#CLST5 #Ethics For this #CYO4, I listened to Episode 88 of The Dirt Podcast titled Art Crimes, presented by Anna Goldfield and Amber Zambelli, which discusses heists, forgeries, and other criminal acts in the world of the arts and antiquities by looking at various sources.

In sum, the podcast is split into 3 sections: forgeries from the Museum of the Bible and the Greenhalgh family, prolific and notorious forgers, the Fälschermuseum in Vienna, and how governments in several countries are increasing their efforts to combat illegal antiquities trade.

The podcast begins by mentioning an art crime involving the Museum of the Bible, founded in 2010 by Steve Green, and intended to investigate the Bible and its impact on U.S. history and society. In March, it was discovered that the museum’s dead sea scrolls were all forgeries.

In particular, researchers found using “3D and scanning electron microscopes and microchemical testing” that the fragments, supposedly part of the Hebrew manuscript collection (Dead Sea Scrolls), were actually inscribed on leather instead of the original ancient parchment [1].

What is fascinating about the fragments’ fabrication is that parts of leather shoes from the Roman era “might have served as the substrate for some of the forgeries” [1]. A counterfeiter will often take something authentic but mundane and make them into something interesting [2].

As well, antiquities dealer Khalil Iskander Shahin and his family, in 2002, were believed to be selling ancient relics from a Switzerland vault, which is where Green obtained the forgeries. This immediately reminded me of my #CYO1 which examines the story of Heinrich Schliemann.

Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3].

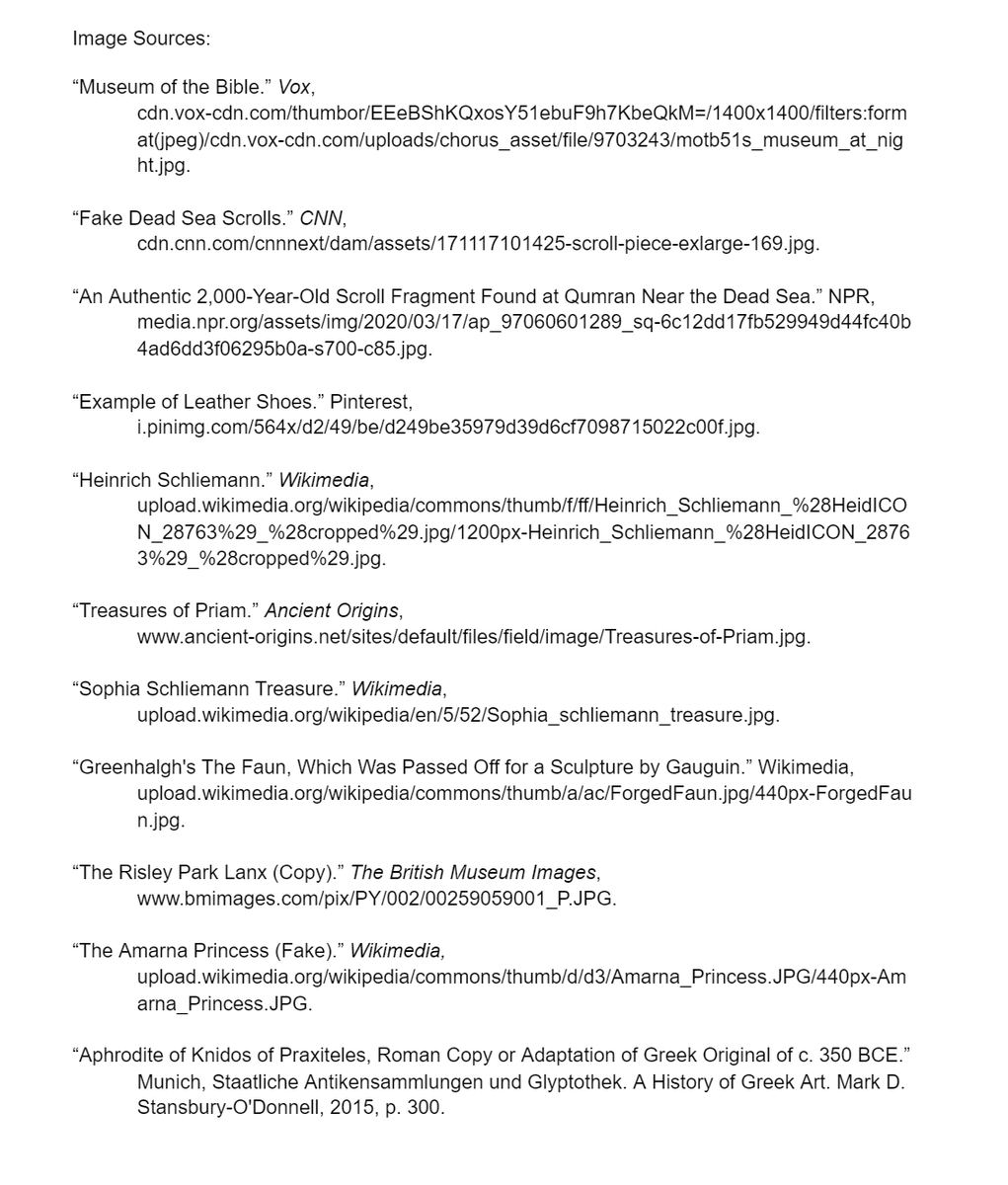

Next, we learn about the Greenhalgh family. In 2005, George Greenhalgh approached the British Museum inquiring about an Assyrian stone frieze, but upon inspection, curators noted that there was a spelling mistake in the Mesopotamian script, among other errors [3].

From 1978-2006, Shaun Greenhalgh (George’s son) created several hundred forgeries, some of which were sold to English royalty, presidents, and museums, and his technical expertise in different media was broad.

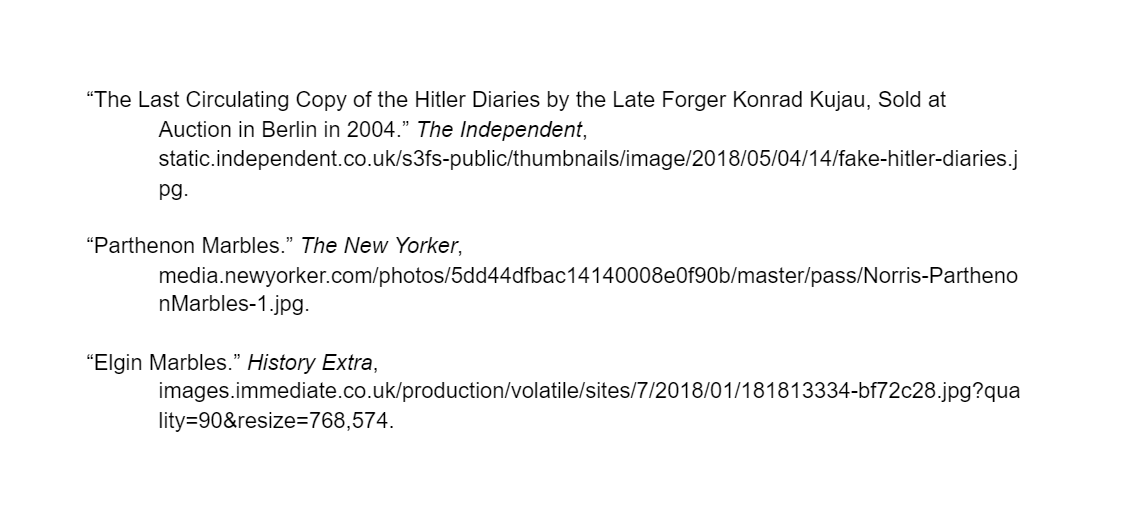

Now, it is important to distinguish between forgeries and copies.

Now, it is important to distinguish between forgeries and copies.

Copies are not necessarily forgeries, so how do we give art its value and how do we determine what has value intrinsically and what does not [2]? For instance, a painting by Michelangelo versus a copy of the painting by Shaun Greenhalgh does not hold the same intrinsic value.

Also, Roman copies of Greek originals in Classical art are common - many Roman copies were constructed using marble, whereas Greek originals utilized bronze that was melted and reused. We have seen many Roman copies in class, such as this Roman copy of Aphrodite of Knidos [4].

When Romans became “‘collectors’ and patrons of Greek art”, Greek art’s classicizing style turned into the idealizing style of Roman statues, incorporating elements of the Greek classical tradition [5]. This artifact is thus prized due to its provenance from the Classical world.

In the second section, the Fälschermuseum (museum of fake/forged art) in Vienna is introduced. One of the most interesting stories here is that of Konrad Kujau, forger of the Hitler diaries, claimed to contain a rewriting of Hitler’s biography and history of the Third Reich [6].

However, the diaries insinuated that “a surprisingly sensitive Hitler didn’t know what was happening to the Jews” and were, unsurprisingly, shortly after exposed as fakes [6].

A crucial question to ask is how exactly this massive scandal could have occurred in the first place.

A crucial question to ask is how exactly this massive scandal could have occurred in the first place.

Social psychologist Harald Welzer has stated that this scandal could only have taken place in a period of political turbulence when Germans were overly fixated on Hitler in order to “ignor[e] the fact that the German population was complicit in the horrors of the Nazi era” [6].

Finally, to address the illegal antiquities trade, governments are starting to refuse loans of their national collection artifacts that have ‘dubious’ origins. For instance, smuggled and stolen antiquities from Iraq and Syria have actually been tied to funding ISIL groups [2].

In 2017, global antiquities protectors gathered in the U.S. to learn about and share their thoughts on “stopping the black-market trade and repatriating treasures” [7]. Such discussions between countries are vital since some stolen objects may not be marketed for many years [7].

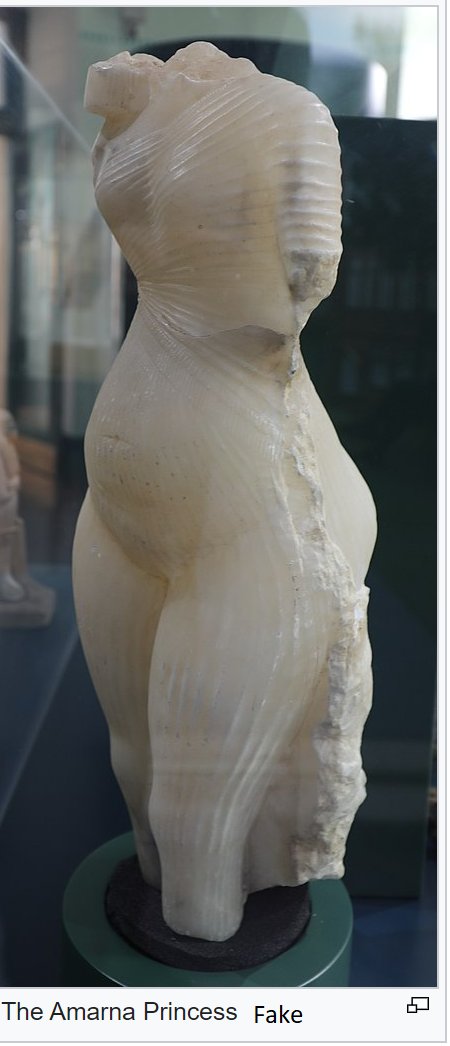

An example that demonstrates the issues and controversy surrounding repatriating treasures is the Elgin Marbles, which we have debated. Jenkins argues that “the case for repatriation along national lines tends to obscure the universal nature of great art and artefacts” [8].

Contrarily, Hanink believes Jenkins “dismisses the arguments in favor of artifact repatriation that detail the more abstract, lasting damage their (oftentimes violent) seizure caused” and that Jenkins’ perspective is that museums provide public benefit, which is what matters [9].

Overall, many adverse consequences to the aforementioned crimes have been showcased, but sometimes the roots of art crimes can be more severe, particularly with regard to the antiquities trade, such as illegal, smuggled antiquities funding ISIL, causing widespread destruction.

These examples of art crimes only barely touch upon the topics of smuggling, fraud, theft, etc. and demonstrate how these problems are still prominent in archaeology today. To fight against this, governments are becoming increasingly wary of borrowing possibly looted artifacts.

Citations:

[1] Neuman, Scott. “Museum's Collection Of Purported Dead Sea Scroll Fragments Are Fakes, Experts Say.” NPR, NPR, 17 Mar. 2020, http://www.npr.org/2020/03/17/817018416/museums-collection-of-purported-dead-sea-scroll-fragments-are-fakes-experts-say.

[2] The Dirt Podcast. “Episode 88 - Art Crimes”. The Dirt Pod. 4 May 2020. http://thedirtpod.com/episodes//episode-88-art-crimes.

[1] Neuman, Scott. “Museum's Collection Of Purported Dead Sea Scroll Fragments Are Fakes, Experts Say.” NPR, NPR, 17 Mar. 2020, http://www.npr.org/2020/03/17/817018416/museums-collection-of-purported-dead-sea-scroll-fragments-are-fakes-experts-say.

[2] The Dirt Podcast. “Episode 88 - Art Crimes”. The Dirt Pod. 4 May 2020. http://thedirtpod.com/episodes//episode-88-art-crimes.

Citations (cont.):

[3] Milmo, Cahal. “Family of Forgers Fooled Art World with Array of Finely Crafted Fakes.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 17 Nov. 2007, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/family-of-forgers-fooled-art-world-with-array-of-finely-crafted-fakes-400718.html.

[4] "A History of Greek Art." Mark D. Stansbury-O'Donnell, 2015, p. 300.

[3] Milmo, Cahal. “Family of Forgers Fooled Art World with Array of Finely Crafted Fakes.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 17 Nov. 2007, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/family-of-forgers-fooled-art-world-with-array-of-finely-crafted-fakes-400718.html.

[4] "A History of Greek Art." Mark D. Stansbury-O'Donnell, 2015, p. 300.

Citations (cont. 2):

[5] "A History of Greek Art." Mark D. Stansbury-O'Donnell, 2015, p. 385.

[6] McGrane, Sally. “Diary of the Hitler Diary Hoax.” The New Yorker, 25 Apr. 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/diary-of-the-hitler-diary-hoax.

[5] "A History of Greek Art." Mark D. Stansbury-O'Donnell, 2015, p. 385.

[6] McGrane, Sally. “Diary of the Hitler Diary Hoax.” The New Yorker, 25 Apr. 2013, http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/diary-of-the-hitler-diary-hoax.

Citations (cont. 3):

[7] Connell, Christopher. “Sharing Ideas on Black-Market Antiquities Trade.” ShareAmerica, 8 Aug. 2017, http://share.america.gov/sharing-ideas-on-black-market-antiquities-trade/.

[7] Connell, Christopher. “Sharing Ideas on Black-Market Antiquities Trade.” ShareAmerica, 8 Aug. 2017, http://share.america.gov/sharing-ideas-on-black-market-antiquities-trade/.

Citations (cont. 4):

[8] “Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums - And Why They Should Stay There.” Tiffany Jenkins, 2016, p. 217.

[8] “Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums - And Why They Should Stay There.” Tiffany Jenkins, 2016, p. 217.

Citations (cont. 5):

[9] Hanink, Johanna. “Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums…and Why They Should Stay There (Bryn Mawr Classical Review).” Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 6 Dec. 2016, http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2016/2016.12.06 .

[9] Hanink, Johanna. “Keeping Their Marbles: How the Treasures of the Past Ended Up in Museums…and Why They Should Stay There (Bryn Mawr Classical Review).” Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 6 Dec. 2016, http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2016/2016.12.06 .

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![In particular, researchers found using “3D and scanning electron microscopes and microchemical testing” that the fragments, supposedly part of the Hebrew manuscript collection (Dead Sea Scrolls), were actually inscribed on leather instead of the original ancient parchment [1]. In particular, researchers found using “3D and scanning electron microscopes and microchemical testing” that the fragments, supposedly part of the Hebrew manuscript collection (Dead Sea Scrolls), were actually inscribed on leather instead of the original ancient parchment [1].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4D7iEXEAEeeC6.jpg)

![In particular, researchers found using “3D and scanning electron microscopes and microchemical testing” that the fragments, supposedly part of the Hebrew manuscript collection (Dead Sea Scrolls), were actually inscribed on leather instead of the original ancient parchment [1]. In particular, researchers found using “3D and scanning electron microscopes and microchemical testing” that the fragments, supposedly part of the Hebrew manuscript collection (Dead Sea Scrolls), were actually inscribed on leather instead of the original ancient parchment [1].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4D9APWMAExdP2.png)

![What is fascinating about the fragments’ fabrication is that parts of leather shoes from the Roman era “might have served as the substrate for some of the forgeries” [1]. A counterfeiter will often take something authentic but mundane and make them into something interesting [2]. What is fascinating about the fragments’ fabrication is that parts of leather shoes from the Roman era “might have served as the substrate for some of the forgeries” [1]. A counterfeiter will often take something authentic but mundane and make them into something interesting [2].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4EeTQXcAYTe4s.jpg)

![Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3]. Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4EyUEWEAAPdhx.jpg)

![Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3]. Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4E1ldXYAUQjzF.jpg)

![Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3]. Following Schliemann’s find of “Priam’s Treasure”, the Turkish government sued him, inciting him to smuggle the treasure (which remains internationally disputed) out of Turkey; throughout history, there have been many instances of art crimes with long-lasting consequences [3].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4E5lRXUAMTmDL.jpg)

![Also, Roman copies of Greek originals in Classical art are common - many Roman copies were constructed using marble, whereas Greek originals utilized bronze that was melted and reused. We have seen many Roman copies in class, such as this Roman copy of Aphrodite of Knidos [4]. Also, Roman copies of Greek originals in Classical art are common - many Roman copies were constructed using marble, whereas Greek originals utilized bronze that was melted and reused. We have seen many Roman copies in class, such as this Roman copy of Aphrodite of Knidos [4].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4HcgkXcAAwD-3.jpg)

![In the second section, the Fälschermuseum (museum of fake/forged art) in Vienna is introduced. One of the most interesting stories here is that of Konrad Kujau, forger of the Hitler diaries, claimed to contain a rewriting of Hitler’s biography and history of the Third Reich [6]. In the second section, the Fälschermuseum (museum of fake/forged art) in Vienna is introduced. One of the most interesting stories here is that of Konrad Kujau, forger of the Hitler diaries, claimed to contain a rewriting of Hitler’s biography and history of the Third Reich [6].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4Hto2XYAAY8qV.jpg)

![An example that demonstrates the issues and controversy surrounding repatriating treasures is the Elgin Marbles, which we have debated. Jenkins argues that “the case for repatriation along national lines tends to obscure the universal nature of great art and artefacts” [8]. An example that demonstrates the issues and controversy surrounding repatriating treasures is the Elgin Marbles, which we have debated. Jenkins argues that “the case for repatriation along national lines tends to obscure the universal nature of great art and artefacts” [8].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4H5erWEAEsPHV.jpg)

![An example that demonstrates the issues and controversy surrounding repatriating treasures is the Elgin Marbles, which we have debated. Jenkins argues that “the case for repatriation along national lines tends to obscure the universal nature of great art and artefacts” [8]. An example that demonstrates the issues and controversy surrounding repatriating treasures is the Elgin Marbles, which we have debated. Jenkins argues that “the case for repatriation along national lines tends to obscure the universal nature of great art and artefacts” [8].](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/Em4H62TXMAAuOY7.jpg)