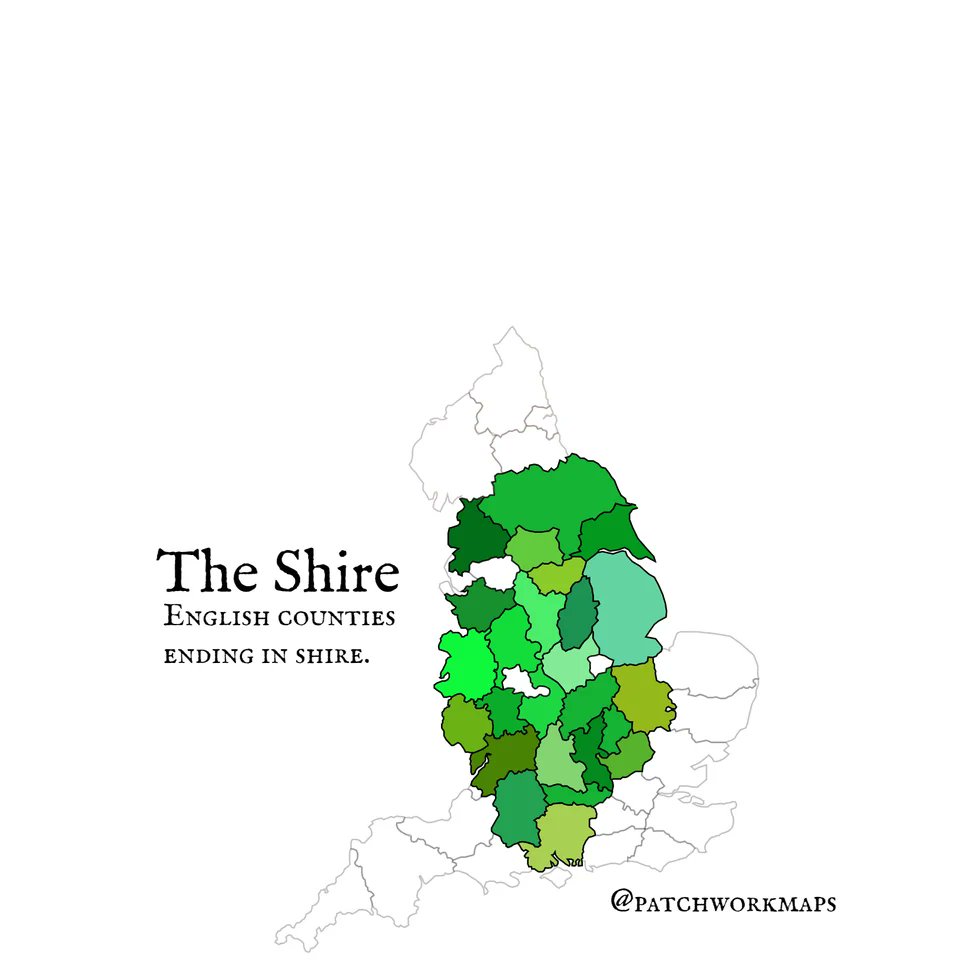

A shire is a traditional term for a division of land, found in Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand and some other English-speaking countries. It was first used in Wessex from the beginning of Anglo-Saxon settlement.

An ealdorman is a term used for a high-ranking royal official who was in charge of one or more shires.

The word ealdorman survives in modern times as alderman in many jurisdictions founded upon English law.

The word ealdorman survives in modern times as alderman in many jurisdictions founded upon English law.

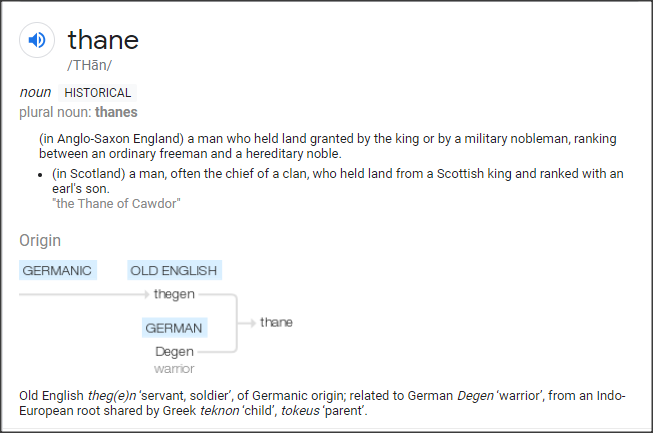

At the top of the Anglo-Saxon social order were the kings. Below them were the thanes. Thanes were powerful men who owned land and reported to the king.

The laws of the Saxons were very primitive.

For example, if you stole something you may have your hand chopped off. Murder or injury to another person was punished by a fine called the wergild.

For example, if you stole something you may have your hand chopped off. Murder or injury to another person was punished by a fine called the wergild.

Early in AD 669, two strangers arrived in England: Theodore of Tarsus, a Greek-speaking former Syrian refugee, and Hadrian, a Libyan.

Both men were monks who had fled west after the Arab conquests of the 630s.

Both men were monks who had fled west after the Arab conquests of the 630s.

Christianity had deep roots in North Africa. By the time of Hadrian’s birth in around 630-37, the region had already supplied three popes. https://www.thetablet.co.uk/blogs/1/1533/an-african-abbot-in-anglo-saxon-england

Theodore and Hadrian worked tirelessly, organizing the church across England, training priests, and imparting knowledge of Greek and Latin civilization.

Alcuin, as head of the Palatine school established by Charlemagne at Aachen, introduced the traditions of Anglo-Saxon humanism into western Europe.

He was the foremost scholar of the Carolingian Renaissance.

He was the foremost scholar of the Carolingian Renaissance.

By the time Alfred became ruler of the kingdom of Wessex in 871, that thirst for wisdom had been forced to play second fiddle to a quest for survival in the face of a Viking onslaught.

Æthelstan was the grandson of King Alfred of Wessex (reigned 871–899) and the son of King Edward the Elder (reigned 899–924).

Æthelstan was the first southern king to exercise real control over the East Midlands, East Anglia and the North, and it was around this time that the title ‘king of the English’ (‘rex Anglorum’) was first used.

It was said in the 980s that England was a land of “many different races, languages, customs and costumes”.

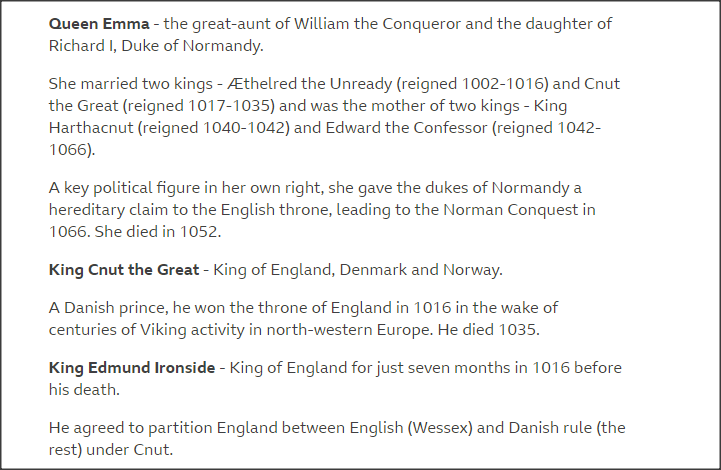

In 1002, Æthelred married Emma of Normandy.

Emma later married Cnut, and her Danish and English sons became kings.

In 1002, Æthelred married Emma of Normandy.

Emma later married Cnut, and her Danish and English sons became kings.

Emma was the mother of King Harthacnut and King Edward the Confessor. William the Conqueror claimed the throne in part through his connection to Emma.

Emma was given the English name Ælfgifu and, while Emma still appears as her name in some places, Ælfgifu is used in all official documents.

Confusingly, Æthelred’s first wife was also an Ælfgifu.

Confusingly, Æthelred’s first wife was also an Ælfgifu.

Emma and Cnut had two children together.

Gunhild became queen consort in Germany, and Harthacnut would go on to claim both the crowns of Denmark and England.

Gunhild became queen consort in Germany, and Harthacnut would go on to claim both the crowns of Denmark and England.

Myths about the Norman Conquest were very quick to develop.

Most persistent and long-standing has been the notion that independent and, most importantly, free English people were beaten down and subjected to ‘the Norman yoke’ of oppression and subjection.

Most persistent and long-standing has been the notion that independent and, most importantly, free English people were beaten down and subjected to ‘the Norman yoke’ of oppression and subjection.

After the break with Rome and later, in the time of Elizabeth, there was a lot of delving into Anglo-Saxon history to try and see what we had been like before 1066, to try to discover the character of early English law and the early English church.

All cultures make their myths from their history. This is one way of telling stories about the past, which all humans love to do.

The myth was part of the process by which English identity was kept alive in the 12th and 13th centuries to emerge with the full glory of English vernacular in the age of Chaucer in the 14th century.

By the 16th century, English vernacular was at the centre of what one might almost call a cultural big bang. This began its progress towards becoming one of the most influential languages of the world.

The way the idea of a ‘Norman Yoke’ was used in political debate must be understood in the context of the legal and constitutional issues surrounding it.

The implications of arguments based on the continuity or discontinuity of law after the Norman Conquest can be seen in debates on landownership.

The myth of a ‘Norman Yoke’ did not end with the controversies of the English Civil War.

Its traces can be identified in the writings of late 18th century liberals and republicans, such as Thomas Paine.

Its traces can be identified in the writings of late 18th century liberals and republicans, such as Thomas Paine.

By the 19th century, the myth had become associated with Victorian anti-Catholicism and Romantic Nationalism, found in literature such as Kingsley’s Hereward the Wake and Scott’s Ivanhoe.

The Anglophone farmer in the field used plain Saxon words for his livestock: cow, pig, sheep.

But by the time these animals found their way onto his Norman master’s plate, they had acquired French-derived names: beef, pork, mutton.

But by the time these animals found their way onto his Norman master’s plate, they had acquired French-derived names: beef, pork, mutton.

In Anglo-Saxon England, people could be born into slavery or they could be enslaved as a penalty for some crime.

They could be captured in war, and capturing slaves was as important a reason to go to war as capturing land was.

They could be captured in war, and capturing slaves was as important a reason to go to war as capturing land was.

In recent years, more and more English speakers have sought a gender-neutral alternative to pronouns that express the traditional male/female binary, turning either to invented pronouns like xe and zie, or to that old stand-by, singular 'they'.

They was originally a plural pronoun, borrowed by the Anglo-Saxons from Scandinavian invaders.

Shakespeare and Jane Austen used singular “they” and “their,” as was the standard in English until Victorian-era grammarians shifted course and imposed “he” above all.

Shakespeare and Jane Austen used singular “they” and “their,” as was the standard in English until Victorian-era grammarians shifted course and imposed “he” above all.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter