As a medievalist who sews, I am here for all of your chaperon, houppelande, and dagged-sleeve doublet needs. https://twitter.com/GoingMedieval/status/1328424904983801860

Need an embroidered coif? I GOT YOU.

It'll probably cost you $400 but I GOT YOU.

It'll probably cost you $400 but I GOT YOU.

On a semi-related note, if you sew modern clothing, studying historical tailoring--really, almost anything before like 1918--will help a lot.

When you learn modern pattern making, you're taught that there must be right angles in certain places. It's all straight lines.

Yet English tailoring remains the gold standard specifically because it's based on the philosophy of, "Show me a body that has right angles and I will draw them."

It can be easy to get stuck in stock pattern shapes. The foundation of your average top, of any kind of garment, is going to have this kind of shape:

The pieces might be more voluminous, asymmetrical, or cut up and rearranged, but this is the basic shape at the foundation of everything.

If you tailor things to fit your body, though, then take them apart, the garment you actually *wear* won't look much like that shape.

I'm trying to dig up a surviving garment to show you, but it's taking a minute, so I'll come back to this.

It's pretty hard to just draw the exact shape of your body onto fabric and get it right, if you're not a Saville Row tailor who's been drawing the same 5 patterns over and over for 40 years--

So most patterns must needs start with straight lines. That's how you got the immaculate fit when all clothes were handmade -- you basically draped each garment on the body.

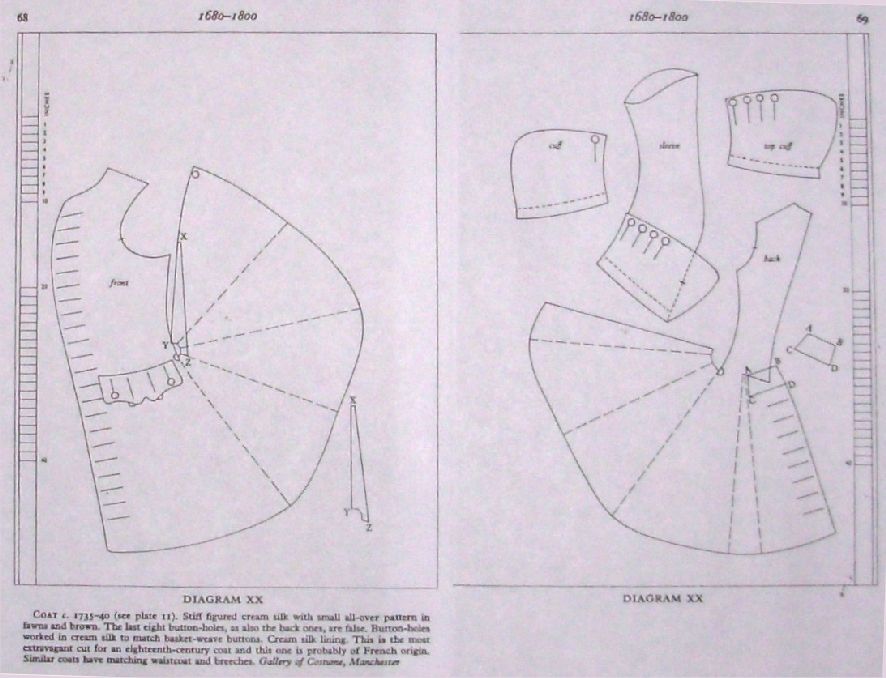

Ok, here's a 17th century coat, I think traced from a surviving garment. Familiar shape, but hardly a straight line in it!

It's pretty fun to follow the evolution of Western patterning, as they gradually come up with advanced tailoring from the experience of fitting--

And a lot of that comes after finding ways to make 14th and 15th century clothing, which was often very fitted, more economical.

Here's some late 13th century clothing, women wearing kirtles (fitted under dresses) with sideless surcoats.

We obviously can't see how the kirtles are constructed from these images, but it's the same basic idea as the surcoat--a rectangle of fabric that has been pinched onto the body. Still a pretty loose and fit, but we're inching toward princess seams.

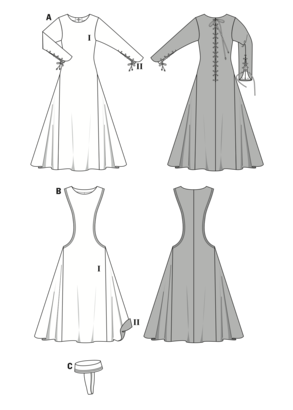

In the 14th century, the surcoat becomes passe (you start seeing it only in ceremonial portraits), so you're left with the classic, tight-bodied dress, the cotehardie.

How did they get that amazing fit? By putting on a tube made out of rectangles and triangles (economical use of fabric) and pinching, pinching, pinching.

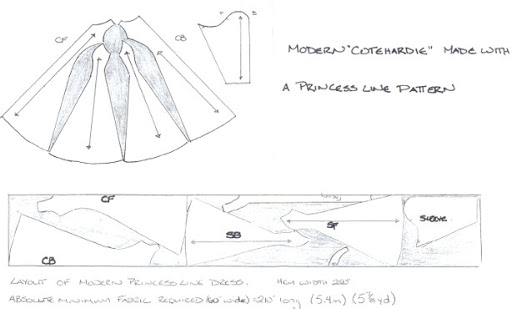

That's an adapted modern pattern, so you'll see straight lines, but in practice, all of those hourglass shapes came from pinching out straight seams between rectangles and triangles.

And this is how you get princess seams -- you had fabric milled to a particular, narrow width (something like 18"?). To fit to the body, you used 2 widths + 2 more widths, cut on the diagonal, like this.

And they used to wear that kind of as-is, resulting in the boxier, flowing shape of early medieval gowns.

But when you start pinching that thing skin tight, you end up with seams being placed where modern princess seams are, as in Dame Helen's modernized pattern:

See? Curved lines! Eventually (somewhere in the 15th century, iirc?) they saved themselves the step and starting cutting coteardies with princess seams.

Don't ask me to quote the history of the set-in sleeve (a hallmark of modern clothing), but it seems to arise the same way.

You can see in high medieval cotehardies, the sleeves are also just folded rectangles attached to a flat opening.

But you can see how the tailoring process is working toward a smaller, rounder opening, with a precisely fitted sleeve. You start seeing that as commonplace in the 17th century IIRC.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter