I've been seeing a lot of people saying the Moderna and Pfizer mRNA vaccines were made in 2 days, and that it will be amazing and perfect for all diseases. Unfortunately, that's not exactly right. Here's a thread on why COVID-19 was the perfect disease for mRNA vaccines.

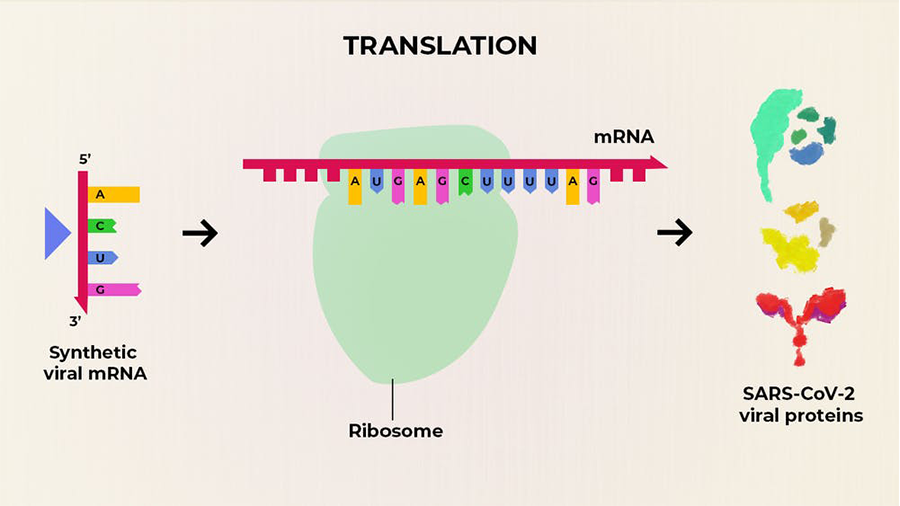

First of all, what's mRNA? Your body stores its genetic code in DNA. But DNA needs to be translated by cells to form proteins. So cells make copies of DNA with mRNA ("messenger" RNA) to go to the protein-making parts of the cell. Learn more here: https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/messenger-rna

This is obviously useful: you can use mRNA to turn cells into manufacturing facilities. The problem is that your body can very easily detect foreign mRNA. In the 1980s-2000s a new method called pseudo-mRNA was invented. That's the technology the new vaccines are made of.

Your body creates immunity in response to exposure to a foreign body. So the way mRNA works for a vaccine is simple: get your cells to create proteins that generate immunity. Then, you generate an immune response to the proteins *your own body created*. It's unbelievably cool.

So how did Moderna create the first vaccine so quickly? In 2 days, famously? The first viral genome was posted January 10, 2020. They downloaded the genome, analyzed it for 2 days, and then had their candidate. From there, it's just testing. https://virological.org/t/novel-2019-coronavirus-genome/319

Seems easy, right? Not so fast. Moderna's vaccine, MRNA 1273, doesn't just have your cells make whole SARS-CoV-2 viruses. That would just mean that you get infected! Instead, it just encodes the spike protein. That generates the immune response without getting you sick.

This is super promising. The main way you'd get vaccinated in the past is an "inactivated virus" which is basically dead or severely weakened. This should be less risky and easier to manufacture. But it won't always be this easy. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41541-020-0159-8

To get here, you have to know which proteins matter and which genes encode those proteins. With COVID-19, this was easy because SARS-CoV-2 has an 89% similarity score with SARS. The main difference is the spike protein. So it wasn't hard to isolate which protein we cared about.

The other problem is mutations. SARS-CoV-2 hardly mutates at all; only 2 mutations per month. So the genome was quite stable, meaning that vaccine designers could rely on the genomes they got for longer. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02544-6

Even SARS-CoV-2 has accumulated a large family tree over less than a year of existence. You can see the phylogenic tree here. It's quite a lot!

https://nextstrain.org/ncov/global

https://nextstrain.org/ncov/global

Combine these factors--infection complexity and mutation rates--and you can see how most diseases will be tougher to make vaccines for. In fact, Moderna has been working on vaccines for HIV and Zika since 2016 with only some progress. https://www.modernatx.com/about-us/modernas-key-milestones-and-advancements

Plus, mRNA is not so stable, which means that it has a somewhat complex supply chain. I think this will ultimately be resolved by innovation in delivery and improvements in cold chains as demand goes up with mRNA vaccine successes. But this is a current key limitation.

My point is not that mRNA vaccines aren't revolutionary (they are) nor that we won't use them for many vaccines in the future (we will). It's that mRNA vaccines aren't a magic bullet. COVID-19 was the perfect test case for showing mRNA's power. It just won't always be this easy.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter