Most of my research is in econometrics but I have been lucky to also work on an amazing interdisciplinary project in economic history. A resulting paper on trade in ancient Greece has just been published in @EJ_RES. Below, I explain its contribution.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa026

1/n

https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueaa026

1/n

The paper, "Landscape Change and Trade in Ancient Greece: Evidence from Pollen Data," is co-authored with A. Izdebski, A. Bonnier ( @AntonMalp), G. Koloch and K. Kouli. We revisit one of the main questions of ancient history: How important were markets and trade in antiquity?

2/n

2/n

Using pollen data from six sites in southern Greece, we study structural changes in Greek agriculture from 1000 BCE to 600 CE. We argue that cash cropping and interregional trade were important for the ancient Greek economy already by the 6th century BCE.

3/n

3/n

But what is pollen data to begin with? When plants pollinate, pollen accumulates in lake and peat sediments. Palynologists extract this information and create what are basically panel datasets for each site. My coauthors and I combine six such datasets to study structural...

4/n

4/n

change at the regional level. Given the modern knowledge of ancient diets, we focus on the relative presence of cereal, olive and vine pollen. (See below a magnified wheat pollen spore; identifying and counting those is a necessary first step in palynological research.)

5/n

5/n

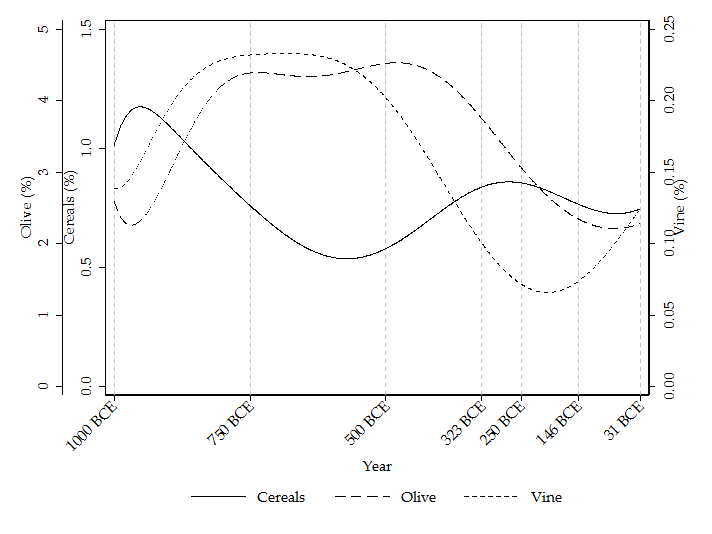

Our main finding is that in the Archaic period (before 480 BCE), which was a time of population growth in S Greece, we observe a decrease in the relative production of cereals and a simultaneous increase in the relative importance of olives and vines. (See figure below.)

6/n

6/n

While we admit that other interpretations are possible, we take this finding as evidence of a trade expansion. We also provide additional supporting evidence for this interpretation. First, we argue that these results are consistent with the timing of the foundation of...

7/n

7/n

the Greek colonies in the Black Sea region, which were perhaps the most likely trade partner of mainland Greece. Second, we use the FAO GAEZ data to establish that S Greece has a comparative advantage in olive cultivation as opposed to cereals. (See figure below.)

8/n

8/n

Third, we perform a simple diff-in-diff exercise to show that there was a differential trend in agricultural production in the late Archaic and Classical periods, which was associated with costs of trade with the Black Sea colonies.

9/n

9/n

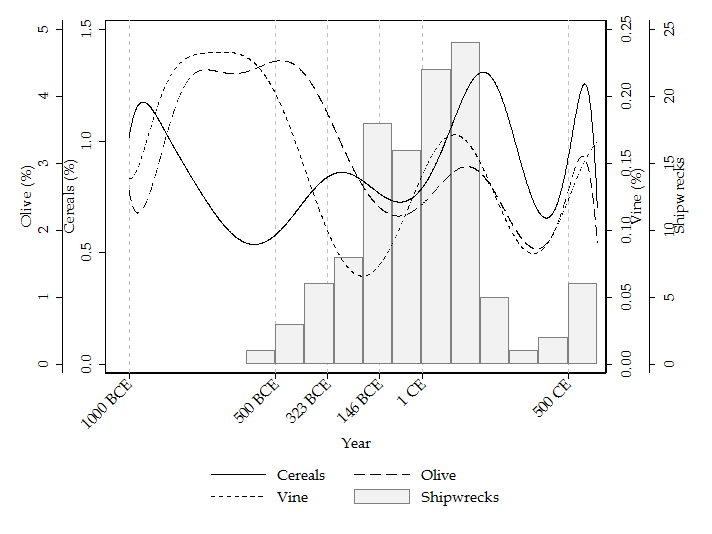

Finally, we also validate our main estimates through a comparison with auxiliary data on settlement dynamics, shipwrecks and ancient oil and wine presses. We show that our estimates are consistent with these sources of data whenever we would expect them to be.

10/n

10/n

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter