Petticoats, crinolines and bustles: what did women wear under their dresses in the XIX century? : A THREAD

Petticoats, crinolines and bustles: what did women wear under their dresses in the XIX century? : A THREAD

A crinoline is a stiff or structured petticoat designed to hold out a woman's skirt, popular at various times since the mid-19th century.

In form and function these hoop skirts were similar to the 16th- and 17th-century farthingale and to 18th-century panniers, in that they too enabled skirts to spread even wider and more fully.

As the ideas associated with the French Revolution spread across Europe, a backlash against the elaborate rituals and fashions of the French court emerged.

Dresses modeled on the classical Greek form increasingly replaced the wide hoop skirts associated with Marie Antoinette and her courtiers.

This simpler fashion was seen as reflecting the more democratic ideals associated with the French and even American revolutions.

The name crinoline is often described as a combination of the Latin word crinis ("hair") and/or the French word crin ("horsehair"); with the Latin word linum ("thread" or "flax," which was used to make linen), describing the materials used in the original textile.

This fabric made its first appearance in fashion in the 1830s when it was used in women’s petticoats to support and shape the growing length and diameter of the early Victorian dress.

Often a petticoat of this stiffened fabric was worn with up to six starched petticoats in an attempt to achieve the big skirt effect; these tangling petticoats were heavy, bulky and generally uncomfortable.

One alternative to horsehair crinoline was the quilted petticoat stuffed with down or feathers, such as that reportedly worn in 1842 by Lady Aylesbury. However, quilted skirts were not widely produced until the early 1850s.

In about 1849, it was possible to buy stiffened and corded cotton fabric for making petticoats, marketed as 'crinoline,' and designed as a substitute for the horsehair textile.

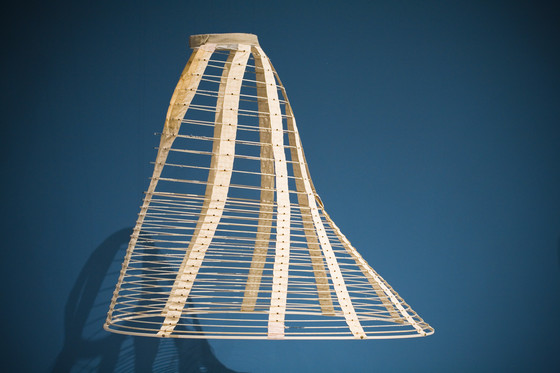

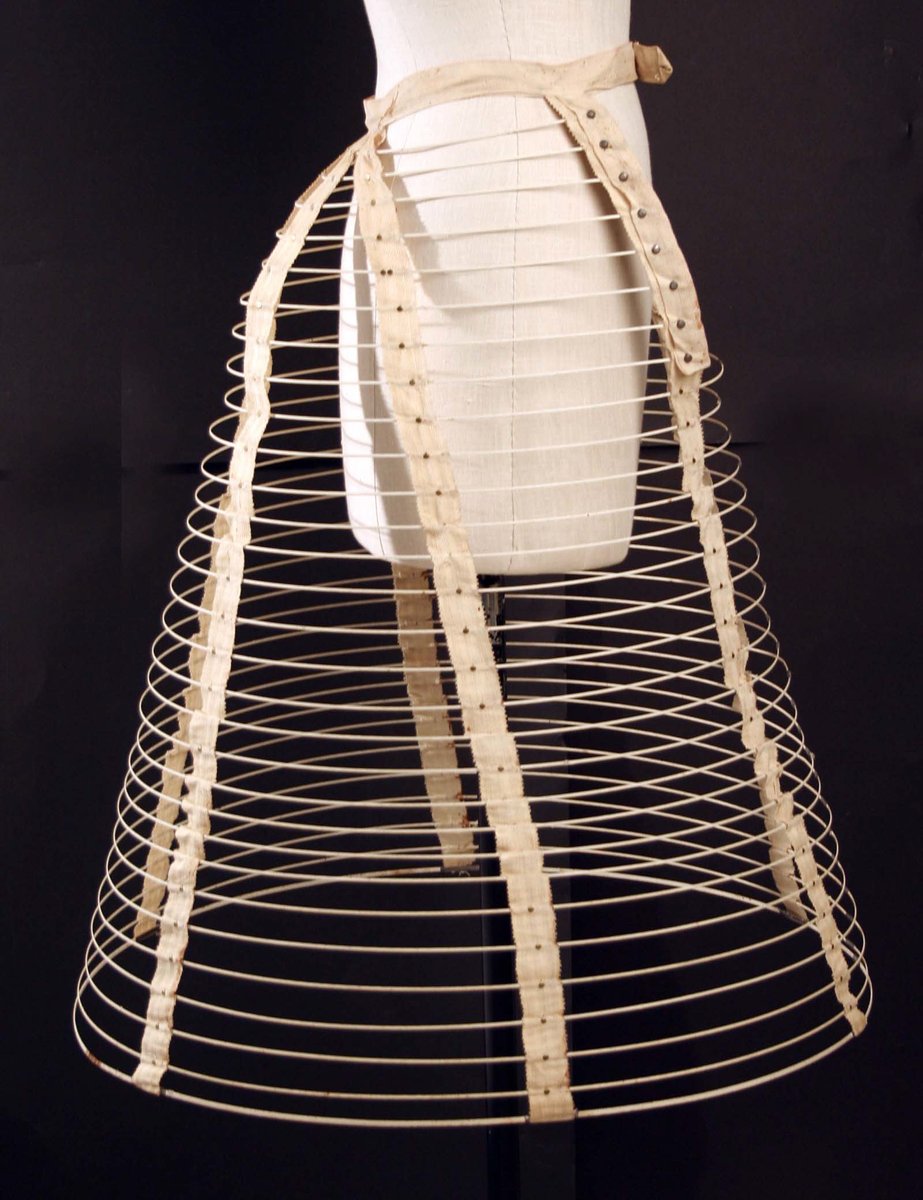

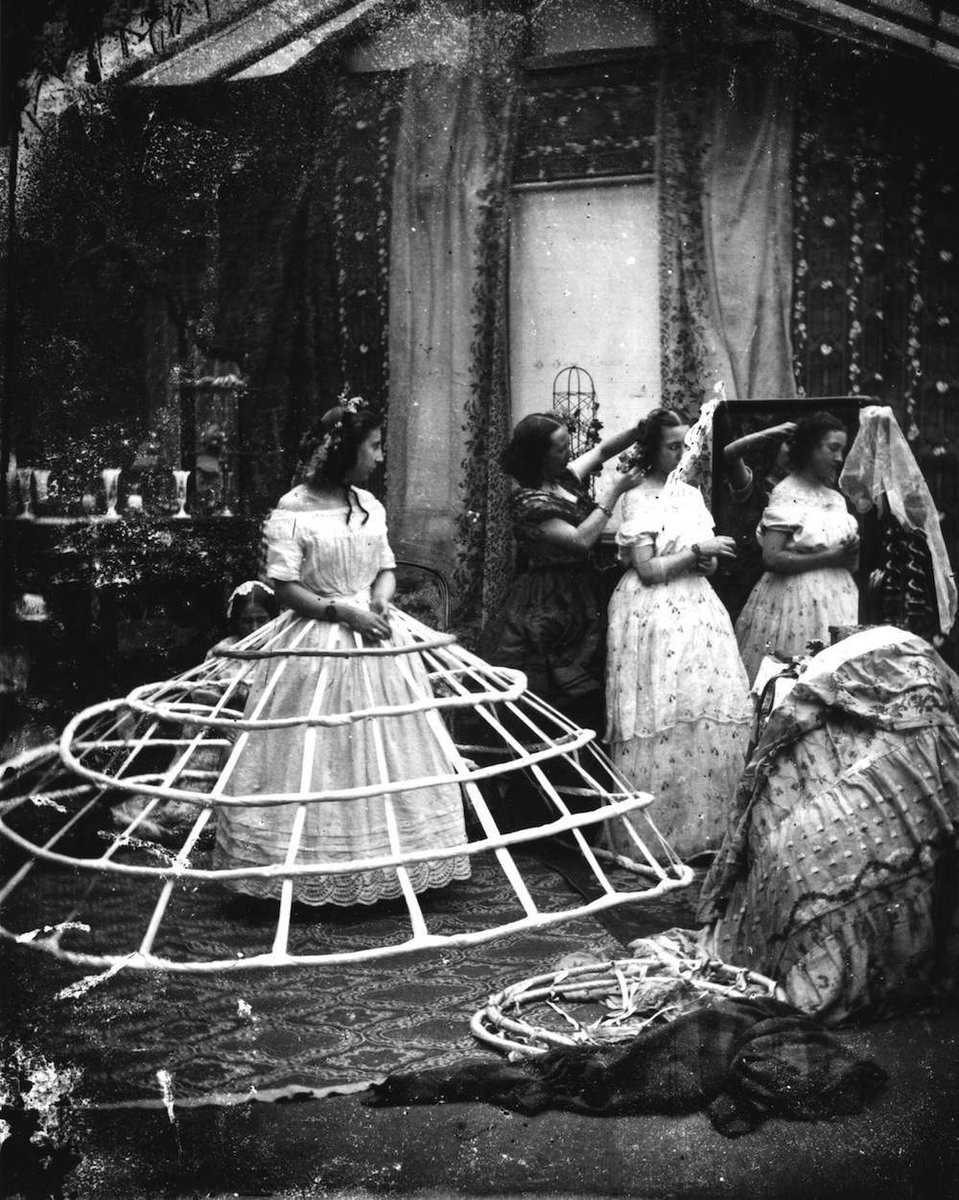

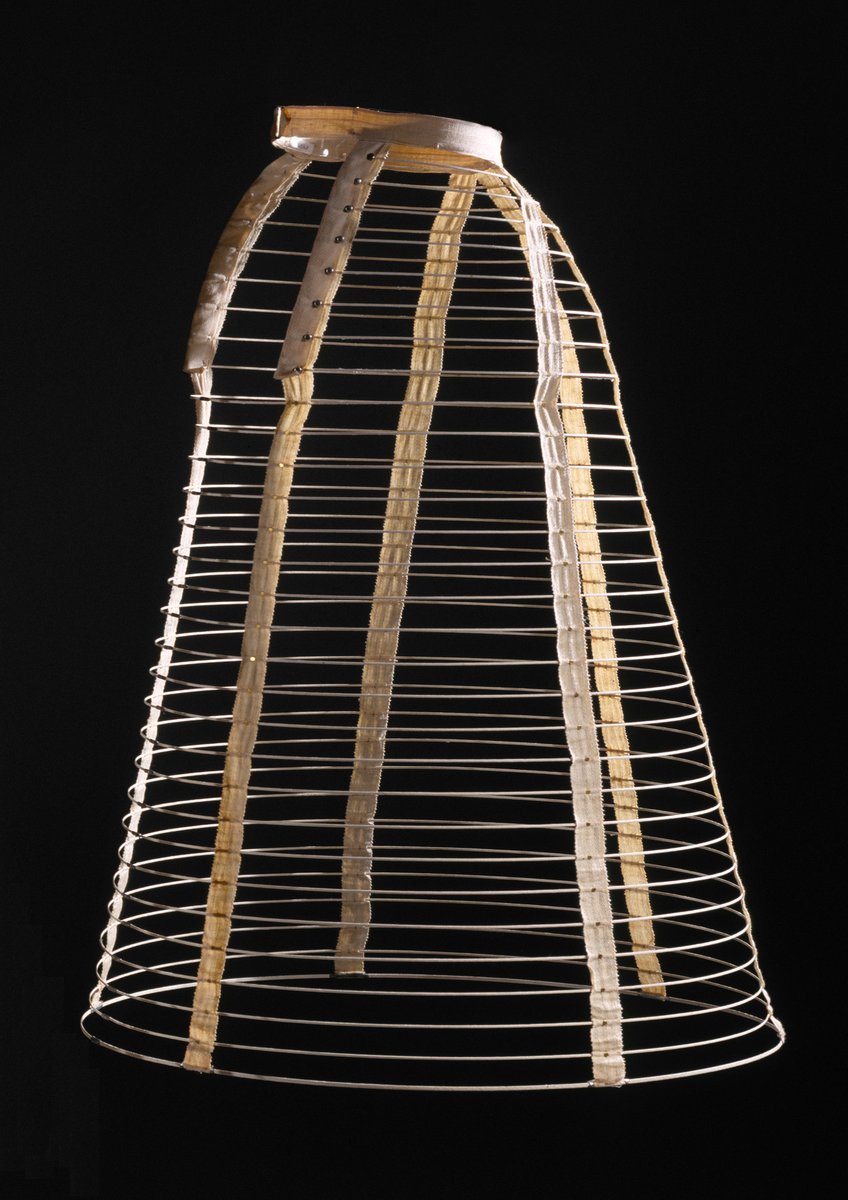

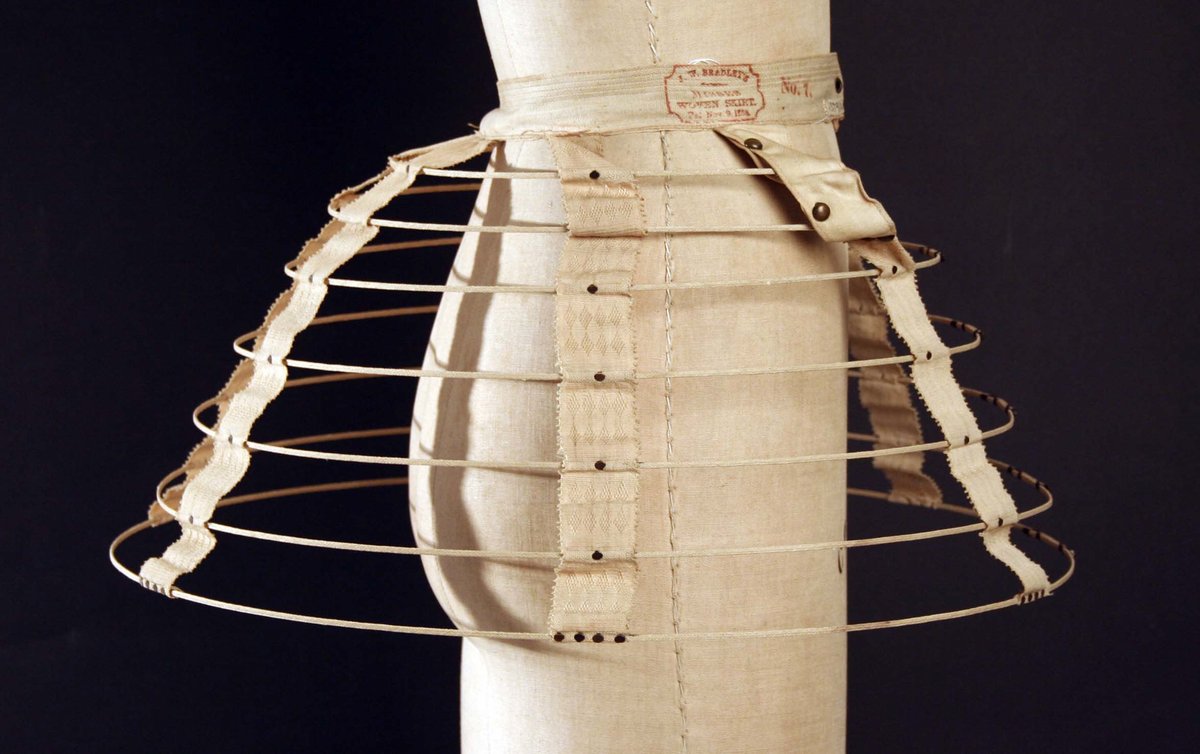

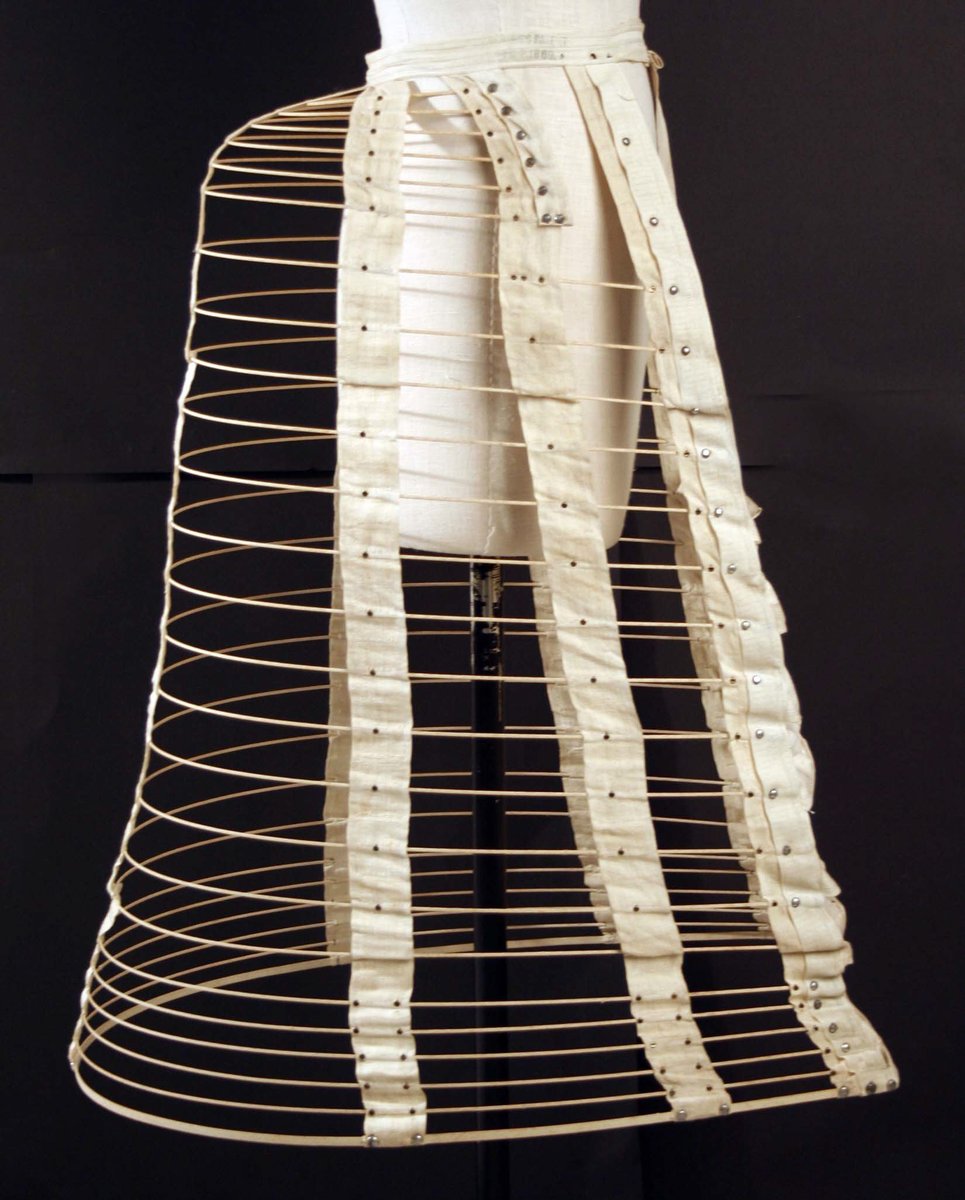

The cage crinoline made out of spring steel wire was first introduced in the 1850s, with the earliest British patent for a metal crinoline (described as a 'skeleton petticoat of steel springs fastened to tape.') granted in July 1856.

This crinoline, which was basically a metal petticoat or cage with hoops, was easier to wear than the layers of starched petticoats.

Following its introduction, the women's rights advocate Amelia Bloomer felt that her concerns about the hampering nature of multiple petticoats had been resolved, and dropped dress reform as an issue.

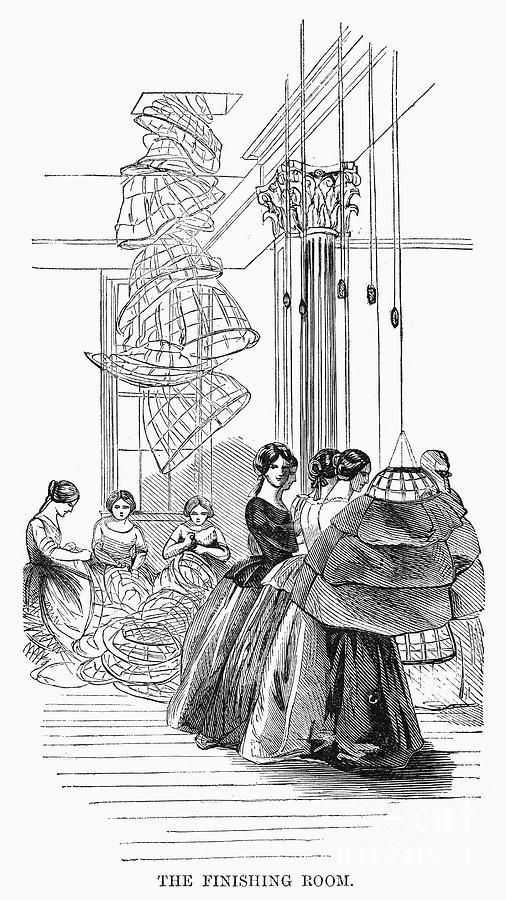

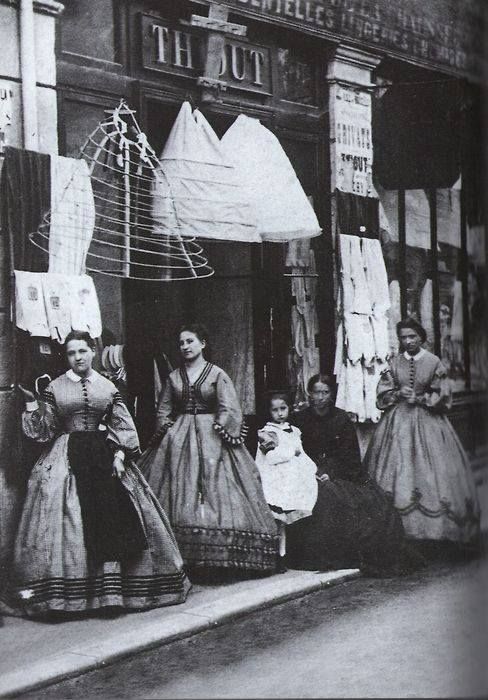

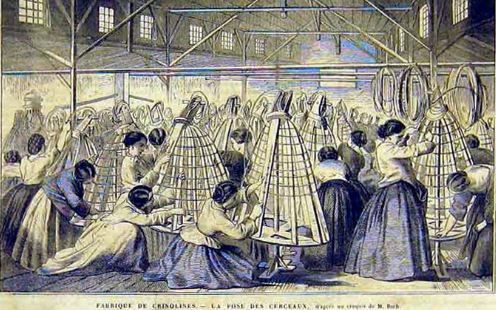

Diana de Marly, in her biography of the couturier Charles Frederick Worth noted that by 1858 there existed steel factories catering solely to crinoline manufacturers, and shops that sold nothing else but crinolines.

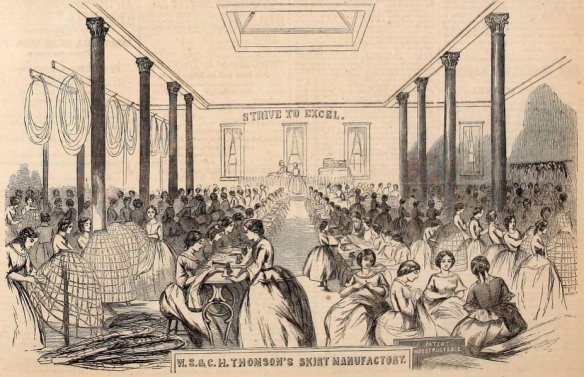

One of the most significant manufacturers of crinolines was that of Thomson & Co., founded by an American with branches across Europe and the United States.

At the height of their success, up to four thousand crinolines were produced by Thomson's London factory in a day, whilst another plant in Saxony manufactured 9.5 million crinolines over a twelve-year period.

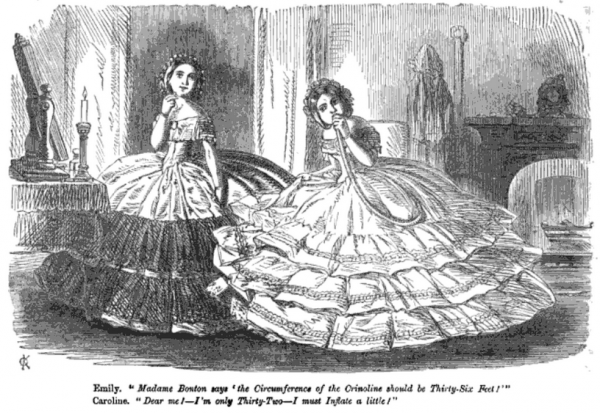

Despite some claims, such as that by the historian Max von Boehm, that the largest crinolines measured up to ten yards (30 feet) around, the photohistorian Alison Gernsheim concluded that the maximum realistic circumference was in fact between five-and-a-half and six yards.

In 1859 the New York factory, which employed about a thousand girls, used 300,000 yards of steel wire every week to produce between three and four thousand crinolines per day

while the rival Douglas & Sherwood factory in Manhattan used a ton of steel each week in manufacturing hoop skirts.

The crinoline needed to be rigid enough to support the skirts in their accustomed shape, but also flexible enough to be temporarily pressed out of shape and spring back afterwards.

Other materials used for crinolines included whalebone, gutta-percha and vulcanised caoutchouc (natural rubber).

The idea of inflatable hoops was short-lived as they were easily punctured, prone to collapse, and due to the use of brimstone in the manufacture of rubber, they smelled unpleasant.

Despite objections that the sharp points of snapped steels were hazardous, lightweight steel was clearly the most successful option.

Staged photographs showing women wearing exaggeratedly large crinolines were quite popular, such as a widely published sequence of five stereoscope views showing a woman

dressing with the assistance of several maids who require long poles to lift her dress over her head and other ingenious means of navigating her enormous hoopskirt.

Such photographs, which re-enacted contemporary caricatures rather than accurately reflecting reality, were aimed towards the voyeur's market.

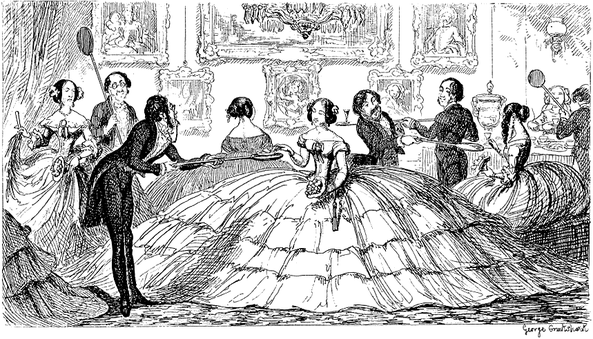

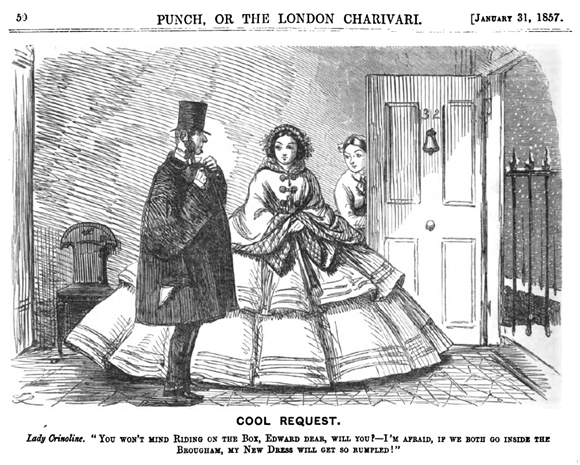

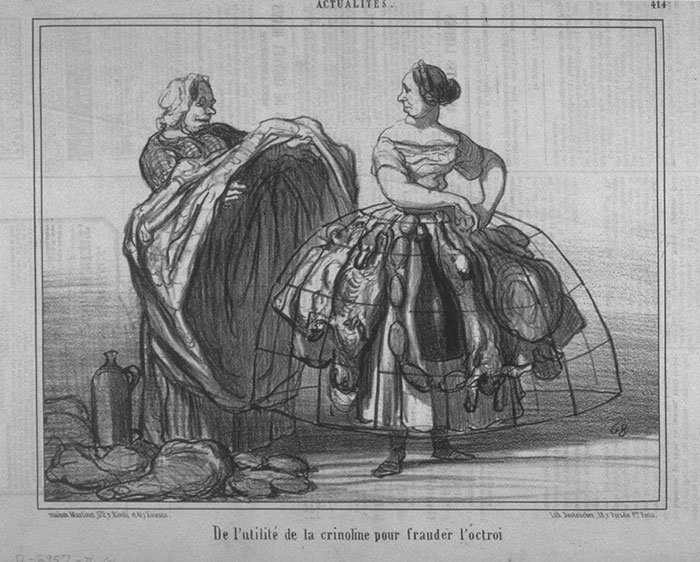

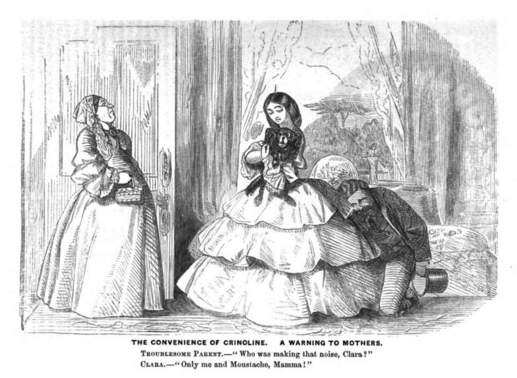

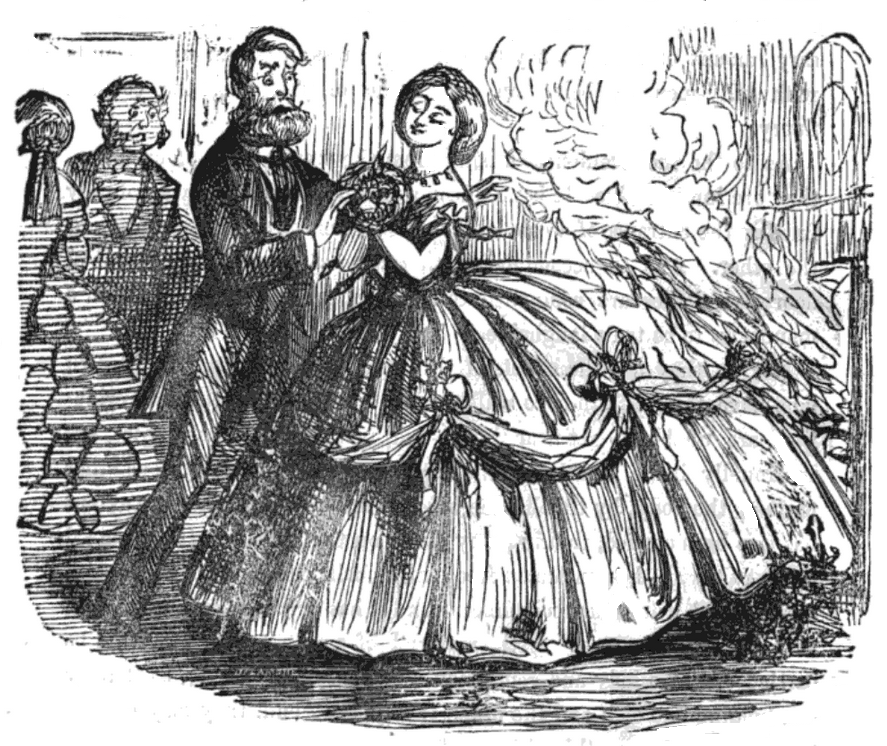

However, it was a fact that the size of the crinoline often caused difficulties in passing through doors, boarding carriages and generally moving about.

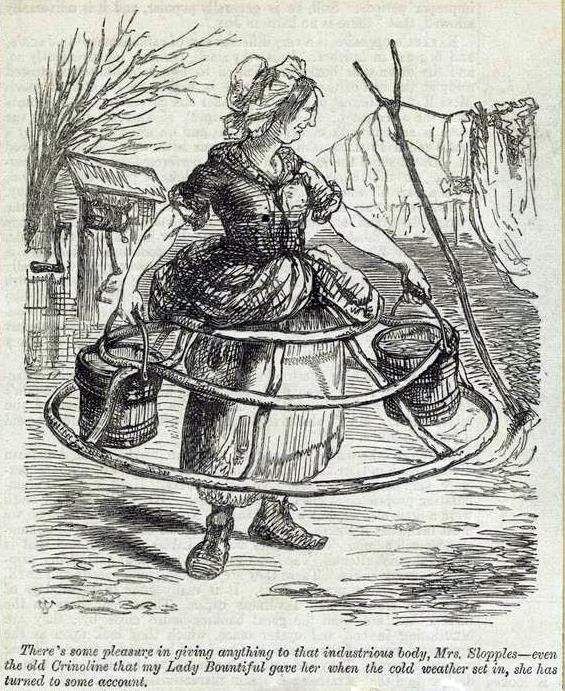

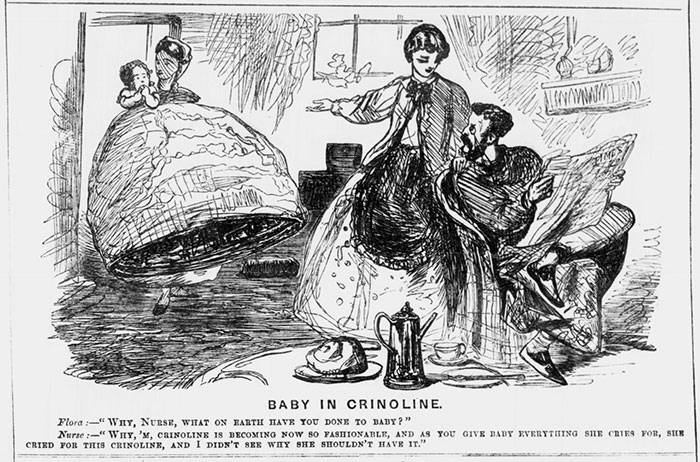

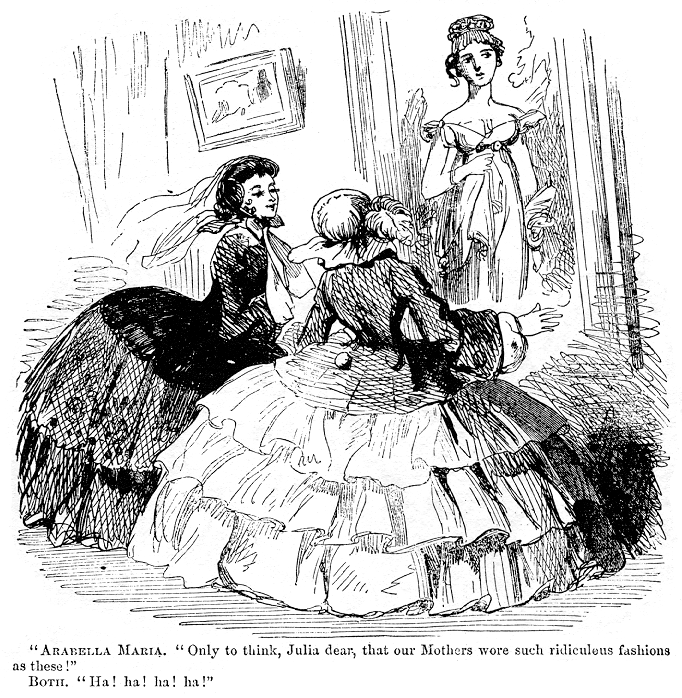

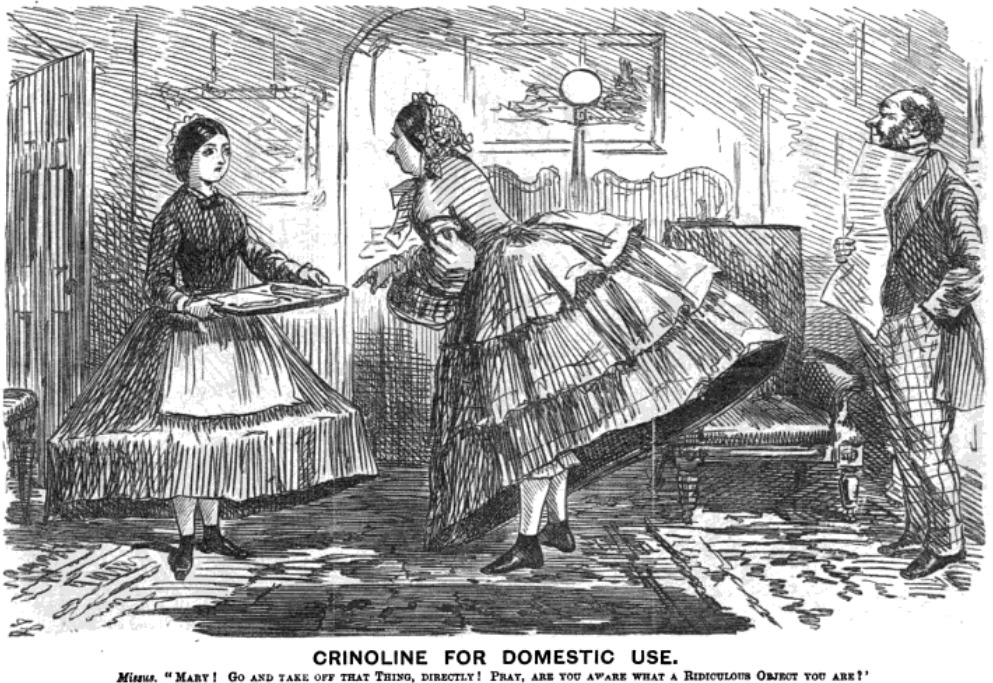

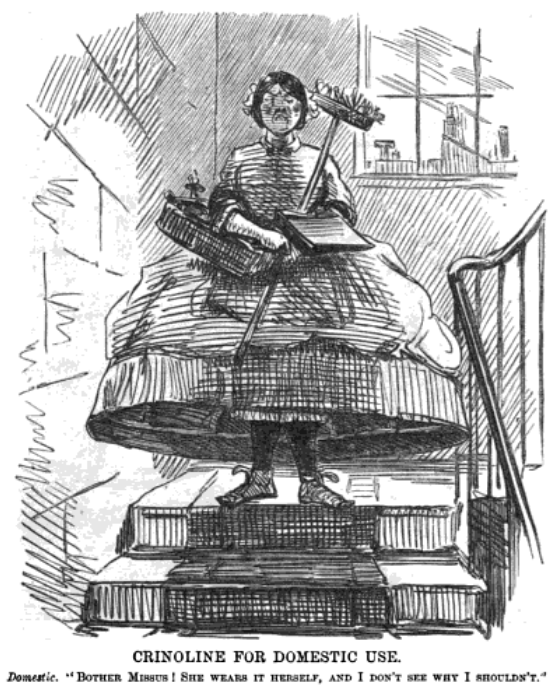

Unlike the farthingales and panniers, the crinoline was worn by women of every social class; and the fashion swiftly became the subject of intense scrutiny in Western media.

The crinoline was perceived as a signifier of social identity, with a popular subject for cartoons being that of maids wearing crinolines like their mistresses, much to the higher-class ladies' disapproval.

However, this was challenged by some servants who saw attempts to control their dress as equivalent to controlling their liberty, and refused to work for employers who tried to forbid crinolines.

The flammability of the crinoline was widely reported. It is estimated that, during the late 1850s and late 1860s in England, about 3,000 women were killed in crinoline-related fires.

Although trustworthy statistics on crinoline-related fatalities are rare, Florence Nightingale estimated that at least 630 women died from their clothes catching fire in 1863-64.

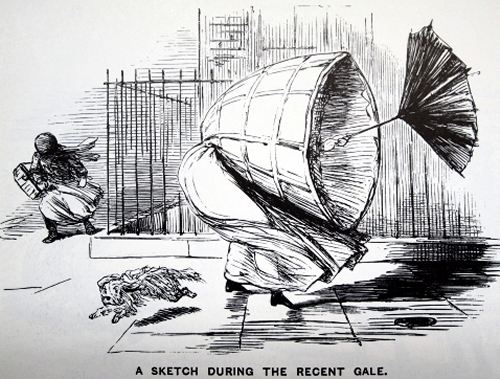

Other risks associated with the crinoline were that it could get caught in other people's feet, carriage wheels or furniture, or be caught by sudden gusts of wind, blowing the wearer off her feet.

The crinoline was worn by some factory workers, leading to the textiles firm Courtaulds instructing female employees in 1860 to leave their hoops and crinolines at home.

As the fashion for crinolines wore on, their shape changed. Instead of the large bell-like silhouette previously in vogue, they began to flatten out at the front and sides, creating more fullness at the back of the skirts (sometimes called eliptical crinolines).

By the middle of the 1860s, the dome-like shape of a women’s skirt decreased with the volume disappearing in the front and gathering at the back.

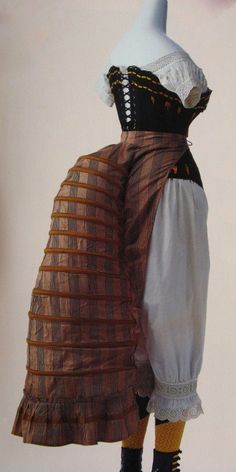

It began to fall out of fashion from about 1866. A modified version, the crinolette, was a transitional garment bridging the gap between the cage crinoline and the bustle.

Fashionable from 1867 through to the mid-1870s, the crinolette was typically composed of half-hoops, sometimes with internal lacing or ties designed to allow adjustment of fullness and shape.

Crinolettes were more restrictive than traditional crinolines, as the flat front and bulk created around the posterior made sitting down more difficult for the wearer.

The excess skirt fabric created by this alteration in shape was looped around to the back, again creating increased fullness.

Although they were conceived purely as mechanisms to achieve an aesthetic effect, crinolettes also responded to practical considerations. Some, like the Lobster-Pot crinolette, were designed, like winter petticoats of the period, to keep the wearer warm.

As with the earlier cage crinolines, sprung steel, wire and cane were used.

By 1868, the fullness of women's skirts had moved to the back, and a bustle was needed to support fashionable puffed overskirts and large sashes. The high back interest continued in the early 1870s as the bustle gradually swelled in size.

A bustle is a padded undergarment used to add fullness, or support the drapery at the back of women's dresses.

Bustles were worn under the skirt in the back, just below the waist, to keep the skirt from dragging. Heavy fabric tended to pull the back of a skirt down and flatten it.

Though the bustle was first patented in 1857, the popularity of crinoline prevented it from taking off until the 1860s.

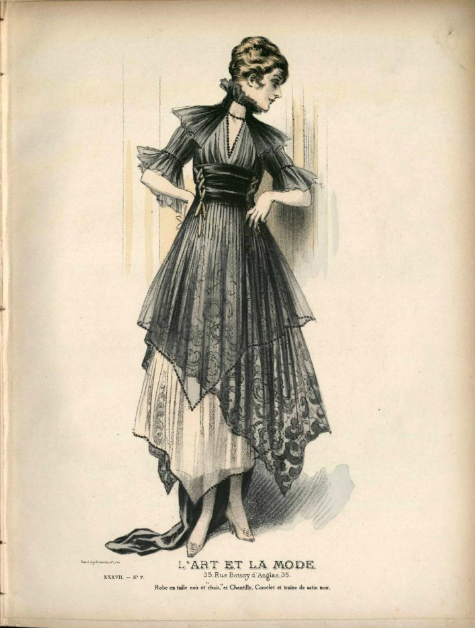

In the early stages of the fashion for the bustle, the fullness to the back of the skirts was carried quite low and often fanned out to create a train.

The transition from the voluminous crinoline-enhanced skirts of the 1850s and 1860s can be seen in the loops and gathers of fabric and trimmings worn during this period.

The bustle later evolved into a much more pronounced humped shape on the back of the skirt immediately below the waist, with the fabric of the skirts falling quite sharply to the floor, changing the shape of the silhouette.

The bustle was worn in different shapes for most of the 1870s and 1880s. The various styles of bustles were made with wires, springs, mohair padding and fabric.

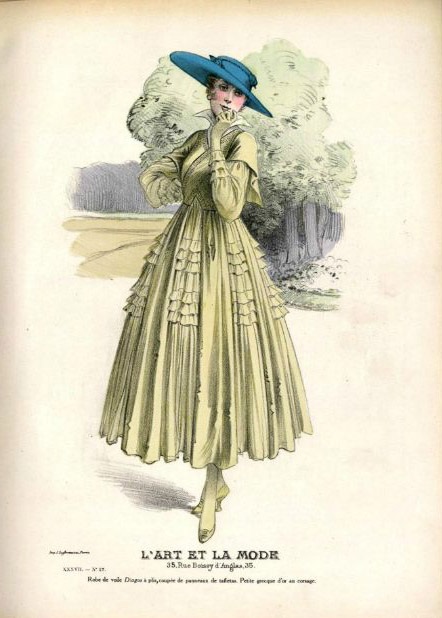

By the 1880s, the soft curve bustle dresses of the early 1870s were replaced with a new distinct silhouette featuring a severely tailored figure from the front and added draperies to the back.

Basques, pointed waists, coat bodices, and round waists with belts were all worn with the new bustle skirts; the selection of the particular style of top was made to suit the figure of the wearer.

The skirts of the early 1890s featured some back fullness, but emphasis had shifted to flared skirt hems and enormous leg-of-mutton sleeves, and bustle supports were not as fashionable.

With skirts fitting snugly to the hips and derriere in the late 1890s, however, some women relied on skirt supports to achieve a gracefully rounded hipline that set off a small waist.

While not as extreme as examples from the mid-1880s, the woven wire or quilted hip pads worn beyond the turn of century show the tenacity of the full-hipped female ideal.

The bustle had completely disappeared by 1905, as the long corset of the early 20th century was now successful in shaping the body to protrude behind.

During World War I the "war crinoline" became fashionable from 1915–1917. This style featured wide, full mid-calf length skirts, and was described as practical (for enabling freedom of walking and movement) and patriotic

In the 1950s, post-war prosperity and wealth led, in part, to the re-emergence of the crinoline and its voluminous skirts.

These voluminous skirts with their yards of excess fabric presented a sharp counterpoint to the practical skirts and clothing rations of the war years.

So let's see how the silouette changed during the XIX century!

The End

The End

Thank you for reading until the end! I hope you found this thread interesting. I've wanted to talk about crinolines and bustles since I started this account

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter