A word I've been thinking about in my research a lot lately is 'encyclopaedic' and its application by modern scholars to medieval maps.

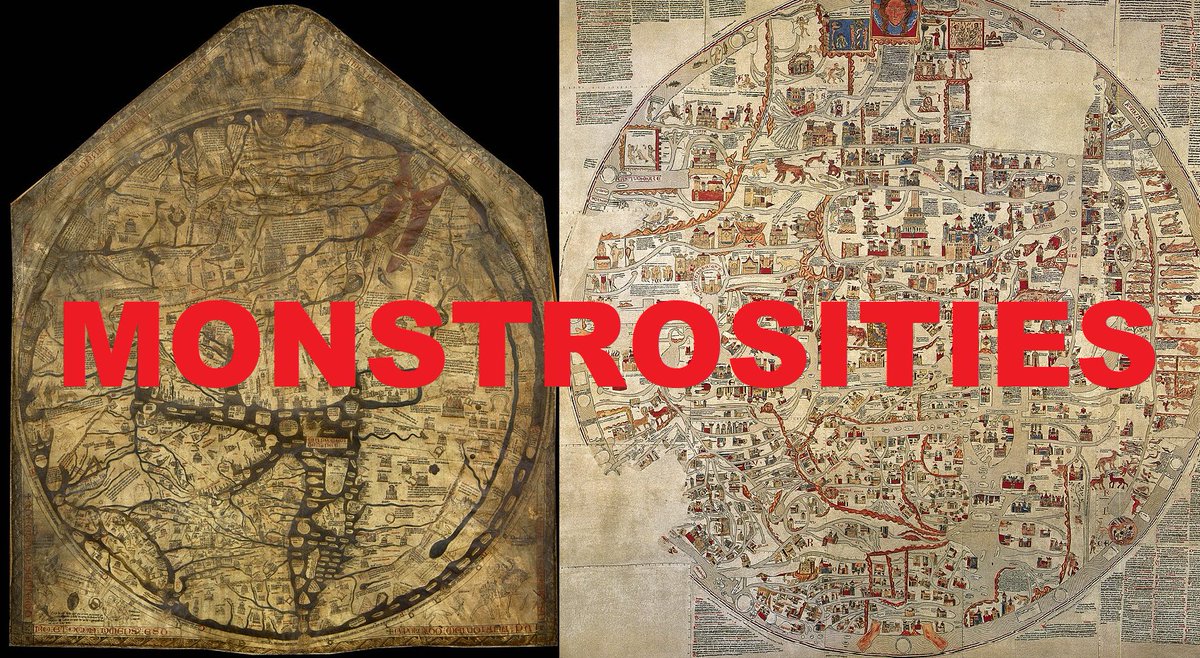

Indulge me, if you will, in some musings on the term and its implications as applied to the Hereford Mappamundi (c.1300).

(Thread - 1/1)

Indulge me, if you will, in some musings on the term and its implications as applied to the Hereford Mappamundi (c.1300).

(Thread - 1/1)

As a term, it’s meant to evoke the maps' wealth of information about geography, peoples, history, God, animals and myth.

I wonder, though, how far it’s a hasty overcorrection to older scholarship, such as Beazley's 1906 description of the Hereford & Ebstorf maps as...

(2/11)

I wonder, though, how far it’s a hasty overcorrection to older scholarship, such as Beazley's 1906 description of the Hereford & Ebstorf maps as...

(2/11)

Of course, correction of this old line of thinking is important. "Different looking maps" does not equal "bad maps with silly ignorant Dark Age makers". We should never lose sight of these as awe-inspiring, sophisticated reservoirs of contemporary knowledge of the world

(3/11)

(3/11)

BUT the rush to describe medieval mappaemundi as 'encyclopaedic' maybe goes too far in the other direction, conflating their desire to show *lots* with a desire to show *everything*. We need to read between the lines, explore what these fonts of knowledge don't cover.

(4/11)

(4/11)

I think we mustn't let terms like 'encyclopaedic' get in the way of the fact that these maps leave a great deal out. More specifically, I'm interested in what the maps omit which they could conceivably have included. What are these silences saying? What are they doing?

(5/11)

(5/11)

I focus on Asia on mappaemundi so we'll dwell there for the rest of this little thread. It just so happens to be an area which is particularly rich in pointed absences and deafening in important silences. These silences remove contemporary importance from the region

(6/11)

(6/11)

An immediately noticeable omission is the Mongols. This map was made maybe fifty years after the Mongols invaded Europe and became widely known and feared. Information had been circulating. They're not on the map - this silence renders Asia strictly as a historical space

(7/11)

(7/11)

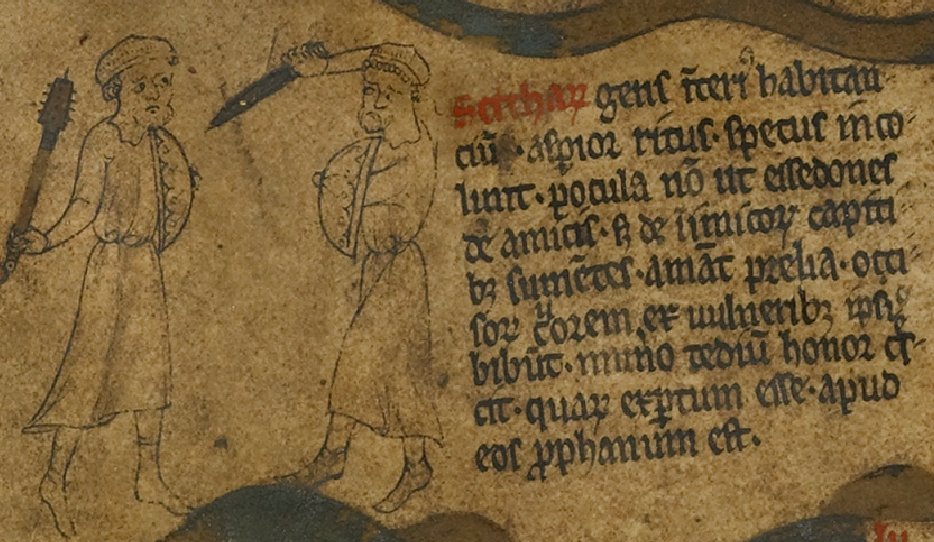

The Mongols are maybe mapped thematically by some Scythian proxies, similarly nomadic 'barbarians' from the steppes. Hereford's Scythians are the fiercest examples of the map's source, Solinus. Interesting but tame Scythians are left out. Scythia is designed to be savage.

(8/11)

(8/11)

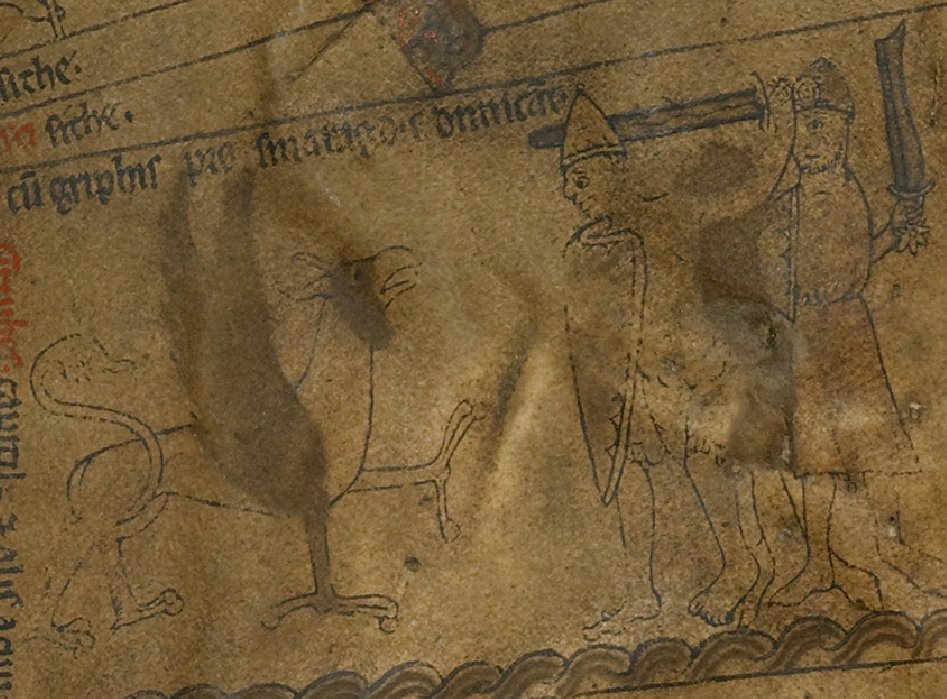

Another striking absence is the legendary Christian king in Asia, Prester John. Much evidence suggests he was both widely known of and expected in Asia - 13thC travellers looked for him and found, seemingly, his line. He's not on any mappamundi until the early 14thC

(9/11)

(9/11)

John's omission removes a strong civilisation from Asia. Similarly, the map's Asia has notably fewer cities than both the densely urban Europe and the often wealthy and sophisticated Asia of classical texts. Cities marked civilisation and order - their absence matters.

(10/11)

(10/11)

The map's Asia is an uncivilised backwater, regressive morally & temporally. But this didn't emerge from faithful encyclopaedic replication of all available knowledge, a desire to list all possible information. It is, instead, a product of strategic silence & omission.

(11/11)

(11/11)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter