1. This is a thread about rightful BRITISH PELICANS. The Dalmatian Pelican – a native Briton. The largest flying animal. The largest freshwater bird on Earth. Dwarfing eagles, this awe-inspiring bird soars on three-metre wings. Here we’ll explore how these giants could return.

2. Once upon a time, into the Roman Occupation (43AD) and beyond, the Dalmatian pelican was our largest British bird. Breeding, at least, in the marshland deltas of Somerset & East Anglia, the peat-land fossil record attests firmly to its presence.

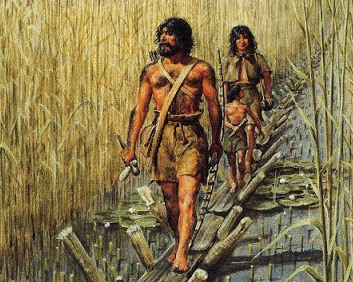

3. We know, from the fossil record, and cut-marks on UK pelican bones, that our ancestors were not averse to snacking on these vast & meat-rich birds & presumably their chicks. Were I in their place - hunting those marshes by boat & wooden walkways - I might have done the same.

4. Although, as said, the last fossil of Dalmatian pelicans dates to 43AD, one chanced fossil does not, of course, represent the last bird. Fossils are merely a hint of what we once had. That said, Medieval folklore does not recount pelicans so we do know they vanished early on.

5. Given the monks only began draining the Great Fens centuries later, human activity, rather than habitat loss, is the most likely factor to have driven pelicans from our shores. Historically, the largest, edible and most easily-predated species have generally vanished first.

6. Gone for the best part of two millennia, why is it so important that we restore our pelicans? Why resurrect something long gone from our island home? Why seek out giants, when many seem happy with bitterns or marsh harriers? This is why.

7. Imagine if, each year, over centuries, our art galleries were plundered, the human death rate greatly increased and our societies fell into ruin and emptiness. We wouldn’t accept that for ourselves. In my view, we shouldn’t for our ecosystems & fellow species, either.

8. Since the Bronze Age, and long before, every generation has been, progressively, robbed of wild life. Now, we can only see how depauperate Britain has become, by visiting areas of the world where such acts of robbery have yet to take place (pelican's former range, below).

9. Long bereft of thriving ecosystems, charismatic cornerstone species & teeming bio-abundance, we have sometimes become tied to protecting the tiny relics of ecosystems - rather than asking what is the maximum amount of life we could return to the land.

10. Now, however, things are beginning to change. Rather than simply protecting what David Quammen calls ecosystem ‘scraps’, we are beginning to see many of our marshland fragments restored and joined up: back into rich ecosystem tapestries of ever-greater scale.

11. And yet, even with many of our marshlands now being restored, created & joined up, Dalmatian pelicans will not magically re-appear. They have no natal memory of Britain – and so, having taken them out, we – as the species in charge in the Anthropocene – must put them back.

12. The first question, then, is do we have enough suitable habitat? Not yet in my local Somerset, but there are similarities between the East Anglian coastline (Broadland & N Norfolk) & the Volga, where pelicans nest in reed-beds but feed too in coastal waters & lagoons.

13. The aggregate acreage of fish-rich waters - in the Broads, Fens, Norfolk Coast and the Wash - is, in fact, greater, than habitats used by small but growing populations in countries like Montenegro. We lack areas as large as the Danube, but we have space enough for pelicans.

14. With a small but stable population of giant pelicans possible in our country, what could this look like? How does this bird behave, fly, nest, move and, perhaps most importantly, fish? How might pelicans dovetail into our existing reserves? In my view, really rather well.

15. After a successful reintroduction, young pelicans would take a few years to orientate themselves, before committing to nest. When they do, pelicans are fussy. They nest, loosely aggregated, in undisturbed reed-beds. But man-made islands help. A secluded site would be key.

16. Based on current calculations, there are perhaps 3-4 sites in East Anglia suitable for hosting nesting – but feeding would happen throughout. Dalmatians don’t ‘gang-fish’ like other pelicans – in fact, they tend to spread out. Each will eat around 1.2kg of fish per day.

17. Imagine, then, that, like I did as a child, you’re sitting patiently in a hide at Cley Marshes. You may not see 100 pelicans descend at once. But even a couple, soaring on 3 metre wings, may be the finest thing you’ve ever seen. They'd then soar off, back to the colony.

18. Over time, pelicans will integrate back into our avian community. Those who hate change & ambition will grumble. A few anglers who haven’t cottoned on to pelicans being lucrative for fishermen (as in Greece) will grumble too. The vast majority of the public will be entranced.

19. Soaring effortlessly between the ever-growing marshes of East Anglia, dalmatian pelicans will become the crowning glory of conservation wetlands famous across the world. Their presence is likely to help enhance the protection of fish stocks; a flagship indicator species.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter