Nsowakwet, also known as Chief John Young, was leader of a band of Potawatomi that lived in Central Wisconsin from 1880-1910. Their settlement was located in the southeast corner of the township of Cleveland, Marathon County, just 2 miles from my childhood home.

Nsowakwet was born in Illinois around the time of the second Treaty of Chicago, when the land between Lake Michigan and Lake Winnebago was ceded to the US government. Many Potawatomi were removed west of the Mississippi to Kansas on the Trail of Death, and some went voluntarily.

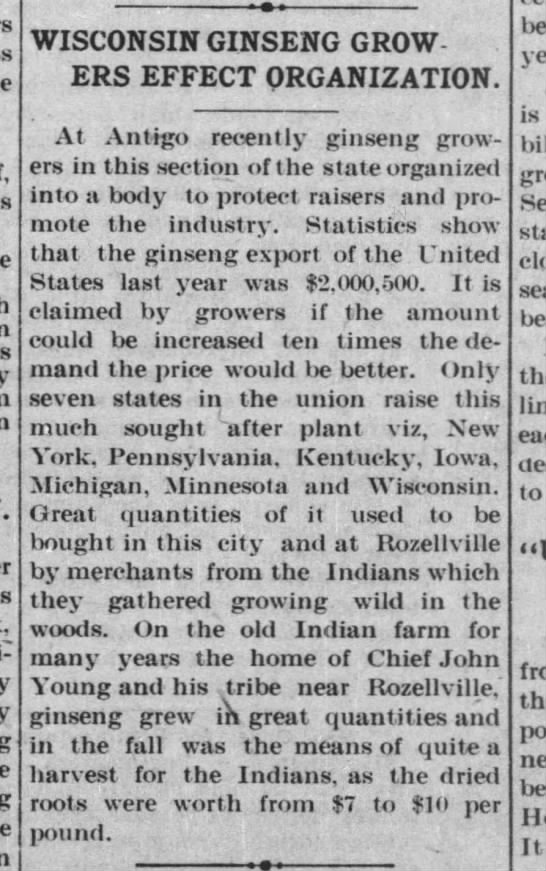

Some refused to go and chose to make their homes in the forests of central and northern Wisconsin, where they could live freely. In fact, the origins of the ginseng industry lie with Native peoples, who harvested and sold wild ginseng, slippery elm, and sap from sugar maples.

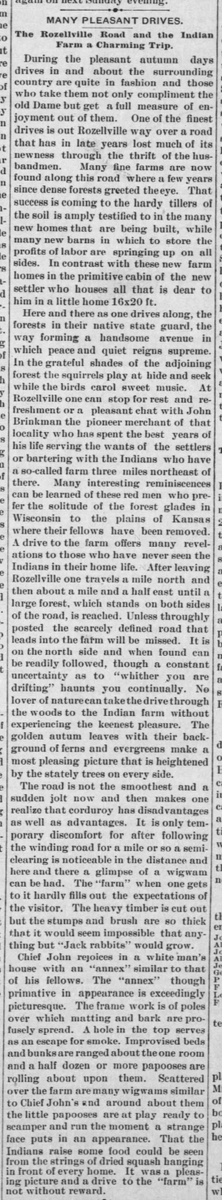

Nsowakwet wasn't alone in his preference for the woods. 1895 Wisconsin census records show 150 non-white people living in the township of Day. Large gatherings were often held there, sometimes numbering in the hundreds.

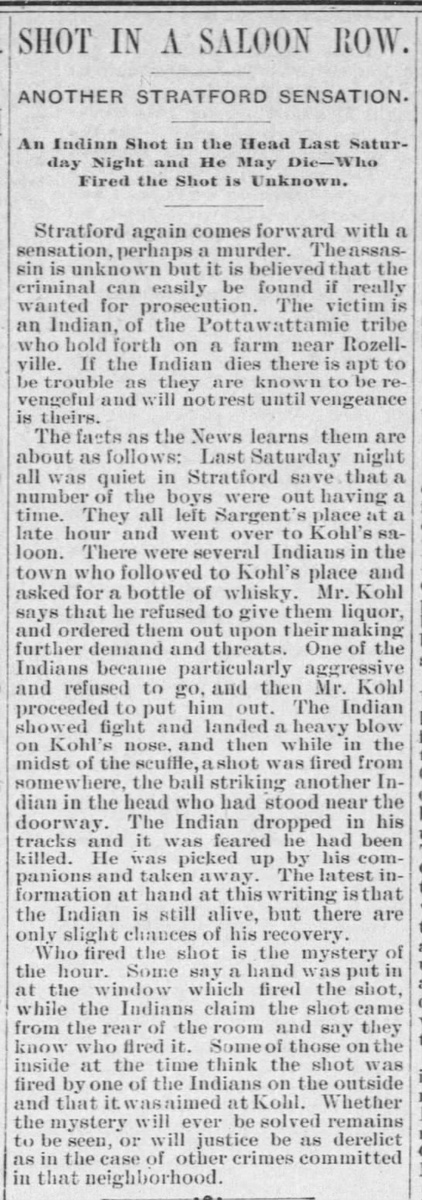

Laws prohibiting the sale of alcohol to Native peoples had been in place since the early 1800s, and reinforced in 1832, based on the false idea that Native people were more violent than whites when drunk. This idea has been completely discredited.

It's worth noting that saloons were hotbeds of violence during the lumbering era, and Stratford notched a reputation in the early 1890s as a particularly lawless locale.

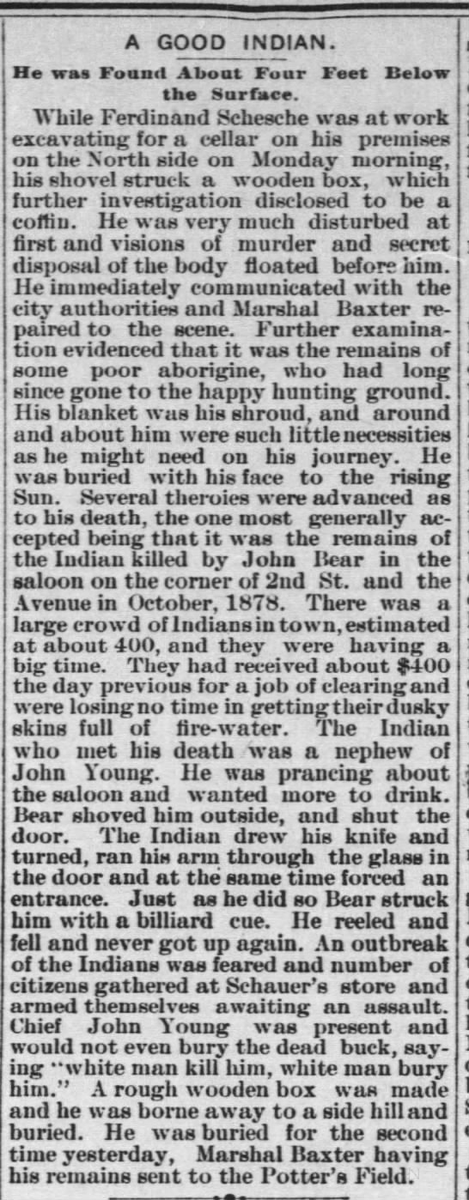

Two saloon murders of Potawatomi men are reported in the Marshfield newspaper during the time of Nsowakwet's sojourn. One occurred in 1878 in Marshfield, on the corner of 2nd Street and Central Avenue.

The victim was Nsowakwet's nephew. Nsowakwet is reported to have said, "White man kill him, white man bury him." He was buried on a hill on the north side of Marshfield and his coffin was uncovered by chance in 1891 by a man doing excavations for a cellar.

The second incident occurred in 1893, at Kohl's saloon near Stratford. A Potawatomi man was shot during a brawl but his shooter was never found or brought to justice. Local newspapers worried that revenge was coming, but nothing was ever reported.

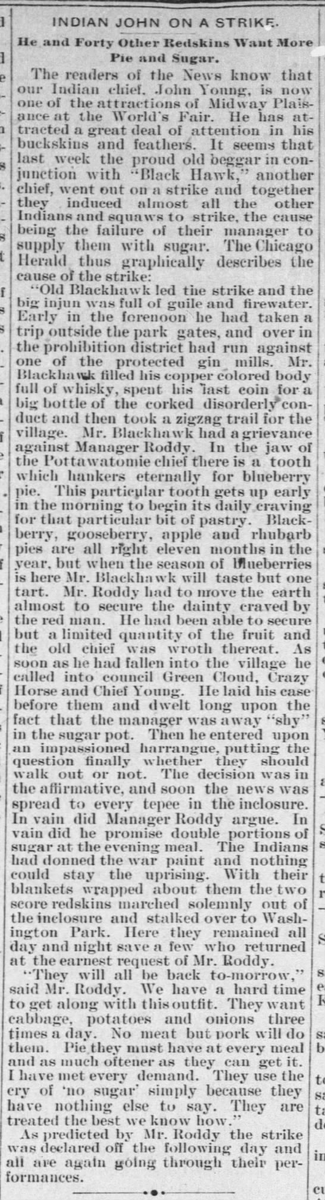

Nsowakwet was a well-known practitioner of the Drum Dance. Nsowakwet and other tribal members were part of a delegation of Native performers who spent the summer of 1893 at the Chicago World's Fair.

Nsowakwet was the son of Chief John Young, the Potawatomi leader much mentioned in reports of the fair for his claim that his father had named Chicago. Local papers report that the Potawatomi attempted to strike for more sugar but were unsuccessful.

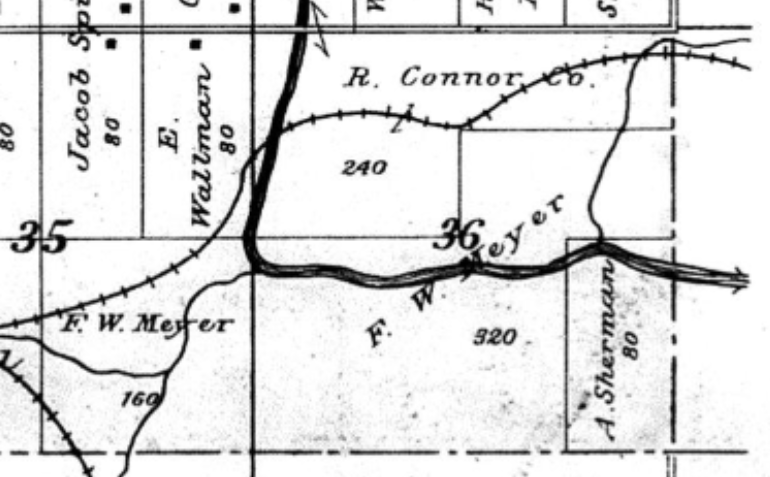

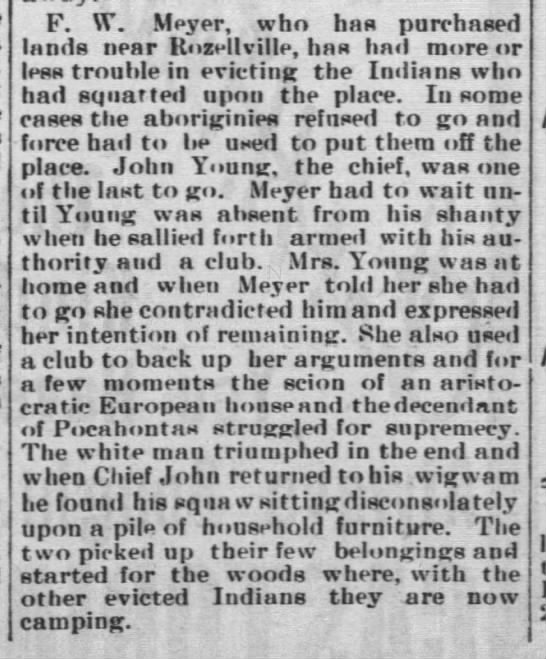

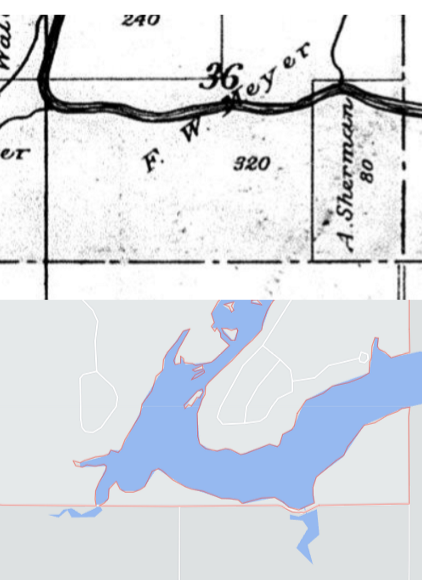

In 1898, the land in the southeast corner of the township of Cleveland was sold to F.W. Meyer, who forcibly evicted Nsowakwet and his band from their long time home on the picturesque banks of the Big Eau Pleine River.

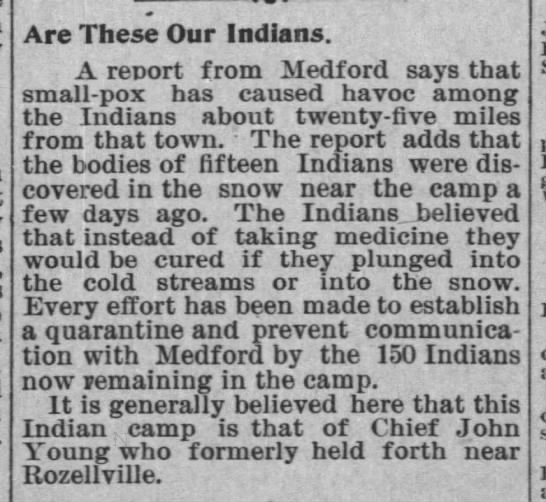

The band scattered, some to Skunk Hill (or Powers Bluff, about 20 miles to the south), and some, including Nsowakwet, to a remote clearing west of Medford, called Big Indian Farms. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Big_Indian_Farms

Their new home was not without tragedy. The small community was devastated by smallpox in the winter of 1900-1901. It is said that 60 people died of the disease.

Chief John's band of Potawatomi is mentioned in the Marshfield paper again in 1904, this time when Bill Sky, a member of the tribe who was intoxicated was hit by a train in Unity in gruesome fashion after apparently falling asleep on the railroad.

Around 1908, Nsowakwet's band left Taylor County and moved to McCord, Wisconsin, where they became part of the group we know today as the Forest County Potawatomi.

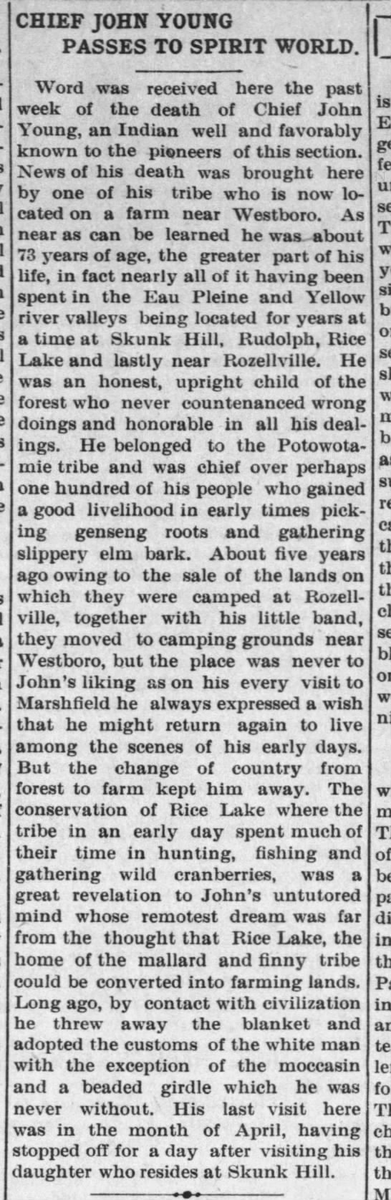

In 1910, Nsowakwet passed away and was buried there. His obituary says that he never found his new home to his liking, and always longed to return to the familiar haunts of central Wisconsin.

Stories of Chief John Young continued long after his death, with one of the most thorough examinations appearing in a Sheboygan newspaper in 1932, including this iconic image.

By the time I lived a few miles from the Indian farm in Rozellville in the 1990s, no one ever spoke of Nsowakwet or his settlement, and I grew up under the mistaken impression that no indigenous people had ever lived in Stratford.

In comparing maps from 1881, 1901, and the present, it's likely that most remnants of the village were completely flooded by the building of the dam at Moon and the creation of the Big Eau Pleine Reservoir in 1936.

There's so much more that could be said about the settlement at Skunk Hill (Powers Bluff) or the generations of Native history of Rice Lake (now in the Mead Wildlife Area). More research could be done into the experience of an Indigenous person at the World's Fair in Chicago.

As the descendants of settlers, it's important to realize that the land we are standing on transcends this moment, and to view the present in light of the past. In today's society, it's easy to miss that connection to the place where we live.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter