New paper: "Automation and the Fate of Young Workers: Evidence from the Automation of Telephone Operation in the Early 20th Century" joint with @jamesfeigenbaum, available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w28061 . TLDR: skip to end (1/25)

New paper: "Automation and the Fate of Young Workers: Evidence from the Automation of Telephone Operation in the Early 20th Century" joint with @jamesfeigenbaum, available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w28061 . TLDR: skip to end (1/25)

Automation is a hot topic these days, with concerns that it may have already displaced millions of workers and threatens millions more. COVID has only intensified these concerns, since machines can't spread a human virus (though they have their own viruses). (2/25)

A lot of scholarship from the SBTC canon explores the pace of automation, its effects on labor markets, and how the economy adjusts. Much of this literature has focused on industrial robots in manufacturing, today. You can see many examples of important work below. (3/25)

We take a different approach. Many of the routine, entry-level jobs that are at high risk of automation, like cashiers or customer service reps, provide a pathway into the workforce for millions of people---especially young people. (4/25)

Automation not only puts existing workers at risk: it's even more threatening to future generations, who (collectively) vastly outnumber the current crop, and who lack protections like UI, unions, or job transfers if they can't find work in the first place. (5/25)

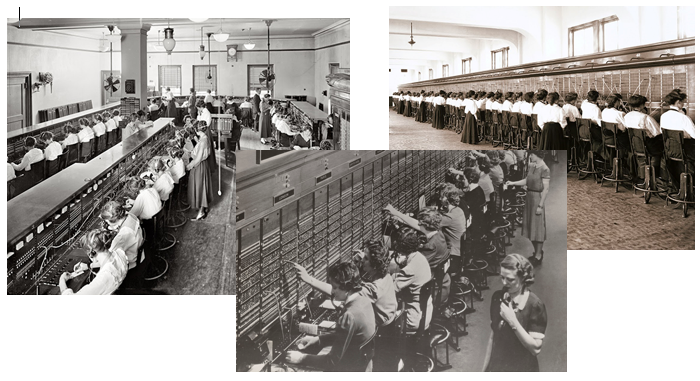

From this launchpad, we study one of the largest youth-specific automation shocks in U.S. history: the automation of telephone operation in the 20th century. In the 1920s, this was one of the most common entry-level jobs for young women, esp. young, white, US-born women... (6/25)

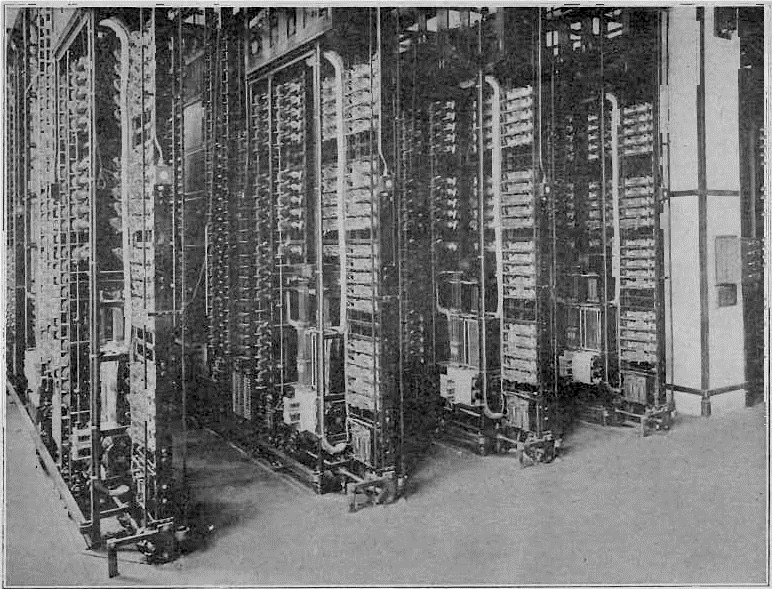

... and employed hundreds of thousands, nearly all at AT&T operating companies (AT&T was itself the largest US employer). Over the next 50 years, AT&T replaced operators with mechanical switching and dial service. By 1940, over 60% of the AT&T network was already dial. (7/25)

We use census data on the entire U.S. population from 1910 to 1940, a longitudinally-linked sample of women, and a new dataset measuring local adoption of mechanical switching to find out what happened to incumbent operators and future generations of young women. (8/25)

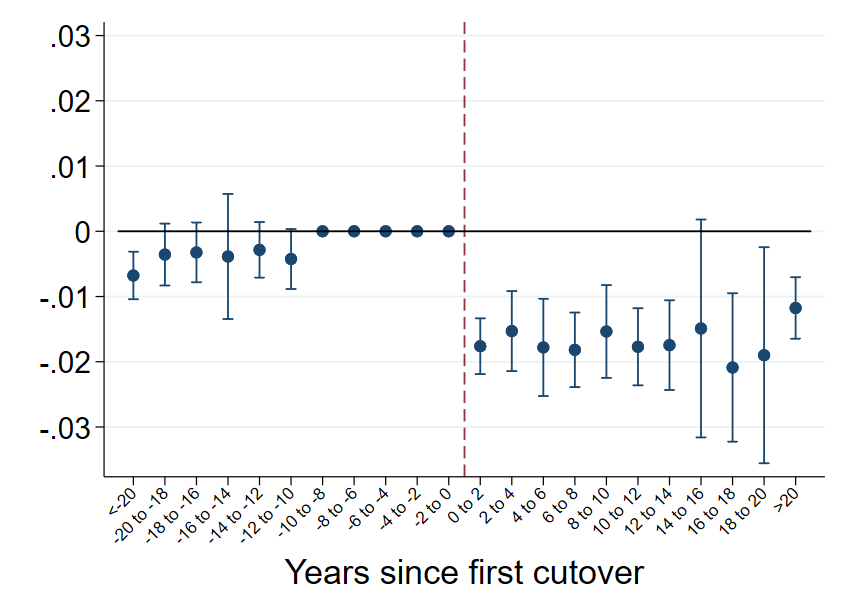

The technology had bite: after a city went dial, the number of young women in subsequent cohorts who were telephone operators immediately, permanently dropped by 50-80%. This abruptly eliminated around 2% of employment for this population. (9/25)

But it affected many more: this was a relatively high turnover occupation, a stepping stone, that we estimate might have provided work to as much as 10-15% of these women at some point as a young adult. Our question is: what happened next? (10/25)

Despite its magnitude, this shock did **not** reduce future cohorts' employment rates. It appears that some other jobs grew to take its place. One of these was typists and secretaries, which required similar skill levels and paid similar wages. Example below. (11/25)

Another was lower-skill, lower-wage service jobs in restaurants or beauty parlors. Working women of the youngest ages (16 to 18) tended to be in these lower-paying jobs, while "older" young women were in similar-paying jobs. On the whole, both groups seemed to fare okay. (12/25)

But this only describes how *future generations* adapted to a labor market where telephone operation was automated. What about the women who were operators just before mechanical switching was adopted? (13/25)

Studying women over time in historical data (esp. young women!) is notoriously hard to do, because their records have to be linked across censuses, and their surnames typically changed at marriage. But @jamesfeigenbaum has found an elegant solution. (14/25)

We use genealogy platform FamilySearch to link telephone operators and their demographically-similar neighbors in 1920 and 1930 to their own records across censuses, relying on matches made by descendants and genealogists. (15/25)

With these data, we can estimate differences in the 10-year outcomes of women who were telephone operators in cities that were vs. weren't automated, relative to those of same-age, precisely demographically-similar working young women from the same neighborhood. (16/25)

We find that incumbent operators where telephone operation was automated were subsequently less likely to be working in the next decade where we observe them, and conditional on working were more likely to have switched to lower-paying occupations. (17/25)

The size of these effects is tempered by the fact that at this time, many women exited the workforce as they aged. But this was one of the few jobs for women with the potential to be a career, and the loss could be costly for those who would have chosen to keep them. (18/25)

Collectively, our results suggest local economies can adjust to automation shocks over relatively short horizons and continue to absorb the steady stream of young workers entering the labor market. The incumbent workers who get replaced may be most at risk. (19/25)

The question we're left with is why other jobs grew to fill the gap created by automation. Was this inevitable? The technology itself didn't create much demand in these other jobs for women (though it did for a few predominantly-male jobs, like engineers at AT&T). (20/25)

Instead, our reading of the evidence is that under the right conditions, labor demand was growing in jobs that benefited from the skills of would-be operators, like secretarial work, consistent with the intuition of @DrDaronAcemoglu and @pascualrpo (AER 2018). (21/25)

What shores up this interpretation is seeing exceptions to the rule: in cities hit harder by the Great Depression, where labor demand was more slack, automating telephone operation had more negative employment effects. (22/25)

It's also important to recognize the historical context: this was a time when women's educational attainment and labor force participation were growing broadly, and demand for women in white-collar occupations too. We don't think we can attribute these broader trends ... (23/25)

... to the automation of telephone operation, nor do we find that automation itself was a reaction to these trends. But they were in the background, nationwide, and could potentially be important to the story. More research needed. (24/25)

TLDR: (i) young workers are an important but vulnerable subgroup when it comes to automation, (ii) local economies can adjust to accommodate future generations of workers entering the labor market, and (iii) incumbent workers are nevertheless at risk. (25/25)

Postscript #1: An ungated version of the paper is available here: https://www.dropbox.com/s/tjdeuoa3letu90v/AFYW_20201031.pdf?dl=0

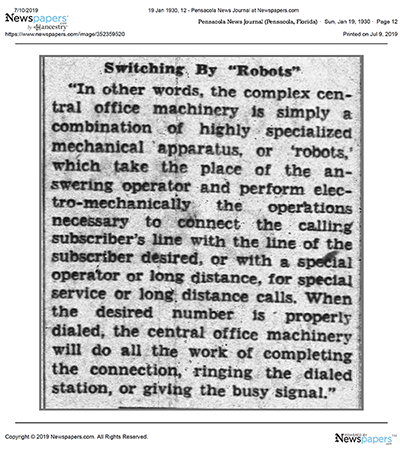

Postscript #2: If you think robots are just for industry, think again. Here's a newspaper article from 1930 on "robots" replacing telephone operators.

Postscript #3: Our favorite telephone operator

Postscript #4: Automation anxiety ca. 1980:

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter