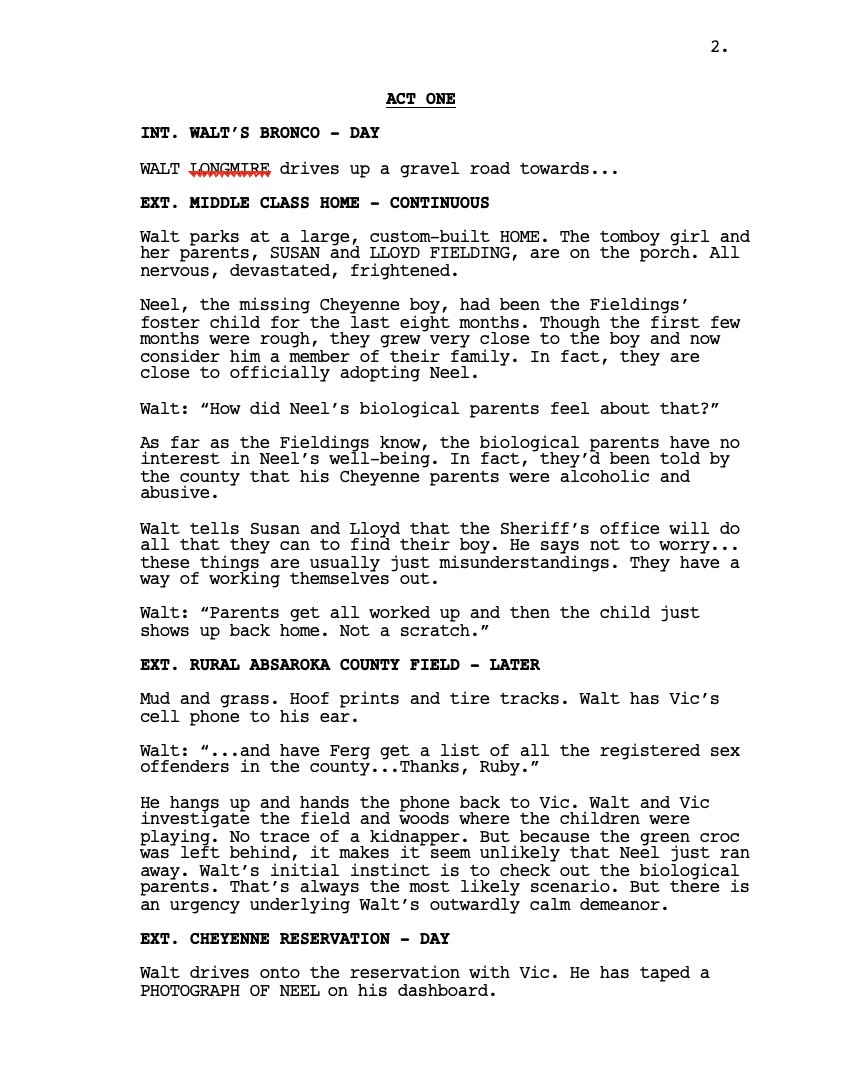

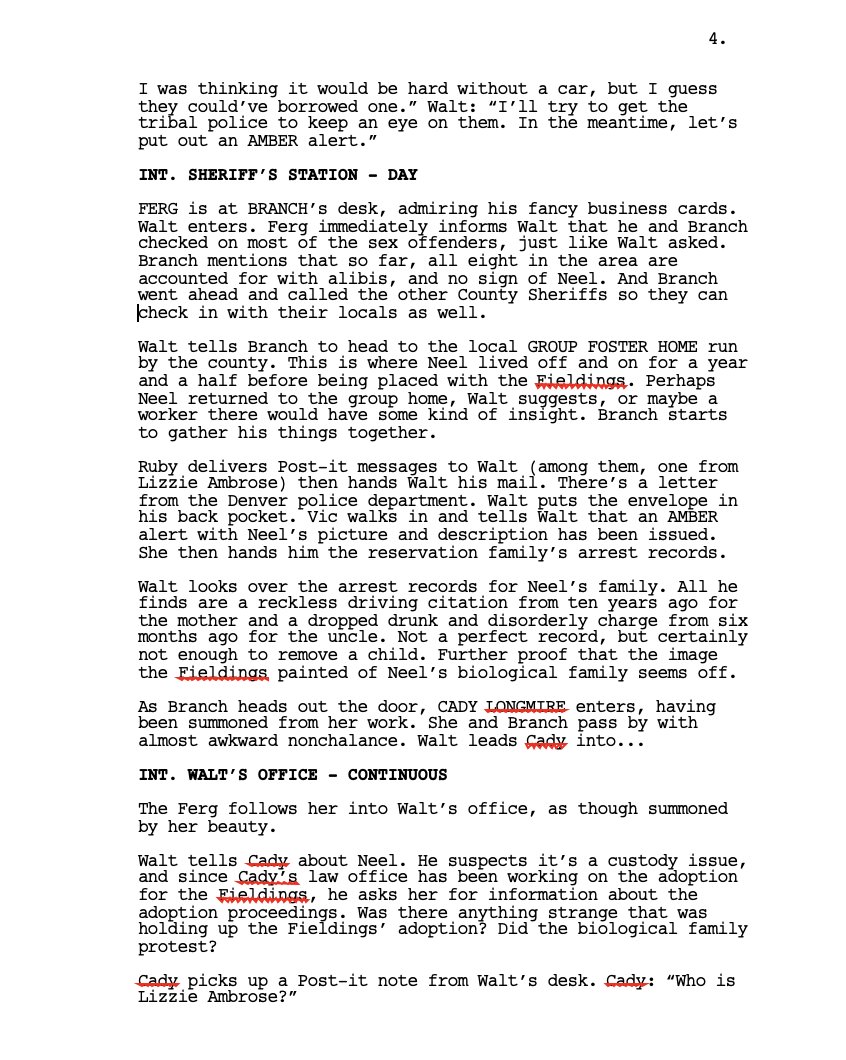

There was no assistant taking notes, so I would do it myself. I'd keep track of the evolving note cards, and add in italics little notes to myself with ideas for details or textures. Here's what my notes from the board looked like:

I flew back to Seattle to start the process of outlining it. By the time I'd returned home, Greer had reached out to my agents: she was quite enthusiastic about how the two weeks had gone, and wanted to explore having me create a country music pilot for her production company.

We didn't end up pursuing the country music show (an idea which came up organically while chatting), I think mostly because I already had three pilot deals and it didn't make sense to have something in fourth position. But, it did give me confidence that I was starting off well.

My first document to turn in for my "Dog Soldier" episode was a summary for the studio/network: the dramatic situation of the ep, how it unfolded (without giving away the end), & why it mattered. Good practice for distilling the drama of an episode to its essence.

After that, the next step was outlining. On LONGMIRE, the outlines were much, much more detailed than yr usual. Nearly scripts in prose form, 30+ pages in length. Here, you work out the structure of each scene with the occasional key line of dialogue. Opening pages, for example:

Greer's philosophy, as I recall: these hyper-detailed outlines are a chance to solve hidden problems with the story, and to also give the studio/network a very full picture of the episode: if they have major notes, it's better to get them earlier in the process.

The basic process on LONGMIRE: I'd turn in my outline. Baldwin and Coveny would read it and write down notes, then pass their notes to Greer. Greer would then do a very, very thorough notes session with me. It would often take hours. Rinse and repeat.

Mostly, we would talk about finding the right shape for each scene. Mostly about structuring correctly for a mystery investigation. How to schedule out the information in a scene. In a way, there would often be two scenes going on at the same time.

The 1st upper level of the scene is the drama of Walt trying to solve the mystery. There needs to be some kind of resistance he has to overcome. And then the scene progresses until he gets the key piece of info he's seeking, or something sends him to the next scene.

This level would provide the dramatic structure of each scene (a lesson that carries over to non-procedural scripts very well, I think). But per many good mystery shows, the true answer to the mystery usually lurks under the questions that *don't* get asked in these scenes.

So there would also often have to be a 2nd mystery-based scene lurking under the Walt-drama. Some detail or piece of evidence or shred of dialogue that -- later in the episode -- Walt would realize was the key to the puzzle all along.

The tricky thing is to have that latent piece of the puzzle be legible to the viewer so they can remember it and go "ah ha!" when it comes back. But to not have it register as a piece of the puzzle at the time it does become legible. To have it be felt without ringing any bells.

That's tricky, and there's no one way to do it. But to tell a mystery story, you have to learn how. It's a specific skill. Greer was very, very patient in walking me through the revision process: usually 2-3 rounds of notes on the outline, then the same on the script.

Her attitude: if the show was going to go multiple seasons, it's better for the long run to teach and train me in-depth right away about how to structure LONGMIRE scenes and scripts so that in future seasons the EPs won't have to carry so much weight.

Even with Greer's massive help, there were some things I struggled with during my first season. For instance: when I went off to write the script for 105, I got overly fixated on proper police procedure.

For 105, I had Walt and his deputy Vic interview foster parents separately in different scenes, since that was the preferred strategy I gathered from my research. This meant that a 1.5 page dramatic scene would stretch out into 4 pages of just info gathering.

It was proper police procedure, but also boring and slow and undramatic as hell. But I couldn't quite see that on my own. I thought I was going to outsmart all the genre-tropes, David Simon style.

This happened a couple of times in my first LONGMIRE script and Greer and the other EPs basically had to restructure and rewrite act one of "Dog Soldier"--lots of my details and dialogue were in the final product, but I had the shape all wrong, even after the notes sessions.

Thankfully, the scenes I wrote from Act Two onward had sturdier shape & largely held. The mystery we hatched was strong, resulting in a strong scene between Walt & a social worker that ended up being among a lot of folks' favorite scenes from the show:

That "Dog Soldier" scene plays out pretty much as I'd scripted it, w/ a couple of lines added by the EPs. I felt great with how it played, especially w/ how Robert Taylor played Walt's big scene, & how director Alex Graves (who I'd hire years later for DAMNATION) handled it all.

The closing montage largely followed my script, tho the final great image of Nighthorse as the Dog Soldier came from the EPs. And the "Sail" song was found in post (I'd suggested Johnny Cash's "Further On Up the Road"). Their song fit much better.

So far, so good. On to the next episode. One difficulty: I was assigned episodes 105 and 107, which pretty much were back-to-back during the heat of production. So while outlining 105, I was also breaking 107. And while I was scripting 105, I was outlining 107.

For a beginning writer, I found it pretty overwhelming. But I mostly kept up. But when the time arrived for going to script on 107, there was almost zero time. So the EPs took my 30 page detailed outline and wrote out the script for episode 107 (called "8 Seconds") from it.

I was credited as sole writer, which was good & honorable (& welcomed by my bank account). The EPs reassured me that it wasn't a reflection of my outline or abilities or standing with them. They just simply didn't have time to go through the notes-and-revisions process with me.

I believed them. But I also couldn't help but get a little paranoid. If they *didn't* think I was up to snuff, wouldn't they have done and said the same thing? Had I gone too far off the path in the opening acts of "Dog Soldier"? Was my "8 Seconds" outline that weak?

I was still in Seattle and they were mostly in Santa Fe filming at this point. So I didn't have the assurance of just daily interaction to quell my anxieties. And they were so busy that communication b/w us basically ended after they'd taken over the script. I got more paranoid.

So yeah, I'd broken in. But at the end of my work on two episodes, I had no idea if LONGMIRE would come back. And I had no idea if I'd be invited back if the show *did* get renewed. Maybe my career would end as suddenly as it started. And I quit a professor job for this.

Plus, I wasn't totally thrilled with how "8 Seconds" turned out. It felt less mine, of course. But I also was starting to realize that I did my best writing during the revision process: once I understood the proper shape and aim of each scene, I could really elevate my writing.

Later, I'd hear from Greer that my ability to take notes and elevate them was one of the reasons they stuck with me through these early times. Some writers, she said, would just repeat back whatever notes they were given, like stenographers.

Greer liked that I'd address and incorporate the notes they gave, but that I'd also often find new interesting textures and colors and sometimes write new surprising-but-fitting dialogue once I had a better grasp of how each scene would work.

I didn't get a chance to do this on "8 Seconds," so that episode always felt a bit flat and rough to me, kind of like a rough draft that got filmed. It was a little bit of a deflating note to end my first season of TV writing. And I had no idea what would come out of it.

At the same time as all of this, I also had two non-TANGLE EYE pilots in development. I was working on these concurrently with LONGMIRE. One was adapting a series of Scandinavian crime novels into a procedural-like crime show. I called it HIVE.

The show as I conceived it focused on an old school Bay Area cop who joins an unconventional crime unit that handles cases the normal cops can't handle. I think my main motivation was that it'd be a way to update the David Milchian troubled cop archetype.

Basically, I was taking a Siepowicz type of alcoholic, loner anti-hero cop (almost a parody of one) and putting him in a hyper-contemporary fictional organization influenced by Deleuze & Guattari and open-source, anti-capitalist, activist philosophies.

I really enjoyed developing HIVE with the producers, who were smart, collaborative, & patient regarding my inexperience. Also, I had some interesting novels to draw from in terms of plots and characters, but I also felt free to change things to fit my own interests at the time.

Intellectually, there was a meta-element I liked: by forcing this Siepowicz character to gradually grow out of his loner alcoholic archetype over the course of the series, I would also be pushing this kind of macho cop storytelling to outgrow those same trope-y limitations. Fun!

After we had a pitch we liked, the producers found some experienced showrunners for us to meet with and we found one that we gelled pretty well with. We started pitching HIVE to networks.

It's now a show I would pursue right now -- my interests have veered elsewhere. But I can see why I was excited: under the cover of an accessible procedural, I could have Trojan Horse'd a whole bunch of subversive shit about masculinity, capitalism, hierarchies, policing, etc.

But then complications ensued. There were some underlying issues with the rights. I don't recall the details at all. But things stalled, and eventually all the parties moved on. Just like that, the project was done just as it was picking up steam.

Once again, I don't think I could go back and "fix" this outcome. Sometimes things just don't work out and aren't in your control. It was a bummer to have months of work seemingly vanish, but the experience of working through season- and series-length arcs was invaluable.

I'd had three pilot deals coming out of my LA trip. This was the second pilot to sort of fade away. And without getting me paid. After a fairy tale start, I was getting a taste of reality.

During this, I was also working on a 3rd pilot for a 3rd studio. The show was the loose brainchild of an interesting character actor with leading man potential. It would be set in Texas & focus on a down-on-his-luck former football star who becomes a fixer for the Dallas elite.

I'd call it a mix between, say, NORTH DALLAS FORTY, MICHAEL CLAYTON, and maybe Joe Don Baker's character from CHARLEY VARRICK. A milieu I liked, especially as it concerned a blue collar dude navigating and outsmarting the moneyed Dallas elite. I love that shit.

Even still, this project was more of a struggle for me than the other projects at the start of my career. I think because I didn't have the experience or the acumen to navigate the different points of view from the various participants.

The actor had the initial idea. Mostly, it just concerned the kind of character he wanted to play, and the setting. I dug these ideas. And I liked him. But then there was everything else: the other characters, the tone, the stories, the themes.

I was a bit at a loss at how to fill out the entirety of the storytelling canvas. I wasn't even really sure what my role was: was I to write something deeply felt that resonated with me, and then hope it resonated with the actor and the producers?

Or was I to figure out ahead of time what they wanted and then try to give that to them? At one point, I was at such a loss that I created a multiple-choice menu of characterization options for supporting characters.

Sorta like: Should the socialite love interest: a) gone to Harvard Business School, or b) written an eating disorder memoir, or c) be obsessed with theology. Etc. Thankfully, I never sent it. But it shows how lost I was on this project.

Usually, my characters & stories groow from my obsessions & interests. Here, I was trying to graft them onto someone's idea while making the producers happy at each step while also trying to figure out how to generate enough creative ownership to actually do interesting work.

Looking back, there were two big difficulties: 1) my inexperience and uncertainty, 2) general creative chaos. Not a terrific pairing for productive script development.

I was brought into the project by a smart younger dude who worked for a father-son producing team. I never met the father, who has a pretty big profile. The son half of the producing team was a big picture guy: "we should do a show about, say, surf punks."

A good idea. But what he doesn't do is get into specifics. Or really communicate a vision. Which I think works if the writer has a strong vision or voice. I think I was too uncertain of my role, & too inexperienced, to be the sort of writer who thrives in this sort of dynamic.

We'd pitched this show to the studio head (father-son had a first look deal) during my 1st week in LA. Minutes before the pitch, we were literally bent over my laptop on the sidewalk outside the building, radically rewriting the pitch. I'm not sure the son had read it until then.

Still, it sold in the room, but mostly I think due to the father-son producing track record and the potential of the actor. The idea was mostly: this cool dude in Dallas gets in over his head with the super rich but comes out on top. It wasn't much more worked out than that.

After we sold the pitch, I went to Dallas for 48 hours with the actor. I met with mobsters and billionaires. I went on ride alongs with cops and stayed up late at night clubs. I watched a Mavs game and downed shots with some Dallas Cowboys. It was as awesome as it sounds.

I got some good material out of the trip. But I was still struggling with my vision of the show, I think largely because I was still approaching the script like a short order cook -- taking requests -- and everyone at the table was requesting a different kind of meal.

My approach was self-defeating. But the chaos on the producer side was equally self-defeating. For a year, I never had a creative conversation where more than one person on the producing side was on the phone with me.

So, sometimes the son would chime in, then the smart young guy who worked for him, then the actor, then the dad. And they all had different visions of the show. And were not aware of the directions the other people were giving. Chaos.

I wrote a script anyway. I turned it over. The son, though full of bluster and seeming confidence, was ultimately very deferential to his father. So I wouldn't know how the script landed until the father read it.

A few days later, I got a message from the son: the father read the first ten pages and absolutely loves it. Great! I waited a few more days. I got a second message: the father doesn't like the rest of the script as much as the opening pages. And that was basically it.

I didn't know what to do with that. If this was me now, I'd arrange things so everyone who had a voice in the project would all have to get on the same call. Partially so there'd be a consensus as to the next direction, but also so they'd have to hear each others' POVs.

But I didn't know how to do that back then. Or that I needed to. So, I did probably the worst thing I could've done: I guessed at what they wanted. Even though everyone wanted different things, and even though (most importantly) it was my job to actually have the vision.

So, I kept the opening ten pages and totally rewrote the rest of the script. New story, plenty of new characters, etc etc. This was not what they were wanting. They were wanting the same thing as the first draft, just "better." I still didn't know what that looked like.

At this point, everyone was getting frustrated. The actor emailed me an idea & I tersely wrote back: "Thank you. I'll take it under consideration." Five minutes after sending that email, I got a phone call from the son: the actor was super pissed off. Lots of stuff like that.

This process had dragged on for over a year and I just wanted it to be over. I kept writing and rewriting scripts and outlines, but they never got to the studio, which was getting impatient on their investment (I'd been paid half my script fee at the start).

Finally, the actor stepped up and came up with a very good idea: me and him and the younger exec would meet each day at the actor's house until we hashed out an outline that we felt good about. I was eager for this.

The actor & the junior exec were the two people I liked the most on this project, & felt most creatively aligned with. Also, I figured if 3 of us were in unison, then that would break through the sort of disorganized stalemate that had mired us in development hell for a year.

It took us about 3 days to re-break the pilot. A few things stayed from my working draft, while we also made some cool discoveries. The actor was very strong on individual scenes, but was less strong on a bird's-eye view for setting up a series. But I was pretty good at that.

I went off and wrote the script with the new outline. A few notes, then it got passed to the studio, which had notes and seemed pretty happy with it. I won't post it here, as it's still technically the property of the studio. But we had some momentum back.

I just read it for the first time in like 9 years. The story is a little sloppy, but the character work & dialogue are pretty interesting. It's a wittier, more banter-heavy script than what I usually write. Light on emotion, but with a nice hang-out vibe. I've done worse.

Anyway, by the time we turned in the script, Showtime had ordered their own fixer show RAY DONOVAN to series, so the studio shelved the project without taking it out, knowing that there wouldn't be a market for another macho fixer show.

Though the process was excruciating at times -- due to myself as much as anyone -- this Texas fixer project was also my first industry paycheck, so I can't help but regard it with some affection. It also taught me some hard lessons about my own limitations.

Coming out of this process, I think I stopped trying to guess what other people wanted, especially at the interview/pitch stage. Because I realized that even if I did get the job, I'd be setting myself up for misery later.

Luckily, right now I have enough security that I don't go into meetings with an "anything to get the job" mindset. Instead, I take meetings for projects that look interesting to me and that I think I have a specific POV on. Then I pitch my specific POV and let things play out.

This has been such a better approach than my earlier short-order-cook guessing one. Also, I now take much more responsibility -- especially in the TV world -- to be the one with the unifying vision. And to communicate and teach that vision, while also letting it evolve.

These first few early pilot projects also taught me that I often produce my best work when I just go off & write the thing, rather than over develop it ahead of time. This usually means foregoing payment up front, but it also often means stronger work and more creative freedom.

Looking back, this Texas fixer project is the one early project that I think I could go back and do a much better job on. I should've started off with a clear vision of what I wanted for the show and done more myself to get the input I needed to do my best work. Lessons learned.

An aside: a turning point for me was when I stopped complaining about bad notes & started taking personal responsibility for the quality of notes I was receiving. That is, actively doing everything I can do to create the working conditions that I feel that I need.

So at the beginning, I had three pilot deals and a gig freelancing two episodes of LONGMIRE. At the end of this first year or so, TANGLE EYE didn't sell, HIVE fell apart, and the Texas fixer show got shelved. Inauspicious.

I still hadn't come up with a good idea for the second part of the two-pilot deal I'd gotten with TANGLE EYE. My experience on LONGMIRE was very positive, though it ended with some paranoia and uncertainty. And I didn't know if the show would even get renewed.

During this time, my wife (who was doing a post-doc in Seattle) got a tenure track professor job in Ann Arbor. So we moved to Michigan with our kids while I tried to remotely keep my new career afloat, now from a more distant location than before.

After a year in the industry, I now had one pilot deal instead of three. And if LONGMIRE ggot canceled, or if I wasn't asked back, I didn't know if any other shows would have any interest in a 36 year old freelancer living in Michigan. I seemed to be going a bit backwards.

If I do another thread, it'll cover coming back for a second shot at LONGMIRE, coming up with the second part of my two-pilot deal and selling that show, and then the ensuing biggest disappointment of my career, which would then lead to probably my most satisfying achievements.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter