Greetings all and welcome to part 3: "But I don't want any of that, I'd rather... I'd rather, just, sing!"

Part 1: https://twitter.com/EvanSchultheis/status/1326642087480217601

Part 2: https://twitter.com/EvanSchultheis/status/1327008246192861186

Part 1: https://twitter.com/EvanSchultheis/status/1326642087480217601

Part 2: https://twitter.com/EvanSchultheis/status/1327008246192861186

Sorry here's Part 2: https://twitter.com/EvanSchultheis/status/1327008246192861186

And the reference, for those who don't get it:

I'm going to start this thread again picking up where we left off last night after a discussion with @mikeaztec28, on the probable development of the role of Spatharokoubikoularios in the early 5th century (which I had mostly thought was an Anastasian development).

Spatharioi (Spatharii in Latin in this period) started out in the courts as formal bodyguards before it became an honorific title in the middle Byzantine period. Spatharioi were allowed to have weapons in the presence of the emperor, and could be soldiers or eunuchs.

Chrysaphius, who was very influential at Theodosius II's court, was both Praepositus Sacri Cubiculi and Spatharios. Likewise, it's possible Heraclius could have held both the titles of Primicerius Sacri Cubiculi and Spatharios, meaning he may not have had a dagger, but a Spatha.

Archaeological evidence for long daggers in the empire, as already discussed, is weak. Spatha are well evidenced though, with several mid-5th century Roman examples having been found at sites like Dijon. They also appear extensively in late Roman art.

There are many types of Spatha in the 5th century: Illerup-Whyl, Ejsbol-Sarry, Osterburken-Kemathen, Asiatic-type, etc.

The Osterburken-Kemathen-type and Asiatic-types are, to our best evidence, the ones the Romans were largely using in the 5th century.

The Osterburken-Kemathen-type and Asiatic-types are, to our best evidence, the ones the Romans were largely using in the 5th century.

This is mine, forged by Mark Green. However, you fundamentally cannot fathom how massive this thing is until you hold it in your hand.

The swords of the Spatharioi are said to be gilded and gem-encrusted. This example, from Pouan-les-Valles in France, is the earliest dated (c. 460 AD) and one of the best known-examples of the Germanic gold-hilt spathas. Any of the three figures could have had a sword like this.

The other type dominant at the time was the Asiatic-Type, spread by the Huns and Alans in the late 4th-6th centuries. Most of the examples we see in 6th century art belong to this family of swords, except with Germanic-derived scabbard fittings. This one is from Novorossijsk.

5th Century swords in art are weird, since the scabbard fittings never match the actual archaeology. They almost always show wide, semicircular, circular, or bar chapes on the end, when U-chapes and Gundremmingen-type chapes were used in the 5th century.

Case in point: the recently discovered mosaics from Huqoq, Israel, dated to c. 438 AD. The large, circular chapes here belong to a type that had mostly fallen out of use by 320 AD.

And this leads us right into Valentinian III's sword, which appears to be a mix of a blade inspired by the statue of the four Tetrarchs and fittings pretty typical of late 3rd century blades like this one from Cologne (bottom):

To look at what an Emperor's military attire looked like in the 5th century, we mostly have to look to the Diptych of Honorius, which *does* show an Eagle-hilted sword, as well as a probably Germanic-derived Spatha.

In actuality, the best researched depiction of an emperor in military attire is Stilicho's, here representing Valentinian I during his visit to Carnuntum.

Roman literary sources and art make it clear that there were very formal conventions for how the emperor appeared on campaign and in the court beginning in the early 4th century. Lydus, who details the dress of the Patrikioi and Magister Militum, also describes the Emperor.

Lydus states that the emperor wore a white Paragaudes which had a gold thread crux gammata-based pattern woven across the entirety of the tunic's body, with gold thread woven decoration (Sementa, Gonateia, Perikheiridai, and Klavoi) which would have been in the coptic style.

To see this one may simply turn to the infamous portrait of Justinian in the 6th century San Vitale. His military Khlamys was "double-folded" (oval, instead of semi-ovoid), red (Kokkos), of first-grade silk. His courtly Khlamys is not described by Lydus.

The development of Tavlia in late Roman dress, (the rectangular "patches" woven into the cloaks above) has been debated over the last year. It appears two things are clear: that they grew in size, and moved up the cloak from the bottom to the middle over the 4th-5th centuries.

Okay I left off in the middle of this because TDWP's livestream (which was amazing) came on. But I'm back!

Where did we leave off... oh yeah, Valentinian III's tunic.

Where did we leave off... oh yeah, Valentinian III's tunic.

So I've already described what his tunic *should* look like, the problem is that in this image, it's nothing like John Lydus describes. At least Aetius is wearing a Paragaudes even if it's wrong. Valentinian III is basically wearing a form of 10th century Divitesion.

His sleeves are long decorated cuffs which are meant to evoke the Persomanikia (buttoned cuffed sleeves) which sure, first appear in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiores, but Theophanes says that the first emperor to use them in a coronation was Anastasius.

Tight fitting cuffs and Persomanikia can be hard to distinguish, sure, but our best depiction of an emperor from Valentinian III's reign is that of Theodosius II in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, and he does not wear such cuffs.

I should briefly give some context since I've brought up this scene twice: this panel depicts Christ before David, but I wrote a paper arguing that it is Placidia and Valentinian III before Theodosius II, which for some reason nobody ever noticed before...

We also notice other features conspicuously lacking from Valentinian III's dress thanks to the San Vitale Mosaic: namely the presence of pearls hanging from the fibula pinning his cloak, and the lack of red shoes (Tzaggia or Tzangia or Tzancae, it's spelled like 5 different ways)

These Campagi are always red in art, which is probably a result of the fact a Tyrian purple simply cannot be achieved with authentic murex dye on the type of leather used. This would be a great area for experimentation, but damn would that cost a lot of money...

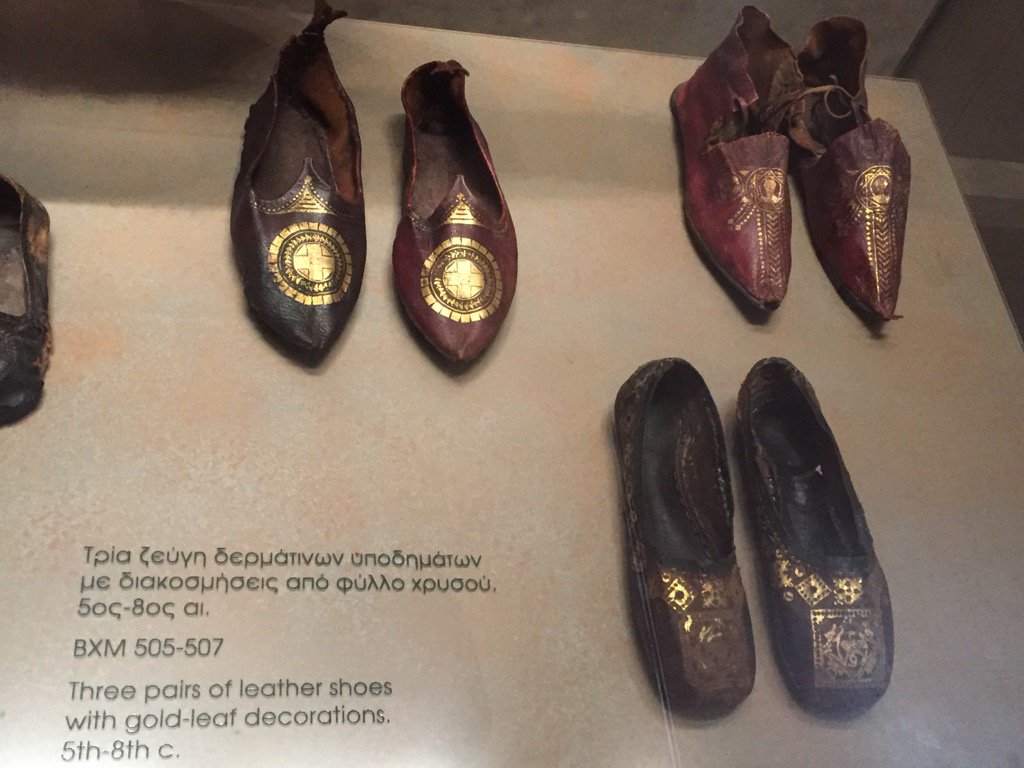

Several pairs of gilded, of red-dyed shoes from Antinoe have been recovered, all dating to the 6th-7th centuries AD. As far as I know, they are not murex-dyed, but even madder-dyed or cochineal-dyed shoes should theoretically result in you being executed.

The Class V shoe from the top right of that image is arguably 5th-6th century, but it's not really reflective of what we see in the art, which are open, low-riding Campagi like the Luxemborg examples. So whether it would be reflective of the Emperor's Campagi is hard to say.

And here we get into the issue of archaeology versus artistic interpretation. These aren't pairs of emperor's shoes, but they're very close, high status, and meant to imitate them. Are they representative? Or does the art supersede them in relevance to reconstruction?

Our best depictions also show an Emperor's shoes as more elaborately decorated than them, with pearls and stones. Again, Stilicho has done the best job reconstructing this, and here you can see an early Tavlion as well, positioned lower on the cloak.

Stilicho, by the way, is a man from Austria whom we all know by that name (he shares his real name selectively so I won't mention it). His impressions have gotten better and better, although a true representation is still out of reach for even someone like him.

Why is it out of reach? It's because there are only about 2 or 3 people in the world with the looms and skill to recreate these garments as they were actually made. That can cost anywhere from 4K to 30K depending on the complexity. Then throw in the cost of real Murex and Gold.

Reenactment/Living history suffers from this cost barrier, and we have to make do with what we can commission within "more reasonable" budgets (which can vary a lot for different people). A good reconstruction can cost as much as 10K or more...

But this research is important, because the living history community has repeatedly discovered things academics have not. The Ermine Street Guard figured out the correct arrangement of Segmentata Plates, & then Connolly got the credit... which is one reason why there is friction.

But when it comes to public history, living history and reenactment might be the most important form. Yes, there are a lot of really crappy people who do "reenactment," who put in little to no research and just want to hit people with swords.

But there are a lot of communities with that problem. Even academia is plagued by the same types of people who manage to get PhD's and then publish drivel. This is why we have peer review, after all. And it's why reenactors and academics need to work together.

Yeah we get mad when academics squander a 3 million dollar EU grant and deride us, but art like this is important to educating people. Roman emperors used art as a tool of power and propaganda and that kind of power of visual illustration still holds sway today.

Knowledge can leave an impression on viewers in a way that reading about something can't. I can describe a late Roman belt. I can show you a bunch of fittings. But having tried to describe to 3D modellers how it goes together, a reconstruction conveys things words cannot.

I do want to bring up a few last things before I finish off this thread. Emperor's belts are still under debate. Our best depiction is from the Missorium of Constantius II, which shows a belt with fittings similar to some early 4th century wide belts and the Kaiser-Augst ones.

However, we don't see these on the belt of Theodosius or Justinian, so it's hard to say what kind of belt Valentinian III would have worn. It certainly would have been gold and gem encrusted, more elaborate even than Aetius' belt in part one.

Another area of debated reconstruction is the "Stemma" or "Diadema" ("crown"). Sitlicho's, which you can see in the images above in his portrayal of Valentinian I, is decorated with small plates, with figures, and pearls with gems. But our evidence is purely artistic.

And... that's about it. At least for now. I'm not going to get into the architecture - the Ravenna palace's layout is not something I know much about, and only the borders and inscriptions from the Great Palace mosaics remain, so it's not something I feel I can comment on.

But I will close out by saying that Academia and Living History need to pay more attention to each other, instead of deriding each other. In the past 3 years major steps forward have been made in this, but recent months have taken major steps back too.

But ultimately both of our goals are to educate people and uncover new information about the past, and working together achieves this in a way each field individually cannot.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter