1/ Two Centuries of Black Migration Led to Democrats’ Victory in 2020 (The Deep Demography That Structures American Politics — as posted on Medium via @newamericanhist )

2/ The subtleties and surprises of the 2020 presidential election have been explored from every possible angle: ethnicity and gender, the suburbs and the cities, continuities and changes between 2016 and 2020

3/ In many ways, however, the broad outlines of the election of 2020 — like the elections of the last half-century — are products of the 1820s and 1920s.

4/ Fundamental contours of the electorate were defined by the migrations of Black Americans, first in the forced movements of enslavement and then in the bold movements of the Great Migration and succeeding generations.

5/ The pattern is evident in a comparison between the 2020 map and a map from 200 years before. The 2020 county-level map reveals a band of Democratic votes stretching across the South from Virginia to the Mississippi Delta.

7/ That band has been in place for two centuries, the result of the forced migration of Black people, in slavery, to the richest agricultural lands in the country — the so-called Black Belt.

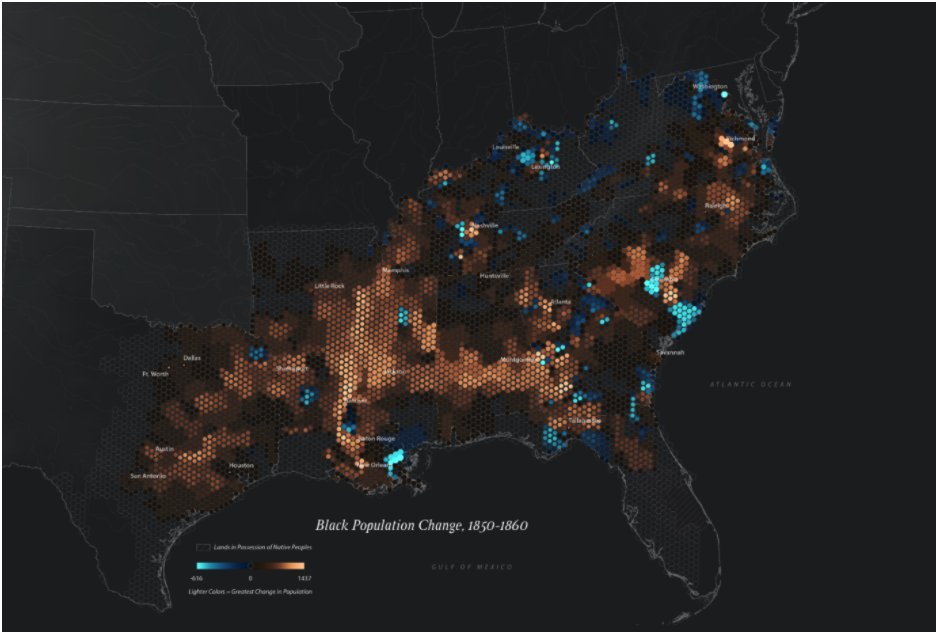

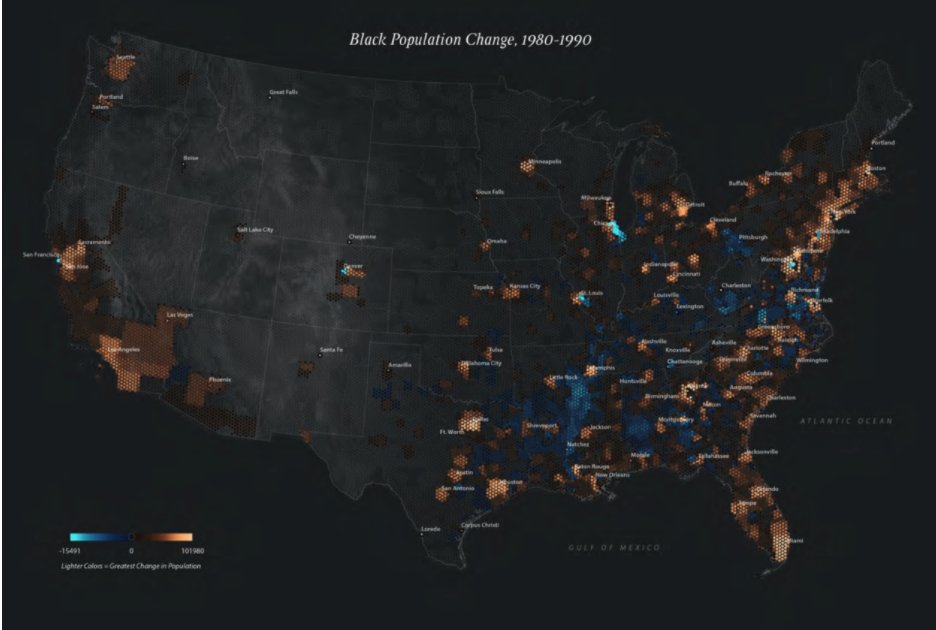

8/ The following map of Black population change in the 1820s, when the domestic slave trade carried enslaved people into lands being taken from Native peoples, shows the beginning of that pattern.

9/ (In this map, and those that follow, brown-shaded areas indicate population increase; blue indicates population decrease.)

10/ Over the next three decades, that forced migration would spread into Texas, concentrating Black people in areas that would contain the great majority of the nation’s Black population.

11/ Over a million enslaved people suffered movement from the Upper South into the plantation areas of the Cotton South.

12/ The concentration of Black people held profound political meaning even in slavery, for the white men who controlled those places held disproportionate power in their states and in the nation, thanks to the three-fifths clause of the U.S. Constitution.

13/ White men determined to continue the spread of slavery launched the Confederacy in 1860 to sustain that power, unchallenged in a new nation of their own making. The war they began, however, destroyed the very system of slavery they sought to protect.

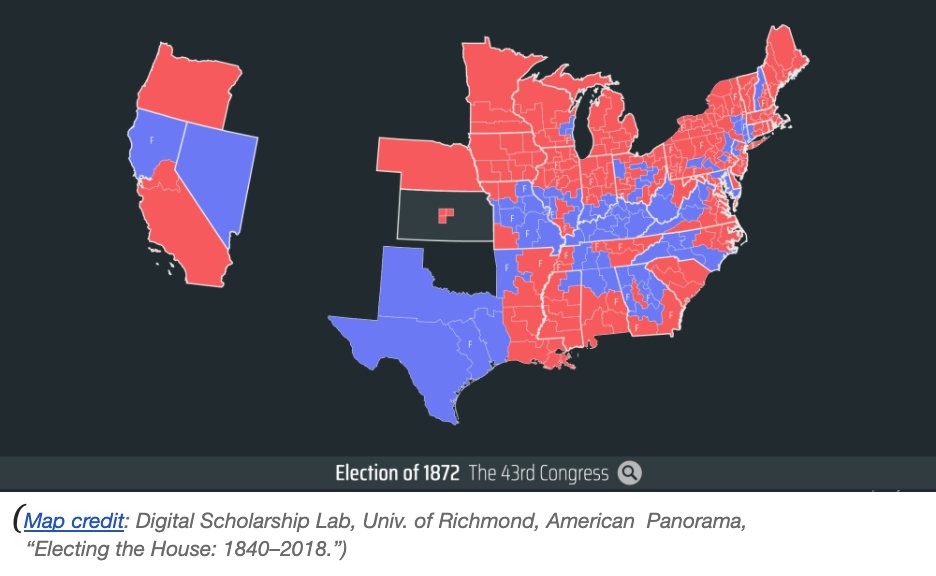

14/ After the resulting emancipation, in Reconstruction, the Black majority in these counties built political power with remarkable speed and efficacy. Formerly enslaved people embraced citizenship and its responsibilities with an understanding that astounded white observers.

15/ Wherever they had sufficient numbers, Black southerners consolidated their new and fragile franchise to support Republicans, Black and white, who sought to protect their fragile new rights of citizenship and self-determination.

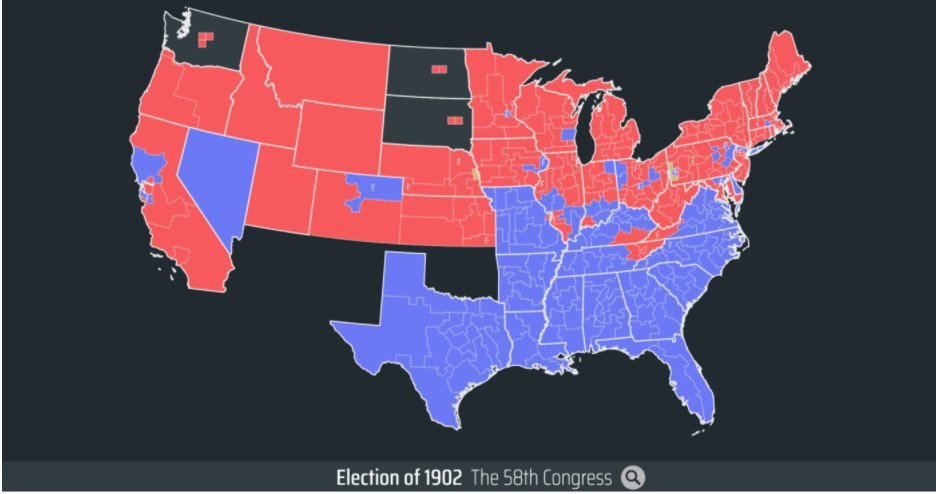

17/ The power of Black voters was systematically stripped away by white southerners, however, in the decades that followed, through violence and systematic disenfranchisement.

18/By 1902, the South had become solidly Democratic as white southerners closed ranks against the Black people among whom they lived.

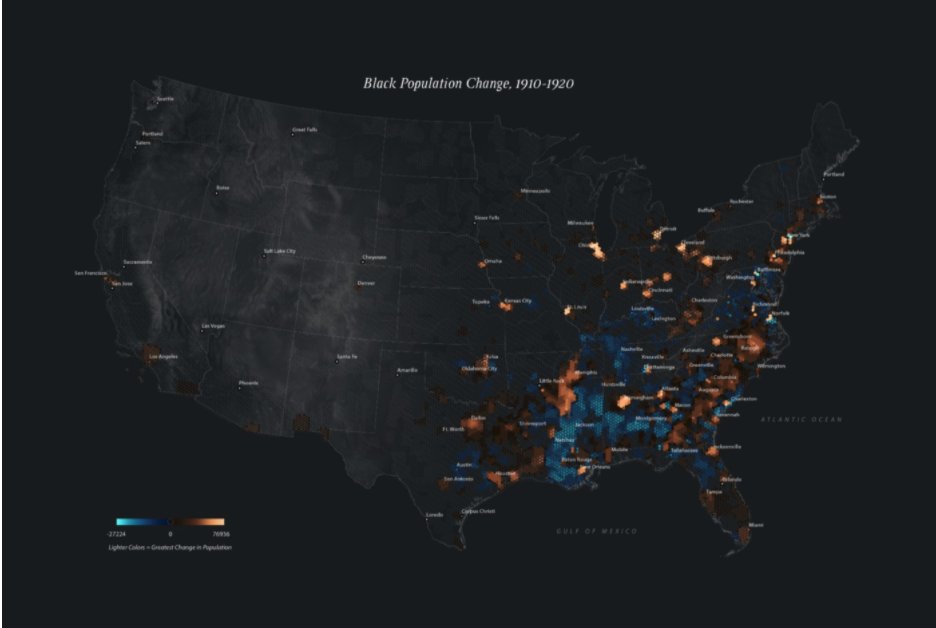

19/ Black southerners, confronted with this and other injustices, fled the South by the millions at the first opportunity.

20/ During World War I, when the tides of immigration from Europe ended just as demand for northern industry escalated, Black southerners fled the southern countryside, …

21/ ...pushing their way into cities throughout the South, but also in the Northeast and Midwest, and eventually, in California as well.

22/ In the cities of the North, Midwest, and West, Black people built political power, cementing their relationship to the Democratic party even as the Republicans remained strong in their states.

23/ White Democrats in the South fought against the rise of Black influence in the party, launching the Dixiecrat movement in opposition to the integration of the armed forces by Harry Truman.

24/ That unstable relationship broke with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, when Black southerners were finally able to register — and vote — in large numbers.

25/ The ensuing white reaction was just as consequential, made evident in support for George Wallace in 1968, and in the Republicans’ so-called Southern Strategy of the early 1970s, when Richard Nixon appealed to white voters who had long voted for Democrats.

26/ In the meantime, a remarkable reverse migration of Black Americans began and then gathered force: Black people moved in large numbers to the suburbs, especially in the South.

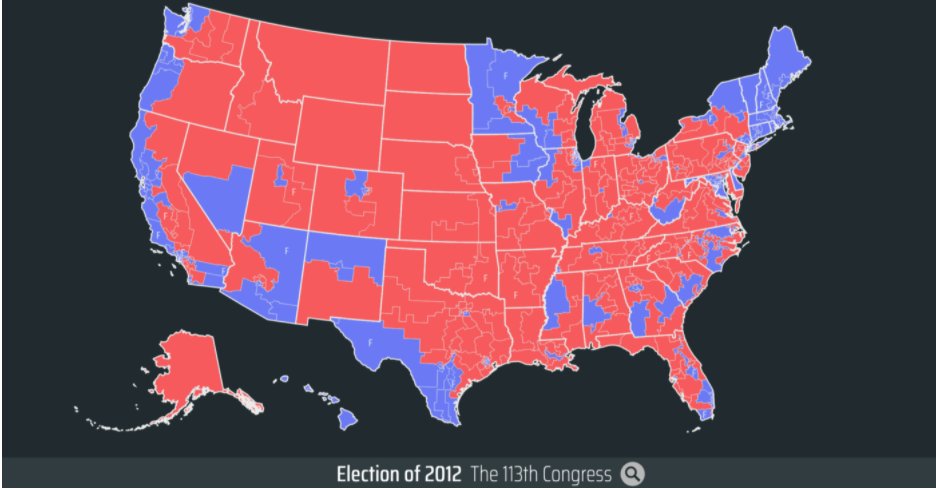

27/ By 2012, the pattern of 2020’s election had crystallized on the congressional level, as districts with large Black populations, rural and urban, voted for the Democrats and white people voted heavily for the Republicans.

29/ In 2016, the Hillary Clinton campaign neglected cities in the Midwest and Northeast, perhaps taking the votes of the grandchildren of the Great Migration for granted. As it turned out, Black voter turnout fell considerably that year, reversing a 20-year trend.

30/ Building on their strength of numbers and resolve, Black voters in South Carolina helped Joe Biden secure the Democratic nomination. Soon thereafter the votes of Black people in cities throughout the nation played a critical role in his ultimate victory.

31/ Black women proved especially loyal and active. The work of Stacey Abrams and her allies in Georgia mobilized the Black electorate as never before. The future of the Senate will depend on whether Democrats in Georgia are able to build on that accomplishment.

32/ The fundamental structures of American party identity, then, turn around the loyalty of Black Americans to the Democrats and the opposing loyalty of many white Americans to the Republicans.

33/ The variances that brought the presidency to Donald Trump and then to Joe Biden are of crucial importance, but they are just that: ...

34/ ...changes at the boundaries of the fundamental geographic divisions of the electorate, boundaries born over the last two centuries by forced and then free Black migration.

35/ The consequences of demography are not destiny. Disenfranchisement, voting rights, gerrymandering, racial redistricting, voting restrictions, and voter mobilization have altered, often abruptly, the meaning of demographic patterns.

36/ They will do so again. To grasp their possibilities, however, we must understand how such fundamental patterns emerged in the first place.

37/ The consequences of demography are not destiny. Disenfranchisement, voting rights, gerrymandering, racial redistricting, voting restrictions, and voter mobilization have altered, often abruptly, the meaning of demographic patterns.

38/ They will do so again. To grasp their possibilities, however, we must understand how such fundamental patterns emerged in the first place. (Explore more maps from this thread @americanpano @UR_DSL).

Want to teach with these maps? Explore more? https://www.newamericanhistory.org/

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter