As I read the sad news about Debenhams going into liquidation, I was reminded of my research into a 1872 Debenham and Freebody “Fashion Book” a few years ago. So, feeling reflective, I thought I’d share this and some of my thoughts on it.

Debenhams is 242 years old which makes its demise all the more heart-breaking. Founded back in 1778, the nationwide department store developed from a single London-based shop called Debenham and Freebody.

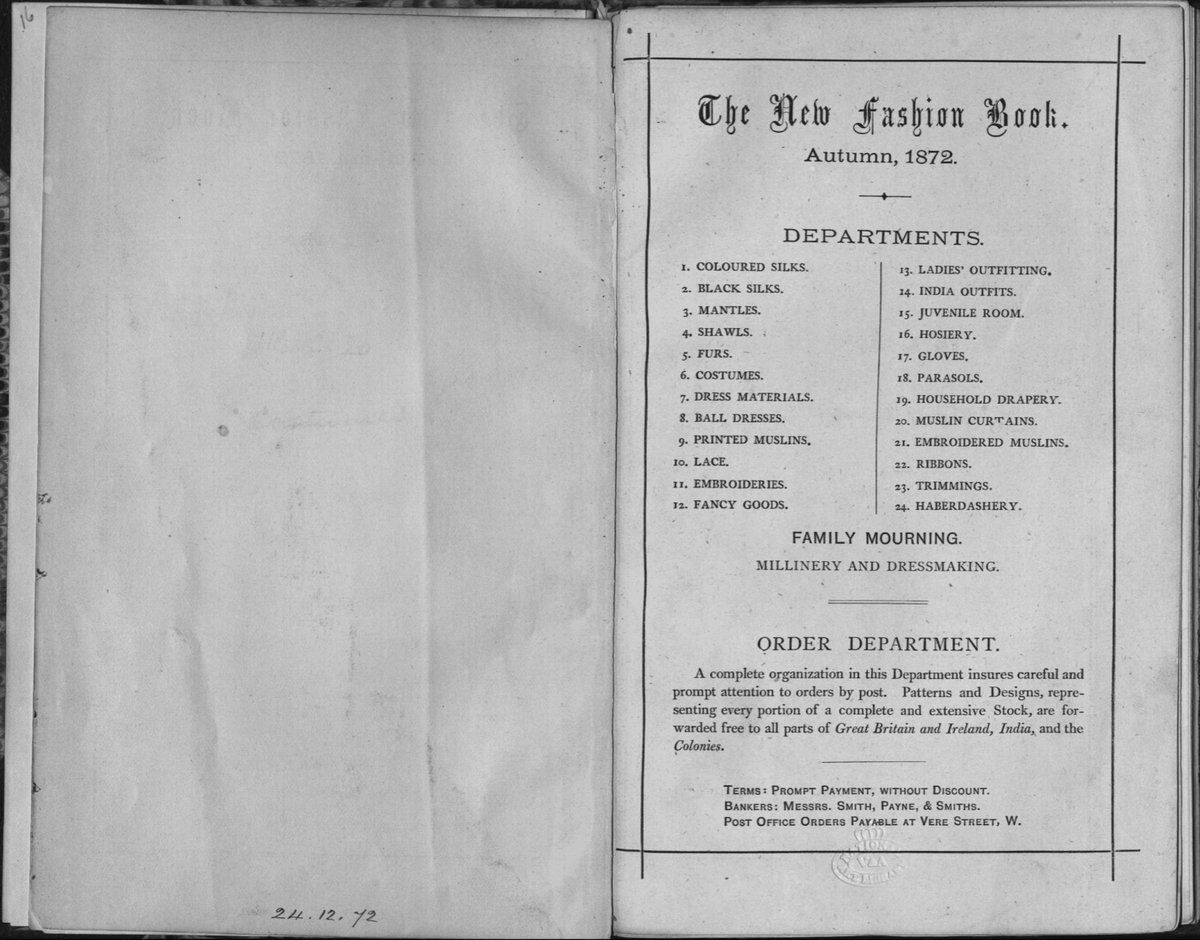

Their 1872 “Fashion Book” was for the attentions of mail order customers, who wished to shop at Debenham and Freebody from the comfort and convenience of their own homes, which could apparently be as far away as New Zealand, with the help of the Post Office!

The etched illustrations and copy give a glimpse into only “a portion” of the goods they sold via various departments, one of which was wonderfully dedicated to parasols alone. Their wares included, but were certainly not limited to: costumes, ball dresses, skirts and mantles.

However, their “Fashion Book” also showcases some of the progressive and, I think, rather fascinating retail services they offered, which are alike those provided by similar traders from this period.

Customers purchasing mourning dress got special attention. “Experienced Dressmakers” would be sent to their homes in “all parts of the country upon receipt of telegram or letter,” presumably to assist with the selection and fitting of their orders - impressive customer service!

Alternatively, customers could still have their garment model (mourning or otherwise) made to their personal measures without the aid of a dressmaker. All they had to do was fill in the included “self-measurement form” and forward this to the dressmaking department.

The "self-measurement form" vaguely requests eleven measurements, from customers’ necks the hems of their skirts. If you’ve ever tried to take your measurements, you’ll understand why I question whether this service would have always resulted in the promised “perfect fit.”

Still, there were chances to prevent or remedy shopping disappointments. Pre-purchase “Patterns and Designs” could be sent all over the world for free. And, to avoid post-purchase regrets, goods could be sent “on approval,” meaning that they could be returned.

Nevertheless, misfit and mistake purchases could surely still arise from such mail order clothing consumption, which makes me wonder if the experience of these nineteenth century postal shoppers is at all comparable to that of the online shopper today.

Perhaps they would be able to relate to the bemusement we feel when the visual representation of a garment, purchased from behind a screen, seems to have got lost in material translation, or even just lost in the post.

So, in some ways, the services advertised to shoppers 148 years in Debenham & Freebody's 1872 “Fashion Book” actually parallel those offered (until recently) by Debenhams today: global home delivery, convenient remote shopping and the option to return unwanted purchases.

Over the past decade, called “the death of the department store” by @nytimes, such services have become e-commerce staples. As retail moves online, where abstract purchases are made from mystifying visual representations, I wonder: are we returning to Victorian modes of shopping?

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter