WHY HAS BRITISH ARMY RENEWAL BEEN SO PROBLEMATIC?

Having made the point about the need for urgent modernisation, I want to try and explain why achieving this has proved to be so challenging. Our story starts in 2000, a decade after the Cold War ended.

1/

Having made the point about the need for urgent modernisation, I want to try and explain why achieving this has proved to be so challenging. Our story starts in 2000, a decade after the Cold War ended.

1/

At this time when we were not involved in any major conflict.

Deployments to Iraq, former-Yugoslavia, and Sierra Leone had shown how difficult and expensive it was to generate, position and sustain capable land forces in an expeditionary context.

2/

Deployments to Iraq, former-Yugoslavia, and Sierra Leone had shown how difficult and expensive it was to generate, position and sustain capable land forces in an expeditionary context.

2/

Since the forward basing of units ties-up forces that can’t be used elsewhere, the need for a medium weight capability to make the Army more deployable and easier to support was identified. This was the impetus behind programmes like FFLAV, MRAV (Boxer) and FRES.

3/

3/

The idea was to develop a family of vehicles that was highly mobile and air transportable, yet still provided high levels of protection in a sub-20-tonne package. The US Army nailed it with Stryker. But we decided we wanted better protection.

4/

4/

Although we were doing great things with lightweight composite armour (see Foxhound) the technology could not deliver the weight savings we wanted. The shenanigans of the early noughties prevented new vehicles being fielded while wasting precious resources. (image: GDLSUK)

5/

5/

@ThinkDefence has covered this topic in detail. Suffice it to say it wasn't our finest hour. By 2007, we'd spent £400m with nothing to show for it. Then, the global financial crisis of 2008 tanked the economy. By 2010, burgeoning government debt resulted in deep defence cuts.

6/

6/

While the above scenario was playing out, British troops were deployed in Iraq & Afghanistan. With the Army focused on counter-insurgency ops, little attention was paid to high-end capabilities, with many people saying that heavy armour was obsolete.

7/ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53909087

7/ https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-53909087

Much to the Army’s credit, it recognised the ongoing importance and utility of heavy armour and sought to upgrade it. While it might have been too much to ask for new MBT and IFV, platforms, obsolescence and upgrade programmes for Challenger 2 and Warrior were initiated.

8/

8/

Challenger 2 LEP and Warrior CSP were well measured projects given financial exigencies of the time. The problem was that between 2010 and 2016, the provision of cash was so sparse and with such extended programme delivery timelines that progress was glacial.

9/

9/

In 2014, Russia annexed the Crimea. As we watched the conflict unfold, the Army realised how right it had been to fight for the retention of heavy armour. As the Ukraine Army re-learned old lessons, it caused a massive re-set of NATO's high-end war fighting capabilities.

10/

10/

It was at this point that we should have questioned the scope of the Challenger 2 LEP and Warrior CSP. While we was decided that they were sufficient, our NATO allies and partners embarked on more extensive renewal programmes.

11/

11/

Whatever the Army thought it ought to do, it was told there was no money. Another home truth was that the Army would never have the mass to match the conventional might of Russia or China. It needed to fight smarter. Thus, the Strike concept was born.

12/ https://wavellroom.com/2020/01/07/strike-brigades-more-than-just-a-medium-weight-capability/

12/ https://wavellroom.com/2020/01/07/strike-brigades-more-than-just-a-medium-weight-capability/

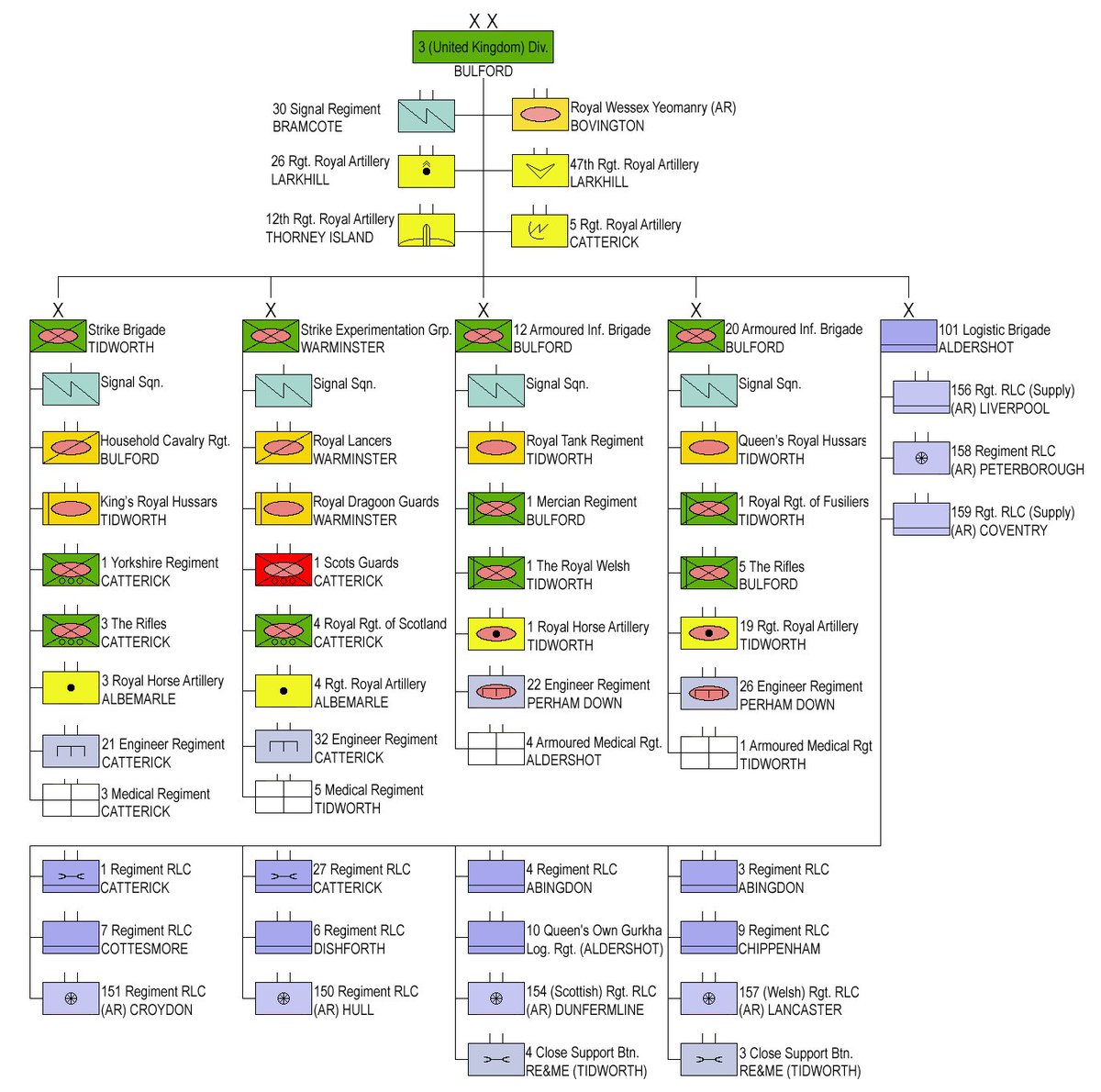

Army regeneration was channeled into two primary areas: Strike Brigades and Armoured Infantry Brigades. These were complemented by 16 Air Assault and 3 Commando brigades, plus a range of light role infantry to create the Army 2025 plan. (Image: @noclador)

13/

13/

As the Army developed its future force blueprint, recent conflicts suggested that making the Strike/ AI concept work would require wider investment in a range of enabling capabilities, including artillery, UAVs, GBAD, C4I, EW & Cyber. There was just one problem. Money.

14/

14/

Politicians appreciate the utility of warships, submarines, and combat aircraft. What they don’t understand is that land forces are like orchestras: they need lots of separate bits to be effective. When fundamental renewal is needed, armoured brigades are a tough sell.

15/

15/

At a macro level, the situation is like a roof. If you repair it on an ongoing basis, you can sustain it indefinitely. But if you let one hole appear after another, eventually you reach a point where you have to replace the whole thing. The Army has now reached this point.

16/

16/

In an ideal world, the Army would have three divisions: a Strike division, an Armoured division, and a Rapid Reaction division. Unfortunately, having such aspirations is like living in cloud cuckoo land. We can't even afford the Army 2025 plan that emerged in 2015.

17/

17/

This is why the integrated Review is important. Love it or loathe it, Brexit is an opportunity to take a step back and reconsider Britain’s place in the world. In doing so, it allows us to re-align our defence commitments with a more focused foreign policy agenda.

18/

18/

Then there is the economic impact of the global pandemic. Substantially reduced resources means the future force must be affordable and sustainable going forward. In other words, the Army's major equipment renewal programmes have been overtaken by events.

19/

19/

If previous assumptions are no longer relevant, we risk spending money on capabilities that we no longer need. So, we have reached an inflection point where we must ask ourselves whether initiatives conceived more than a decade ago are still relevant.

20/

20/

At a deeper level, we need to ask ourselves which defence commitments are mandatory and which are discretionary. The answer will require us to make hard choices. None of this is easy. But whatever we decide, we need to get on and do it, to restore morale and credibility.

End/

End/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter