So, this is another preparatory thread for my massive War of the Spanish Succession thread. Today I’ll be covering a bit of the background of 18th century warfare and the main differences between the armies of the various combatants.

A lot of this information has also been covered in previous threads, but I wanted to compile that divided information into one spot. For information on why war was fought in this manner check out my first thread. https://twitter.com/JasonLHughes/status/1305247314538385416?s=20

Alright, so as mentioned in that first thread, the most common infantry weapon in the 18th century was the flintlock musket, which was capable of firing around 2-3 rounds a minute (thought that rate of fire would drop off over time).

In battle, infantry regiments were usually drawn up in long lines about 3 ranks deep (the French and Austrians often deployed in 4 or 5 ranks instead). Dense columns were generally only used to get troops to the battlefield. Massed columns were rarely used as a battle formation.

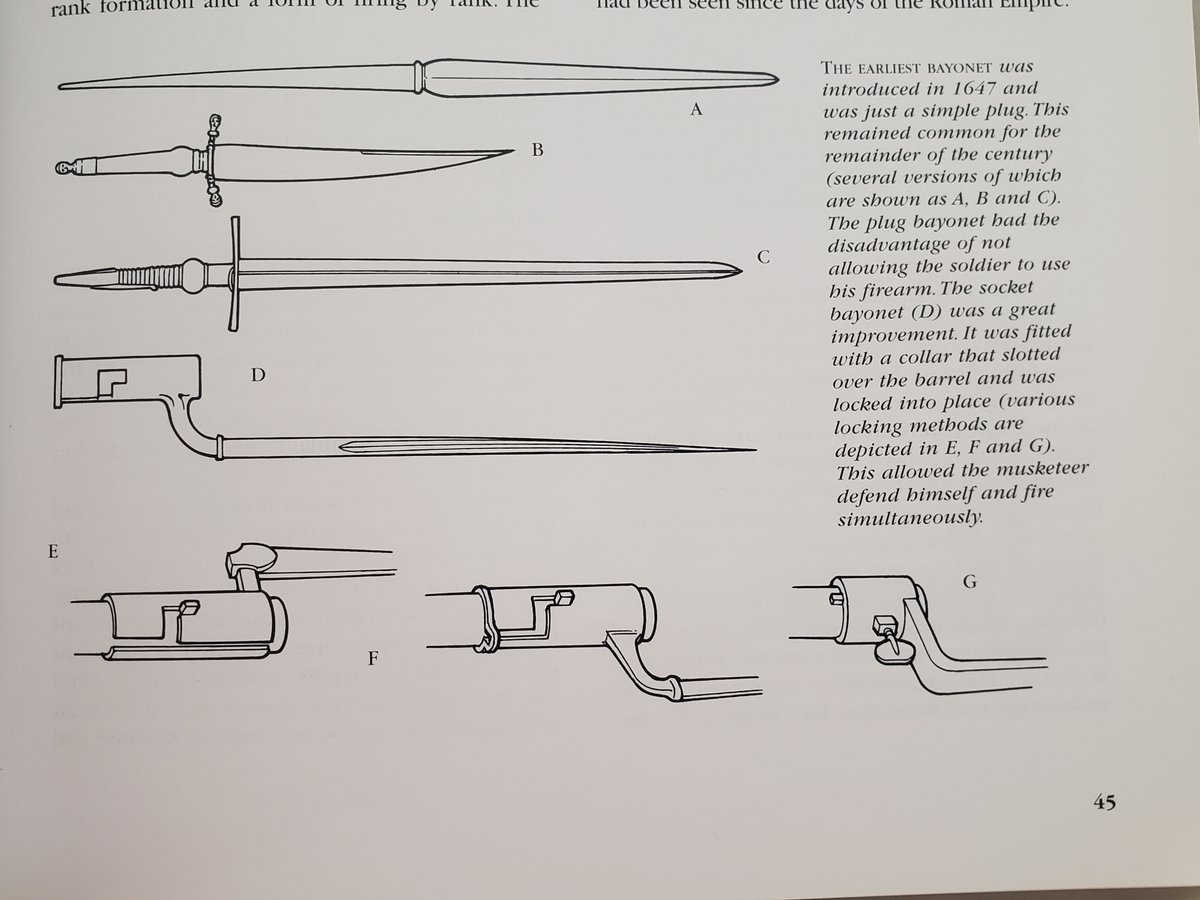

Ring/socket bayonets were finally in widespread use, which made the pike practically obsolete and gave musketmen some sturdiness against melee attacks, particularly from cavalry. However, bayonet charges were still relatively rare and most combat was done at range.

There were doctrinal differences between the different combatants revolving around firing drills. While these differences might seem marginal at first glance, they actually led to French inferiority in the prolonged firefights that generally defined infantry contests.

French soldiers still fired by rank, with the first rank discharging a volley, then lying (or crouching) down to allow the second rank to fire and so on. A slightly superior variant had the first ranks preemptively lower themselves and had the rear ranks fire first.

This method allowed men to reload immediately after firing, which was not possible in the first variant mentioned due to the extreme difficulties of reloading from a kneeling or prone position. However, this form of firing was still not continuous or consistent.

As mentioned earlier, French battalions formed up in four or five ranks with each man directly behind the other, which meant that only the first three ranks could fire at once, with a fourth to two fifths of the battalion’s muskets going unused. The Austrians used the same drill.

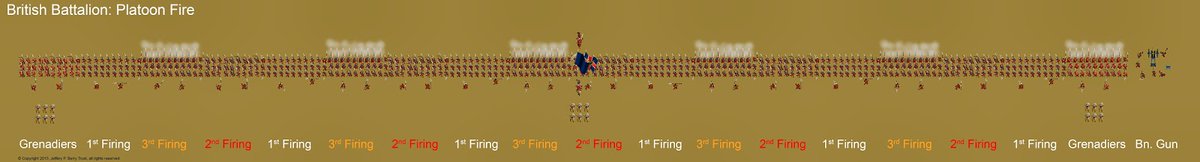

A vastly superior fire drill was practiced by the Anglo-Dutch forces, who fired by platoon. Basically, the battalion was subdivided into platoons that (supervised by officers) would alternate their order of firing in order to maintain a nearly uninterrupted wall of lead.

Platoon firing allowed for a more rapid rate of fire over time than firing by ranks and had a more severe impact on enemy morale due to the fire’s consistency. This, combined with forming up in only three ranks, meant that Anglo-Dutch battalions maximized their firepower.

French battalions also just took up far more space than their opponents. They still maintained an unnecessary amount of space between both their ranks and files, which meant that their more densely packed opponents could pack more firepower into a smaller frontage with less men.

This all is not to say that the French infantry was bad. It wasn’t. The Guard, Swiss, Scottish, and Irish infantry regiments were of exceptional quality. The rank of file was generally brave and stood their ground as long as could be expected. Unfortunately, it was rarely enough.

While cavalry was not as dominant as it had been during the Middle Ages, it was still an essential element of any army. While infantrymen could create a break in enemy lines, they could not exploit it. Cavalry was vital to making a victory decisive and leading the pursuit.

Cavalry could also minimize a defeat by covering the withdrawal of allied infantry. In the major battles of the War of the Spanish Succession, the cavalry (which generally made up 25% of the army) was generally the key factor in determining the fate of the battle and its impact.

During the 9 Years’ War, France’s superior cavalry led to success in most of the war’s major engagements. Its cavalry’s superiority came from its elan rather than its fine tactics or horses (which were generally inferior in quality to English, Dutch, and Danish horses).

The aura of invincibility surrounding French cavalry would be shattered during the War of the Spanish Succession. French cavalry relied on an initial discharge of pistols before closing with the enemy at a trot. This was basically a compromise between shock and fire doctrines.

This wouldn’t have been a problem if other powers had continued to imitate French doctrine as they had for decades. However, Marlborough transformed Anglo-Dutch cavalry into a force that relied almost solely on shock and the arme blanche (the cold steel).

It should be noted that Anglo-Dutch cavalry did not do hell-for-leather charges. Anglo-Dutch cavalry maintained the line and advanced at a fast trot rather than a gallop. Its superiority over the French cavalry came from the uninterrupted nature of its attack, not its speed.

Marlborough also kept an unusually large amount of cavalry in reserve, which allowed him to react to the fluid flow of battle and exploit the opportunities created by his excellent infantry. Marlborough also emphasized the necessity of infantry support for his cavalry.

Against other foes the French cavalry did exceptionally well, and it still performed bravely against Marlborough’s cavalry. However, French elan could do little against a better organized and led foe. France was not let down by its men, but by its (political) leadership.

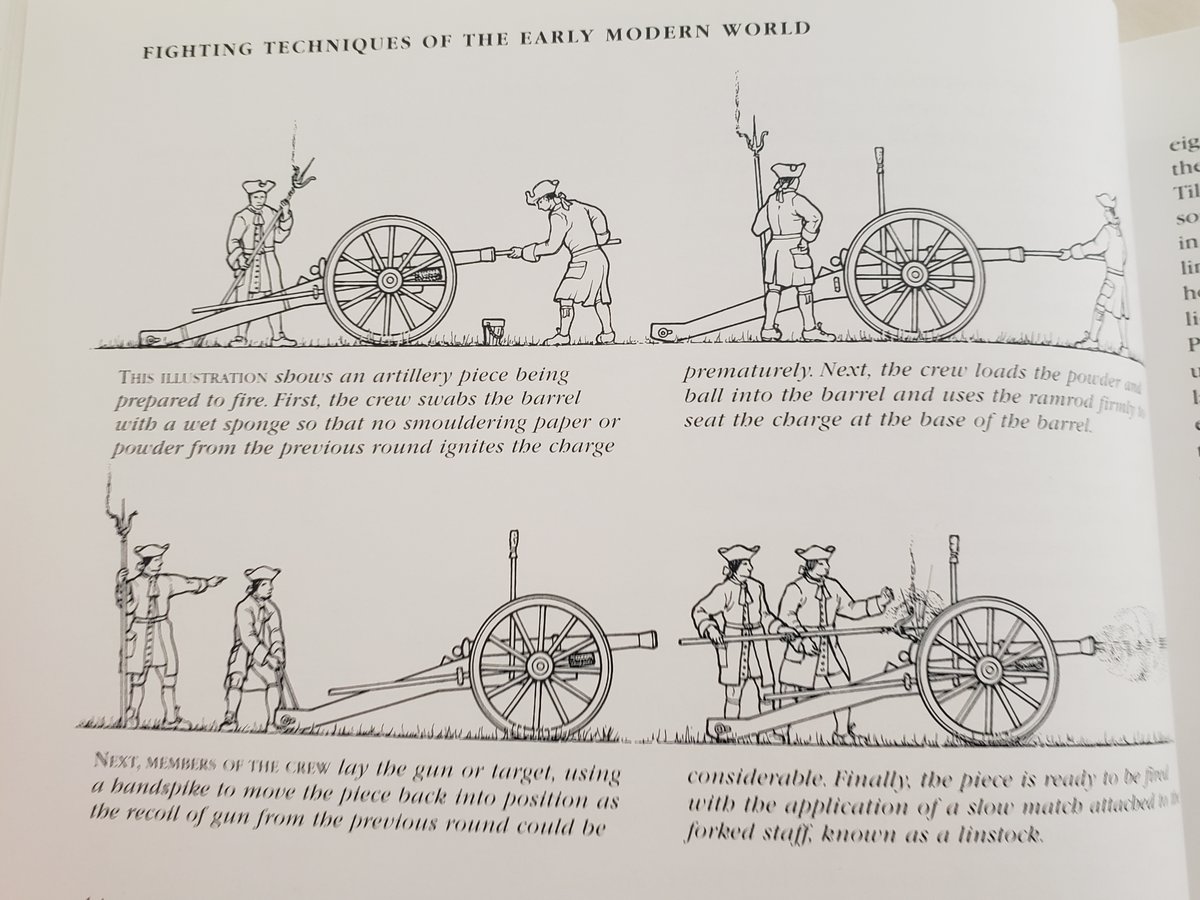

The artillery arm differed little between armies. Anglo-Dutch forces generally attached small field pieces to their infantry battalions, but the ratio of 1 artillery piece for every 1,000 men was still fairly consistent across most armies (though it did vary by theater).

The actual quality of artillery was fairly consistent across armies. Its performance more relied on the ability of the army’s commander to bring the guns into action and place them properly. The effectiveness of an army’s artillery was often a question of logistics.

Logistics during the War of the Spanish Succession was a nightmare. European infrastructure was generally in poor shape, and few regions had the development to support large armies for any period of time. Armies relied upon massive supply networks to maintain themselves.

The mere act of moving a sizeable army was difficult, much less moving that army with speed. Wagons filled with vital supplies clogged small roads and greatly restricted armies’ freedom of movement. Thus rapid, successful marches over even moderate distances were celebrated. Brb.

Providing adequate supplies and transporting those supplies was difficult in the best of times, it was hellish in even moderately bad weather. Thus, the campaign season generally stretched from around May (occasionally April) to roughly November to avoid snow and mud.

The French traditionally had a logistical advantage due to the extensive use of depots and a semi-efficient supply chain. Thus, they could often take to the field weeks before their enemies. Marlborough was one of the only commanders who could occasionally match the French tempo.

It should also be noted that these limited campaigns were rarely determined by decisive battles. The campaigns of Marlborough were exceptions, and even then, he only fought four decisive battles over about 9 years of command.

Instead, most campaigns were determined by sieges and elaborate (and often brilliant) maneuvers. Battles were risky, and only the most brilliant of the period’s commanders were willing to risk their monarch’s expensive armies on a few hours of violence.

Still, the War of the Spanish Succession had an unusually high number of dramatic and impactful battles for its time. Not until the Napoleonic Wars nearly a century later would so many talented commanders again take the field.

That should basically cover most of the information you need to follow along with my actual thread on the War of the Spanish Succession. Hopefully, I’ll be able to get that thread out in the coming days, but I’ve failed basically every timetable I’ve set for these threads lol.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter