FWIW, I’m relatively relaxed about the fiscal costs of #Covid: borrowing will drop sharply as the economy recovers, the #debt burden is manageable, and there’s no need for #austerity to pay for it.

But this isn’t a green light to abandon fiscal responsibility altogether… (1/12)

But this isn’t a green light to abandon fiscal responsibility altogether… (1/12)

For a start, the long-term outlook is more worrying.

The #OBR’s Fiscal Sustainability Report (July) includes scenarios where unchecked increases in public spending on health, adult social care and pensions could see debt balloon to more than 400% of GDP in 2070... (2/12)

The #OBR’s Fiscal Sustainability Report (July) includes scenarios where unchecked increases in public spending on health, adult social care and pensions could see debt balloon to more than 400% of GDP in 2070... (2/12)

In the meantime, even if the government doesn’t face the same financial constraints as a household, high public spending and borrowing still has other costs, including the poor allocation of resources and the risk of runaway #inflation… (3/12)

As even the more sensible proponents of Modern Monetary Theory ( #MMT) recognise, the state’s ability to print money does not mean it can create real resources out of thin air. These constraints will start to bite again when the economy recovers. (4/12)

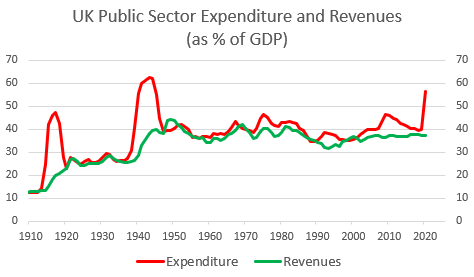

Public sector spending has already averaged around 40% of UK GDP since WWII. In my view, this is already more than enough to fund good public services and a decent welfare safety net. (5/12)

It must be possible to find substantial savings by pulling the state back from activities that can be done at least as well by the private sector - and still have room to increase public investment in the limited number of projects that cannot be left to the markets. (6/12)

This is a very different way of thinking to that of many commentators, who take a certain path for public spending as a given and search instead for ways to raise the tax burden (usually to at least 40% of GDP) to meet it. (7/12)

It is also important not to undermine the independence of the Bank of England. The central bank’s main job is to ‘maintain price stability’. Supporting government policy more generally is a secondary objective. (8/12)

For now, there is no contradiction. The MPC has judged that additional monetary stimulus is required to prevent inflation from becoming too low. Implementing this by using #QE to buy gilts has had the welcome side-effect of keeping government borrowing costs down. (9/12)

This could change. Facilitating a temporary increase in government borrowing during a 1-in-300-years recession is one thing. But subverting monetary policy to underwrite a permanent increase in the size and role of the state would be quite another. (10/12)

Last, but not least, issuing unlimited amounts of debt is likely to drive up interest rates in ways that do threaten debt sustainability. If the government continued to rack up huge debts even in better times, the outcome could be very different. (11/12)

In summary, it is misleading to claim that the UK has already ‘maxed out its credit card’.

But it would be even more misleading to suggest that the government has a ‘blank cheque’ to spend or borrow as much as it likes, whenever it likes. (12/12)

But it would be even more misleading to suggest that the government has a ‘blank cheque’ to spend or borrow as much as it likes, whenever it likes. (12/12)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter