Seeing how I can't do any damned work today and it is Captain Dan's Storytime....

Who wants a Veterans Day thread about a guy I knew?

Who wants a Veterans Day thread about a guy I knew?

OK. Take a seat. This is going to be a wild ride. It is now Captain Dan's story time, Veterans Day edition.

I am a member of the American Legion and want to tell you about the guy who led my Legion post for many years.

Although the American Legion is a bog-standard veteran’s organisation, it is usually planted in the American consciousness as a slightly down-at-the-heel 1950s/1960s vintage building serving cut price booze and low-grade food to veterans.

The idea of a post in exile strikes some as fanciful. And, indeed, I have met numerous fellow legionnaires who flat out refused to believe China Post existed until they saw my card. It’s guaranteed to get some odd stares in rural America.

You can read about the odd history of China Post 1 here. https://chinapost1.org/history/

The China Post got some notoriety, a little of it well earned, some of it specious, in the 1960s through the 1980s as some sort of secretive clearing house for dodgy dealings and mercenaries.

It is the place in the American Legion where the oddballs, the spies, the secret warriors all collect. It has been mentioned numerous times in fiction, the popular war fiction writer Web Griffin being the most infamous culprit. But he’s allowed as he is himself a member

Now I come Captain Fred Platt, who served for 25 years as the leader of China Post. He was, by far the bravest man I ever met, and I know many honest-to-god war heroes who also say that about him. Fred died in 2016.

He was born Alfred Gerald Platt, on February 4th, 1941 in Houston. He went to the University of Texas and graduated in 1963 with a degree in Business.

He joined the US Air Force to become a pilot. His early career saw him languish in Air Traffic Control, not as a pilot. Eventually he became a B-52 co-pilot.

Although he was really eager to get in on the growing war in Vietnam, he was assigned to the newest version of the B-52, which was part of the strategic nuclear deterrent, not part of the Vietnam war.

By all accounts, Fred was a reasonable B-52 pilot. But it wasn’t where the action was. He learned of a program to train forward air controllers.

These are the guys who fly around in small light aircraft directing in the other heavier combat aircraft to make their airstrikes and such.

Vietnam was taking as many of these as possible. Fred graduated quickly from Forward Air Controller training and found himself in Vietnam

Vietnam was taking as many of these as possible. Fred graduated quickly from Forward Air Controller training and found himself in Vietnam

While serving creditably, young Capt Platt finds himself quite frustrated with the extensive rules of engagement and bureaucracy that plagued the conflict. Fred spends more of his time at the airfield than in the air.

But Fred hears rumours of a more active war in the neighboring country of Laos. Where the war is hot, pilots are swashbuckling adventurers, and the bureaucracy is distant.

We don’t hear much of his service in Vietnam, but he was good enough to be asked to volunteer to join in the secret war next door.

The “secret war” in Laos was an odd thing. It was as if a whole other war was running in parallel to the “official” open war in Vietnam. The war in Laos had numerous dimensions to it.

In the context of the war in neighboring Vietnam, Laos contained much of the supply route, the so-called Ho Chi Minh trail, which allowed North Vietnam, as well as China and the Soviet Union to supply the communist forces fighting in South Vietnam.

Laos also had its own struggle with communist insurgents, the Pathet Lao, and long-running animosities between political factions and ethnic groups that played out on many levels.

In this complex Laos war, the US was fighting covertly, with a large army of hill tribesmen, the Hmong, under command of their general Vang Pao (who lived in Montana in exile and died only a few years ago).

The US Central Intelligence Agency armed and supplied Vang Pao’s army, taking over a role that the French had played when Laos had been a French colony.

As an international agreement had prohibited open US military presence in Laos, it was done on a covert basis, by paramilitary specialists from the CIA on the ground advising and arming the Hmong.

Laos is a hilly country and the road network is inferior, so the CIA’s war there developed a heavy reliance on air mobility and airpower as a substitute for ground mobility and artillery.

The US military trained Thai, Lao, and Hmong pilots to fly old T-28 propeller aircraft as combat air support. But local air power was insufficient. Huge amounts of US Air Force and US Navy airpower were directed onto the Laotian war.

Enter Fred Platt. The air force needed ways to direct their air power. Local troops usually couldn’t speak English well enough and lacked the requisite training to call in air strikes.

So, the air force supports the cover war with something variously called Project 404 or Project Steve Canyon, after the comic book character.

They put some seasoned volunteer forward air controllers, to be known in Laos by their call signs as Ravens, into Laos, in plain clothes, flying light civilian aircraft, such as Cessnas.

Incidentally, the Ravens veteran group is called the Edgar Allen Poe Literary Society, in a nod to the poem, The Raven.

Usually with a local Hmong or Lao counterpart as a “Backseater”, these guys became the air reconnaissance, air traffic controllers, and effectively traffic cops of the secret air war.

Flying at times just above the tree tops at great peril, making many sorties a day, they quickly become absolutely essential to the war effort.

They live and work along side the CIA’s secret army, in small bases and small airstrips, usually for six months at a stretch, but many (including Fred) extend their tours.

The Ravens get a reputation as crazy rogues, cowboys, and adventurers. In Fred’s own words: “It really had the feel of some pirate hideaway, with guys with tattoos and daggers clutched between their teeth.”

Fred arrives in Laos through a process known as sheep-dipping. He goes to a US air base, turns in his uniforms and military IDs.

Ravens were often given cover documents as “forest rangers” “agricultural advisers” and somesuch.

They fly over to Laos, usually on an Air America plane, and are briefed by the Air Attache’s office in Vientiane, the Laotian capital. Fred is assigned the callsigns of Raven 47 and “Cowboy”.

Fred now enters into his own. He becomes a hero’s hero. The bravest of the brave. A wild man among wild men, Fred was banned from town for various infractions and had to stay out in his rural base.

Flying low and slow, for hours, he had an uncanny ability to knacker an airplane and somehow make it back. Flying close to the treetops to find the enemy, Fred returns his airplanes back to base with more holes in them than previously thought possible.

His callsign is changed to “MagnetAss” – a callsign which has never been given to anyone else. Fred used up 10 aircraft in combat. And an 11th one is sometimes cited.

Fellow post member @webgriffintales will forgive me for posting this little bit from his novel "The Shooters"

There’s some controversy on this, the 11th shoot-down was, by Fred’s account a mechanical failure during a training flight, albeit a harrowing crash he was lucky to walk away from.

There are numerous anecdotes about Fred’s heroic exploits. Some are folklore. and I don’t have time to tell them all.

I focus now on the ones that have been thoroughly researched and can be attributed to multiple sources. A few years ago, I communicated with Fred’s fellow Ravens.

Fred’s first crash was an outing with Major Joe Bush, an Army attaché from the US embassy. The weather was so bad that the US Air force and their local allies were unable to fly. So Fred and this army major engaged in unofficial bombing.

They used 155mm artillery shells wrapped in detonator cord as improvised bombs and dropped them out the doors of their Cessna. Due to bad weather, they had to crash land. (Nod to @hdevreij my Artillery guy.)

Fortunately, they were in friendly territory and were easily rescued. But Fred needed a new plane as a major operation was about to start the next day.

A Thai army unit had a mothballed Cessna Bird Dog plane, and Fred bought it from them for $100 cash, got an air force mechanic to work it over, and got back into the fight.

And he got into a major operation the next day, cheating death as his hut was struck by a rocket.

In another instance, Fred flew nine sorties in one day. He was flying with a young Hmong backseater, and on their last mission, they were hit by antiaircraft fire. The young Hmong guy was seriously wounded and was unlikely to make it back.

Fred flew the plane largely with his feet while he amputated the mangled leg with his bowie knife, and used a belt for a tourniquet. He got the man back alive, and he lived to tell the tale.

In perhaps the most famous incident, a Hmong forward base was under heavy attack by the North Vietnamese army. The weather was too officially poor for air support, but not for The Ravens, who know the terrain and could fly it blindfolded.

One of the Ravens (some say Fred, some say they don’t know who) come up with a crazy plan to use three of their Cessnas as light bombers.

They piled everything that could possibly hurt the enemy into their planes – machine guns, hand grenades, grenade launchers, smoke rockets normally used for marking targets, improvised bombs, mortar shells wrapped in det cord, etc.

They kept buzzing the enemy positions. Fred was flying and literally leaning out the window with aM79 grenade launcher Others shot machine guns. In weather where the cloud ceiling was literally feet over the tops of the trees.

They forced the North Vietnamese to retreat. The stuffy gits in the US Air Force were apoplectic. In the US military, the only thing as bad as losing a battle is winning an unauthorised one.

The one thing that kept Fred from getting court-martialled was the fact that General Vang Pao nominated him for the Air Force Cross, the second highest award a pilot can get, just shy of the Medal of Honor, and held a baci – a warrior’s banquet, in his honor.

Fred Platt also had a predilection for collecting exotic animals. In fact, the first time I ever heard about Fred his name wasn’t even mentioned.

I had occasion to know a retired CIA guy who had been a paramilitary advisor in Laos.

He said something like – “Man, there were these crazy pilots, way crazier than anyone. One of them even found this creature, it was some kind of armadillo or armor-plated anteater, and flew with it on missions.”

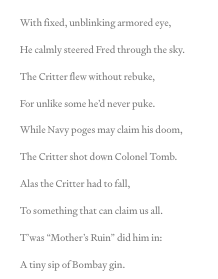

I only worked out years later that this was Fred. Indeed, Fred had this thing, called the Critter, that he found after one of his many crash landings.

It was a creature called a pangolin, basically a scaly anteater. It became the Raven mascot for a while until it sadly died from drinking a martini

On at least one other occasion, Fred turned up at the air strip with a bear cub, named Ho Chi and took it on a mission instead of the Laotian back-seater who refused to fly with Fred.

Attempts to tame a tiger cub were unsuccessful. Indeed, the tiger escaped.

On January 11, 1970, Fred flew what turned out to be his last mission and wrecked his last aircraft. He was breaking in yet another new backseater and was looking for targets to mark for US air strikes

After using one of his marking rockets to attack a cache of fuel barrels he found, his plane was stitched up bad by antiaircraft fire.

With his cockpit full of smoke, and flying literally 3 feet above the ground, he managed a rough “Alaskan bush pilot” crash landing in a field.

It was a hard landing and the propeller hit the ground, causing the plane to flip over. As he fell out of his plane and pulled his stunned backseater out, enemy troops appeared, 500 meters away.

Grabbing his weapons, and throwing the stunned and injured backseater over his shoulder, he ran for cover.

Using his grenade launcher (incidentally making him one of the few Air Force personnel to enter ground combat with a grenade launcher) and an unauthorised Swedish submachine gun, he fended off the attackers.

He fended them off long enough for an Air America helicopter pilot named David Ackerberg to find them. They were rescued.

Fred’s war was over. The next morning he couldn’t move his legs. He was evacuated back to the states. On his way out of SouthEast asia, he punched a colonel and nearly got courtmartialed for it.

The long, hard recovery he made is well documented in Christopher Robbins book “The Ravens”.

Although Fred gradually hoodwinked some air force doctors into letting him fly again, but when a high-ranking officer from the Air Force surgeon-general’s office saw him literally being carried into the cockpit of a T-33 jet, he was rumbled.

As often as is the case, information sometimes trickles out after death. I’m not sure what the world records are in this department, but Fred’s official statistics are impressive.

He officially logged 1716 combat flying hours on 745 combat missions in single engine propeller aircraft at a point when most of the combat pilots in the air force were flying jets.

By means of comparison, many brave and good men were sent home from WW2 or Korea having flown 50 or 100 missions.

Fred wasn’t one for wearing his medals, and now I know why. They wouldn’t fit.

the Silver Star, three Distinguished Flying Crosses, 26 Air Medals, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Gold Palm, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Bronze Star, 3 Purple Hearts, and a host of lesser decorations too numerous to mention

Due to his, erm, colourful relationship with his superiors, the list of medals he was recommended for, but denied is likely to be long. If there's a posthumous campaign for that Air Force Cross medal, I'll be behind it 500%

Fred could have easily gone into quiet retirement. He spent the rest of his life in a great deal of pain.

He got a lot of pro bono help from the doctors and physios at the Houston Oilers football team, and a lot of the therapy he got was experimental at the time, but now mainstream.

But for a guy who was partially disabled, in a lot of chronic pain, and pensioned off from the US Air Force at the age of only 31, Fred got up to a lot.

Fred got involved in many different organisations, both military and otherwise.

Things like the Air Commando Association, The Edgar Allen Poe Literary Society (at least one Raven had a sense of humor), the Special Operations Association, the Air Force Escape and Evasion Society, and the Houston Stock Show and Rodeo.

He and his fellow ravens did a lot for Hmong refugees in America. Vang Pao awarded him the honorary rank of General. And he became a member, then the leader of China Post, a position he held for 25 years.

He was, in effect, the best shop steward that veterans of the secret wars could ever have. And one hell of a guy to drink a bit of Mao Tai with in the parking lot at Arlington Cemetery.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter