...and here we go! Hi everyone. It's @markharrisnyc, and for the next couple of hours, I'll be livetweeting tonight's #VultureMovieClub selection, Citizen Kane, here on @vulture. We start at 7 p.m. ET--you can rent or stream it almost anywhere, including YouTube...

Feel free to ask questions along the way if you've got them; I'll try to get to as many as I can. Meanwhile, here's a very short background piece on the movie for first-timers that you can read in the 5 minutes before we start. https://www.vulture.com/2020/11/how-to-watch-citizen-kane-before-watching-mank-on-netflix.html

And we're off! You'll notice that the only credit you see at the start of the movie is "A Mercury Production by Orson Welles." What was Mercury? The theater company that Welles and John Houseman had founded in NYC four years earlier, with a number of actors you'll see in Kane.

RIght away, Welles is playing with movie conventions--in this case horror--that audiences in 1941 knew inside and out. Left: Kane. Right: Frankenstein.

"Rosebud" is our first glimpse of old Welles, and an early example of how you think you'll look when you're old vs. how you actually end up looking.

"Xanadu" is meant to be San Simeon, now known as Hearst Castle; it was the 90,000-square-foot home of William Randolph Hearst, build on a private plot of land that was 82,000 acres, more than one-tenth the size of Rhode Island.

The identification of Kane as the "greatest newspaper tycoon of this or any other era" would have made him instantly recognizable to 1941 audiences as Hearst.

Welles's playful use of an extended newsreel to set up Citizen Kane is all the more subversive when you consider that audiences would literally have just finished watching a straightfaced newsreel five minutes earlier. The animated map of the US was, in '41, pretty innovative.

The interviewer talking to Kane in the newsreel sequence when he returns from Europe is played by Gregg Toland, one of the all-time great cinematographers, who shot Citizen Kane and The Best Years of Our Lives.

In case you were wondering how long it was going to take this live-tweet to get to the word "clitoris," the answer is: 13 minutes. So let's dig into the question of whether "Rosebud" was, in fact, a dirty joke--screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz's use of Hearst's rumored pet name...

...for a part of the anatomy of his longtime mistress Marion Davies, who is brutally travestied, in part, as Kane's second wife Susan Alexander, the character you're now meeting. The rumor seems to have gained steam in 1989...

...when Gore Vidal made mention of it in an essay in The New York Review of Books. One reader raised the reasonable question: How would he know? https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1989/08/17/rosebud/

(We'll come back to Rosebud later.) We're getting pretty deep into the movie now, and it's worth noting that we've still only met Kane indirectly--on his deathbed, in a newsreel, in the accounts of others, and now in old files. It's one of cinema's great buildups.

Kane as a little boy is one of the film's most famous sustained shots--no cutting for a really long time, during which little Charles goes from being the focus to a small, oblivious figure in a frame within the frame.

"Merry Christmas....and a Happy New Year" is one of the most elegant 18-year time jumps in all of cinema.

Twenty-five minutes in and we finally meet Welles as Kane in a straightforward, surprisingly unassuming scene, sitting at a desk. It still feels momentous given the elegance of the buildup.

Kane's "You provide the prose poems, I'll provide the war" is a direct lift of something Hearst is said to have told the artist Frederic Remington about the Cuban revolution in 1987: "You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."

“At the rate of a million dollars a year, I’ll have to close this place…in sixty years.” Welles giving off strong BDE (Bezos Debt Energy) in this scene.

Welles was only 24 when he directed Citizen Kane. To prepare, he watched one Hollywood movie as many as forty times: John Ford's Stagecoach. It was another Ford movie, How Green Was My Valley, that eventually clobbered Kane at the Oscars in early 1942.

Welles never won an Oscar for directing. Kane's editor, however, won two Best Director Academy Awards--Robert Wise went on to direct West Side Story and The Sound of Music. "When he was doing Kane," Wise said of Welles, "it seemed to be his whole life."

"Are you still eating?" "I'm still hungry." These newspaper scenes are the trimmest you'll ever see Welles, who was already self-conscious about his size. He used diet pills to shed weight and a back brace and lifts to look taller and leaner.

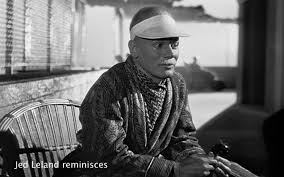

That's the great Joseph Cotten as Jed Leland (both young and old). Two years later, he would have the role of his career in Alfred Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt.

This growth-of-a-newspaper montage blends music, images, and dialogue so beautifully, and choosing to make the last "note" of the music an exploding flashbulb is a dazzlingly brash Welles touch.

Hearst was known as the "Great Accumulator"--the collection of statues you see cluttered together as a result of Kane's European spending spree foreshadows some of the bleakness later in the movie, images of a man overwhelmed by possessions.

The scene in which we see Jed Leland reminiscing in the hospital as an old man anticipates Warren Beatty's use of real-life "witnesses" forty years later in his epic Reds. (Welles, incidentally, was obsessed with Beatty, not as a filmmaker but as a lothario.)

The breakfast scene--really a sequence of scenes--between Kane and his first wife was the first thing in Citizen Kane to be shot. (The movie eventually ran 21 days over schedule.)

"Mr. Bernstein is apt to pay a visit to the nursery now and then." "Does he have to?" Hollywood movies were, in 1941, just beginning to tentatively acknowledge anti-Semitism. It would have been hard to miss the import of that line, coming from an old-money WASP.

Congratulations to everyone who correctly IDed Agnes Moorehead as Kane's mother. Can you name the actress who played Kane's first wife? Here she is in Kane and, later, in her signature role.

The courtship scene between Kane and his soon-to-be-second wife Susan Alexander is one of the most simply filmed passages in the movie--almost as if Welles wanted to suggest how innocent and unadorned the relationship was at the beginning. No trickery or ornamentation.

Now onto Kane's political campaign. The huge shot of Kane in front of Kane has cast an eighty-year shadow; you can see it played with in Giant, A Face in the Crowd, Patton and countless other the man/the myth movies.

If you're wondering whether Kane's promise to jail his political opponents has uncomfortable contemporary resonanance, yeah, it does. It is my sad duty to inform you that Donald Trump claims Citizen Kane as his favorite movie.

Trump didn't get Citizen Kane, but amazingly, he does seem to have seen and remembered it. "“he had the wealth, but he didn’t have the happiness," he told Politico. >

Trump on Kane: "The table getting larger, and larger, and larger, with he and his wife getting further and further apart as he got wealthier and wealthier—perhaps I can understand that.” https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/06/donald-trump-2016-citizen-kane-213943

Welles fell down a flight of stairs in the scene in which he chases Jim Gettys--who was based on a Tammany Hall politician who ran afoul of Hearst--out of the boarding house. He chipped his ankle in two places and had to direct from a wheelchair for two weeks.

This post-election argument between Kane and Jed Leland is a great example of Welles's--really Toland's--camera-on-the-floor technique. Citizen Kane pioneered the use of high and low angles to make its main character monstrous, looming, pathetic, big and small at once.

Citizen Kane's brutally unkind treatment of "singer" Susan Alexander remains one of its most controversial aspects. The character was thought by almost everyone to be a slap at the comic actress Marion Davies, Hearst's mistress of many decades.

But Davies was not untalented, and Hearst himself may have used his papers to suggest the cruelty in an attempt to turn the public against Welles. This is an area in which David Fincher's Mank provides a lot of fresh insight. Below, Davies and Mank's Amanda Seyfried.

Earlier I tweeted that Gregg Toland was the interviewer in the newsreel sequence. I'm not sure I'm right about that; he may be the (faceless) interviewer who questions Jed Leland in the hospital.

Dorothy Comingore gives such a poignant, human performance as Susan Alexander Kane. Her own subsequent story is heartbreaking; she was blacklisted as a Communist, possibly at Hearst's urging, and never made another movie after 1951.

If Citizen Kane survived only as a GIF, it would be this one.

“You have to hate the camera and regard it as a detestable machine because it should be doing better than what it can do….You have to whip it through the movie and not approach it on your knees.” --Orson Welles #vulturemovieclub

There's a myth that Citizen Kane was rejected or scorned when it opened. In fact, the New York Times' new critic Bosley Crowther wrote that “it comes close to being the most sensational film ever made in Hollywood. Count on Mr. Welles; he doesn’t do things by halves.” But...

...Crowther didn't really like the story. What can you do? Critics gonna critic. (Just kidding: I am officially pro critics doing criticing.)

When did Citizen Kane first get designated as the best American film of all time? The answer seems to be sometime in the 1950s. In a 1952 poll of critics for the magazine Sight and Sound, it was tied for 13th with Grand Illusion and The Grapes of Wrath. But by 1962...

...Citizen Kane had ascended to the top slot, a position it held again in 1972, 1982, 1992, and 2002 (the poll is conducted every ten years). In 2012, it finally fell to second place, behind this movie.

That same year, Citizen Kane finished third in a poll of directors, behind Tokyo Story and 2001. (Welles himself participated in a directors' poll in 1952. His choice for the greatest film of all time: Charlie Chaplin's City Lights.)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter