There's a massive statue of King Leopold II next to the Royal Palace in Brussels. When post-George Floyd protests against racism, police brutality and Belgium's horrific exploitation of Congo erupted this summer, demonstrators came for him. THREAD (1/n)

Belgium's leaders responded to the pressure. King Philippe for the first time expressed his "deepest regrets" for the "acts of violence and cruelty" committed by Belgium and linked that period to racism today. It was not quite an apology. (2/n)

But for an institution that still celebrated Belgium "bringing civilization" to Congo not long ago, it was a big step. Parliament also launched a truth, reconciliation and reparations commission to examine Its plunder of Congo under Leopold and the next 50yrs of colonialism (3/n)

The addition of "reparations" came after pressure from black Belgian activists, who wanted the country to not just admit fault and seek forgiveness, but to examine what exactly it owes to the country it exploited for 75 years. (4/n)

I was pandemic stranded in Belgium at the time, and it got me thinking about how we often talk about governments when we talk about reparations. But private enterprise is often the mechanism through which countries are exploited. What about them? (5/n)

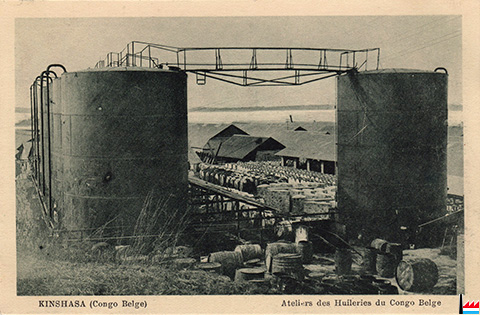

I knew Unilever descended from the Royal Niger Company, the British company that essentially owned Nigeria, and thought there might be some Belgian equivalent out there. It turned out there were a lot, including...Unilever, which partly began as Huileries du Congo Belge. (6/n)

I wanted to find a more direct connection to what was happening this summer, and that brought me back to that mounted statue of Leopold in Brussels. (7/n)

The statue, along with scores of others around the country, is an emblem of the willful national amnesia that Belgium underwent in the decades since Leopold was forced to hand Congo over to the Belgian state in 1908 after an international outcry. (8/n)

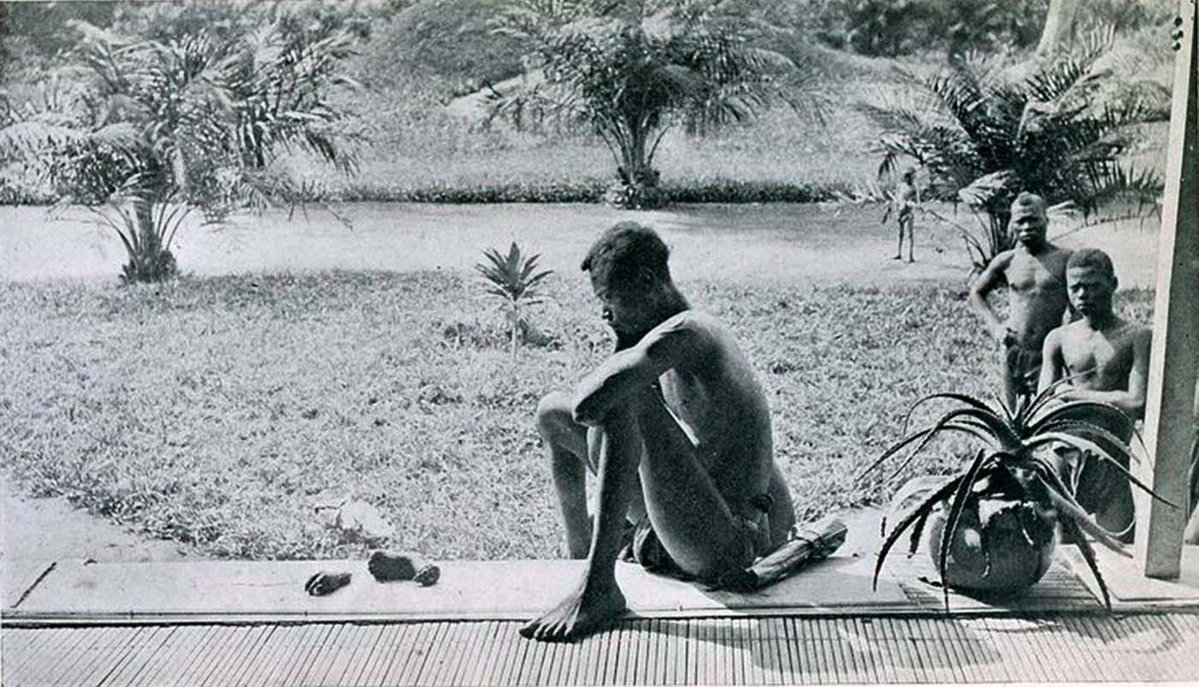

From 1885, Leopold's Belgians ripped rubber and ivory out of Congo, killing millions and notoriously cutting off the hands of their forced labourers if they did not meet harvest quotas. He was condemned by the likes of Mark Twain and, ironically, MPs in imperial Britain. (9/n)

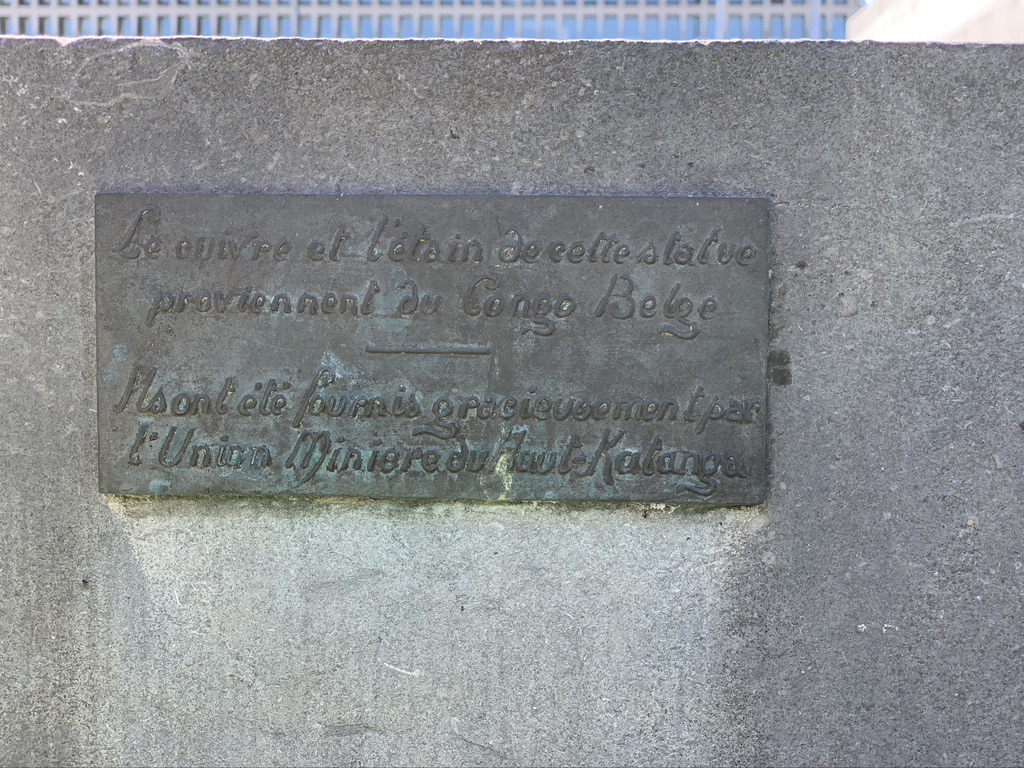

Cast in 1926, the statue is a monument to a brutal reign that brought Belgium great wealth. It is also literally a piece of Congo. I was in Brussels and walked over to see it. The city had just cleaned the graffiti off of it, ahead of a European Commission summit. (10/n)

It wasn't the cleaners' first rodeo. But they missed a spot: the palm of his curled right hand was still red. Then I saw a faded green plaque at the back of the base, which speaks of another kind of reckoning, which Belgium, and most of the west, is yet to have. (11/n)

“The copper and tin of this statue come from the Belgian Congo,” it reads in curved French script, stamped in warm, aged copper patina. “They were donated by the Union Minière du Haut-Katanga.” (12/n)

The plaque sent me into the history of one of the most significant companies in Congo's - and maybe Africa's - history: how it helped kill Congo's nascent democracy, its links to the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and the death of UN secretary general Dag Hammarskjold. (13/n)

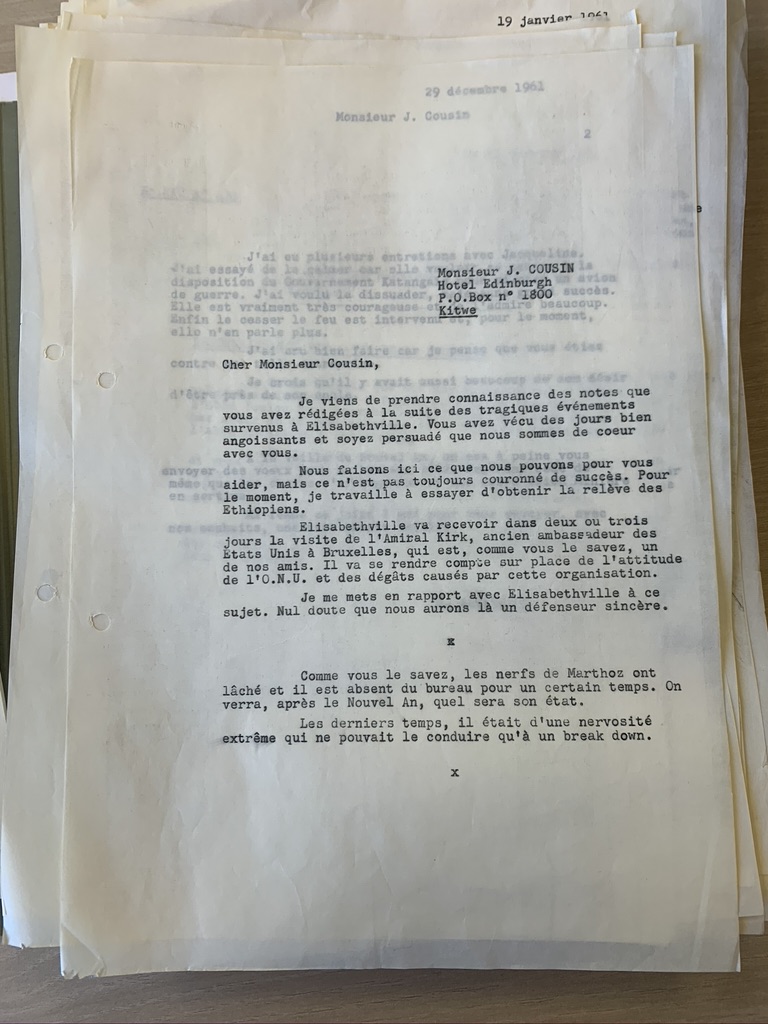

An old paper depot in Brussels houses UMHK's archives, which stacked up would be 57-stories tall. Leafing through onionskin sheafs of correspondence, a picture emerged of a vehemently anti-communist organisation seething with antipathy for Lumumba, and hostile to the UN. (14/n)

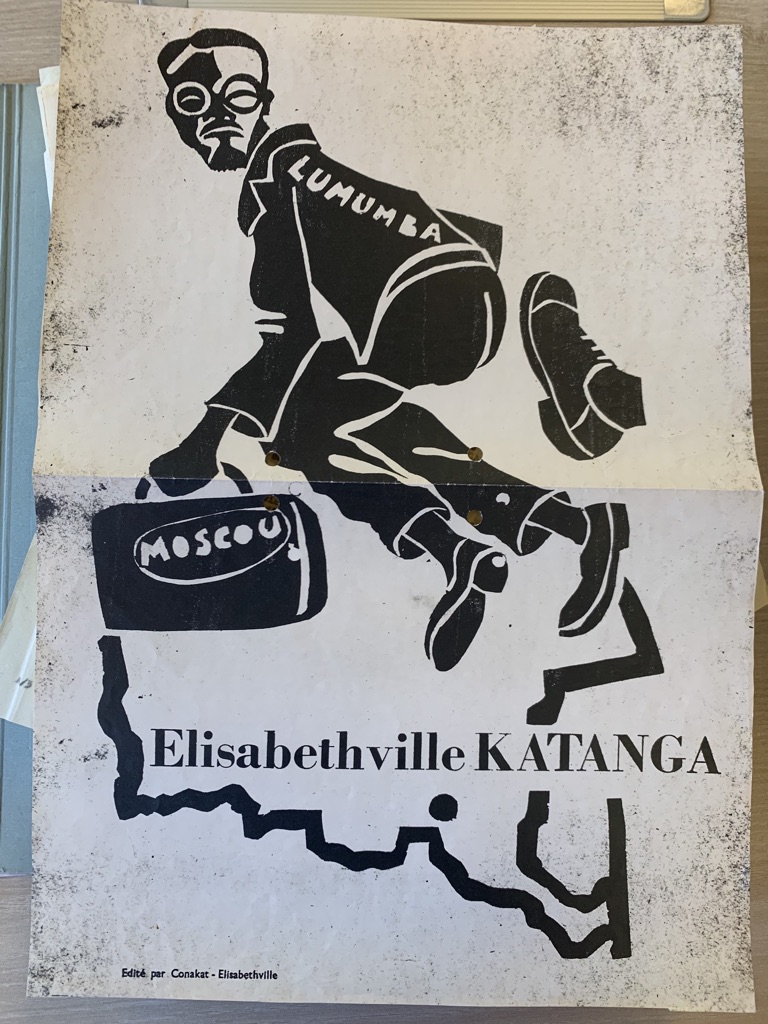

Here's an anti-Lumumba poster that basically jumped out of one of the file boxes, from one of the parties funded by UMHK, which also paid for hundreds of white mercenaries to fight for the secession of copper rich Katanga soon after independence. (15/n)

There was so much more. The corporate descendants of UMHK still exist today, some as legally new/different companies. But it is far from alone. (16/n)

Heineken’s horrific history in Africa was exposed in a 2018 book by journalist Oliver van Beeman that was debated in Dutch parliament. Lufthansa’s Brussels Airlines started as Sabena, the state-owned carrier servicing Belgian interests in central Africa. (17/n)

UMHK was but the biggest part of the conglomerate Societe Generale du Belgique, which at one point controlled 70 per cent of Congo’s economy. Pieces of SGB have found their way into Suez, BNP Paribas Fortis and the French energy giant Engie. (18/n)

The mounted statue of Leopold is facing the glass-and-steel offices of ING Belgium, which was originally the king’s personal banker, Banque Lambert. The debts these companies owe - or do not owe - are hard to quantify. (19/n)

I grappled with these issues in a piece for @FTMag. I hope you'll read it. (And if I have time I'll share some other wild stuff I learned while reporting, including about major UMHK shareholder controlled by a powerful group of Tory parliamentarians.) https://www.ft.com/content/a17b87ec-207d-4aa7-a839-8e17153bcf51

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter