NEW Our paper exploring the scale of global parasite diversity is out in Proceedings B. It has a bit of everything: parasitology, biodiversity, the Smithsonian, new math, international law, and even a well-disguised fairy tale. Got a second for a story?

Our paper exploring the scale of global parasite diversity is out in Proceedings B. It has a bit of everything: parasitology, biodiversity, the Smithsonian, new math, international law, and even a well-disguised fairy tale. Got a second for a story?

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2020.1841

Our paper exploring the scale of global parasite diversity is out in Proceedings B. It has a bit of everything: parasitology, biodiversity, the Smithsonian, new math, international law, and even a well-disguised fairy tale. Got a second for a story?

Our paper exploring the scale of global parasite diversity is out in Proceedings B. It has a bit of everything: parasitology, biodiversity, the Smithsonian, new math, international law, and even a well-disguised fairy tale. Got a second for a story? https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2020.1841

I have a deep love for this one Brothers Grimm fairytale. It's a story about the nature of uncountable things, and answering impossible questions with indirect evidence. You wouldn't know it from the paper today, but our first draft was written around the outline of the story.

Our study asks three questions about uncountable things:

How do parasite species get discovered?

How do parasite species get discovered?

How many species of parasites are there on Earth?

How many species of parasites are there on Earth?

How long would it take to count each one?

How long would it take to count each one?

We turn to helminths (parasitic worms) for answers.

How do parasite species get discovered?

How do parasite species get discovered? How many species of parasites are there on Earth?

How many species of parasites are there on Earth? How long would it take to count each one?

How long would it take to count each one?We turn to helminths (parasitic worms) for answers.

We use two big datasets that museums have built over more than a century: the @NMNH National Parasite Collection, a library of close to 100,000 specimens; and the @NHM_London Host-Parasite Database, the single biggest open ecological interaction dataset.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/geb.12819

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/geb.12819

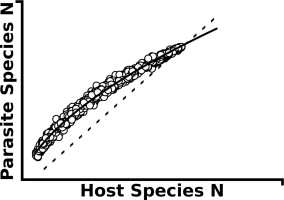

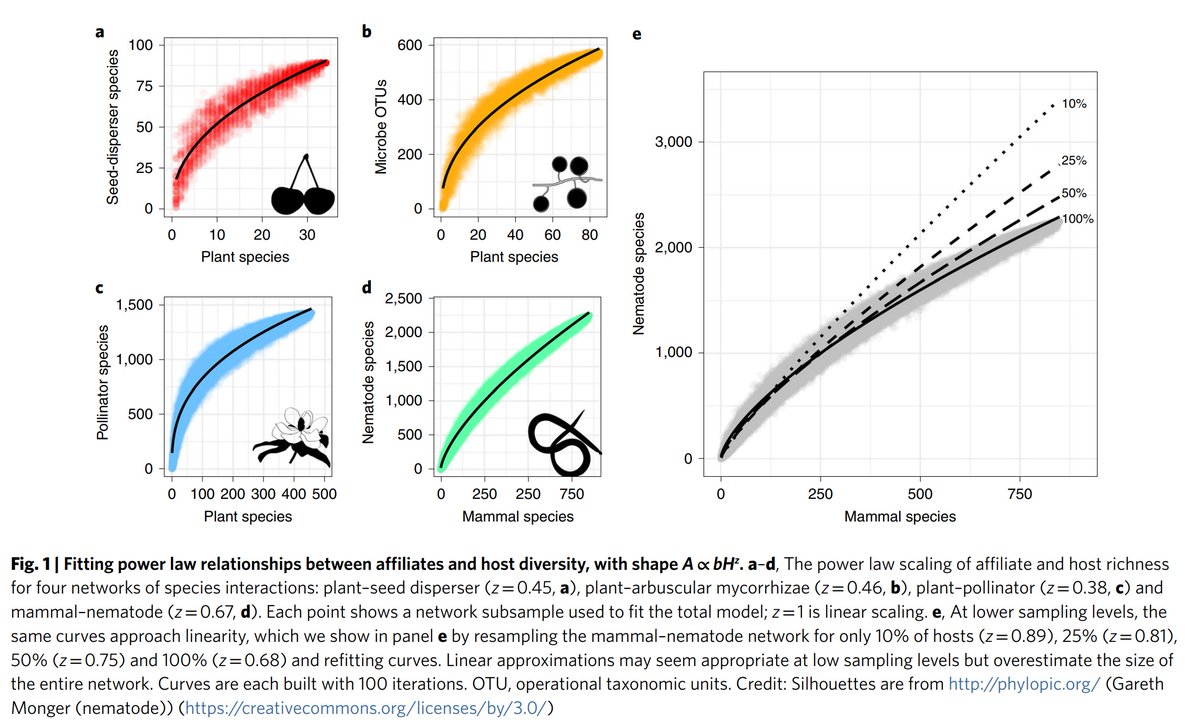

Originally, our goal was simple: re-estimate parasite diversity based on the scaling between hosts and parasites. We stumbled onto a new scaling property, only to realize @GiovanniStrona had already noticed it - with the same data - back in 2014.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0020751914000277

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0020751914000277

But it turns out the power law scaling is actually pretty common. That spun off into another paper, where we estimate the global diversity of mammal viruses (and a second one on the theory coming very soon).

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-019-0910-6

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-019-0910-6

Here, we revisited Strona's estimates, adding two new features. First, we tried to correct for "cryptic species" that are hiding in those estimates, and unlikely to be noticed without molecular data.

Second, we figured out the math to add parasite diversity across host groups:

Second, we figured out the math to add parasite diversity across host groups:

So we updated the current estimate for total diversity of parasitic worms of vertebrates, which clocks in around 100,000 species. Or, if you correct for cryptic diversity, around 350,000 potential species in total:

With those estimates in hand, we set our sights on a slightly bigger question: where are all these unrecorded species? Which species are they?

One way to answer that is "small parasites of small hosts"; body size structures which species get sampled first - and which parasites get noticed first.

Another answer is "the tropics," but probably not to the degree you expect. Parasite diversity is only intensively sampled in a handful of countries, and 90% of diversity could still be unsampled in most of the world.

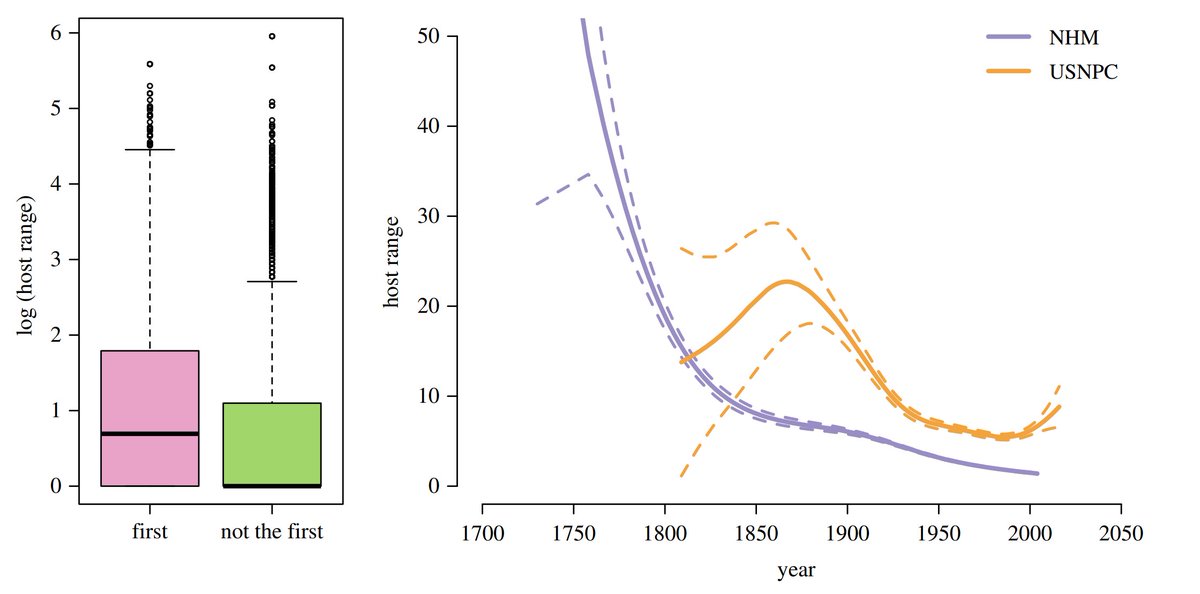

We also know missing parasites are probably mostly specialized on one or two hosts. Generalist parasites usually get noticed first - and then often revised, and separated into multiple species, once molecular data comes in.

So we have thousands upon thousands of tiny specialist parasites of tiny animals, mostly birds and fish, mostly outside of the U.S., Europe, and Australia. 85-95% of them are undescribed. What could we possibly do about that?

That brings us to the heart of this paper.

That brings us to the heart of this paper.

Both of our datasets have grown at a shockingly-steady pace since around the turn of the century. Sure, there are some dips, like World War II. But on the whole, progress on parasite taxonomy has been fairly steady.

This trend is a little bit surprising - specifically the fact it's not curving up. You might expect that the genomic revolution has sped things up, but in the data, we don't find any sort of uptick. Taxonomists are moving, on average, at the same speed now as 100 years ago.

We use that "steady rate" and our diversity estimates to come up with a back-of-the-envelope waiting time until every parasite is described.

At the current pace, that wait is about 500-700 years. If you factor in cryptic diversity, it's more like 2,000-2,700.

At the current pace, that wait is about 500-700 years. If you factor in cryptic diversity, it's more like 2,000-2,700.

Could we pull those estimates down?

Taxonomists are notoriously under-appreciated (especially parasite taxonomists). As institutions, museum collections are just as systematically under-supported.

These are bottlenecks that could be changed through collaboration and funding.

Taxonomists are notoriously under-appreciated (especially parasite taxonomists). As institutions, museum collections are just as systematically under-supported.

These are bottlenecks that could be changed through collaboration and funding.

In our study, we call that idea a "Global Parasite Project." We're not the ones creating it, and this isn't an announcement. Instead, we use it as a framework for discussing how a group of people who care about parasites could tackle the problem.

Our recommendations:

Set realistic, data-driven targets

Set realistic, data-driven targets

Fund museums and develop equitable collaborations

Fund museums and develop equitable collaborations

Build parasites into biodiversity monitoring

Build parasites into biodiversity monitoring

In the paper, we unpack each of those in more depth, including some actual governance mechanics that might help.

Set realistic, data-driven targets

Set realistic, data-driven targets Fund museums and develop equitable collaborations

Fund museums and develop equitable collaborations Build parasites into biodiversity monitoring

Build parasites into biodiversity monitoringIn the paper, we unpack each of those in more depth, including some actual governance mechanics that might help.

In our view, it's important to start thinking about a project like this sooner than later; working from only ~5% of the total sample, it's nearly impossible for us to speak confidently about parasites' macroecology, or how they'll respond to biodiversity loss and climate change.

And that's the endpoint of several long years of science. This paper was written with four of the kindest, smartest people on Earth, and it was a privilege to do science with my favorite people all in one place. Thanks @taddallas @alexandraphelan @LauraWAlexander @Annalida500

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter