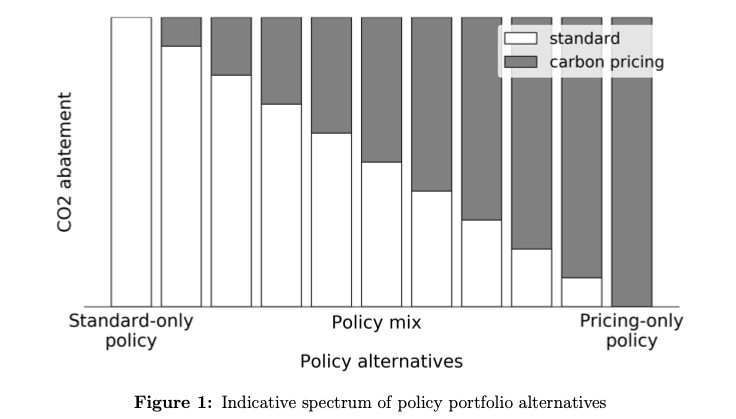

Climate policy debates have pitted CO2 pricing vs standards but there is a whole spectrum in-between.

Our new research w/ @KnittelMIT finds that given political realities a combined policy may be a promising way forward.

http://ceepr.mit.edu/publications/working-papers/747 (DM to request copy if non-comm)

Our new research w/ @KnittelMIT finds that given political realities a combined policy may be a promising way forward.

http://ceepr.mit.edu/publications/working-papers/747 (DM to request copy if non-comm)

For context, there are many reasons climate policy requires a portfolio of approaches. Many economists would say it requires correcting not one but multiple market failures. Pricing and standards can be seen as complementary. (e.g. see great work by @BorensteinS, @RobertStavins).

Dynamic and strategic perspectives (found in various schools incl. evolutionary economics) argue that technology policy is called for to break our current path dependence and chart new courses (e.g. insightful research by @MichaelGrubb9 @camjhep @anthonypatt @dan_rosenbloom.)

Critically, there’s also politics. Efforts to implement carbon pricing have repeatedly proved challenging. Various jurisdictions rely on policy portfolios containing standards and other policies, sometimes including low carbon prices (as in EU, California, New England, Canada).

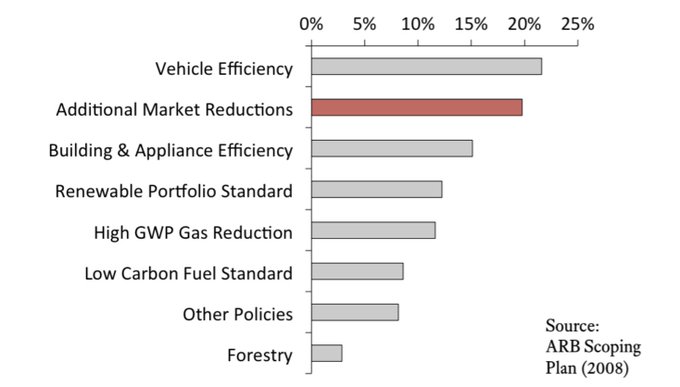

In the EU, Cal., New England, Quebec, I'd argue pricing in the form of cap-and-trade has played the role of a backstop: ensuring emissions are met via the cap but being relegated a small role in overall emission reductions (e.g. see figure of original Cal. plan by @dcullenward).

Given political limits on pricing, other policies such as standards become necessary (even w/o the multiple externalities and dynamic perspectives), as I and many have argued (e.g. important work by @MarkJaccard @BarryRabe @leahstokes @JesseJenkins @GernotWagner).

Standards occupy a central role in the national discussions in the US, e.g.:

- the 2020 House Committee report (details in my thread https://twitter.com/EmilDimanchev/status/1277978305694556161?s=20)

- Biden’s plans (my threads here: https://twitter.com/EmilDimanchev/status/1313841593103904771?s=20)

- Prominent platforms: https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/21252892/climate-change-democrats-joe-biden-renewable-energy-unions-environmental-justice

- the 2020 House Committee report (details in my thread https://twitter.com/EmilDimanchev/status/1277978305694556161?s=20)

- Biden’s plans (my threads here: https://twitter.com/EmilDimanchev/status/1313841593103904771?s=20)

- Prominent platforms: https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/21252892/climate-change-democrats-joe-biden-renewable-energy-unions-environmental-justice

Meanwhile, CO2 pricing has been featured in multiple bills. See @noahqk on this (e.g. here https://twitter.com/noahqk/status/1291803831068766208?s=20).

And where CO2 prices already exist, their role is continuously being debated and revised (e.g. #EUETS, Cal., Canada, cc. @EcofiscalCanada)

And where CO2 prices already exist, their role is continuously being debated and revised (e.g. #EUETS, Cal., Canada, cc. @EcofiscalCanada)

To inform these discussions, @KnittelMIT and I study the cost-effectiveness (aka efficiency) of different climate policies differentiated by how much they rely on standards or carbon pricing to achieve a given level of CO2 reduction.

Most previous research compares standards and carbon pricing in isolation: comparing a standard-only climate policy to a pricing-only policy. Here, we look at policy making as a choice between *alternative combinations* of these two policies. Where on the spectrum should we be?

The purpose is to help policy making navigate the trade-offs between the political acceptability of standards on the one hand and the cost-effectiveness of carbon pricing on the other. Or as @ElephantEating formulates the general question: https://twitter.com/ElephantEating/status/1266069038704275456?s=20

How do we do this? @KnittelMIT walks through the analysis here: https://twitter.com/KnittelMIT/status/1325856447490560000?s=20

I will summarize (though there may be a little repetition), expand on some underlying dynamics, and go through some of the implications.

I will summarize (though there may be a little repetition), expand on some underlying dynamics, and go through some of the implications.

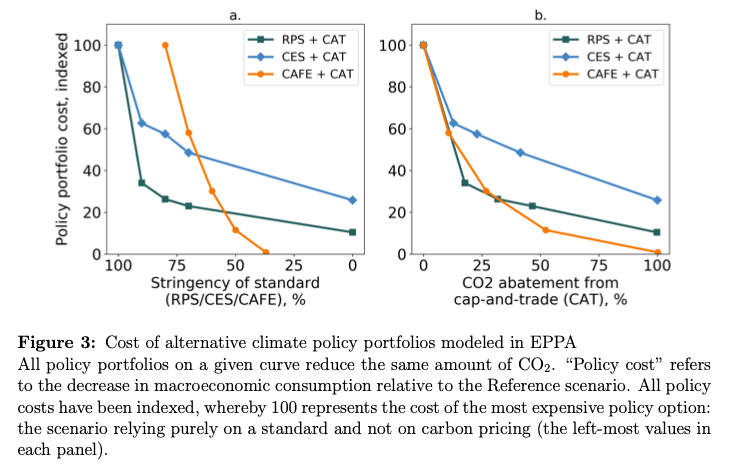

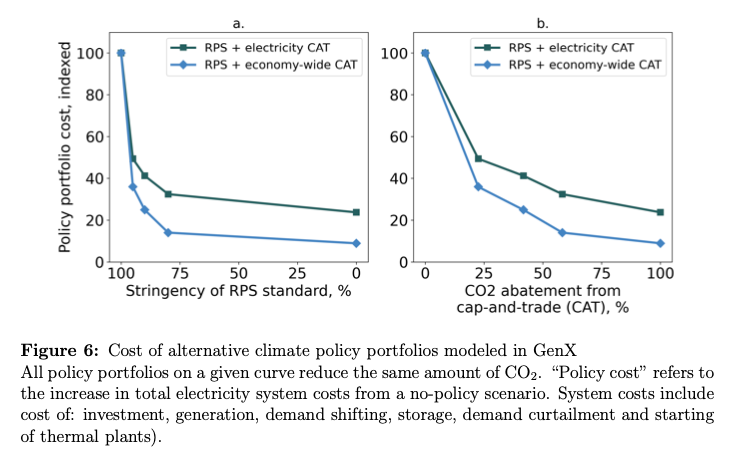

In short, we use both theory & modeling to test the following: for a given level of CO2 reduction, how does policy cost (y-axis) vary along the spectrum (shown in two different ways on the x-axes) b/n standard and pricing. Results from two models (EPPA & GenX) illustrate.

Different points along each curve refer to different combinations of a standard and CO2 pricing (modeled as cap-and-trade) that reduce the same amount of CO2 but differ with respect to how much they rely on standards or CO2 pricing to drive the CO2 reductions.

There are two main takeaways. The first is that a combination of pricing and a standard costs less than a standard-only policy that reduces the same amount of CO2 (cost declines as we go from left to right in the figures). This is as expected based on previous research.

More importantly, the cost-saving benefit of pricing shows diminishing marginal returns.

This suggests that carbon pricing follows the Pareto principle: some pricing delivers a disproportionately large share of the benefits of optimal pricing-only policy (at a given CO2 level).

This suggests that carbon pricing follows the Pareto principle: some pricing delivers a disproportionately large share of the benefits of optimal pricing-only policy (at a given CO2 level).

The paper’s main contribution is thus to suggest that, by adopting modest carbon pricing, policy makers would accomplish a disproportionately large share of the cost savings of economically optimal carbon pricing.

E.g. a policy portfolio including a 90% RPS and a cap-and-trade costs 66% less than a 100% RPS w/o pricing (dark blue square in EPPA results, panel a). In this case, the CO2 price delivers large savings while playing a modest role, causing only 18% of CO2 reductions (panel b).

What drives the findings? We identify 3 ways in which combining a standard with a carbon price results in cost savings relative to relying on a standard alone to deliver the same amount of CO2 reductions.

First, our theoretical model suggests that when a low-carbon standard and carbon pricing are applied to the same sector and same set of products, the pricing incentivizes a more efficient production mix (e.g. prevents overproduction/overconsumption).

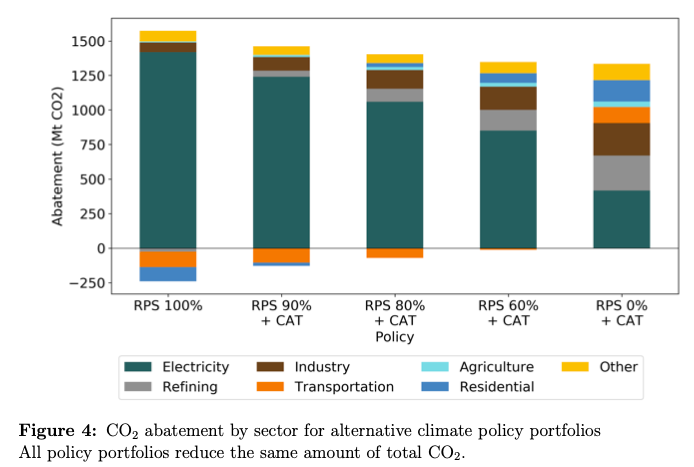

Second, carbon pricing that covers additional sectors incentivizes cheap CO2 abatement options outside of the sector being covered by the standard. Our EPPA results show that cheap abatement options exist in a variety of sectors outside electricity.

Third, a carbon price applied to the same sector as the standard can also incentivize technological options outside of the scope of the standard (e.g. a new technology not being covered by ex-ante eligibility criteria of the RPS/CES).

It bears noting: while this analysis is premised on political constraints, the focus is on cost-effectiveness. We do not quantify the political trade-offs between different policy combinations. An unresolved Q is how “politically expensive” different CO2 prices actually are.

There are additional considerations such as climate justice, which we could not address but which must also inform the choice of a policy portfolio. Revenue raised through modest carbon pricing may provide a way to balance any policy regressivity.

In closing, modest CO2 pricing has large marginal benefits. This suggests that a policy portfolio that combines a standard with modest CO2 pricing could enable a balance between the political advantages of standards and the cost-effectiveness of pricing.

We would love to hear your feedback. I am tagging folks I’ve either discussed this with or who I think may be interested. @noahqk, @JesseJenkins, @ElephantEating @flexibledragnet, @leahstokes, @bataille_chris, @AlexRBarron, @jasonrwang, @drvox, @DrMarcHafstead, @KevinSLeahy.

Others whom we've talked with on this or may be interested: @JustinHGillis, @Ben_Inskeep, @croselund @RichardMeyerDC, @gilbeaq, @arthurhcyip, @bradplumer, @AdeleCMorris, @anunezjimenez, @mmehling, @DustinMulvaney, @RichardTol, @BorensteinS, @MichaelWWara, @BenJGarside.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter