Aspirin continues to be the most widely used anti-platelet agent, 125 years after its synthesis. But where did it come from - and why do we give it in such weird doses (e.g. 81, 162 & 325 mg) – at least in the United States? #HematologyTweetstory 35 will answer these questions./1

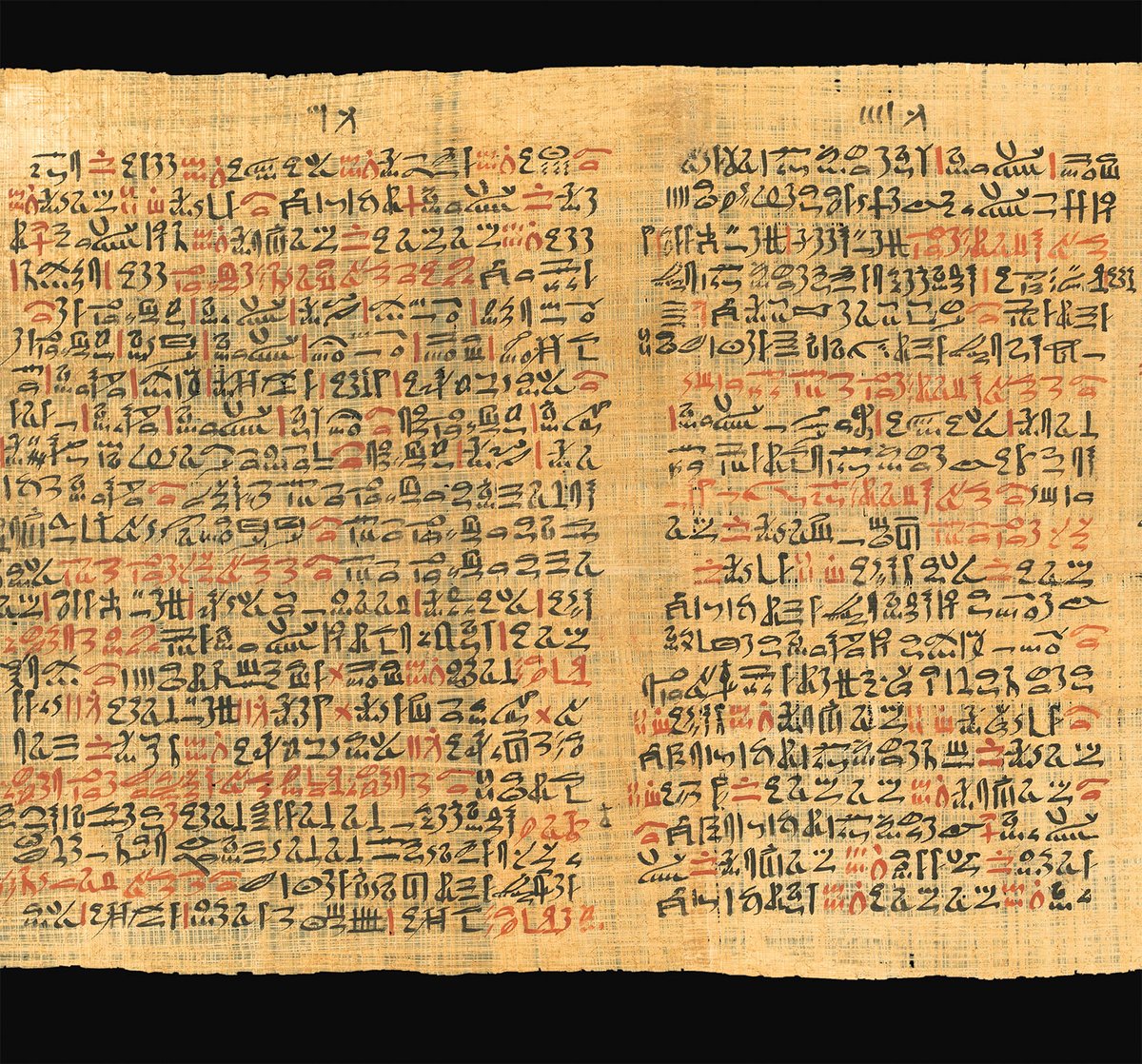

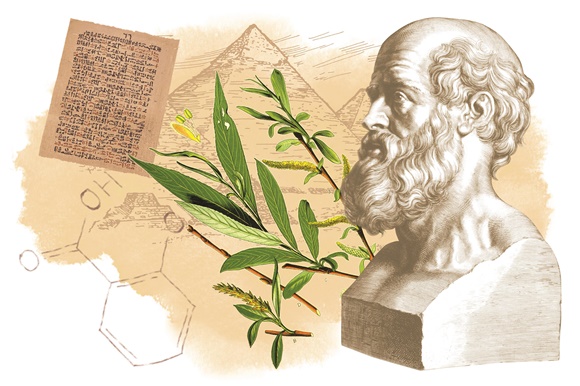

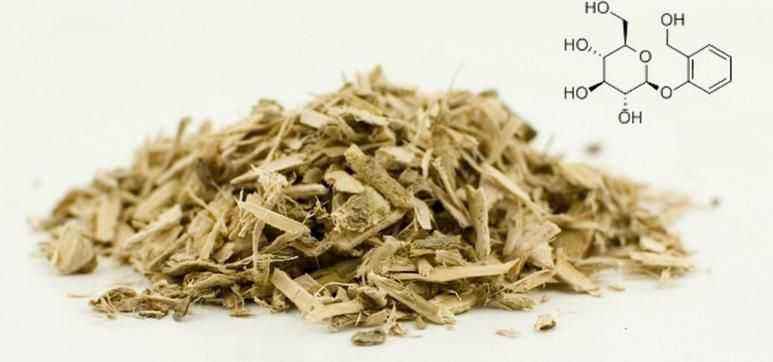

Some lucky ancient person serendipitously discovered that willow bark & leaves relieved pain. Hippocrates used tea made from willow leaf to ease childbirth, while the Egyptian Ebers papyrus (~1500 BCE) mentions willow for aches and pains. (Images: Sermo/Pharmaceutical Journal)/2

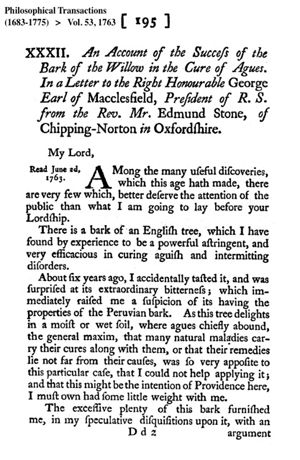

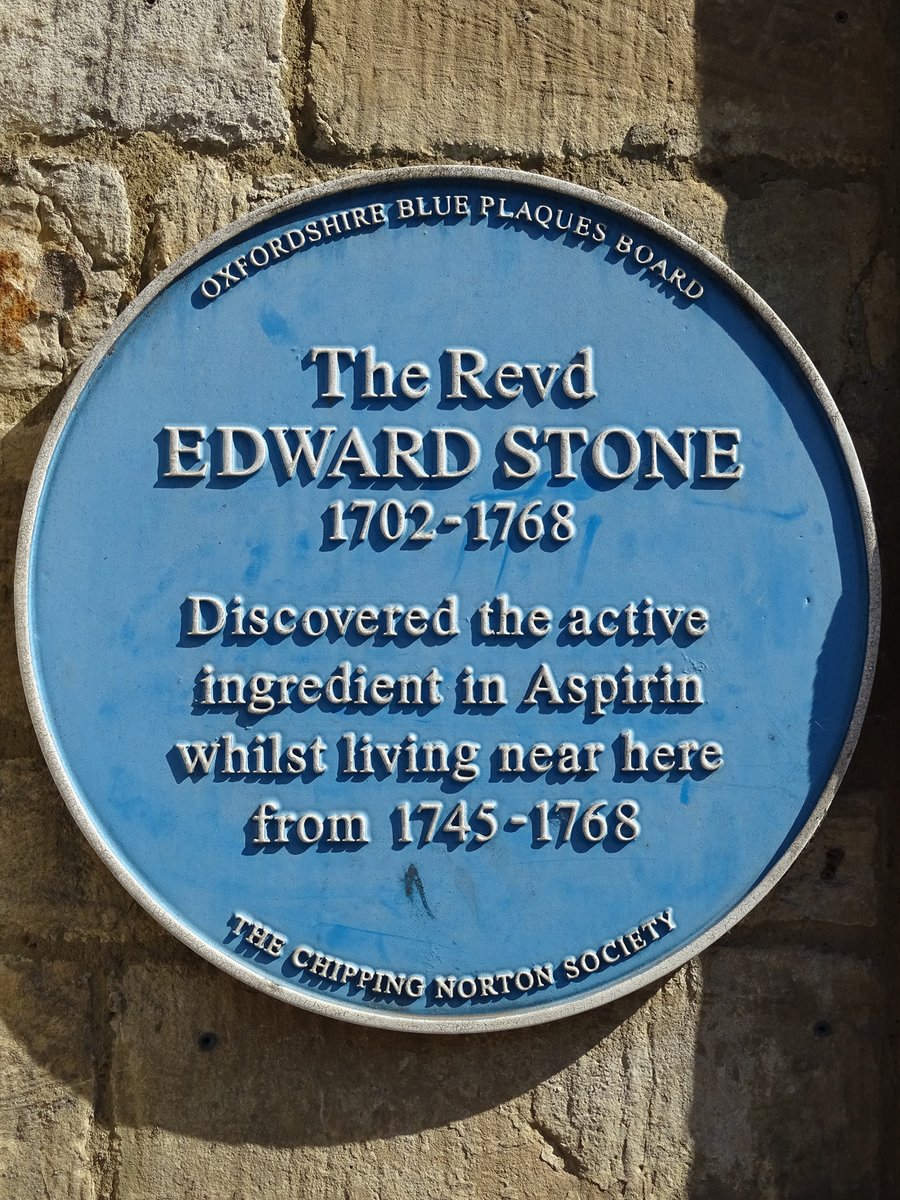

In 1763, @royalsociety published a study of dried willow bark for rheumatism, submitted by Edward Stone (1702-1768), a vicar from Chipping Norton in the Cotswolds & fellow @WadhamOxford. Back then a lot of “natural philosophy” (early science) was done by Anglican clergy./ 3

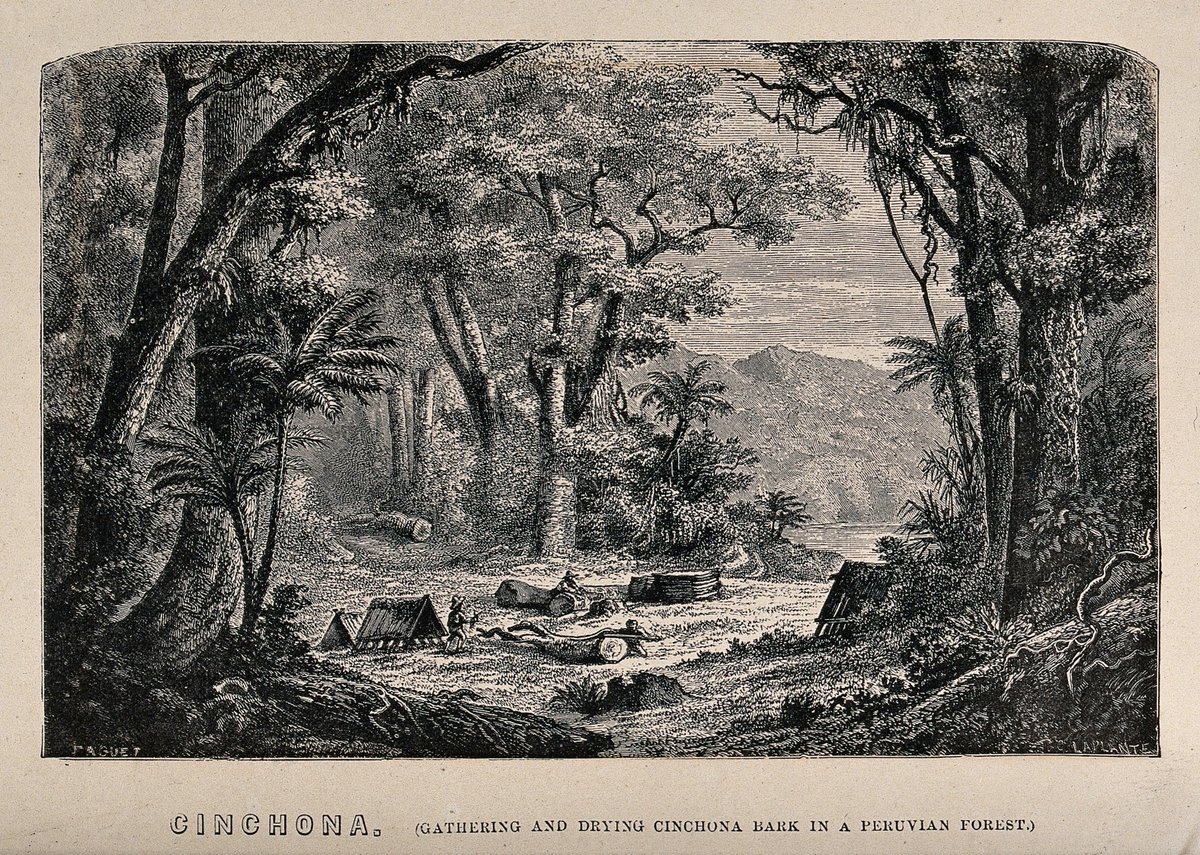

Stone knew that the bark of the famous Peruvian cinchona “fever tree” tastes bitter - yet quinine, used to treat the fevers of “ague” (malaria), is derived from it. Since willow bark has a similar bitter taste, he decided to study willow to see if it was useful for fevers, too./4

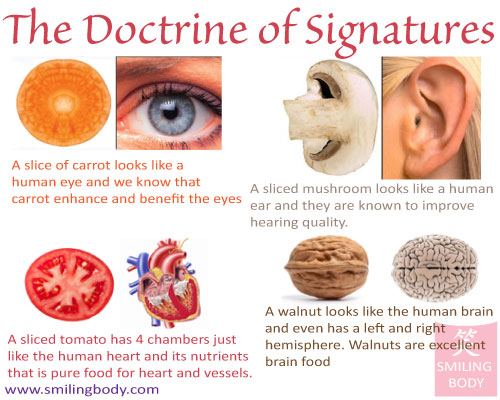

Stone was a believer in Galenic “Doctrine of Signatures”: the shape of a plant offers clue to its medicine use. As botanist William Coles (1626–1662) wrote, “God made 'Herbes for the use of men, and hath given them particular Signatures, whereby a man may read the use of them.”/5

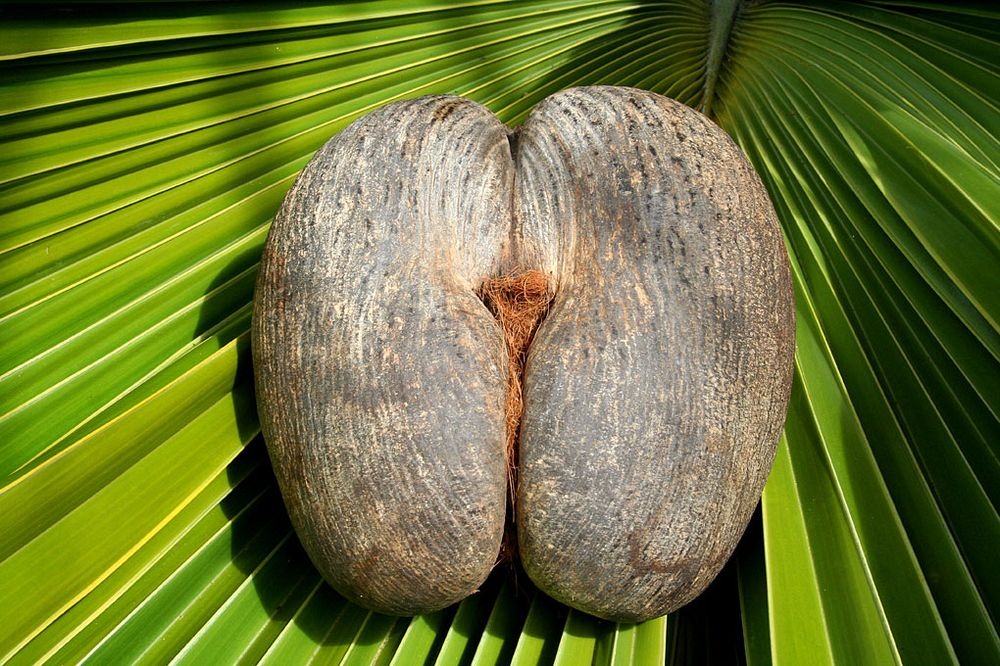

So brain-like walnuts were used for headaches, lungwort for lung ailments, etc. Some people with poor critical thinking skills still believe this in 2020. I wonder what they think is the best use of the Stinkhorn mushroom - or the famous seed of the Coco de mer palm?  /6

/6

/6

/6

Stone wrote about the willow, “This tree delights in a moist or wet soil, where agues chiefly abound. Many natural maladies carry their cures along with them or... their remedies lie not far from their causes... I could not help applying.” Poor reasoning, but a lucky outcome./7

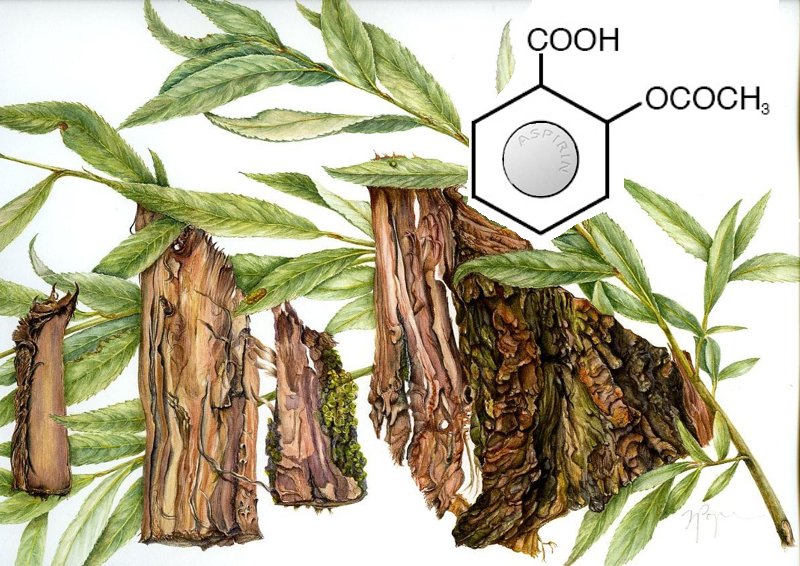

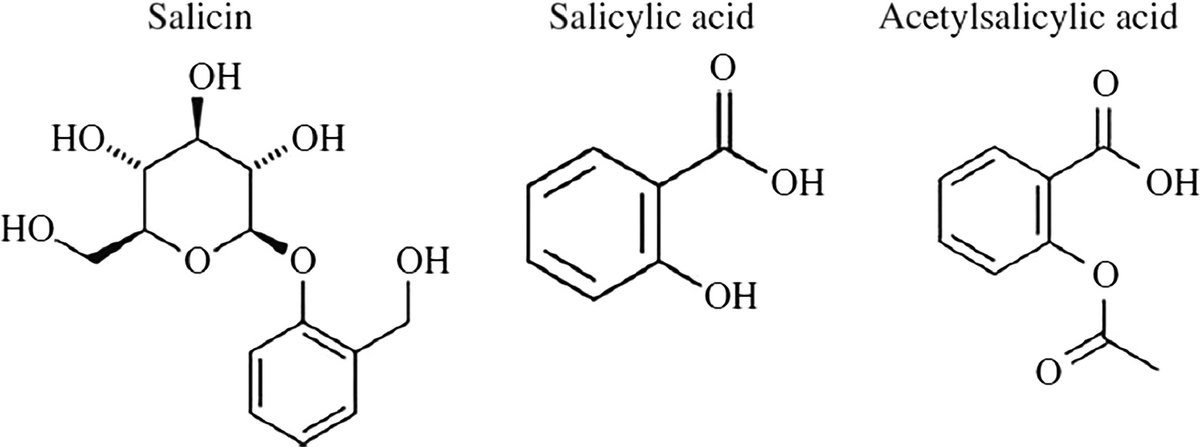

In 1828, a pharmacist in Munich, Johann Andreas Buchner (1783-1852), purified the active ingredient from willow. Buchner had a special interest in plant alkaloids. He named the bitter-tasting crystals “salicin”; the genus of willow is Salix. (Images: Stanford Chemical.)/8

Then, in 1838, an Sicilian chemist named Raffaele Piria (1814–1865) produced a stronger compound from the willow bark crystals. He called it "salicylic acid". (Salicylic acid and salicin image: Desborough & Keeling, BrJHaem 2017)/9

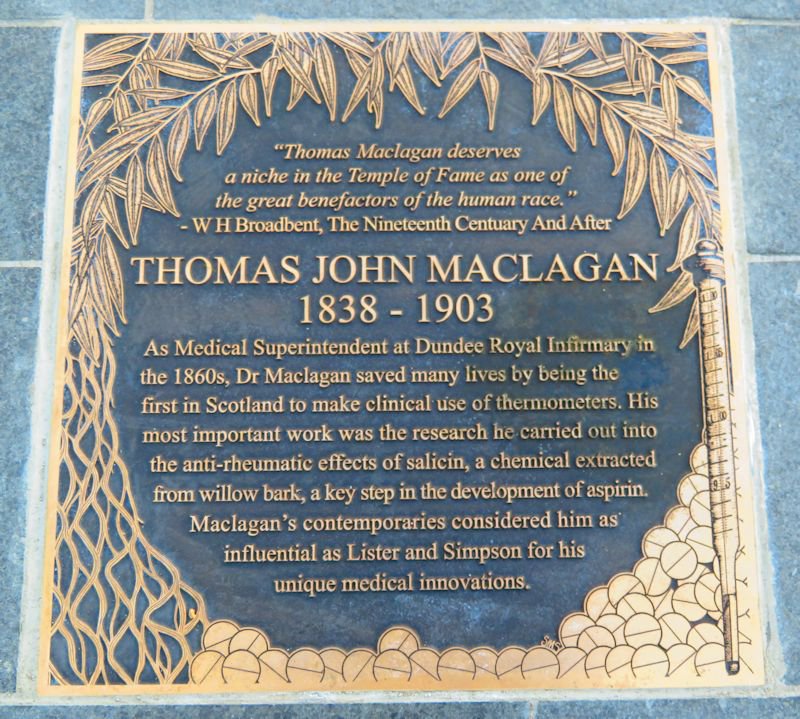

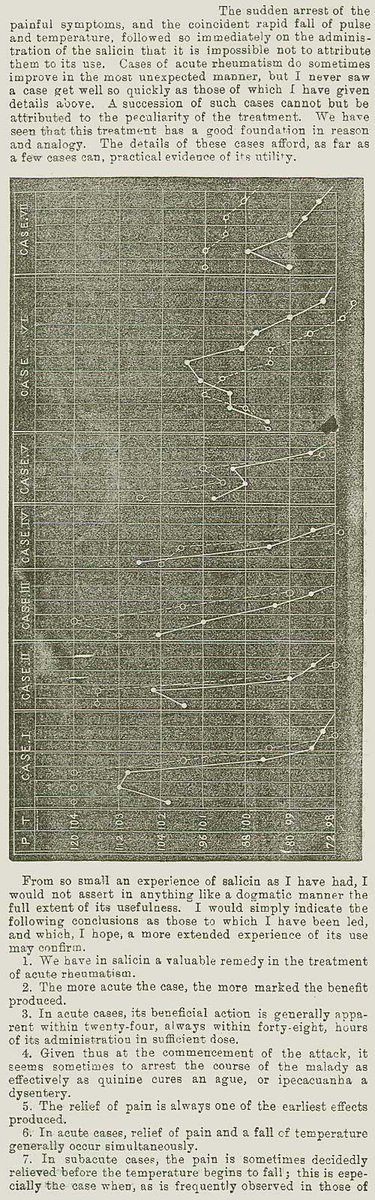

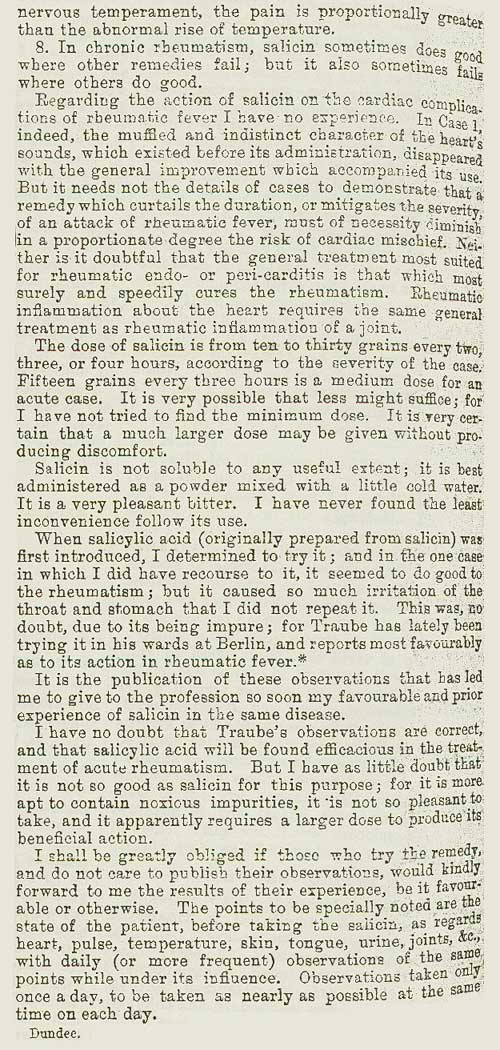

The first clinical trial of salicin was published in 1876 by Thomas Maclagan (1838–1903) from the Dundee Royal Infirmary in Scotland. In the grand tradition of self-experimentation, Maclagan first tried the drug on himself... /10

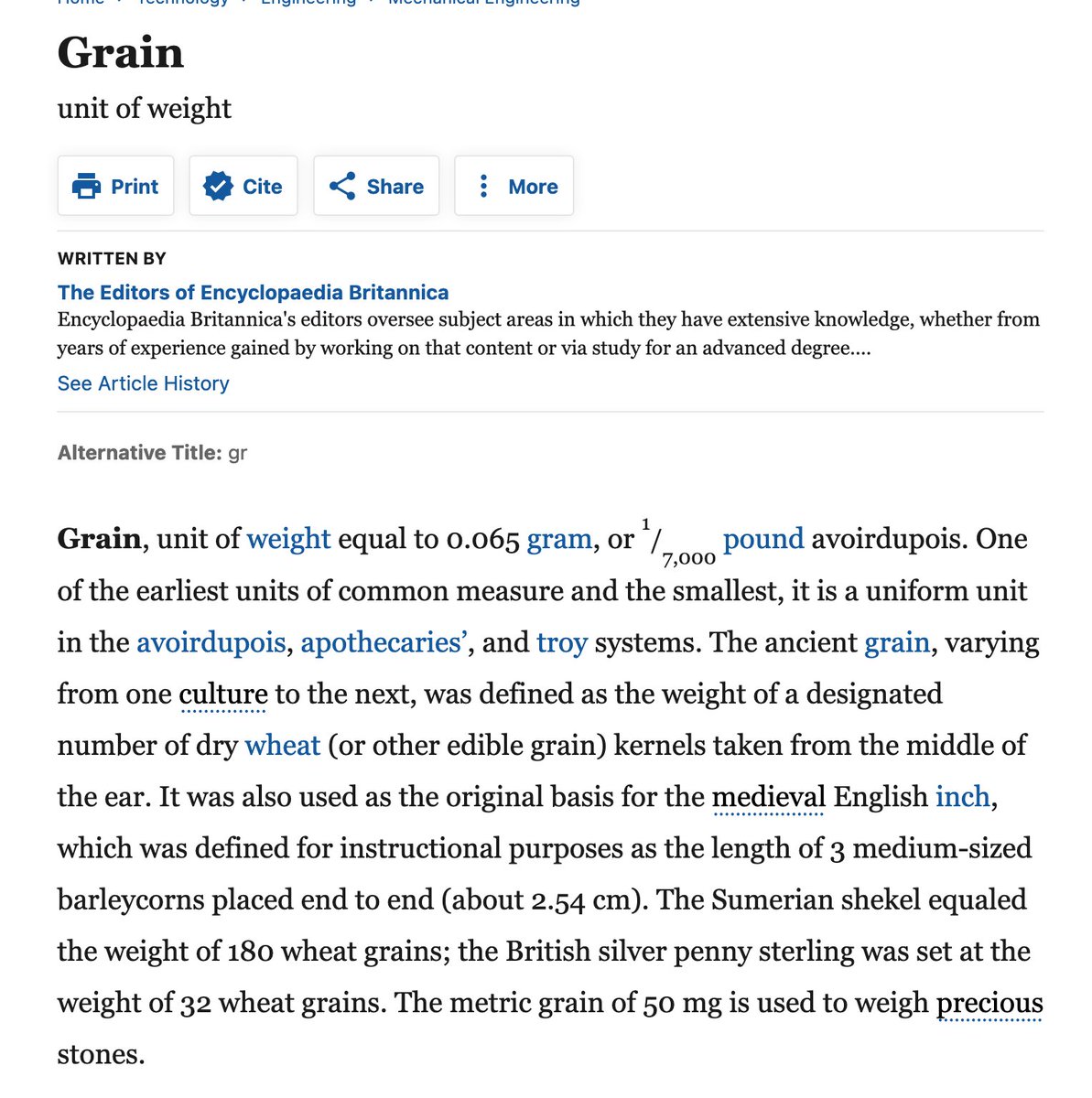

"I determined to give salicin; but before doing so, took myself first five, then ten, then thirty grains without experiencing the least inconvenience or discomfort." (More on what a "grain" is below, but some foreshadowing: that's where the 81 mg comes from.) /11

Maclagan then treated 8 patients with rheumatic fever with 12 grains of the salicin, administered every 3 hours– over 6000 mg in a day. Perhaps not surprisingly, the drug was not tolerated well; it cause lots of stomach upset./12

The search was on for less irritating forms of salicylic acid. A French chemist, Charles Gerhardt (1816–1856) had synthesized acetylsalicylic acid in 1853, but it was an unstable reaction that generated an impure form, and he did not develop it further./13

In a landmark effort in 1897, German chemist Felix Hoffmann found a new way of adding acetyl group to salicylic acid. Bayer patented the process and marketed the new drug extensively. “ASA” would go on to become one of the best selling medications of all time./14

In the 1940s, Arthur Eichengrün (1867–1949), who had been the head of pharmaceuticals at Bayer from the time the company moved from aniline dyes into drugs in 1890, claimed *he* was the one who instructed Hoffmann to synthesize ASA & Hoffmann did it without understanding why./15

Eichengrün also claimed he overrode Heinrich Dreser (1860–1924; depicted below), head of Bayer's clinical trials section, who didn’t want to pursue the drug further after some AEs. Disputes over academic credit - and squabbles between departments in industry - are nothing new./16

In 1899, Bayer began marketing ASA as “Aspirin”: a = acetyl, spir = Spiraea ulmaria (meadowsweet, a plant that also has salicylic acid). A typical dose was one teaspoon of powder in water, which worked out to about 5 grains. It came in 250 g bottles; g=grains here, not grams!/17

Around the same time, Bayer also started marketing another wonder drug synthesized by Hoffmann: diamorphine or “Heroin” (it was heroically stronger than morphine, and made you feel like a hero). Bayer marketed heroin as a non-addicting drug for cough, including for children./18

Aspirin really came into its own around this time of the great influenza pandemic – the dexamethasone of its day. In 1919, as part of the Treaty of Versailles following WW1, Bayer lost the patents on aspirin and heroin, as described here: https://medium.com/@CopyrightedDreams/brand-fallen-victim-to-world-war-e455f5cca71b

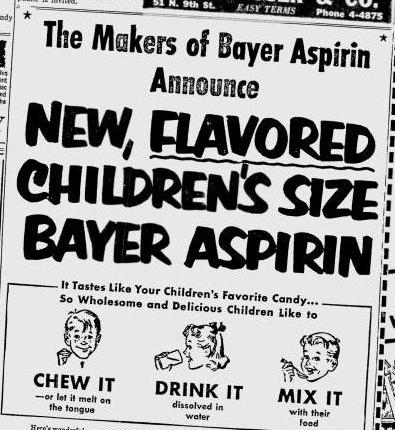

In 1922, “baby aspirin” or “children’s aspirin” began to be marketed. Arbitrarily, the dose used in this pediatric formulation was one quarter of the dose for adults, so 1.25 grains rather than 5 grains./20

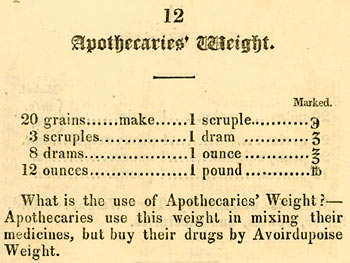

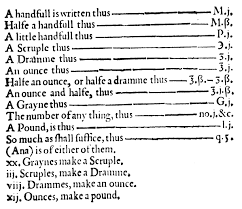

“Grains” were part of the old Apothecary System of measurement. This was a traditional system of weights in the British Isles. A “scruple” was 20 grains, dram was 3 scruples, ounce was 8 drams, and pound was 12 ounces (not 16)... And what was the grain itself?/21

A “grain” was around 65 mg; it was formally set as 64.79891 milligrams in 1953. It was based on the weight of an idealized barley cereal grain (!) and had ancient, Bronze Age trading roots. Of course, the weight of a cereal grain varies based on humidity, specific plant, etc./22

Until 1527, “Tower weights” were used in England, which were based on the slightly smaller wheat grain (~50 mg) rather than barley. And there’s one more grain related measurement we still regularly use: the carat, based on the weight of a typical carob seed (~200 mg)./23

The British pound (which has old Anglo-Saxon roots) is based on this system: “By consent of the whole Realm the King's Measure was made, so that an English Penny… shall weigh 32 Grains of Wheat dry in the midst of the Ear; 20 pennies make an Ounce; and 12 Ounces make a Pound”/24

Apothecaries’ weight is related to Avoirdupois weight, traditional system of weight in the British Imperial System and the United States Customary System, and “troy weight”. A pound is 7000 barleycorn grains./25 (End part 1 - will continue soon!)

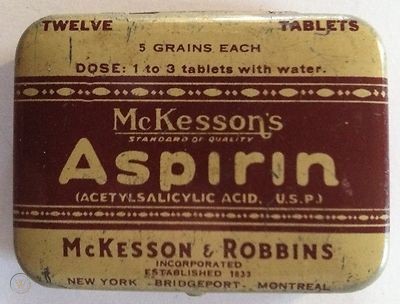

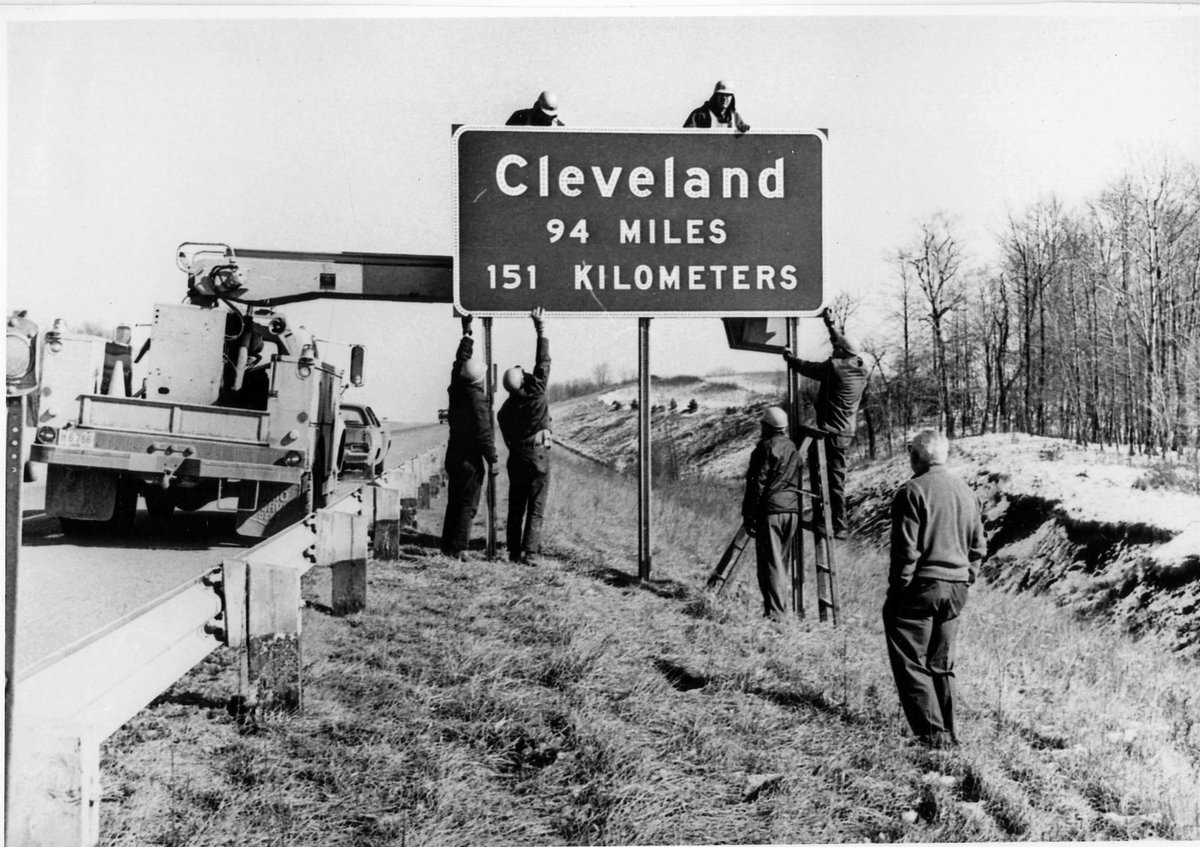

So, since aspirin dose was 5 grains (see vintage tins - the patent was gone by the time these were made), and each grain was ~64.8 mg, the 5 grain dose was 324 mg – rounded to 325 mg. “Baby” aspirin – 1.25 grains – was 81 mg. And that’s where the weird 81 mg comes from./26

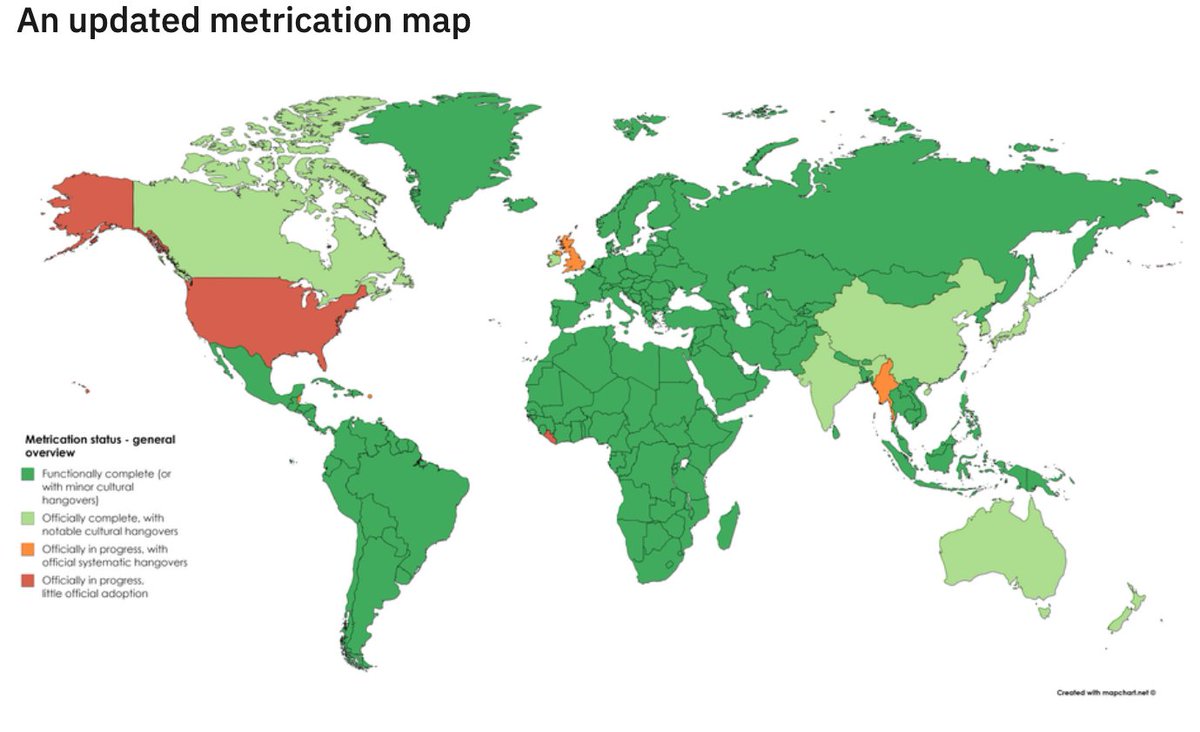

The British Pharmacopoeia finally got rid of the apothecary system in 1963, and in Europe aspirin is sold in metric doses such as 100 mg. But the US held on for 30 more years and aspirin is still sold here... in 81, 162, 325 mg doses./27

Now before you say “Americans are retrograde for clinging to the Imperial system” – yes, true, and it is a weird cultural thing, but it is complicated. There was a big push to go metric in the US in the 1970s, but the Reagan Administration cut funding for the program in 1982./28

Metrication is not complete around the globe. When I filled my tyres at a petrol station in the UK, the pump was measured in psi rather than kPa, and at the pub we ordered in pints. When I had dinner at a friend’s home in Ontario, the oven was set to 400F… etc /29

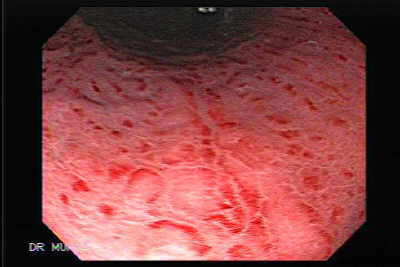

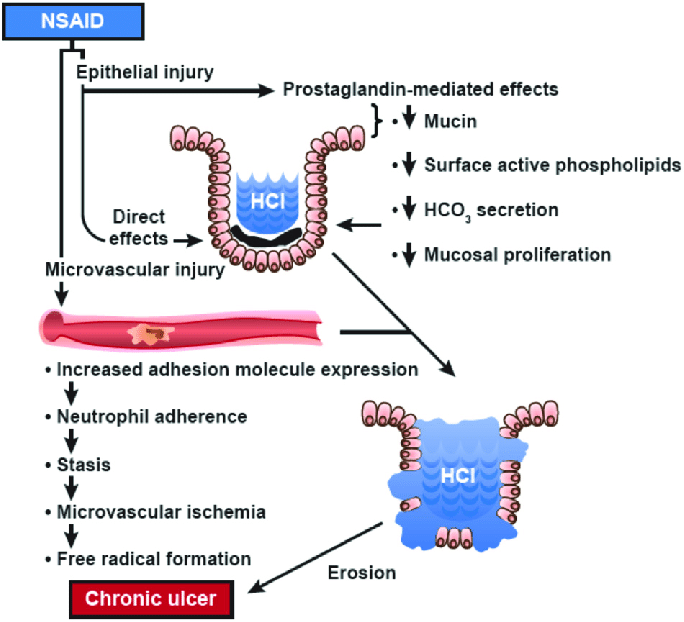

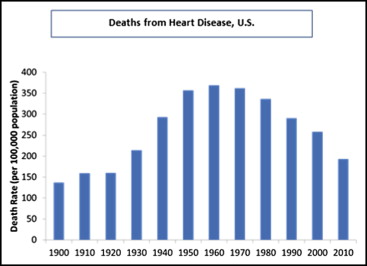

Anyway, back to aspirin. In the 1930s aspirin began to fall out of favor a bit as a treatment for fever/pain, because endoscopy was regularly performed, gastritis and was noticed routinely in people taking aspirin. (Image: Lavie C et al, Current Problems in Cardiology 2017) /30

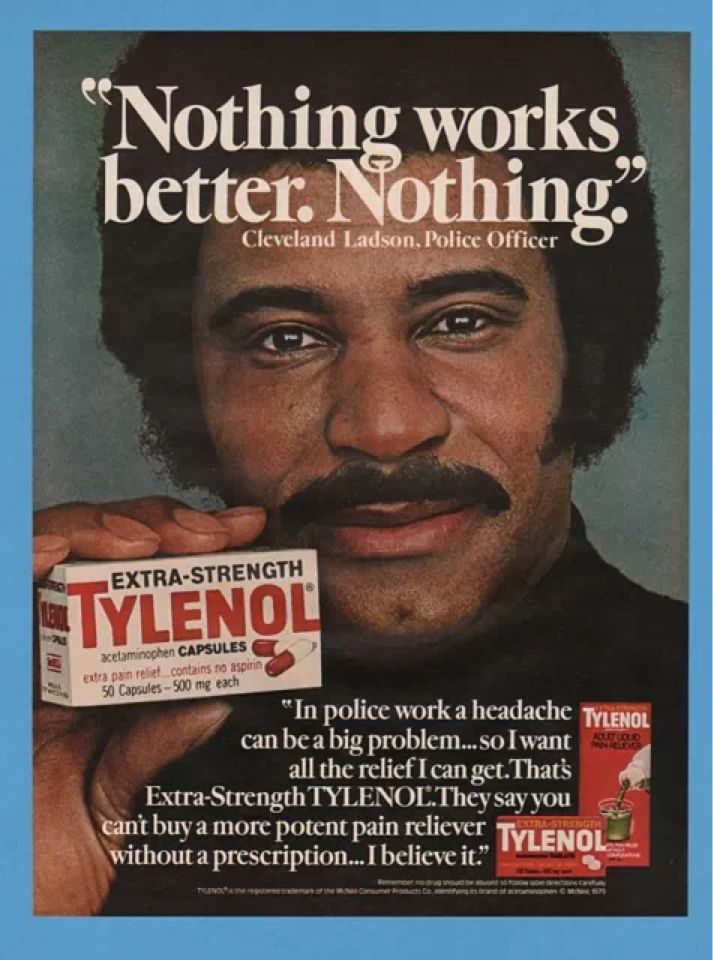

The marketing of acetaminophen beginning in 1950 (paracetamol, for those of you keeping score in the UK and countries influenced by the UK) further cut into aspirin’s use./31

But aspirin was soon to find a new life. In 1948, Dr. Lawrence Craven, a California general practitioner, noticed that almost none of his patients who were taking aspirin were having heart attacks. This was an era when MI was the most common cause of death./32

In 1950 Craven published this observation in the “Annals of Western Medicine and Surgery” – which published only 6 volumes before going defunct. It was not exactly a top tier journal, and Craven’s paper was ignored/33

In 1956, a year before dyring of an MI, Craven described 8,000 patients in a paper in the Mississippi Valley Medical Journal. Either Craven didn’t know how to pick journals or reviewers were savage. This was a critical observation that would eventually save many lives./34

Lack of understanding of the influence of aspirin on coagulation/platelet function had an influence on oncology: the platelet transfusion threshold./35

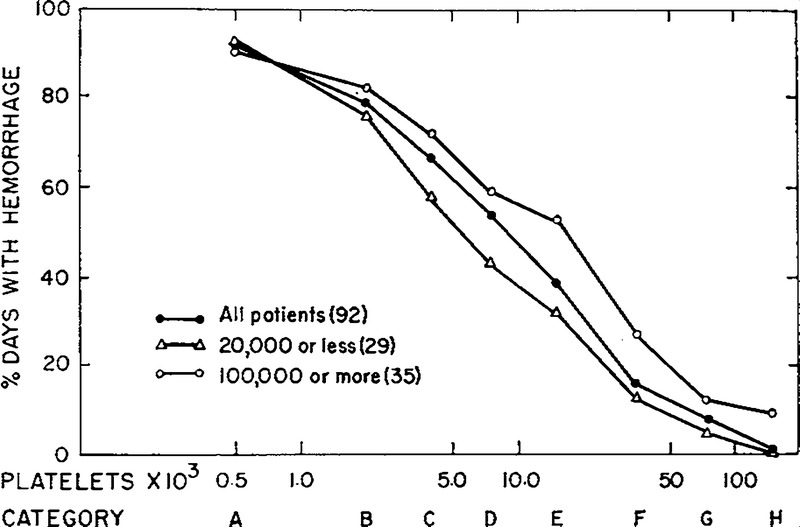

In 1962, Lawrence Gaydos and Tom Freireich published a study @nejm on platelet count and bleeding risk in acute leukemia. As a result of that study, the platelet threshold for patients getting cancer treatment was set at 20,000/mm3, which was what I learned as a med student./36

However, in 1962 patients were being given aspirin liberally as an antipyretic, and the effect of aspirin on platelet function and bleeding wasn’t recognized. In 1966, Armand Quick first noticed that the bleeding time was prolonged in people taking salicylates./37

Then in 1967, Harvey Weiss at Mt Sinai and Louis Aledort at Einstein reported in @TheLancet that aspirin inhibited platelet function... release of ADP... somehow. /38

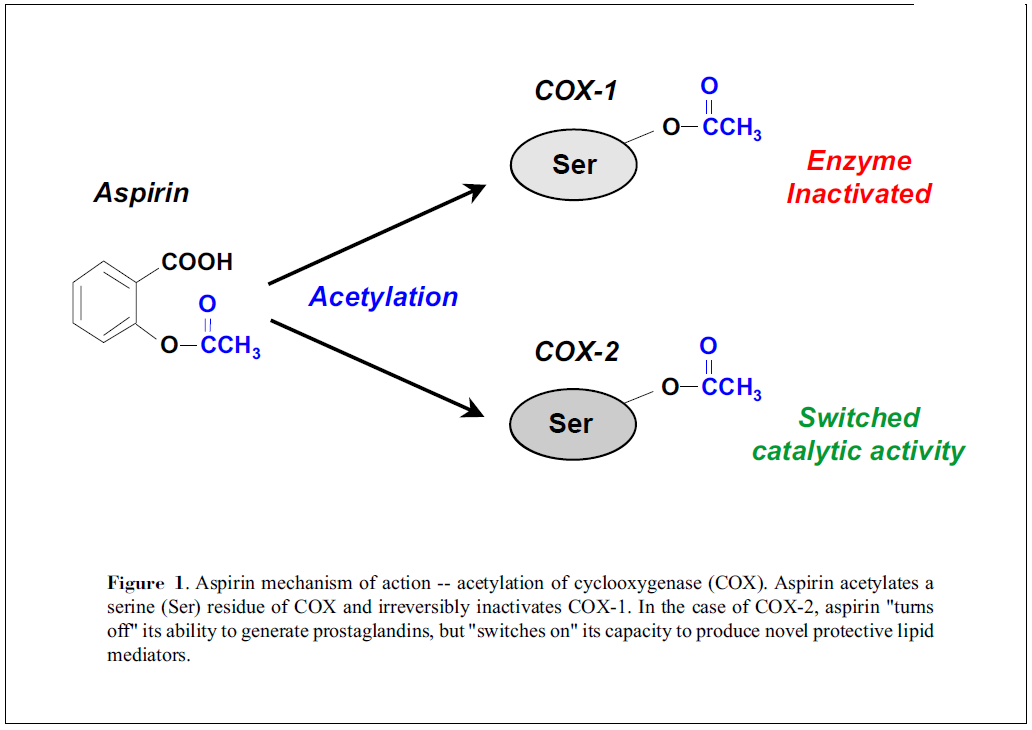

In the early 1970s, John Vane, professor of pharmacology @ucl, figured out that aspirin’s mechanism of action is dose-dependent inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. In 1982 he won a Nobel prize along with Swedish biochemists Bengt Samuelsson and Sune Bergström./39

In 1976 cyclo-oxygenase was discovered (purified from sheep seminal vesicles, of all places) - an enzyme that is strongly inhibited by aspirin, altering the balance between arachidonic acid, thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin. (Figure: Chiagng et al, )/40

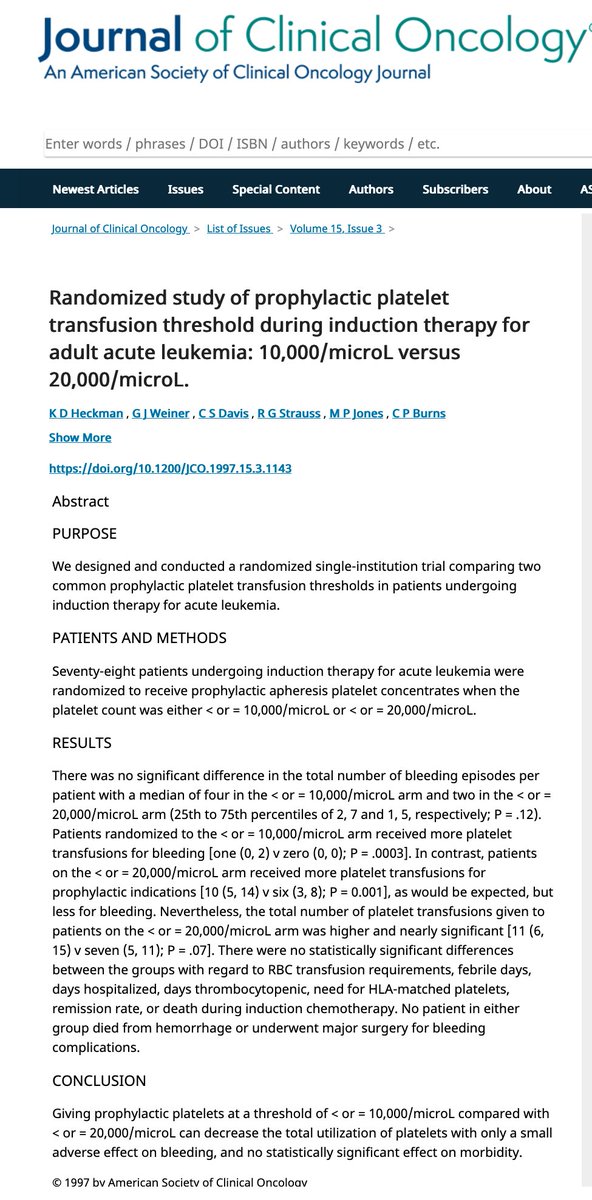

So beginning in the 1990s, the platelet threshold for transfusion was revisited - and revised. Rebulla and colleagues (GIMEMA) published a randomized trial of 270 patients in 1997 in @nejm. Heckman et al found the same in a 78 patient single-center trial @uiowa./41

Several other studies were published 1998-2001, and now the most commonly used platelet transfusion threshold for afebrile, asymptomatic patients with cancer is 10,000/mm^3./42

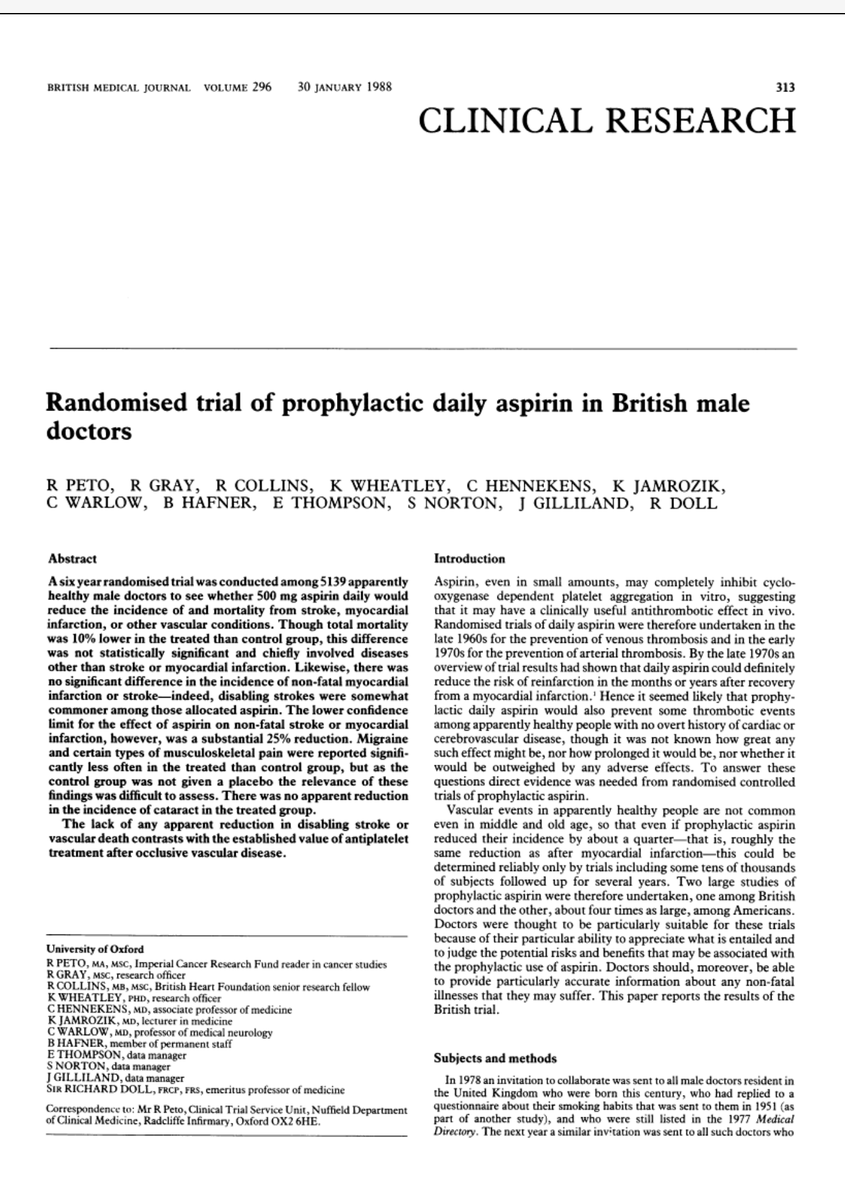

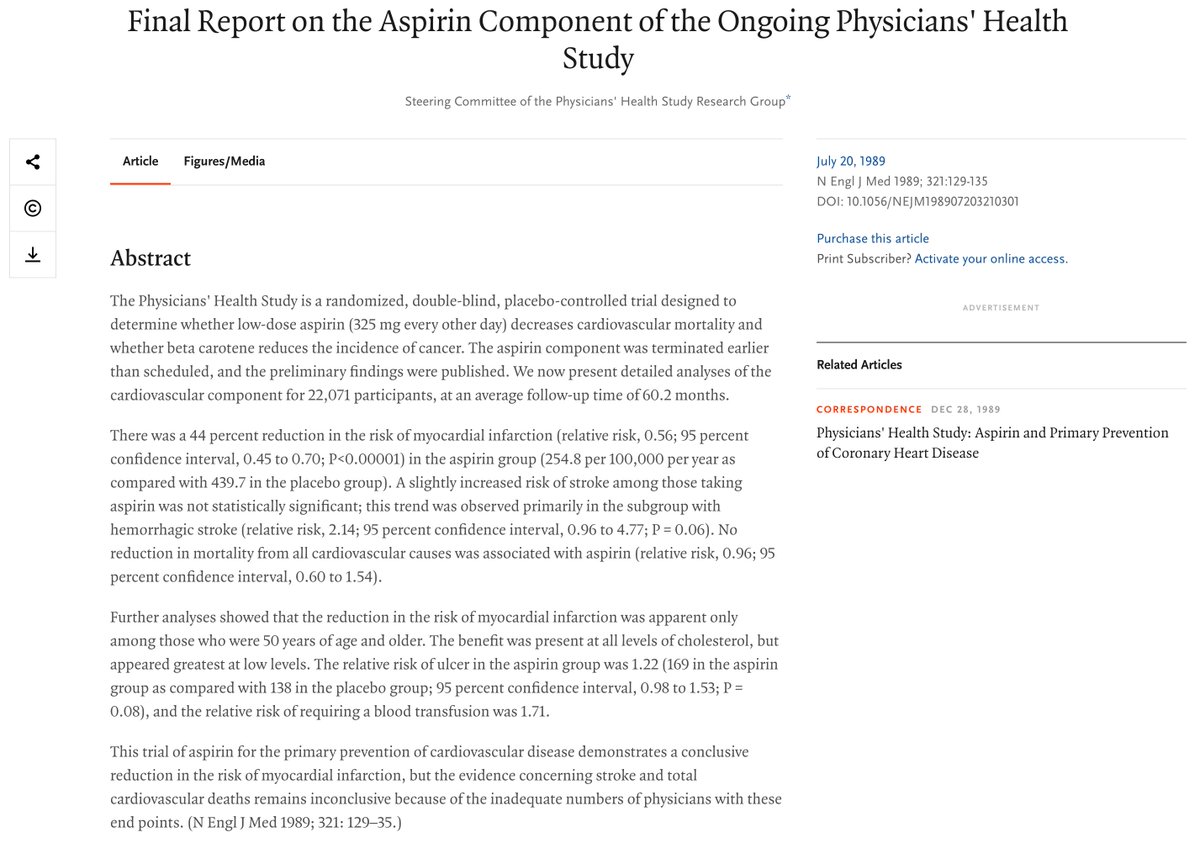

We don’t have space to go into all of the studies that established the use of aspirin in secondary cardiac prevention (and to a lesser extent primary prevention), but some of the key ones were the 1989 Physician’s Heart Study and the 1988 British male doctor study./43

Ironically, one of the early advertising points for aspirin, as in this early @Bayer ad, had been that it had no effect on the heart! /44

Two more points. When I was a little kid and would have a fever, I’d almost always get an aspirin for it. Eating the chalky orange stuff from Bayer, or this box of St Joseph’s baby aspirin with the British soldier on it, is one of my earliest memories./45

Nowadays you would never give a kid aspirin. Why? Reye syndrome. While there were hints that aspirin sometimes did bad things to kids (eg Mortimer/Lepow case in 1962), the first detailed description of Reye syndrome was in 1963 by Douglas Reye, an Australian pathologist./46

In 1980, Karen Starko in Arizona and her colleagues published a small case-control study in that found the first statistically-significant link between aspirin use and Reye syndrome. The CDC began cautioning parents not to use aspirin for kids that same year, 1980./47

@FDA mandated warning labels on aspirin in 1986, instructing parents and guardians not to give aspirin to children or adolescents under age 19. In other countries the packaging said age 16. So now 81 mg aspirin is “low dose” rather than “baby”./48

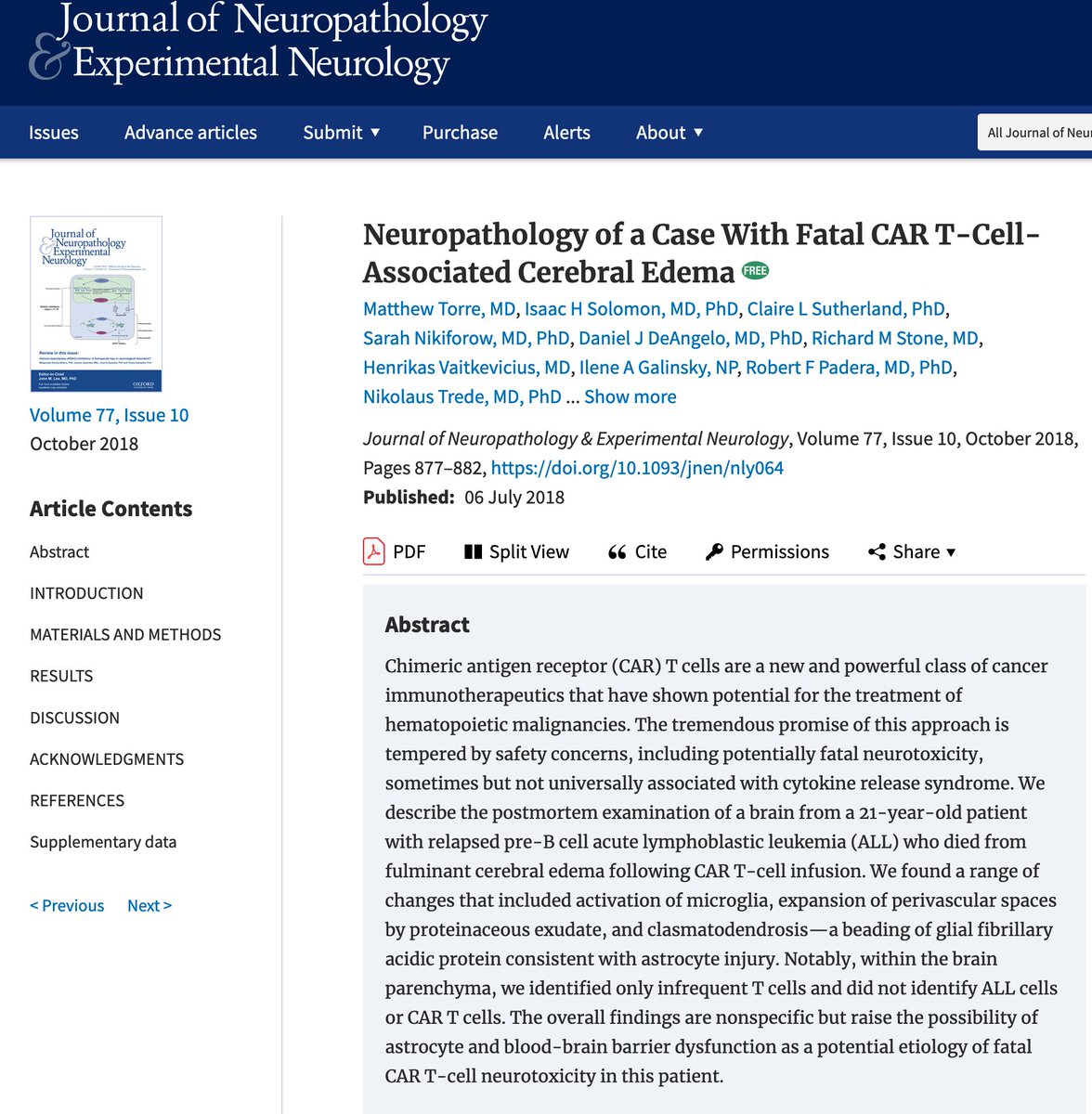

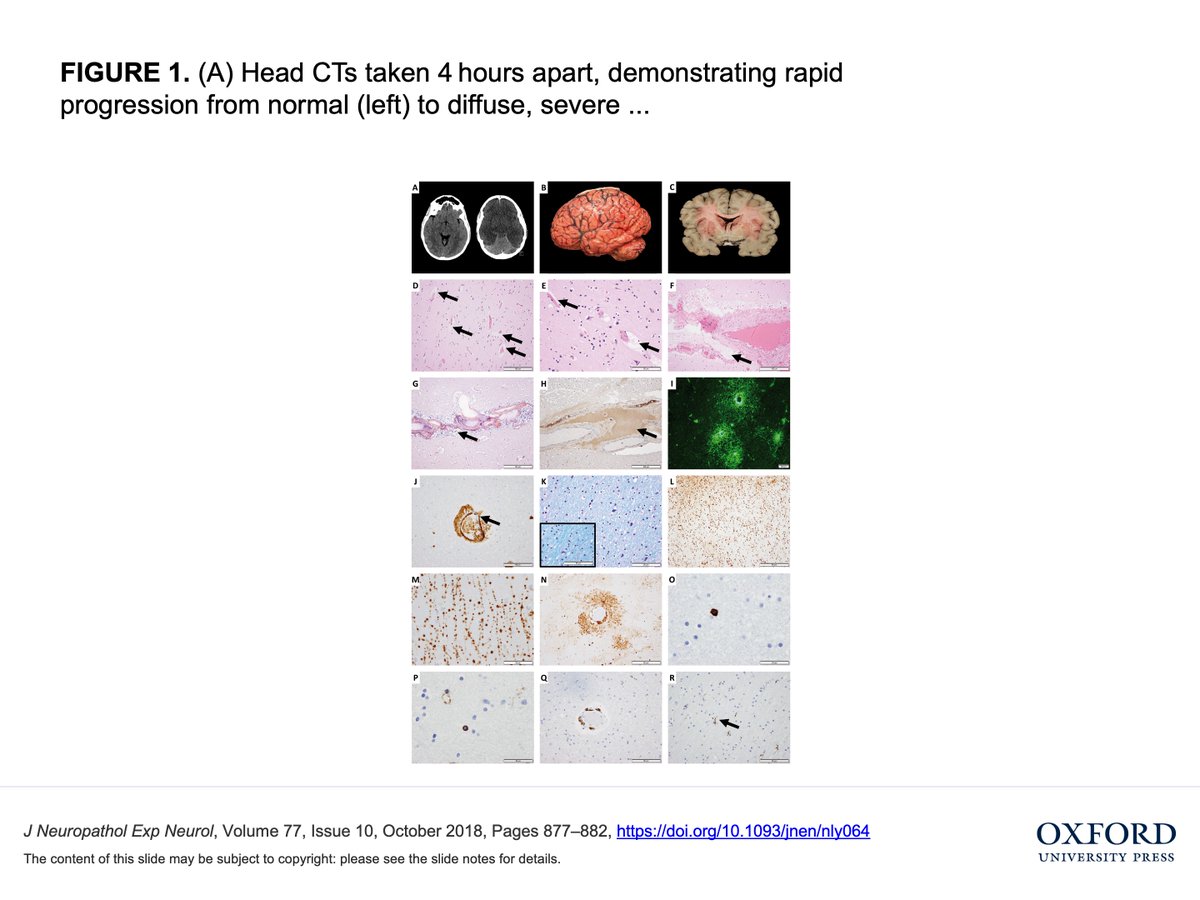

I dated a girl in college who had a cousin who died of Reye syndrome in the late 1970s, so it is not too ancient. But I had largely forgotten about Reye syndrome until... /49

... a 21 year old patient at our center died of encephalopathy in 2016, triggered by a Juno CAR-T product. A senior pathologist at autopsy said he had not seen such dramatic treatment-associated brain edema "since the Reye syndrome era". This case was written up./50 (Cont'd)

In 2006, a survey indicated 36% of US adults – more than 50 million people – were taking aspirin, either daily or every other day for cardiovascular risk reduction, or for other indications such as colorectal cancer prevention (data are less strong for that)./51

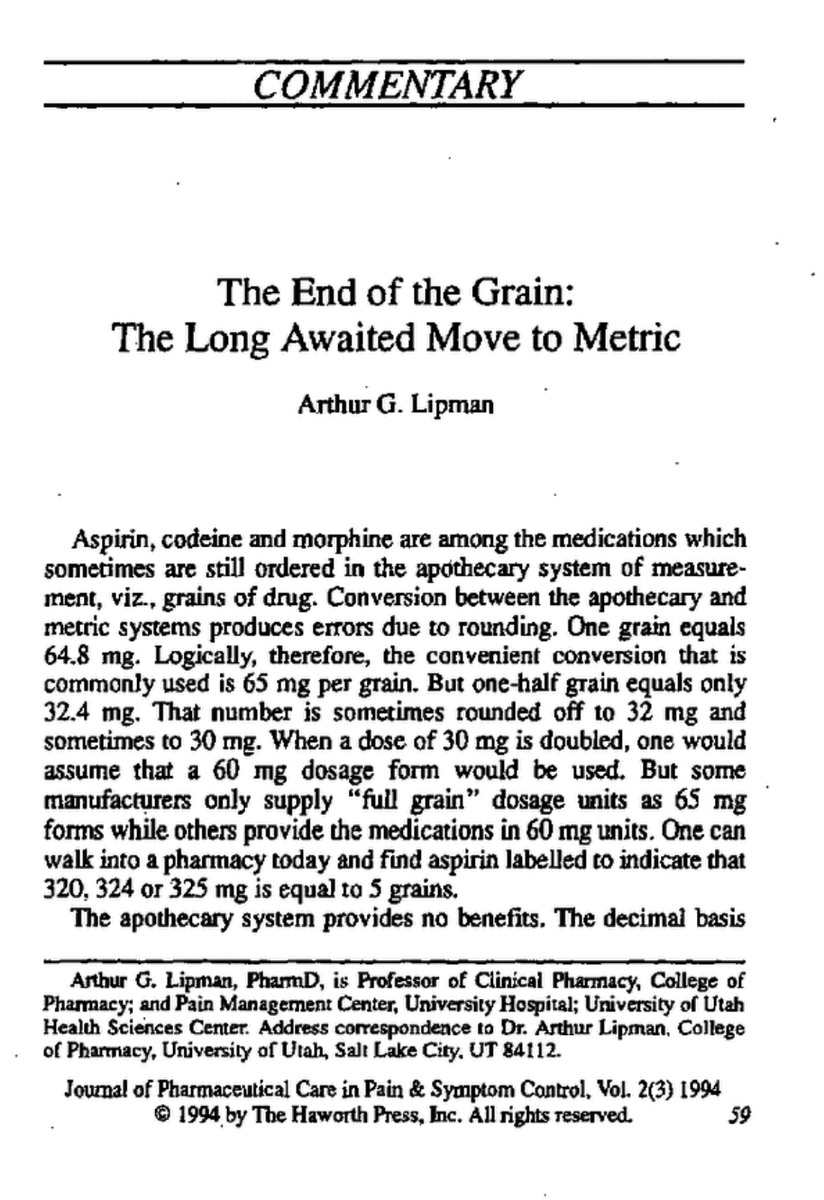

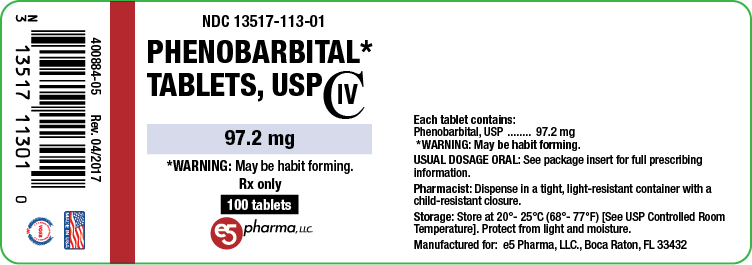

Phenobarbital dosing is one. It was a late holdout on metric conversion. The first time I wrote for this drug as an intern (which was one of the last times, too) the dose the patient was taking was 97.2 mg PO BID (1.5 grains). The drug is rarely used today- and always metric./53

Acetaminophen dosing, even though it debuted in the 1950s, is another relic. Regular Tylenol=325mg=5grains. “Extra strength” branded Tylenol may be 500 mg, but 325-650 mg doses (i.e., 5-10 grains) are sold commonly. Weird that 650 mg is not “extra strength” but 500 mg is…/54

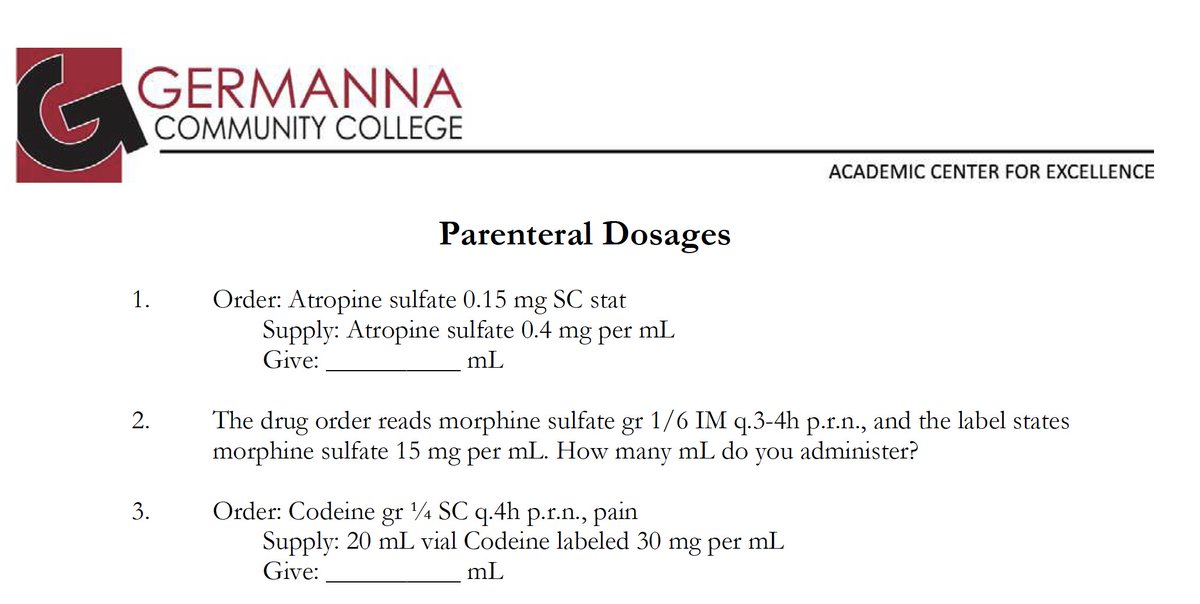

Codeine also used to be measured in fractions of grains. Typical codeine doses today range from 15 mg to 30 mg to 60 mg, which is just rounding from ¼ (16.2 mg), ½ (32.4 mg) and 1 grain (64.8 mg)./55

Morphine was once commonly prescribed in grains, too, but now is always metric. Still, a few nursing and pharmacy intro courses in some places teach conversions. But in 2020, any joker doctor who orders “1/6 grain” morphine should be taken aside for a behavior correction./56

Are there more? Let me know if you think of any./57

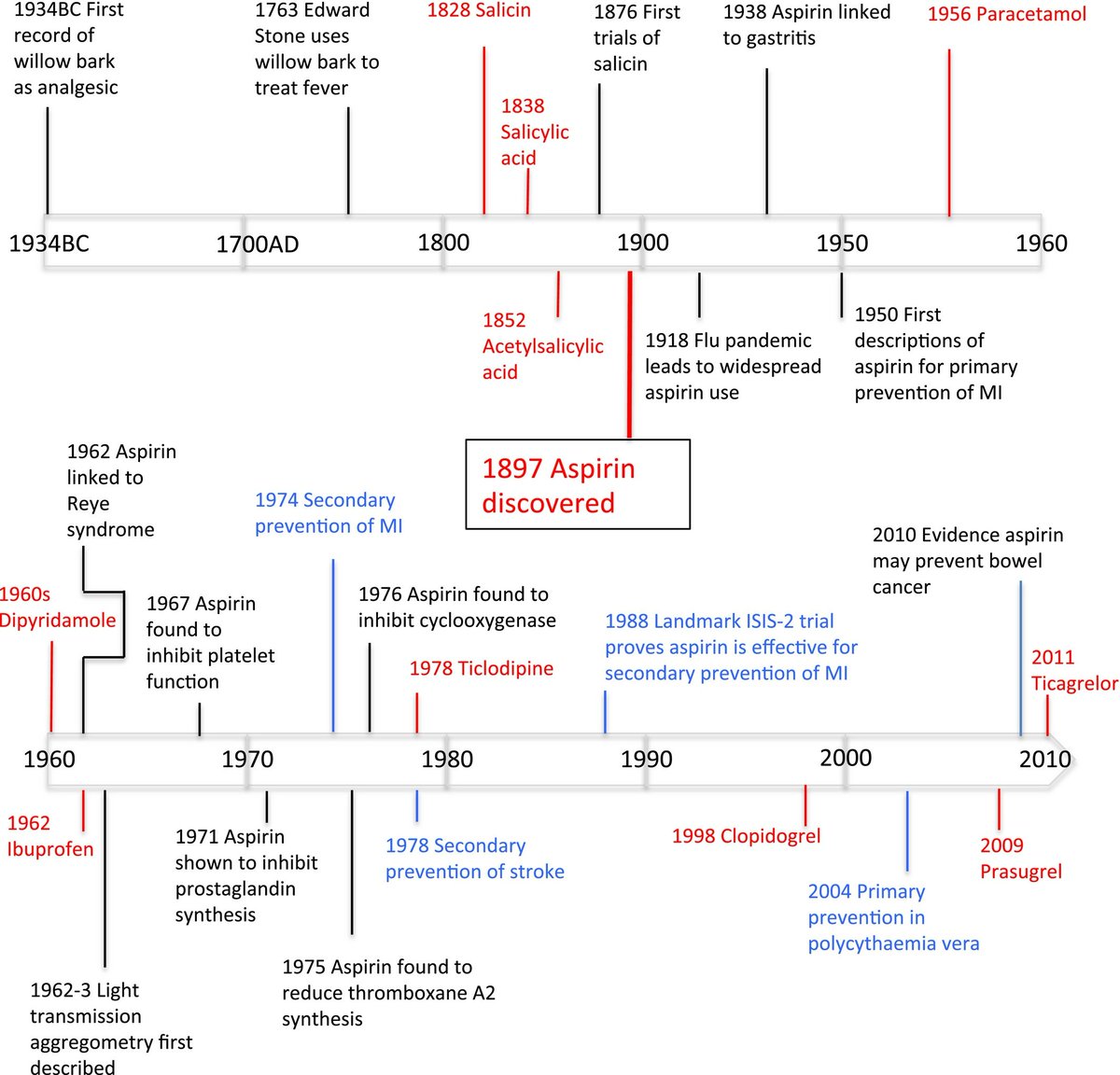

Here’s a nice timeline of aspirin history by @mike_desborough and David Keeling, published in 2017 in @BritSocHaem/58

And I also liked this short review about the weird dosing of aspirin and its origin in barleycorn grains, by Joshua Novack:/59

https://www.clinicalcorrelations.org/2019/02/22/the-history-behind-aspirin-81/

https://www.clinicalcorrelations.org/2019/02/22/the-history-behind-aspirin-81/

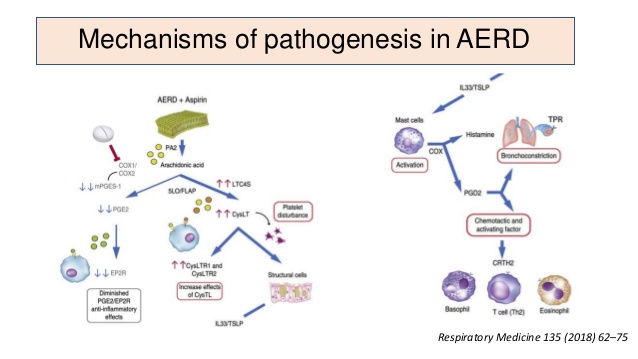

And that's about it for aspirin. I could have discussed various MPN aspirin trials, aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease (AERD), the controversy over optimal ASA dose between individuals for adequate CV prevention. But all threads must come to an end, as the 3 Fates know. /60

/60

/60

/60

Weirdly, aspirin is my personal kryptonite - the one thing that I'm allergic to. I've had two attempts at desensitization; the 1st put me in an ER with hypotension & uvular edema & got me an Epipen shot, the 2nd I got to 1300 mg/d but caused gastritis. So no ASA for this guy. /61

Hopefully the terrific @TanyaLaidlawMD of the AERD Center @BrighamWomens and her colleagues can figure out why this strange sensitivity happens to some of us (it started in me at age 34 after a URI - never had problems with ASA before), and how to make it stop./62

Finally - if anyone knows how to Tweet more than 25 tweets at a time, please let me know. With these long threads, I have to put them out piecemeal in blocks of 25, and I don't like to leave people on a cliffhanger!  Enjoy. see you at #ASH20. /63End

Enjoy. see you at #ASH20. /63End

Enjoy. see you at #ASH20. /63End

Enjoy. see you at #ASH20. /63End

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter